Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects 4% of individuals over 60 years old, an incidence rising to 9% in those over 80. For patients with symptomatic AF unresponsive to medication, catheter ablation is a common treatment, though it carries risks including cardiac tamponade, thromboembolic events, and rarely, atrio-esophageal fistula (AEF). AEF, a severe complication (up to 0.1%) with a mortality rate of 67%-100%, arises from thermal injury to the esophagus. Cardiac, neurologic or infection related symptoms appear 2 days to 6 weeks post-procedure. This report details a case of a patient who developed AEF following AF ablation. Initial symptoms included chest pain and nausea, which progressed to severe neurological deficits and septic shock. Diagnosis was confirmed by imaging, and the patient underwent urgent surgery to repair the fistula. Despite intensive care and surgical intervention, the patient faced significant complications, highlighting the critical need for early detection and prompt management of AEF.

Keywords

Atrio-esophageal fistula (AEF), Atrial fibrillation ablation, Radiofrequency ablation, Postablation complications, Left atrium, Esophageal perforation, Cardiac complications, Diagnosis and imaging in AEF

Abbreviations

AF: Atrial Fibrillation; AEF: Atrio-Esophageal Fistula; NYHA: New York Heart Association (Dyspnea scale evaluation); TEE: Transesophageal Echocardiography; BPM: Beats Per Minute; NSTEMI: Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; ECG: Electrocardiogram; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; AKIN: Acute Kidney Injury Network; CT: Computed Tomography; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; VA-ECMO: Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; ROSC: Return of Spontaneous Circulation; OGD: Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects approximately 4% of individuals over 60 years old and 6% of those over 80, significantly increasing the risk of thromboembolic cerebrovascular accidents and rhythm-related heart diseases [1]. For patients with symptomatic AF refractory to conventional pharmacological treatments, radiofrequency or cryotherapy ablation is a viable therapeutic option. While generally safe and effective, ablation carries risks such as cardiac tamponade (0.2-5%), thromboembolic events (2-15%), and peripheral vascular injuries (0.2-1.5%) [2]. Less common complications include phrenic nerve injury (0.08%), secondary pulmonary vein stenosis (0.05%), arrhythmias, and sudden death [11].

A rare but catastrophic complication is the development of an atrio-esophageal fistula (AEF), with an incidence of 0.03-0.1% and a mortality rate of 67-100% [3,4]. The proximity of the left atrium to the esophagus and thermal injuries from ablation facilitate AEF formation [5]. Symptoms are often nonspecific and can manifest between 2 days to 6 weeks post-procedure, including fever, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, melena, dysphagia, chest discomfort, seizures, altered consciousness, and hemiparesis.

Clinical Case

We present the case of a male patient in his sixties with a history of alcohol and tobacco use, controlled hypertension (nebivolol 5 mg and amlodipine 10 mg daily), and hypercholesterolemia (atorvastatin 40 mg daily). In late 2023, he developed heart failure, presenting with NYHA III dyspnea and palpitations. Hospital evaluation revealed new-onset atrial fibrillation, treated with successful electrical cardioversion after confirming the absence of intracardiac thrombi. Transthoracic echocardiography showed significant concentric left ventricular hypertrophy with an ejection fraction of 56% and atrial enlargement. The patient was prescribed anticoagulants (apixaban 5 mg twice daily) and antiarrhythmics (flecainide 150 mg daily) and was discharged after symptom resolution.

Five months later, the patient experienced persistent fatigue and a recurrence of atrial fibrillation (ventricular rate of 78 bpm) despite antiarrhythmic therapy. Radiofrequency ablation was proposed and performed under general anesthesia after confirming there was no thrombus in the left atrium via transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). A right femoral approach and TEE-guided transseptal puncture were used. Mapping enabled circumferential isolation of the pulmonary veins (posterior: 35W, Ablation Index 400; anterior: 40W, Ablation Index 450). Final TEE confirmed no abnormalities, and the patient maintained sinus rhythm. He was discharged without complications on continued antiarrhythmic (flecainide 150 mg daily), antihypertensive (amlodipine 10 mg, losartan 100/25 mg, nebivolol 5 mg daily), and anticoagulant therapy (apixaban 5 mg twice daily).

On the 24th day post-ablation, the patient presented to the emergency department with acute chest pain, radiating to the jaw, but without dyspnea. He also reported nausea, vomiting, holocranial headaches, and fever up to 38°C for several days. On examination, he appeared pale, with normal heart and lung sounds, a heart rate of 68 beats/min, blood pressure of 146/100 mmHg, oxygen saturation of 62%, respiratory rate of 15/min, and temperature of 37.1°C. Neurological examination was unremarkable (GCS 15/15). An ECG showed sinus rhythm at 68 beats/min. Blood tests revealed a rise in troponin from 13.8 to 54 ng/L, elevated D-dimer at 670 ng/mL, C-reactive protein at 23 mg/L, white blood cell count at 5.64 x 10^3/µL (86% neutrophils), and hemoglobin at 13.5 g/dL. A chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. The patient was admitted for the management of a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and pain control following the on-call cardiologist consultation.

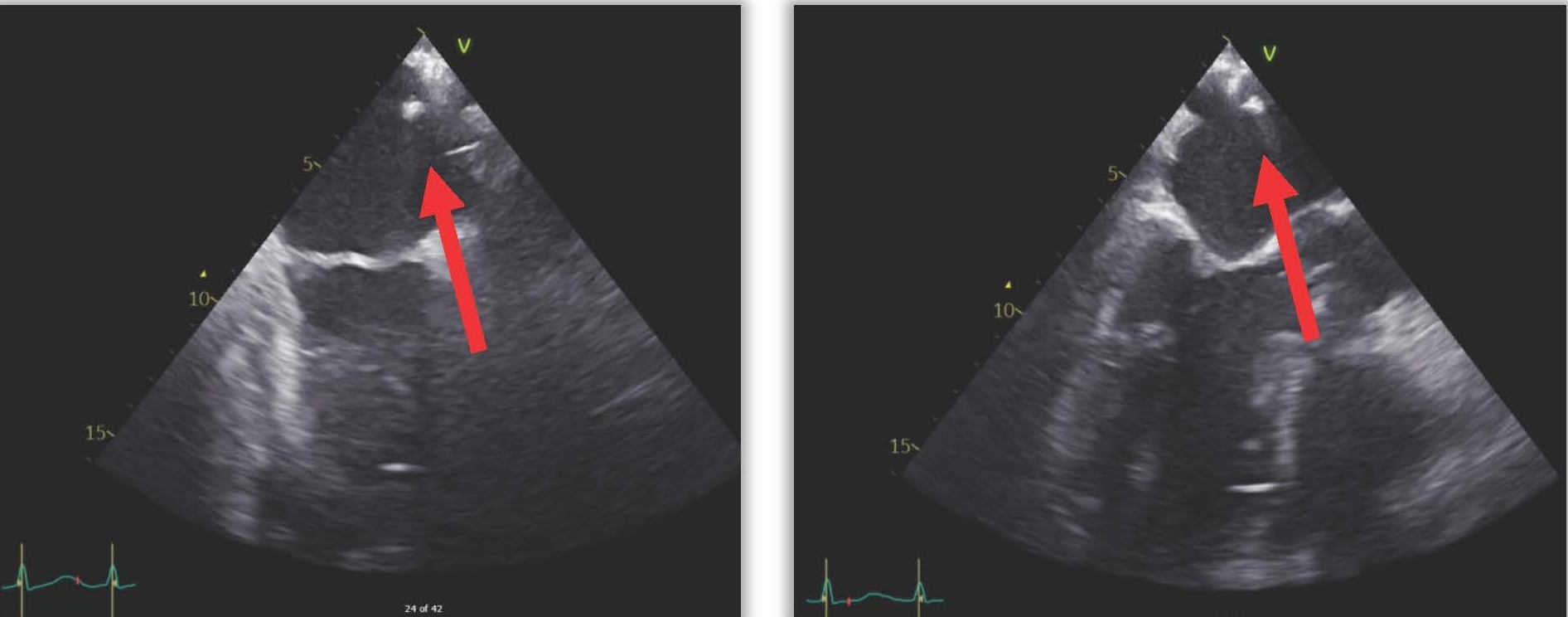

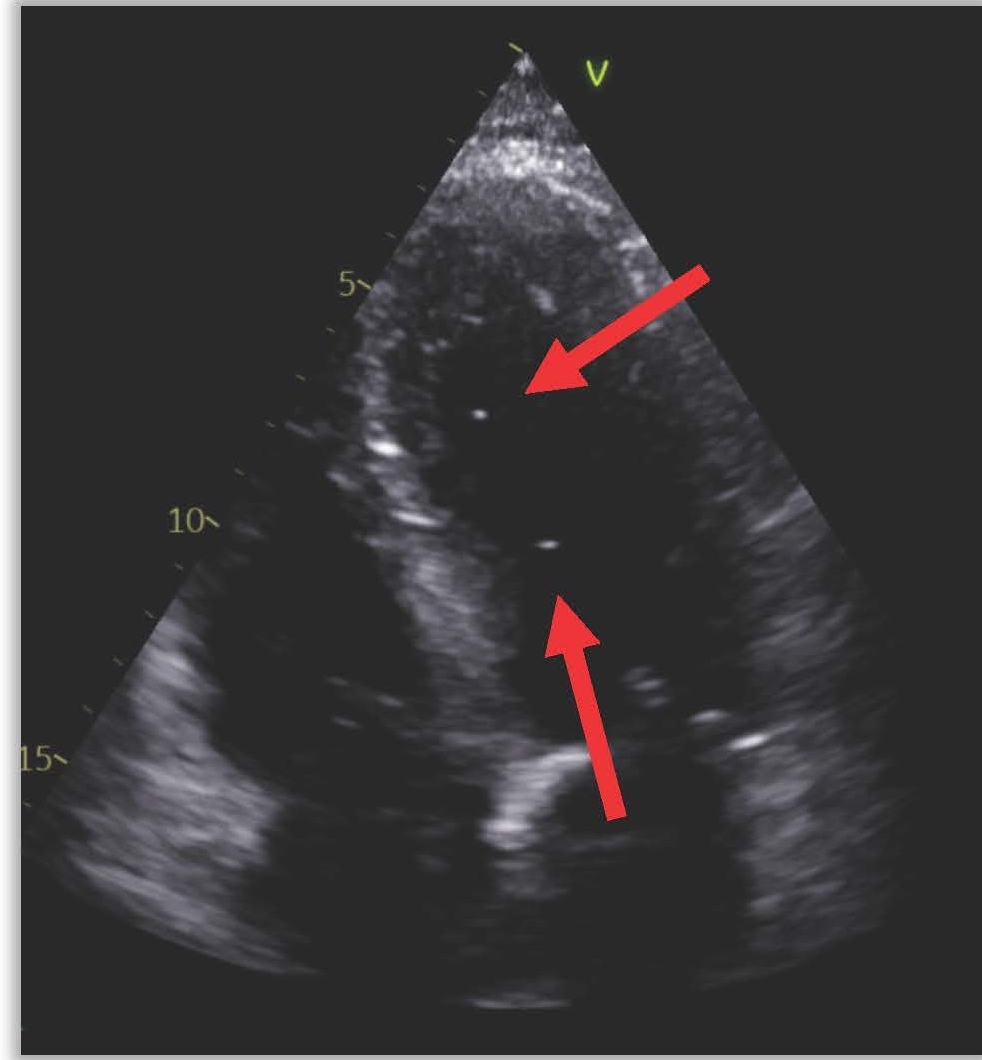

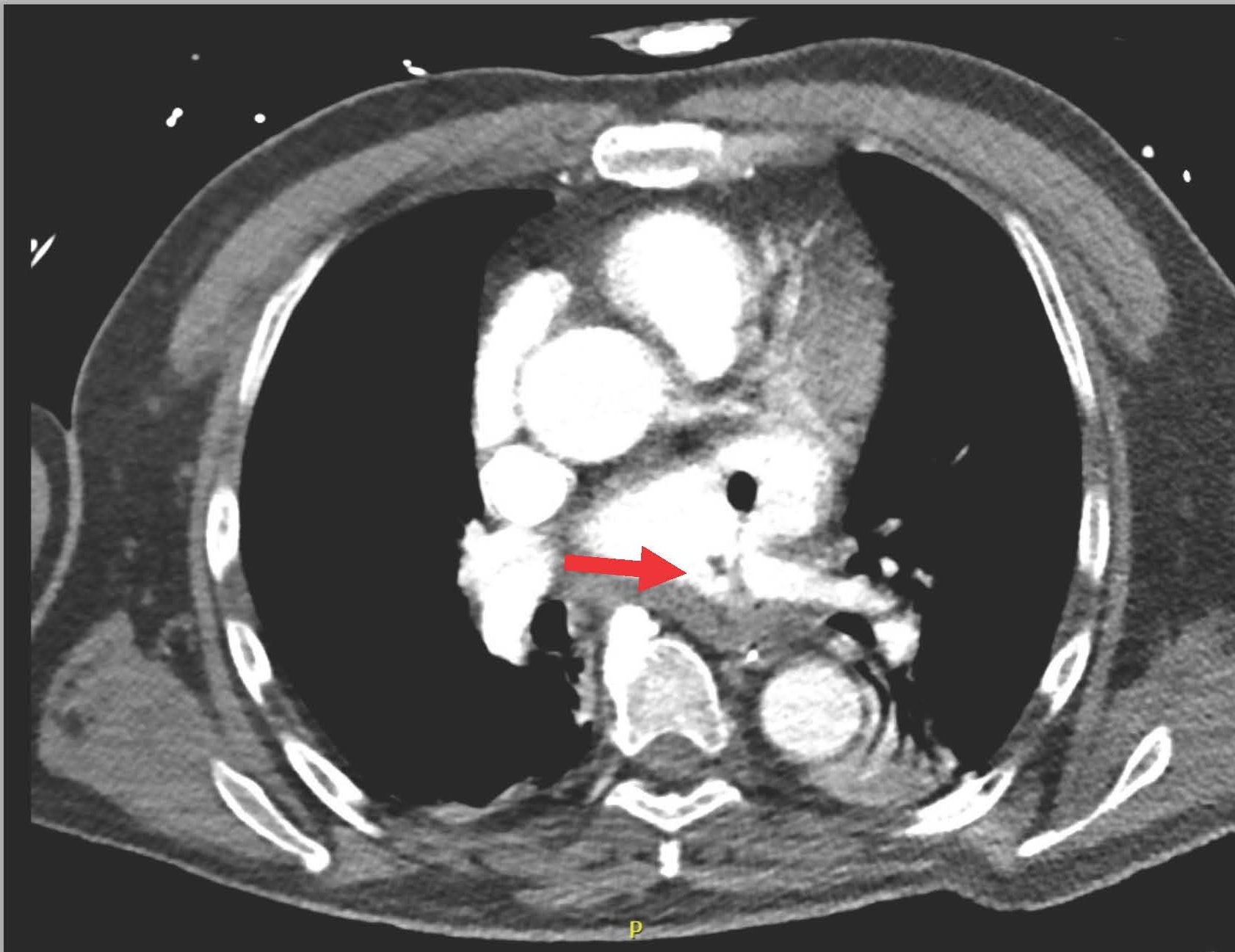

The next day (25 days post-ablation), the patient experienced significant neurological deterioration, with a GCS score dropping to 3/15, supraventricular tachycardia at 122 beats per minute, severe hypotension, and tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 36 per minute. A purpuric rash appeared on the neck, chest, and shoulders, and the patient was febrile with a temperature of 40°C. Due to the severe neurological and septic presentation, he was admitted to the ICU, intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation. Invasive monitoring and hemodynamic support were initiated. Blood tests showed a marked increase in C-reactive protein (210 mg/L), a white blood cell count of 7.16 x 10^3/µL (65% neutrophils), and significant renal function deterioration. First blood cultures identified multisensitive Streptococcus salivarius, leading to the initiation of antibiotic therapy with amikacin and ceftriaxone for suspected endocarditis. The lumbar puncture was sterile. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) later revealed a highly echogenic mass attached to the left pulmonary vein's ostium (Figure 1), severe left ventricular dysfunction, and air bubbles in cardiac cavities (Figure 2). A contrast-enhanced thoracic CT scan showed air in the left atrium and findings consistent with mediastinitis (Figure 3).

Figure 1. TEE showing an echogenic mass moving in the left atrium.

Figure 2. TEE showing air bubbles in intracardiac cavities.

Figure 3. Air present in the left atrium and communication between esophagus and LA.

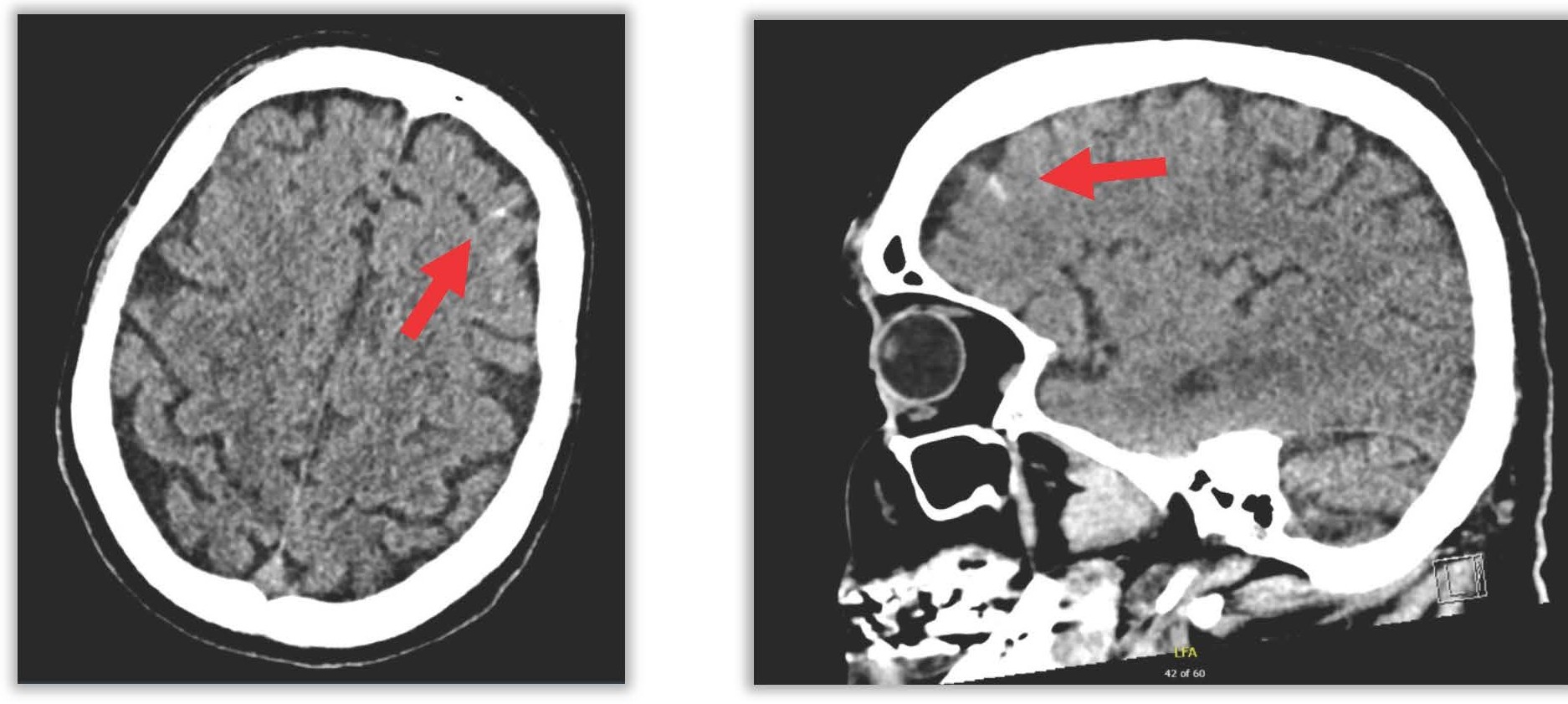

Multidisciplinary discussion led to the suspicion of an atrio-esophageal fistula. Cerebral imaging (CT) showed bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage in the frontal cortical sulci and hypodense frontal areas likely of ischemic origin (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Subarachnoid frontal hemorrhage.

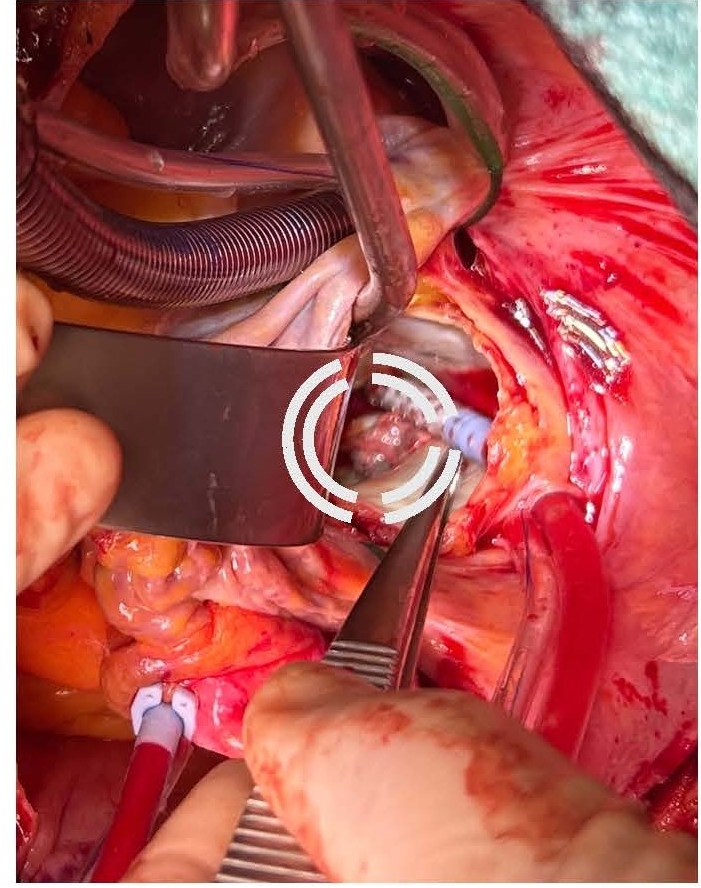

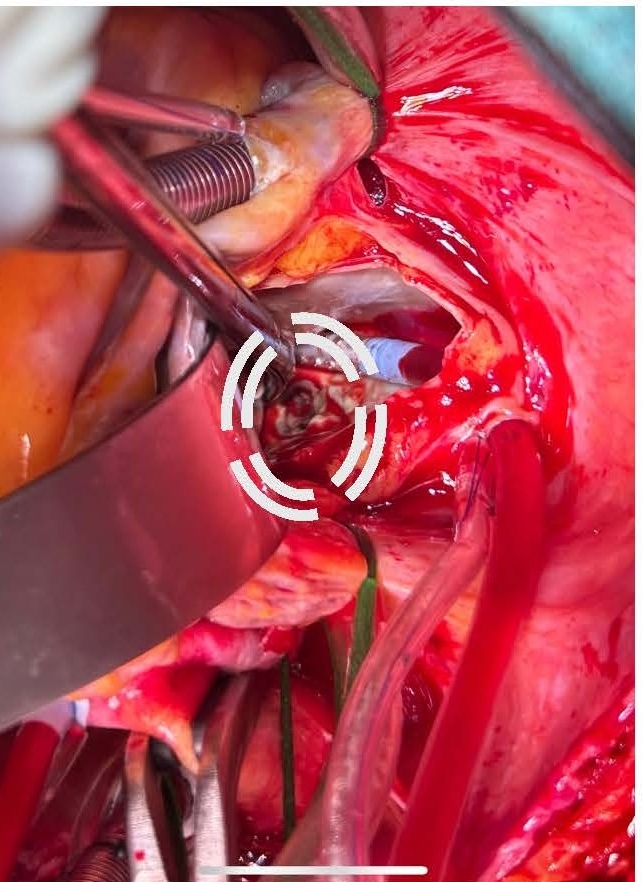

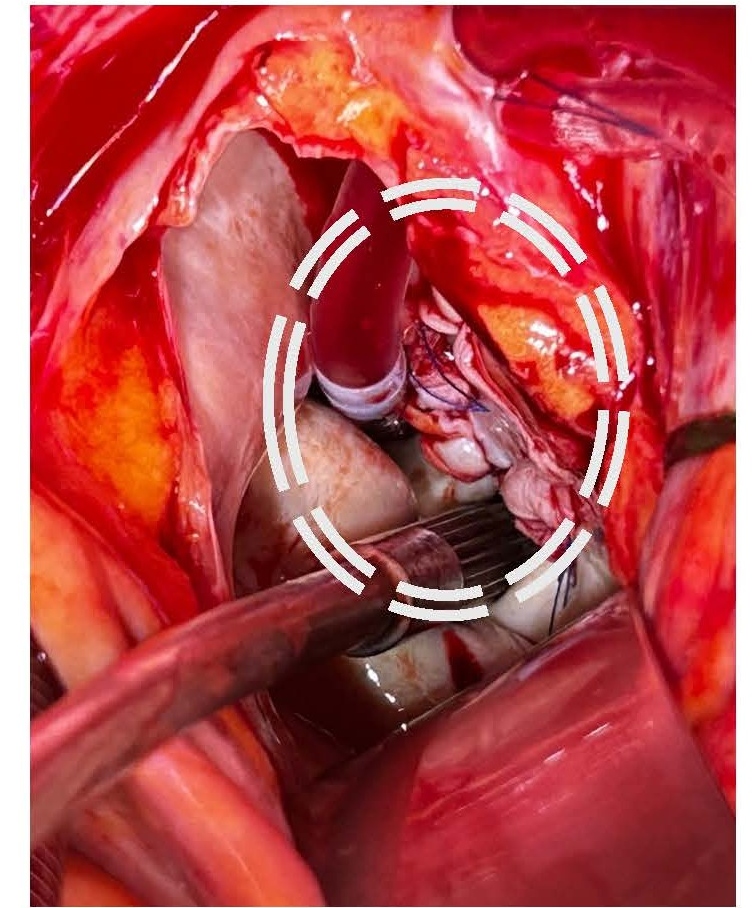

Given the severe clinical presentation, a decision was made to proceed with urgent cardiothoracic surgery on post-ablation day 26. Left atriotomy revealed a substantial vegetation associated with a necrotic fistulous orifice of approximately 1.5 cm in diameter located on the posterior wall of the left atrium near the left pulmonary vein ostia (Figures 5 and 6). The vegetation was resected, and purulent secretions were expressed from the fistulous orifice. Cultures of these samples later showed contamination with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus anginosus. The fistulous orifice was closed using an autologous pericardial patch (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Mass in the posterior wall of LA.

Figure 6. Fistula visible on the posterior wall of LA.

Figure 7. Repair of the fistula with pericardial patch.

Following atriotomy closure, a first aortic declamping was directly associated with massive esophageal bleeding, which was externalized through the patient's mouth. A second aortic clamping and a new atriotomy were performed to make a plication of the base of the left atrium to ensure the seal of the fistulous orifice. The second aortic declamping did not show any further esophageal bleeding. The aortic clamping and cardiopulmonary bypass times were 111 and 146 minutes, respectively. Cardiac conduction recovery was delayed, requiring the placement of ventricular pacemaker leads.

The immediate postoperative period was marked by severe cardiogenic and vasoplegic shock, which showed minimal response to vasopressors and inotropes, accompanied by a significant increase in lactate levels and a deterioration of LEVF to 15%. Due to clinical deterioration, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) was initiated in the intensive care unit for 7 days, followed by a gradual weaning from hemodynamic support. The complete resolution of septic shock allowed for the discontinuation of antibiotic therapy on postoperative day 36.

On post-ablation day 33, following hemodynamic stabilization, a bedside gastroscopy revealed a 2 cm esophageal perforation 30 cm from the dental arch. An esophageal stent was planned instead of clipping, but the procedure was complicated by severe hemodynamic instability and cardiac arrest. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved after 10 minutes. The esophageal stent placement was postponed. On post-ablation day 47, a follow-up endoscopy showed a persistently purulent orifice at the mid-esophagus, 26 cm from the dental arch. A fully covered esophageal stent (Boston Scientific Wallflex, 153 mm length, 25/18/23 mm diameter) was placed under radiographic guidance above the cardia, covering the fistulized area.

On post-ablation day 48, the patient's neurological status remained critical with a GCS score of 6/15 (E4V1M1). Brainstem reflexes were mostly absent, and the patient exhibited flaccid tetraplegia with diminished deep tendon reflexes and no pain response. MRI showed multiple ischemic lesions in both infratentorial and supratentorial regions, hemorrhagic transformation in the cerebellum, and signs of septic emboli. Following stabilization and several surgical interventions, transfer to a specialized coma unit was recommended.

Unfortunately, three days after the placement of the esophageal stent (on the 50th day post- atrial fibrillation ablation), the patient succumbed to a sudden cardiac arrest.

Pathophysiology and Recommendations

First described in 2004, atrio-esophageal fistula is a rare complication of atrial fibrillation catheter ablation, mainly caused by thermal injury from the ablation catheter. This can lead to non-conductive scar tissue and, when near the atrial posterior wall, esophageal mucosal damage. Esophageal lesions occur in 15-40% of patients [2], but fistula formation is very rare and not fully understood. Risk factors include esophageal motility disorders and impaired mucosal humidification. To reduce risk, proton pump inhibitors and esophageal temperature monitoring are recommended. In our center, during radiofrequency ablation, energy delivery is reduced on the posterior wall to minimize the risk of esophageal injury. On the “carto system”, a lower ablation index is targeted for the posterior wall compared to the anterior wall. In contrast, cryoablation does not require specific adjustments in energy application. A novel technique, pulsed-field ablation (PFA), has emerged as a potentially safer alternative. Due to its tissue-selective nature, PFA may significantly reduce the risk of this severe complication.

Symptoms typically develop 2 to 42 days post-procedure and include fever (83%), neurological deficits (51%), and hematemesis (36%). The clinical presentation can mimic infectious endocarditis, complicating diagnosis. Thoracic CT or MRI with contrast is the gold standard for detecting atrio-esophageal fistula (free air in the mediastinum or pericardium and a connection between the left atrium and esophagus with contrast extravasation through the fistula), while repeat imaging may be needed if initial results are negative. Transesophageal echocardiography and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be avoided until a fistula is ruled out to prevent massive air embolism [7].

There are no established guidelines for managing atrio-esophageal fistula, and without treatment, it is fatal. Mortality remains high even with surgery, ranging from 30-40% [6]. Surgical approaches vary based on the team's experience. Thoracotomy is preferred over sternotomy for better access and cardiopulmonary bypass [8]. Techniques include using an autologous pericardial patch and possibly a muscle flap between the left atrium and esophagus, along with esophageal prothesis placement. Although our technique differed, the latter is the one that has the better outcomes. Post-surgical morbidity and mortality are mainly due to sepsis from esophageal contents entering the left atrium and embolization of septic or air emboli to the brain [9].

Conclusion

The detection of atrio-esophageal fistula remains challenging due to its rarity, even for experienced cardiologists. However, with the increasing number of ablation procedures, the incidence of AEF cases is rising, underscoring the importance of heightened awareness of this complication. Given the severity of AEF, any delay in diagnosis can significantly compromise the patient's prognosis.

Therefore, it is imperative to suspect AEF in patients presenting with septic and/or neurological symptoms following atrial fibrillation ablation. Imaging serves as the primary diagnostic tool, and it is crucial to minimize esophageal manipulation through transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (OGD). Despite the high morbidity and mortality associated with it, surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of therapeutic management.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our gratitude to the cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery teams for their invaluable expertise and dedication in managing this complex clinical case. Special thanks are extended to the radiology department for their timely imaging support and to the intensive care unit staff for their relentless efforts in providing critical care.

We also acknowledge the contributions of the microbiology team in identifying the pathogens and guiding the antimicrobial therapy. Finally, we are deeply appreciative of the patient’s family for their trust and cooperation throughout this challenging journey.

This work underscores the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration in addressing rare and life-threatening complications, and we remain committed to advancing knowledge for better patient outcomes.

Author Contribution Statement

Dr Wilmet Nicolas: conceptualization, drafting the manuscript, data collection, and interpretation of clinical case details.

Drs Deladrière Hervé, Bidgoli Seyed Javad, Van Lerberghe Céline: supervision, review, and critical editing of the manuscript.

Dr Sanoussi Ahmed: surgical insights, review of operative techniques, and contributions to the discussion on management strategies.

All authors contributed to the design, development, and revision of this article and approved the final version for submission. Each author agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensures the integrity and accuracy of the information presented.

References

2. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017 Oct;14(10):e275-e444.

3. Dagres N, Anastasiou-Nana M. Prevention of atrial-esophageal fistula after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011 Jan;26(1):1-5.

4. Nair KK, Danon A, Valaparambil A, Koruth JS, Singh SM. Atrioesophageal Fistula: A Review. J Atr Fibrillation. 2015 Oct 31;8(3):1331.

5. Yang E, Ipek EG, Balouch M, Mints Y, Chrispin J, Marine JE, et al. Factors impacting complication rates for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation from 2003 to 2015. Europace. 2017 Feb 1;19(2):241-49.

6. Yousuf T, Keshmiri H, Bulwa Z, Kramer J, Sharjeel Arshad HM, Issa R, et al. Management of Atrio-Esophageal Fistula Following Left Atrial Ablation. Cardiol Res. 2016 Feb;7(1):36-45.

7. Siegel MO, Parenti DM, Simon GL. Atrial-esophageal fistula after atrial radiofrequency catheter ablation. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jul 1;51(1):73-6.

8. Al-Alao B, Pickens A, Lattouf O. Atrio-oesophageal fistula: dismal outcome of a rare complication with no common solution. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016 Dec;23(6):949-56.

9. Garala K, Gunarathne A, Jarvis M, Stafford P. Left atrial-oesophageal fistula: a very rare, potentially fatal complication of radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Nov 20;2013:bcr2013201559.

10. Evrard E, Gusu D, Hausman P, Glorieux D. Fistule atrio-oesophagienne post ablation par radiofr�quence: une complication rare et souvent fatale. www. louvainmedical. be. 2018 Dec:702-7.

11. Benali K, Khairy P, Hammache N, Petzl A, Da Costa A, Verma A, et al. Procedure-Related Complications of Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 May 30;81(21):2089-99.