Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease which causes joint pain, swelling and destruction, leading to reduced quality of life and premature death. The treatment of RA has progressed significantly in recent decades. However, non-adherence is a crucial yet underestimated barrier to optimal therapeutic success. This minireview gives a brief overview of the state of knowledge on adherence.

Introduction

In the last decades there has been considerable progress in treatment, significantly improving quality of life, outcome and prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1]. Therapy adherence is a cornerstone of improved outcome [2,3]. However, recent studies have shown that adherence may be low in a considerable percentage of patients [4,5]. There are multiple factors influencing adherence such as the relationship between physician and patient, socioeconomic and demographic factors, the patient’s cognitions, perceptions of the disease, health literacy and the medication itself, including route of application, polypharmacy and side effects [3,6,7]. This minireview presents a short summary of terms, definitions, methods and data concerning current research of adherence in RA with the aim of increasing the awareness of this topic.

Methods

PubMed was searched using the terms “adherence” and “rheumatoid arthritis”. We included both reviews and primary research articles published in English between 1997 and 2020. The article selection was based on our subjective impression of importance. The included publications were neither formally assessed nor rated.

Terms and definitions

Adherence versus Compliance: The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior, taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.”[8]. Although often used synonymously, the term “compliance” is negatively connotated for implicitly judging the patient’s behavior. While compliance refers to the patient following the physician’s guidance, adherence includes shared decision making (SDM) with both the health care provider (hcp) and the patient explicitly agreeing on the choice of therapeutic options. Therefore, the term “adherence” values the patient as an active and responsible partner [8] and is to be preferred over the older term “compliance”.

Medication adherence may be divided into three main components, initiation adherence (the patient starting the medication), execution adherence (the patient responsibly taking the medication) and persistence (the period of time the patient continuously takes the medication) [9].

Concordance: The concept of “concordance” implies adherence based on the equality of the physician-patient partnership with the patient’s views and knowledge of the disease fully incorporated into the SDM process leading to concordance of the patient’s and the hcp’s views and aims.

Non-adherence: Not following the mutually agreed upon recommendations is referred to as “non-adherence”. Intentional non-adherence (INA) is defined as the patient actively deciding not to follow the recommendations, e. g. the patient weighs perceived risks against possible benefits and actively decides against the recommended therapy [10]. INA must be differentiated from unintentional non-adherence such as misunderstanding of the hcp’s recommendations or the patient unintentionally forgets to take the medicine.

Although there is no specific cut-off separating adherence from non-adherence, taking 80% of the medication is the frequently used definition of adherence in current literature. However, this cut-off is arbitrary and not supported by data showing clinical significance [6].

Methods of measuring adherence

An abundance of methods has been developed to measure adherence with significant variability in terms of their respective objectivity (the results not being biased by the patient’s or the hcp’s notion of social acceptability), reliability (providing stable and reproducible results) and their validity (correctly measuring medication adherence without influencing the patient’s behavior or being prone to manipulation). Feasibility is important as well: The ideal methods should be simple, cost-efficient, not harmful and invisible to the patient. Currently, there is no accepted gold standard for measuring adherence, complicating the comparison between different studies [4].

Direct measurements such as drug metabolite or biomarker assays [11] and indirect measurements such as pill counting, pharmacy refills [4], physical medication monitoring by the electronic Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS®) [12], self-reported adherence, adherence rated by the hcp [3,13] and adherence questionnaires are being used [4,14]. (Table 1) gives an overview of the different methods used to measure adherence and their pros and cons, respectively.

|

Assessment category |

Assessment method |

Pros |

Cons |

|

Direct measurement |

Drug monitoring, biomarker assays |

- objective - reliable

|

- expensive - invasive - Patient realizes surveillance leading to white-coat compliance [15] |

|

Indirect measurement: Medication monitoring |

Pill count, Prescription refills monitoring |

- easy - inexpensive - not visible to the patient |

- actual ingestion of medication not guaranteed |

|

MEMS® |

- objective |

- Patient realizes surveillance - expensive and intricate |

|

|

Self-reported |

- easy - inexpensive |

- unreliable - Patient realizes surveillance |

|

|

Questionnaires |

CQR-19/CQR-5

|

- easy - inexpensive - reasonable reliability and validity - validated specifically for RA |

- Patient realizes surveillance - Reliability and validity based solely on patients’ answers |

|

MMAS-4® |

- easy - inexpensive - reasonable reliability and validity |

||

|

MARS |

Therapy adherence rates in RA

There is considerable data concerning the extent of adherence in RA. In general, the results vary significantly depending on the type of medication, the patient cohort analyzed and the methods used to measure adherence, respectively.

Pasma et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 18 studies analyzing medication adherence in patients with RA. The medication monitored varied in the different studies, including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) such as methotrexate (MTX) or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and studies which did not specify the medication, respectively. Overall adherence rates varied considerably, encompassing a range of 49.5-98.5% [6]. The authors pointed out that despite many different assessment methods for adherence none of the studies combined different methods making interstudy comparisons difficult.

Another meta-analysis of 16 studies in DMARD/NSAID-adherence in RA by van den Bemt et al. showed an overall adherence of 22% (underuse) up to 107% (overuse) [4]. Again, the great variance in adherence ratios was attributed to the different assessment methods. For illustration, MEMS®-assessed rates ranged from 72% to 107% whereas reported pharmacy refills ranged between 22-73%. The authors pointed out that adherence is not a stable variable and may change over time [4]. Findings in a longitudinal study on MTX adherence underline this notion, demonstrating a decline in adherence with increasing disease duration and low to moderate disease activity [16].

Newer studies confirm this considerable variability in adherence, encompassing a wide range of results, e. g. correct DMARD-dosing (based on CQR and 80% adherence) in as few as 3.8% of the patients [17], high adherence rates (based on a MMAS®-score = 4) of 57.3% - 76.3% [18] up to correct dosing in two thirds of RA patients using MEMS®-technology [2] or high overall adherence in 80% of RA-patients (determined by proportion of days covered values > 0.8) [19].

Consequences of low therapy adherence

It is estimated that in general non-adherence inflicted an annual damage of $100 billion in the US [20]. As shown above, non-adherence is a common phenomenon, jeopardizing therapy efforts and leading to inferior disease control in RA [21], i.e. higher DAS28-score, adverse radiographic outcome and reduced quality of life [2,3].

Factors influencing adherence – dimensions of non-adherence as defined by the WHO

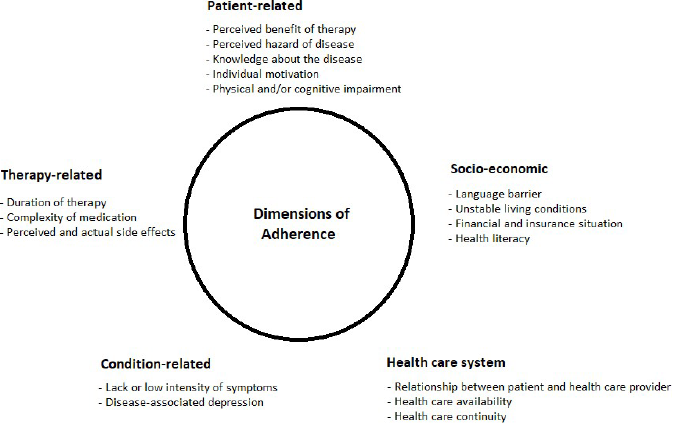

Recent reviews have shown only small effects and inconsistent findings for currently practiced interventions to improve adherence. This concerns both, chronic diseases in general and RA, in particular [22,23]. Identifying risk factors for non-adherence provides valuable information how to possibly improve adherence. While there are many different individual reasons for patients not taking their medication, the WHO currently defines five dimensions of non-adherence [8] displayed in (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The five dimensions of non-adherence [8], (modified by the authors).

The following paragraphs summarize current evidence in RA as related to the five dimensions of non-adherence.

Patient-related: There is strong evidence that one of the most important factors influencing adherence in RA patients is the perceived need to take the medication. Patients tend to weigh perceived risks of the therapy against the benefits, potentially resulting in intentional non-adherence. This is especially true when the disease activity is low or when therapy is perceived to be ineffective. The decision of taking the medication is based on the patient’s self-efficacy, knowledge of the disease and treatment-related beliefs [4,6,16,24]. For instance, the recent large scale multicenter study ALIGN, analyzing treatment-related beliefs and adherence in patients with RA, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, reported the perceived treatment necessity dominated concerns about medication and was associated with higher medication adherence [25,26].

Socio-economic: The current data on socioeconomic effects on adherence is very scarce and none of the factors such as gender, cultural aspects, tobacco use, economic status etc. have yet unequivocally been proven to influence adherence in a predictable manner [4]. However, poor health literacy has been shown to have a negative impact on adherence, emphasizing the importance of adequate patient empowerment [3,27].

Health care system: Improved communication between patient and hcp is positively associated with adherence. The patient’s trust in their hcp reduces intentional non-adherence [4,28].

Condition-related: While factors such as disease activity, functional status and perceived quality of life have been studied, no significant reproducible association with adherence has yet been reported [4]. However, better mental health status has been postulated to have a positive impact on adherence [2].

Therapy-related: The total amount of prescriptions per person in RA is constantly rising [29]. However, there is evidence that the number of medications needed to be taken has a negative impact on adherence [30]. For example, simplifying prescriptions has been shown to be the most effective single intervention to reduce non-adherence in patients with high blood pressure [31]. Furthermore, longer treatment duration has a negative impact on adherence [25].

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies to improve adherence in RA have been performed which are briefly summarized in (Table 2). In general, the improvement of adherence was low to moderate.

|

Study |

Study cohort and design, duration, number of patients, adherence measurement |

Intervention, related to the WHO-dimensions of adherence |

Results |

|

[32] |

RA Longitudinal cohort study, 6 months 732 patients PDC |

Patient-related: Educational vs. usual care |

Mean PDC was 89% (IG) compared to 60% (CG) (p<0.001) |

|

[33] |

RA and other chronic diseases RCT, 1 month 379 patients Self-reported adherence |

Patient-related: Educational vs. usual care |

91% (IG) adherent compared to 84% (CG) (p=0.032) |

|

[34] |

RA RCT, 6 months 122 patients MMAS-8® |

Patient-related: Educational vs. usual care |

98% (IG) adherent compared to 83% (CG) (p=0.0003) |

|

[35] |

RA RCT, 6 months 91 patients Biomarker Assay |

Patient-related: Educational vs. usual care |

85% of the IG were taking their medication as prescribed compared to 55% in the CG (p<0.05) |

|

[36] |

RA Prospective cohort study 201 patients CQR |

Patient-related: Behavioral |

Positive association between use of medication reminders and adherence |

|

[37] |

RA, Psoriatic arthritis and chronic inflammatory bowel diseases Cohort study, 6 months 306 patients MMAS-4® |

Therapy-related: Shared decision making vs. usual care |

Mean MMAS-4 was 0.41 in CG vs 0.17 in IG (p=0.001) |

|

[38] |

RA RCT, 12 months 59 patients Self-reported adherence |

Condition-related: Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. usual care |

Increase in medication adherence in IG at end of study compared to baseline, p<0.05 |

Discussion and Limitations

This minireview presents our subjective choice of articles pertinent to adherence in RA and thus may be prone to selection bias. The aim of this minireview is to acquaint the reader with important definitions, methods and data in this field to increase awareness of this clinically important matter. Adherence in RA – although being decisive for the therapeutic success - is often very low, thus impeding the potential therapeutic success with modern DMARDs. Although the relevant dimensions influencing adherence are known, data from RCTs how to significantly improve adherence in RA is still very scarce. In our opinion, the field for future research should encompass studies evaluating and comparing several methods of measuring adherence simultaneously in order to define a feasible gold-standard of adherence measurement. Interventional RCTs should systematically analyze factors related to adherence, amongst which shared decision making and empowerment of the patient might be – in our opinion – the most important and promising approaches.

Conclusion

In summary, non-adherence is frequent in RA-patients and therefore an important challenge in clinical practice. Patient-related factors as well as simplified treatment modalities seem to be promising targets to improve adherence. Empowerment of the patient leading to improved understanding of risks and benefits of treatment in a shared-decision-making process based on the patient’s trust in the hcp will probably be the most efficient way to improve adherence. In our opinion, interventional RCTs to reduce non-adherence are urgently needed.

Author Contributions

TR and JGK contributed equally to the preparation of this article. Both designed the article, selected the content and literature to be reviewed, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We thank John L. Crum, M.D. for carefully reading and revising our manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

JGK reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB. TR reports grants from Chugai and Novartis.

References

2. Waimann CA, Marengo MF, Achaval S de, Cox VL, Garcia‐Gonzalez A, Reveille JD, et al. Electronic Monitoring of Oral Therapies in Ethnically Diverse and Economically Disadvantaged Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: Consequences of Low Adherence. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(6):1421–9.

3. Kuipers JG, Koller M, Zeman F, Müller K, Rüffer JU. Adherence and health literacy as related to outcome of patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis : Analyses of a large-scale observational study. Z Rheumatol. 2019 Feb;78(1):74–81.

4. van den Bemt BJF, Zwikker HE, van den Ende CHM. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012 May;8(4):337–51.

5. Murage MJ, Tongbram V, Feldman SR, Malatestinic WN, Larmore CJ, Muram TM, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018 Aug 21;12:1483–503.

6. Pasma A, van’t Spijker A, Hazes JMW, Busschbach JJV, Luime JJ. Factors associated with adherence to pharmaceutical treatment for rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Aug;43(1):18–28.

7. van der Vaart R, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Drossaers-Bakker KW, Vonkeman HE, van de Laar MAFJ. Impact of patient-accessible electronic medical records in rheumatology: use, satisfaction and effects on empowerment among patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014 Mar 26;15:102.

8. Sabaté E, World Health Organization, editors. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. 198 p.

9. Dartsch D, Lim S, Schmidt C. Medikationsmanagement: Anleitung für die Apothekenpraxis. Govi-Verlag; 2015. 223 p.

10. Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999 Dec;47(6):555–67.

11. Bluett J, Riba-Garcia I, Verstappen SMM, Wendling T, Ogungbenro K, Unwin RD, et al. Development and validation of a methotrexate adherence assay. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(9):1192–7.

12. Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Methods for measuring, enhancing, and accounting for medication adherence in clinical trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jun;95(6):617–26.

13. El Alili M, Vrijens B, Demonceau J, Evers SM, Hiligsmann M. A scoping review of studies comparing the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) with alternative methods for measuring medication adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(1):268–79.

14. de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. The compliance-questionnaire-rheumatology compared with electronic medication event monitoring: a validation study. J Rheumatol. 2003 Nov;30(11):2469–75.

15. Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance Declines Between Clinic Visits. Arch Intern Med. 1990 Jul 1;150(7):1509–10.

16. de Thurah A, Nørgaard M, Johansen MB, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Methotrexate compliance among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the influence of disease activity, disease duration, and co-morbidity in a 10-year longitudinal study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010 May;39(3):197–205.

17. Rauscher V, Englbrecht M, van der Heijde D, Schett G, Hueber AJ. High degree of nonadherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;42(3):386–90.

18. Smolen JS, Gladman D, McNeil HP, Mease PJ, Sieper J, Hojnik M, et al. Predicting adherence to therapy in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis: a large cross-sectional study. RMD Open. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):e000585.

19. Berger N, Peter M, DeClercq J, Choi L, Zuckerman AD. Rheumatoid arthritis medication adherence in a health system specialty pharmacy. Am J Manag Care. 2020 Dec 1;26(12):e380–7.

20. Lewis A. Noncompliance: a $100 billion problem. Remington Rep. 1997;5(4):14–5.

21. Contreras-Yáñez I, Ponce De León S, Cabiedes J, Rull-Gabayet M, Pascual-Ramos V. Inadequate therapy behavior is associated to disease flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have achieved remission with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Am J Med Sci. 2010 Oct;340(4):282–90.

22. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Nov 20;(11):CD000011.

23. Galo JS, Mehat P, Rai SK, Avina-Zubieta A, De Vera MA. What are the effects of medication adherence interventions in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Apr;75(4):667–73.

24. Zwikker HE, van Dulmen S, den Broeder AA, van den Bemt BJ, van den Ende CH. Perceived need to take medication is associated with medication non-adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1635–45.

25. Michetti P, Weinman J, Mrowietz U, Smolen J, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Louis E, et al. Impact of Treatment-Related Beliefs on Medication Adherence in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases: Results of the Global ALIGN Study. Adv Ther. 2017;34(1):91–108.

26. Putrik P, Ramiro S, Hifinger M, Keszei AP, Hmamouchi I, Dougados M, et al. In wealthier countries, patients perceive worse impact of the disease although they have lower objectively assessed disease activity: results from the cross-sectional COMORA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Apr;75(4):715–20.

27. Joplin S, van der Zwan R, Joshua F, Wong PKK. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of patient education, health literacy, and musculoskeletal ultrasound. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:150658.

28. Pasma A, van ’t Spijker A, Luime JJ, Walter MJM, Busschbach JJV, Hazes JMW. Facilitators and barriers to adherence in the initiation phase of Disease-modifying Antirheumatic Drug (DMARD) use in patients with arthritis who recently started their first DMARD treatment. J Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;42(3):379–85.

29. Ziegler S, Huscher D, Karberg K, Krause A, Wassenberg S, Zink A. Trends in treatment and outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis in Germany 1997-2007: results from the National Database of the German Collaborative Arthritis Centres. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Oct;69(10):1803–8.

30. DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Reynolds M, Ogale S, Best JH. Assessing Methotrexate Adherence in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2015 Jun;2(1):73–84.

31. Matthes J, Albus C. Improving adherence with medication: a selective literature review based on the example of hypertension treatment. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int. 2014 Jan 24;111(4):41–7.

32. Stockl KM, Shin JS, Lew HC, Zakharyan A, Harada ASM, Solow BK, et al. Outcomes of a Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Therapy Management Program Focusing on Medication Adherence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010 Oct 1;16(8):593–604.

33. Clifford S, Barber N, Elliott R, Hartley E, Horne R. Patient-centred advice is effective in improving adherenceto medicines. Pharm World Sci. 2006 Sep 27;28(3):165.

34. Ravindran V, Jadhav R. The Effect of Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Education on Adherence to Medications and Followup in Kerala, India. J Rheumatol. 2013 Aug 1;40(8):1460–1.

35. Hill J, Bird H, Johnson S. Effect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001 Sep;60(9):869–75.

36. Bruera S, Lopez-Olivo MA, Barbo A, Suarez-Almazor ME. Use of Medication Reminders in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Value Health. 2014 Nov 1;17(7):A384.

37. Lofland JH, Johnson PT, Ingham MP, Rosemas SC, White JC, Ellis L. Shared decision-making for biologic treatment of autoimmune disease: influence on adherence, persistence, satisfaction, and health care costs. Vol. 11, Patient Preference and Adherence. Dove Press; 2017. p. 947–58.

38. Evers AWM, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PLCM, de Jong AJL. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. PAIN. 2002 Nov;100(1):141–53