Abstract

Undiagnosed retained placenta after vaginal delivery can result in significant hemorrhage, maternal morbidity, and even mortality. Several risk factors for retained placenta have been documented in the literature, including placenta accreta spectrum, previous history of uterine curettage, multiple gestations, preterm birth, velamentous insertion of placenta, poorly treated endometritis, multiparity, advanced maternal age, stillbirth, uterine anomalies, and Asherman syndrome. The occurrence of retained placenta and its associated complications, such as maternal morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage and endometritis is more common in developing countries due to a low ratio of trained obstetricians and midwives to the number of pregnant women.

Different society guidelines vary on the timing of intervention in cases of retained placenta, it is therefore imperative to evaluate and tailor the management approach to each case as needed. We present a case report of a multiparous woman with an unrecognized retained placenta who presented with unprovoked torrential bleeding nineteen months after delivery.

Keywords

Retained placenta, Retained products of conception, hemorrhage, hysterectomy

Introduction

Delayed placenta delivery can result in postpartum hemorrhage [1-3]. Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality globally and retained placenta accounts for nearly 20% of severe cases [3]. Unattended retained placenta is the second leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) [2].

A placenta is considered retained if it is not expelled within 30 minutes after the delivery of the fetus [3]. Normally, this expulsion is rapid [3], spontaneous in most (90%) cases [3], and even faster with routine protocol of active management of third stage labor [1-3]. Retained placenta occurs in 1-3% of vaginal deliveries [2,3] with significant postpartum hemorrhage occurring in approximately 1% [1].

Attempting manual removal of the placenta (MROP) is a standard recommendation where the placenta is not expelled within 30 min to 1 h after the fetal delivery [4,5]. However, risks associated with persistent placental tissue following a failed or incomplete removal include heavy bleeding, hysterectomy, increased morbidity, and mortality [1,2,6].

Ignoring placental delivery by active management of third stage of labor or failure of MROP is associated with risk of hemorrhage and infection [1,6]. Surgical intervention may be necessary to prevent hemorrhage and sepsis when placenta delivery fails, making conservative management a logical option in selected cases [1,2]. Although conservative management, allowing for spontaneous placental expulsion or resolution, has been reported as successful [1,2], its unpredictability specially in term pregnancies is still a matter of concern [1]. A success rate of 77% has been documented without surgical intervention. Placental expulsion, resorption, or removal has been shown to occur at a median of 3-4 months postpartum, with some cases persisting for up to a year [1,6].

The duration of disappearance may vary based on surveillance method used— MRI, ultrasound, hysteroscopy—as well as the duration of follow-up. Hysteroscopy is considered the most reliable method and has been documented in one case to detect retained placenta as long as 201 days postpartum [1]. Earlier gestation pregnancies tend to show a faster time to disappearance [1].

Retained placenta is generally seen in cases of uterine atony, abnormally adherent placenta —such as placenta accreta spectrum—or when the cervix closes before placental expulsion [2].

An unsuccessful attempt at manual removal of the placenta is common in cases of morbidly adherent placenta or placenta accreta spectrum, often resulting in postpartum hemorrhage [2,6,7].

Most complications of retained placenta were reported within the first 60 days postpartum in a case series [1]. Placental disappearance was faster when manual removal of placenta was done compared to cases where no attempt was made. The lower gestational age at delivery was associated with a shorter time to spontaneous disappearance of retained products of conception or placenta, as well as a more rapid decline in β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG). The rate of β-HCG decline may serve as a predictor of complication risk [1].

A follow up study of women with retained placental tissue revealed that all grades of bleeding were limited within 60 days postpartum. Human chorionic gonadotropin was also found to have dropped below the measurable threshold at a median of 67 days postpartum with an average of 23 to 113 [1].

Case

The patient was a 39-year-old female, Para 4 (4 alive) who was referred to our facility due to intractable massive vaginal bleeding lasting for two days. She had attended her antenatal care at a maternity home, where she had also delivered all her previous vaginal births. The last confinement was 19 months prior to presentation. Her pregnancy and labor were said to be uneventful. She had weaned her baby from breastfeeding at one year, however her menstrual cycle was yet to return. Two weeks prior to presentation, she visited a primary health care center with complaints of amenorrhea and abdominal fullness, At that time, her quantitative serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels were less than 5 international units. Other hormone profile results including luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), testosterone, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), were essentially normal. A pelvic ultrasound scan revealed a bulky uterus measuring 84 x 66 mm with a regular outline and homogenous myometrial echotexture, the endometrium was distended by a heterogenous mass with cystic changes, measuring 54 x 53 mm. No increase in internal or peripheral vascularity was observed with Doppler interrogation. She was subsequently referred to a secondary health facility for further assessment but had not attended her appointment before the onset of bleeding.

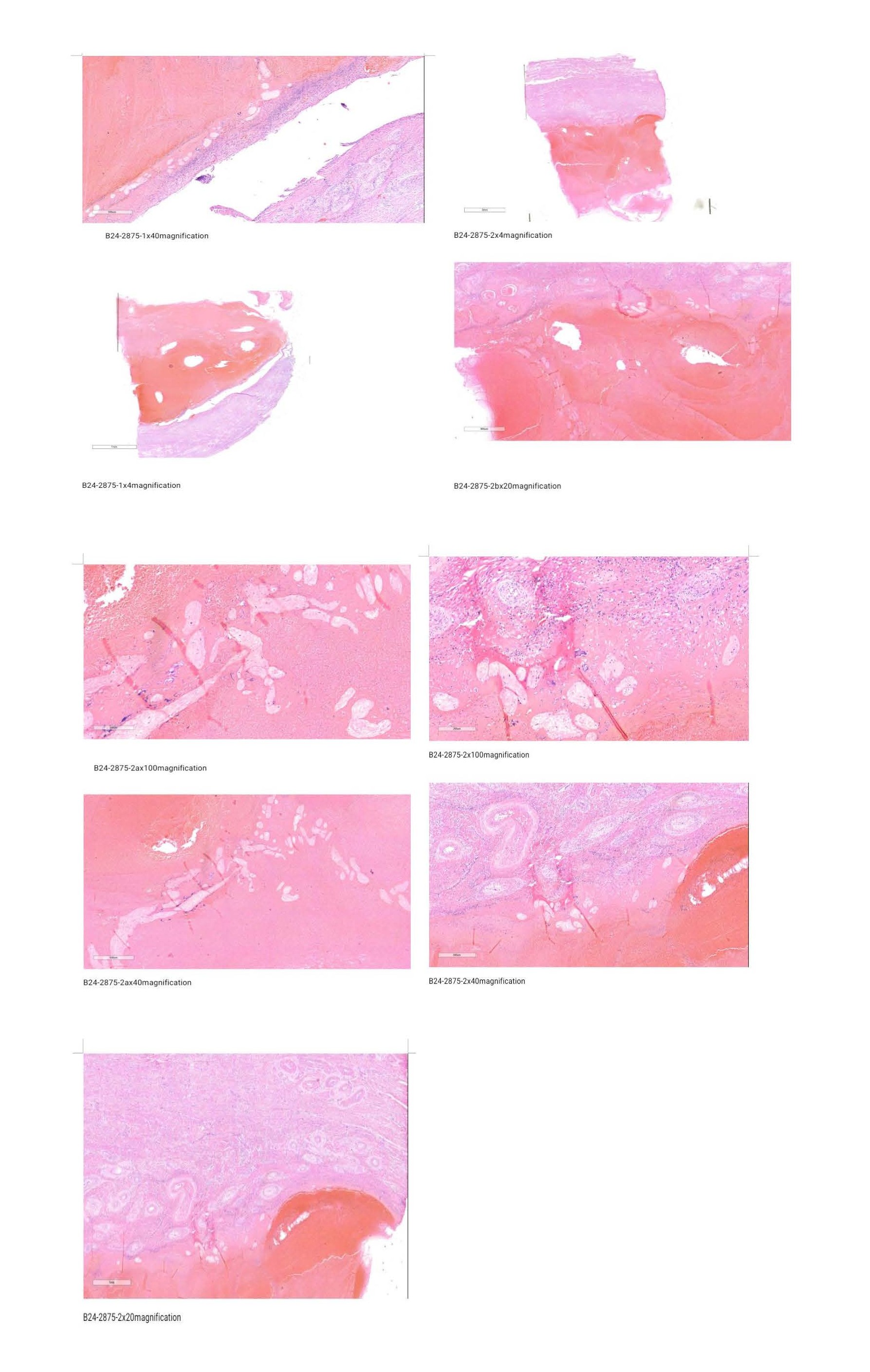

She was then brought to our facility with two days of torrential vaginal bleeding. Her vital signs on arrival were as follows: SO2 of 96%, Pulse rate 126 bpm, Respiratory rate 24 cycles per minute, BP- 90/50 mmHg. Her Packed cell volume was 20%. Her serum tumor markers on arrival showed: Ca-125 of 33.12 (0 – 35 U/ml), AFP 3.25(0 - 8 IU/ml), LDH 471.94 ↑ (225 - 450 IU/L). CEA 2.02 (5.0 - 8.5 ng/ml), B-HCG 1.58 (0 - 5 mIU/ml). She was resuscitated with intravenous crystalloid and blood transfusion. A Bedside pelvic ultrasound scan showed similar findings. Subsequently, she consented to a total abdominal hysterectomy, as she had completed her family size. Her post-operative recovery was satisfactory, and she was discharged on the third post-operative day with a packed cell volume of 31%. Histology revealed numerous degenerating chorionic villi lined by typical trophoblastic epithelium within a background of blood clot. The myometrium and fallopian tubes are unremarkable. Her histological findings were consistent with retained placental tissue.

Figure 1. Gross surface and cut section of the uterus, respectively.

Figure 2. Micrographs of histological sections of retained placental tissue within the uterus at different magnifications.

Discussion

Most authorities recommend manual removal of placenta if it remains undelivered after 30 minutes to 1 hour after delivery, with back up plans in place to manage potential hemorrhage if it occurs [4,5].

Risk factors for retained placenta parallel those for uterine atony and morbidly adherent placenta such as prolonged oxytocin use, high parity, preterm birth, prior uterine surgery, congenital uterine anomalies, conceptions by IVF, and a history of retained placenta [2].

Complications may include major hemorrhage, endometritis, or persistent placental tissue leading to delayed hemorrhage or infection [2].

Retained products of conception or placenta tissues typically appear as a heterogeneous intrauterine mass on ultrasound in the postpartum period [7]. Antenatal detection of placenta accreta spectrum is possible with ultrasound in 90% of cases [8], and accuracy improves with color Doppler [9,10]. The ante-natal diagnosis in the second or third trimester makes for anticipation and improved maternal outcomes by early activation of postpartum protocol [11]. MRI is more expensive and useful in the diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum [9,12].

The size of retained products of conception on ultrasound, blood flow on Doppler ultrasound, contrast enhanced CT, contrast-enhanced MRI are all not predicative of success of spontaneous disappearance [1].

Forced manual removal of the placenta, aimed at completely emptying the uterus, was more associated with postpartum hemorrhage than when not performed in asymptomatic cases [1,6]. In the setting of morbidly adherent placenta or placenta accreta spectrum, this approach should be avoided due to a higher risk of massive postpartum hemorrhage compared to caesarean hysterectomy [6], which is considered the standard in cases where future fertility is not needed, offering lower maternal morbidity. Alternatively, a fertility-preserving conservative approach may be considered [6]. The drawbacks of the conservative approach include the need for strict adherence to treatment and long-term postpartum follow-up. There remains a persistent risk of severe bleeding or infection for weeks or even months after delivery, with the possibility of interval or delayed hysterectomy occurring at a median of 22 weeks and in some cases up to 45 weeks postpartum [6].

Cesarean hysterectomy with the placenta in situ, especially in cases of morbidly adherent placenta or placenta previa, is typically more technically demanding than other elective cesarean hysterectomies, often resembling a modified radical hysterectomy. This complexity arises from the need for greater caution to maintain a safe margin from the vascular cervical-placental mass while simultaneously protecting the urinary system [13].

Delayed or interval hysteroscopic resection or morcellation of retained products of conception has been documented with complete resection in 90% of cases with fewer complications from perforation and intrauterine adhesion compared to blind curettage [14-16].

Medical treatment with methotrexate has also been used for retained products of conception in late pregnancy [6,17] but its effectiveness remains unproven. Methotrexate has been proposed as adjuvant treatment to improve the success rate of conservative treatment and hasten the postpartum involution of the placenta [6].

Conservative management alongside delayed or interval hysterectomy is now becoming more common [18-20] with careful patent selection and follow up due to risks of sepsis or hemorrhage requiring urgent hysterectomy [19].

In our case, acute severe hemorrhage warranted urgent definitive surgical intervention with delayed hysterectomy, as the patient had no desire for future fertility.

Conclusion

Retained placenta after vaginal delivery can result in significant hemorrhage and associated maternal morbidity. The practice of active management of the third stage of labor has reduced the likelihood of retained placenta or placenta tissues after vaginal delivery. Awareness of risk factors enables the implementation of preemptive measures to mitigate hemorrhage risk. Expectant, medical and surgical treatments are management options. Expectant, medical, and surgical treatments are management options. Surgical management by hysterectomy may be performed as a cesarean hysterectomy, interval hysterectomy, or delayed emergency hysterectomy, depending on the indication, particularly in cases of significant bleeding.

Disclaimer (Artificial Intelligence)

Author(s) hereby declares that NO generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc) and text-to-image generators have been used during writing or editing of manuscripts.

Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest declared.

References

2. Perlman NC, Carusi DA. Retained placenta after vaginal delivery: risk factors and management. Int J Womens Health. 2019 Oct 7;11:527-34.

3. Franke D, Zepf J, Burkhardt T, Stein P, Zimmermann R, Haslinger C. Retained placenta and postpartum hemorrhage; time is not everything. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;304(4):903-11.

4. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Intrapartum Care: Care of Healthy Women and Their Babies During Childbirth; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK): London, UK, 2014.

5. Oluwole AA, Omisakin SI, Ugwu AO. A Retrospective Audit of Placental Weight and Fetal Outcome at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Medicine and Health Development. 2024 Sep 18;29(4):305-9.

6. Sentilhes L, Ambroselli C, Kayem G, Provansal M, Fernandez H, Perrotin F, et al. Maternal outcome after conservative treatment of placenta accreta. Obstet. Gynecol.2010 Mar; 115(3): 526-34.

7. Mercier AM, Ramseyer AM, Morrison B, Pagan M, Magann EF, Phillips A. Secondary Postpartum Hemorrhage Due to Retaned Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Case Report. Int J Womens Health. 2022 Apr 22;14:593-7.

8. Jauniaux E, Bhide A. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and outcome of placenta previaaccreta after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jul; 217(1):27-36.

9. Ayati S, Leila L, Pezeshkirad M, SeilanianToosi F, Nekooei S, Shakeri MT, et al. Accuracy of color Doppler ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis of placenta accreta: a survey of 82 cases. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2017 Apr;15(4):225-30.

10. D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Nov;42(5):509-17.

11. Wong HS, Hutton J, Zuccollo J, Tait J, Pringle KC. The maternal outcome in placenta accreta: the significance of antenatal diagnosis and non-separation of placenta at delivery. N Z Med J. 2008 Jul 4;121(1277):30-8.

12. Tanaka YO, Shigemitsu S, Ichikawa Y, Sohda S, Yoshikawa` H, Itai Y. Postpartum MRI diagnosis of retained placenta accreta. EurRadiol. 2004 Jun;14(6):945-52.

13. Hoffman MS, Karlnoski RA, Mangar D, Whiteman VE, Zweibel BR, Lockhart JL, et al. Morbidity associated with nonemergent hysterectomy for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;202(6):628.e1-5.

14. Guarino A, Di Benedetto L, Assorgi C, Rocca A, Caserta D. Conservative and timely treatment in retained products of conception: a case report of placenta accreta retention. Int J ClinExpPathol. 2015 Oct 1;8(10):13625-9.

15. Lee MHM. Surgical management of retained placental tissue with the hysteroscopicmorcellation device. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019 Jan-Mar;8(1):33-5.

16. Hamerlynck TW, van Vliet HA, Beerens AS, Weyers S, Schoot BC. HysteroscopicMorcellationVersus Loop Resection for Removal of Placental Remnants: A Randomized Trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016 Nov-Dec;23(7):1172-80.

17. Dasari P, Venkatesan B, Thyagarajan C, Balan S. Expectant and medical management of placenta increta in a primiparous woman presenting with postpartum haemorrhage: The role of Imaging. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4(5):32-40.

18. Zuckerwise LC, Craig AM, Newton JM, Zhao S, Bennett KA, Crispens MA. Outcomes following a clinical algorithm allowing for delayed hysterectomy in the management of severe placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;222(2):179.e1–179.e9

19. Matsuzaki S, Grubbs BH, Matsuo K. Delayed hysterectomy versus continuing conservative management for placenta percreta: which is better? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Aug;223(2):304.

20. Collins SL, Sentilhes L, Chantraine F, Jauniaux E. Delayed hysterectomy: a laparotomy too far? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;222(2):101-2.