Abstract

Examination of the surface of bones (from which soft tissues have been removed) provides a window complementary to that provided by clinical, standard anatomic, laboratory and radiologic studies. That approach, utilized successfully for analysis of other forms of osteosarcoma is applied to the high grade telangiectatic version of medullary osteosarcoma. Examining the surface of afflicted bones overcomes the limited resolution of standard radiologic techniques Herein, the character of bone surface of the telangiectatic variety, previously only theorized in a skeleton from an archeologic sites and subject to isolated veterinary reports, is categorized in an individual with documented disease.

A previously healthy 29 year old Swiss Caucasian male presented with swelling at the lateral aspect of the leg, just proximal to the ankle. Radiological examination revealed cortical breakthrough and slight focal periosteal reaction, associated with severe cortical thinning and an irregular medullary region with subtle cystic areas. This contrasts with other forms of osteosarcoma which grow around residual cortex rather than producing a thin rim.

Keywords

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma, Surface anatomy, Periosteal reaction

Introduction

Four basic windows have provided our insights into the nature and character of osteosarcomas: Clinical, anatomic, laboratory, and radiologic. What effect does it have on the afflicted individual? What changes does it induce in “host’s” anatomy? Why does it occur (environmental and genetic factors)? How does the host respond (metabolic, hematologic, immunologic and chemical responses) and how does it alter the “host’s” appearance when viewed by the expanded radiologic study options? Additional insights derive from study of its history, not the experience of a single individual or clinical population, but as a historical phenomenon.

Artificially-prepared mummies provide one such option for such study. Mummification was a practiced procedure utilized throughout much of the ancient world, especially in some cultures (e.g., Egyptian and Chinchorro). Natural mummies additionally afford an opportunity to examine internal organs, so often removed in artificial mummification processes. Disorders affecting the musculoskeletal system still remain accessible for study. That is fortunate, as so much of neoplasia identification is now predicated upon immunologic and genetic (DNA) analysis of associated soft tissues [1]. Beyond the Holocene (past ~10,000 years), mummies are quite rare [2]. The soft tissues seem rarely preserved, so analysis is limited to what can be discerned from actual physical examination of the preserved bones. That is fortunate for study of bone tumors, as radiologic studies (of individuals in whom neoplasia is suspected) can be compared to those in modern individuals afflicted with the same diseases [3,4]. That option offers a unique opportunity, allowing observation of actual bone damage. Examining the surface of afflicted bones overcomes the limited resolution of standard radiologic techniques (e.g., 0.3 mm for high resolution x-rays; 0.6 mm for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [5]. It permits identification of previously unrecognized disease manifestations, such identification providing insights applicable to clinical disease recognition and management (e.g., myeloma character) [3,6].

The limited amenability of fossil and sub-fossil soft tissues to histologic study is not actually disadvantageous to recognition of neoplasia. We understand that skeletal pathologists will not report an osteosarcoma diagnosis without examining the radiologic studies, because the histology often does not permit distinguishing osteosarcoma and osteomyelitis [7]. Thus, the radiologic appearance allows recognition of osteosarcomas and distinguishing among the varieties. At least, that has been the case until more recent variety subdivisions predicated on recognition of specific immunologic soft tissue (neoplastic cell) markers. As these are seemingly not preserved in the sub-fossil and fossil record, further discussion will be limited to identification of occurrence and antiquity of the originally described forms of osteosarcoma. These include parosteal, periosteal, and medullary or central and its high grade variant, telangiectatic [8].

The manifestations of medullary, parosteal and periosteal osteosarcomas, observable on bones (when soft tissues are no longer present), have been well documented [9,10]. The appearance of bones affected by the telangiectatic form of osteosarcoma responsible for 2-12% of human osteosarcomas [11] has been suggested in a dog from the 3rd-5th century CE [12], and reported as isolated cases in rhesus macaca [13], dog [14], cat [15] and horse [16], but not documented in human, until now. Also referred to as hemorrhagic osteosarcoma [17] and designated by Ewing [18] as an osteogenic sarcoma variant, it was referred by Sir James Paget [19] as “medullary cancer of bone with an excessive development of blood vessels” and by Gaylord [20], as a malignant bone aneurysm in 1903. Those descriptions reflect the septated, aneurysmally-dilated cavities recognized on histologic examination [21].

Radiologic examination reveals a purely lytic geographic, permeative process localized centrally within long bone metaphyses [17,21-26], a characterization that Matsuno et al. [27] reported as diagnostic.

Case Presentation

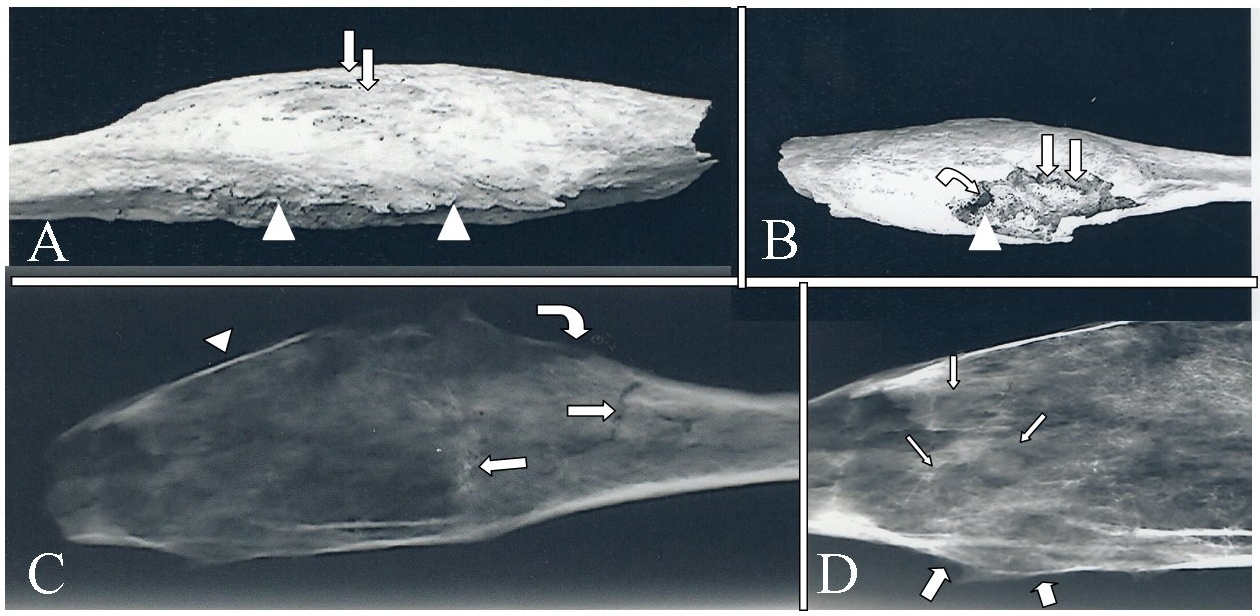

A previously healthy 29 year old Swiss Caucasian male presented in the early part of the 20th century with swelling at the lateral aspect of the leg, just proximal to the ankle. There were no other physical findings. Radiologic evaluation revealed fusiform expansion of the distal third of the fibula by a centrally located, permeative process. The resected fibula was macerated to remove soft tissues. Macroscopic examination of the defleshed bone revealed an expanded distal fibula with cortical breakthrough and slight focal periosteal reaction (Figures 1A and 1B). Radiologic examination revealed cortical thinning (to egg shell thickness) and permeation with perforation. Medullary density was irregular with subtle cystic areas, focal periosteal reaction, and a Codman’s triangle (Figures 1C and 1D). Residual trabeculae were not individually identifiable. Histological studies were not permitted.

Figure 1: Resected fibula with telangiectatic osteosarcoma. A. Lateral macroscopic view of expanded distal fibula. Arrows identify areas of cortical breakthrough. Arrowheads identify slight focal periosteal reaction. B. Medial macroscopic view of expanded distal fibula. Straight arrows identify post-mortem damage. Curved arrow identifies indistinct trabeculae. Arrowhead identifies cystic area. C. Lateral x-ray of expanded distal fibula. Straight arrows identify fracture lines. Curved arrow identifies focal periosteal reaction. Arrowhead identifies severe cortical thinning. D. High contrast, closeup view of C. Thin arrows identify subtle cystic areas. Thick arrows identify periosteal reaction with a Codman’s triangle.

Discussion

The actual bone damage caused by telangiectatic osteosarcoma is illustrated herein. The perspective provided supplements that obtainable by routine radiologic and histologic techniques. It documents the diffuse thin residual shell, highly characteristic of this disorder. This contrasts with other forms of osteosarcoma which, though less high grade than telangiectatic osteosarcomas, grow around residual cortex rather than diffusely leaving a thin rim [28].

The major differential consideration is aneurysmal bone cyst [8]. It was easy to dismiss in this case, given its diffuse, permeative appearance, with no evidence of internal struts or opaque rim, in contrast to the well-demarcated soap bubble appearance of aneurysmal bone cysts [11,29]. Similarly, absence of lobulation or internal struts eliminates giant cell tumor [5,30]. Internal calcifications (e.g., popcorn appearance), characteristic of chondrosarcoma and malignant fibrous dysplasia, and the lobulated nature of the latter [31-34] were not observed. Absence of a honeycomb appearance and sclerotic reaction permit hemangioendothelioma and cystic angiomatosis diagnoses to be dismissed [35]. Absence of well-defined margins and failure of survival of peri-lesional normal bone is not compatible with diagnosis of fungal disease or echinococcus (hydatid) disease [36-38]. Hyperparathyoidism and tuberculosis are associated with preservation of surrounding trabeculae and endosteal scalloping [5], at variance with what was observed in this individual. Osteomyelitis may also present as purely destructive, but associated abscesses (e.g., Brodie abscess have a sclerotic margin [5], contrasted with the subtle margins observed herein.

Conclusion

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma is a high grade bone tumor with characteristic amenable to its recognition in the archeologic and paleontologic record. As an expansile tumor which produces severe cortical thinning and minimal periosteal reaction, it is easily distinguished from aneurysmal bone cysts and giant cell tumors. Examination of the archeologic and paleontologic record should allow identification of the antiquity of this form of osteosarcoma and perhaps provide additional clues to its derivation.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

References

2. Cockburn A, Cockburn E, Reyman TA, editors. Mummies, disease and ancient cultures. Cambridge University Press; 1998.

3. Rothschild BM, Martin LD. Skeletal impact of disease: bulletin 33. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science; 2006.

4. Rothschild BM, Rothschild C. Comparison of radiologic and gross examination for detection of cancer in defleshed skeletons. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1995 Apr;96(4):357-63.

5. Resnick D (Editor). Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. Saunders; 2002.

6. Rothschild BM, Hershkovitz I, Dutour O. Clues potentially distinguishing lytic lesions of multiple myeloma from those of metastatic carcinoma. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 1998 Feb;105(2):241-50.

7. Rothschild B, Robinson L, Witt M, Koay J, Cline H. Radiologic/histologic discrepancies in tumour identification: The case of a “basketball‐sized” mandibular tumour in a woman from 17th century West Virginia. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 2018 Nov;28(6):775-81.

8. Zishan US, Pressney I, Khoo M, Saifuddin A. The differentiation between aneurysmal bone cyst and telangiectatic osteosarcoma: a clinical, radiographic and MRI study. Skeletal Radiology. 2020 Apr 5:1-2.

9. Haridy Y, Witzmann F, Asbach P, Schoch RR, Fröbisch N, Rothschild BM. Triassic cancer—osteosarcoma in a 240-million-year-old stem-turtle. JAMA Oncology. 2019 Mar 1;5(3):425-6.

10. Natarajan LC, Melott AL, Rothschild BM, Martin LD. Bone cancer rates in dinosaurs compared with modern vertebrates. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 2007 Jan;110(3):155-8.

11. Weiss A, Khoury JD, Hoffer FA, Wu J, Billups CA, Heck RK, et al. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma: The St. Jude children's research hospital's experience. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society. 2007 Apr 15;109(8):1627-37.

12. Janeczek M, Skalec A, Ciaputa R, Chrószcz A, Grieco V, Rozwadowski G, et al. Identification of probable telangiectatic osteosarcoma from a dog skull from multicultural settlement Polwica-Skrzypnik in Lower Silesia, Poland. International Journal of Paleopathology. 2019 Mar 1;24:299-307.

13. Goldschmidt B, Calado MI, Resende FC, Caldas RM, Pinto LW, Lopes CA, et al. Spontaneous telangiectatic osteosarcoma in a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Journal of Medical Primatology. 2017 Apr;46(2):51-5.

14. Brellou G, Papaioannou N, Patsikas M, Polizopoulou Z, Vlemmas I. Vertebral telangiectatic osteosarcoma in a dog. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2004 Sep;33(3):159-62.

15. Havilcek M, O'Connell K, Langova V. Feline Maxillary Telangiectatic Osteosarcoma in a Two-year-old Cat. Australian Veterinary Practitioner. 2008 Sep 1;38(3):92.

16. Gutierrez‐Nibeyro SD, Sullins KE, Powers BE. Treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in a horse. Equine Veterinary Education. 2010 Nov;22(11):540-4.

17. Greenspan A, Remagen W. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumor-like lesions of bones and joints.

18. Ewing J. A review and classification of bone sarcomas. Archives of Surgery. 1922 May 1;4(3):485-533.

19. Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology: Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Lindsay & Blakiston; 1865.

20. Gaylord HR. III. On the Pathology of So-called Bone Aneurisms. Annals of Surgery. 1903 Jun;37(6):834.

21. Chew FS. Skeletal radiology: the bare bones. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012 Mar 28.

22. Murphey MD, wan Jaovisidha S, Temple HT, Gannon FH, Jelinek JS, Malawer MM. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma: radiologic-pathologic comparison. Radiology. 2003 Nov;229(2):545-53.

23. Kulidjian A. Musculoskeletal tumors: Current approaches and controversies. SICOT-J 2018;4:e2017028.

24. Robert E. Fechner, Stacey E. Mills. Tumors of the bones and joints. Amer Registry of Pathology; 1993.

25. Liu JJ, Liu S, Wang JG, Zhu W, Hua YQ, Sun W, et al. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma: a review of literature. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2013;6:593.

26. Misaghi A, Goldin A, Awad M, Kulidjian AA. Osteosarcoma: a comprehensive review. Sicot-j. 2018;4.

27. Sangle NA, Layfield LJ. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2012 May;136(5):572-6.

28. Mervak TR, Unni KK, Pritchard DJ, McLEOD RA. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1991 Sep(270):135-9.

29. Farr GH, Huvos AG, Marcove RC, Higinbotham NL, Foote Jr FW. Telangiectatic osteogenic sarcoma: A review of twenty‐eight cases. Cancer. 1974 Oct;34(4):1150-8.

30. Kransdorf MJ, Sweet DE. Aneurysmal bone cyst: concept, controversy, clinical presentation, and imaging. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1995 Mar;164(3):573-80.

31. Spjut HJ. Tumors of bone and cartilage. US Department of Defense, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1971.

32. Feldman F, Norman D. Intra-and extraosseous malignant histiocytoma (malignant fibrous xanthoma). Radiology. 1972 Sep;104(3):497-508.

33. Moser RP. Cartilaginous tumors of the skeleton. Hanley & Belfus; 1990.

34. Murphey MD, Gross TM, Rosenthal HG. From the archives of the AFIP. Musculoskeletal malignant fibrous histiocytoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994 Jul;14(4):807-26.

35. Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma. An analysis of 200 cases. Cancer. 1978 Jun;41(6):2250-66.

36. Requena L, Kutzner H. Hemangioendothelioma. InSeminars in diagnostic pathology 2013 Feb 1 (Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 29-44). WB Saunders.

37. Booz MY. The value of plain film findings in hydatid disease of bone. Clinical Radiology. 1993 Apr 1;47(4):265-8.

38. Hershkovitz I, Rothschild BM, Dutour O, Greenwald C. Clues to recognition of fungal origin of lytic skeletal lesions. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 1998 May;106(1):47-60.

39. Torricelli P, Martinelli C, Biagini R, Ruggieri P, De Cristofaro R. Radiographic and computed tomographic findings in hydatid disease of bone. Skeletal Radiology. 1990 Aug 1;19(6):435-9.