Abstract

Elucidation of the nature of non-covalent interactions that govern the rate-limiting cis-trans isomerism at Xaa-Pro peptide bonds is fundamental to unravelling the protein folding mechanism, the stereoelectronic control elements of the structure and dynamics of the peptide bond, and the design of novel peptide isosteres. CisPro rotamers are stabilized by very few interactions compared to the transPro rotamer and are hence relatively scarcely populated. Design of novel interactions that can bias cisPro stability, with least mutations to the prolyl peptide bond, is crucial for accessing the cisPro motif in a variety of peptides. This mini review discusses the various interactions tailored for improving cisPro stability.

Keywords

cisPro, Stabilization, Non-covalent, Interactions, cis/trans isomerism

Abbreviations

Pro: Proline; Aro: Aromatic; Alp: Aliphatic; H-bond: Hydrogen bond; NMR: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, vdW: van der Waals

Introduction

cis/trans rotational isomerism at Xaa-Pro is usually the rate-limiting step during most protein folding processes [1]. The cis isomer is significantly less populated compared to trans. Survey of protein structures has shown that 0.03-0.05% [2-4] of Xaa-Xnp (Xaa is any residue and Xnp is a nonProline residue) peptide bonds and 5.2 to 6.5% [2-5] of all Xaa-Pro (Pro is proline) occur in cis form. Overall, only 0.3% of all peptide bonds occur in the cis form in protein crystal structures [6]. In solution as well cisPro is scarcely populated. The percentages vary with solvent polarities [7] and with the steric bulk of the prolyl peptide [8,9] Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies of cis–trans equilibrium in short peptides have shown that the Xaa-Pro motif exhibits the highest (23–38%) [10] cis content when Xaa is an aromatic residue, while the lowest cis content (6%) [10] is observed when Xaa is Pro.

Reasons for the Relatively Low Population of cisPro Compared to transPro

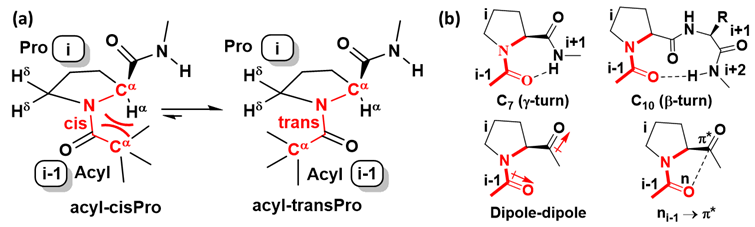

The relatively low percentage of cisPro is because it is stabilized by very few intramolecular non-covalent interactions along peptide sequences (Figure 1a), unlike transPro. TransPro on the other hand, is extensively stabilized by various local intramolecular non-covalent interactions including the γ-turn H-bond [11], β-turn H-bond [12] i-1…i peptide dipole-dipole interactions [13] i-1…i nàπ* interactions [14] (Figure 1b). In addition, cisPro is more destabilized due to Cαi-1)(Cαi steric (van der Waals) repulsive interactions, unlike transPro (Figure 1a). Hence, transPro are relatively more populated in solution, are the more prevalent rotamers in crystals, and their structures are well documented in a variety of sequences [5]. For both understanding and controlling the stability of the rare cisPro structures, it is important to elucidate all the forces and interactions governing their space, under various conditions.

Figure 1. (a) cis/trans isomerism at prolyl amide bond showing Cαi-1)(Cαi steric repulsion in cisPro; (b) Local intramolecular non-covalent interactions stabilizing transPro.

Synthetic Methods for Constraining cisPro

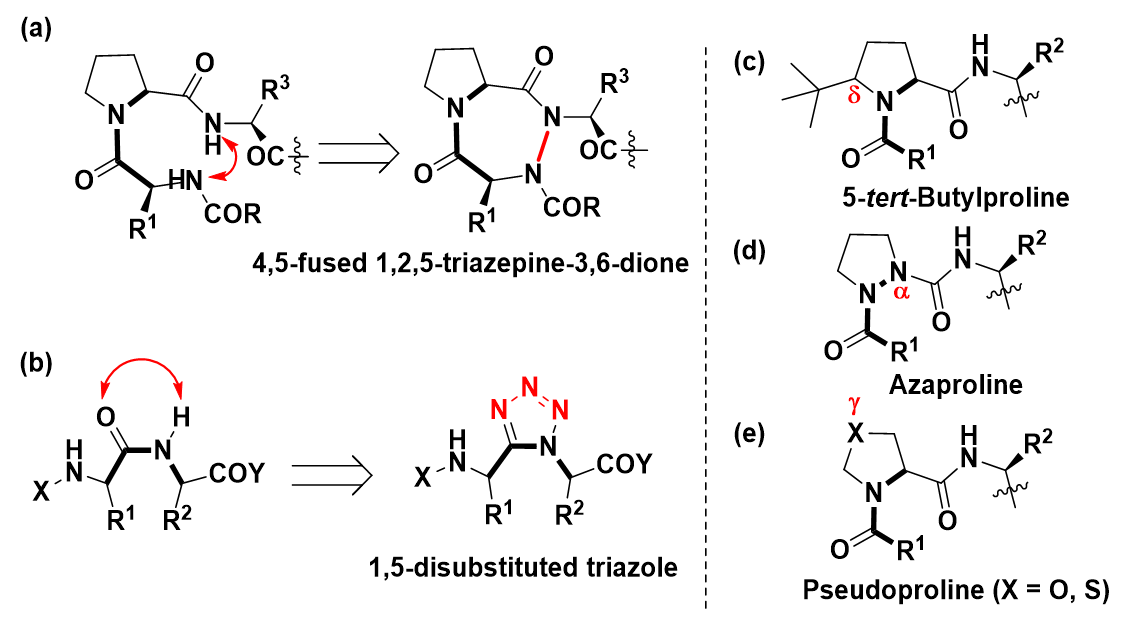

To counter the lack of natural interactions that stabilize the cis peptide bonds several cis peptide isosteres have been designed (Figure 2) that can synthetically restrict the peptide geometry to a cis-like conformer. The Xaa-Pro backbone [15] (Figure 2a) or the carbonyl of prolyl amide [16] (Figure 2b) can be restricted in order to constrain the peptide into a cisPro conformation. Another method involves modification of the stereoelectronic nature of pyrrolidine ring in Pro, by allowing for the selective introduction of sterically demanding tertiary alkyl substituents at the proline Cδ-position (Figure 2c). Since the steric repulsions between the bulkier Cδ-substituents and the N-terminal residue disfavour the X-Pro amide trans-isomer, they increase the cis-isomer population [17].

Figure 2. (a)-(e) Synthetic methods for stabilizing cisPro

The Cα [18] or Cγ [19], atoms of Pro can also be modified to heteroatoms N, O, S, giving rise to azaprolines [18,20] (Figure 2d) or pseudoprolines [19,21] (Figure 2e). Azaprolines (CαàN) stabilize the cisPro isomer in crystals [22] and in organic solvents [23]. Due to α-nitrogen lone-pair repulsion with the preceding carbonyl oxygen in the trans structure, the cisPro isomer population improves. In pseudoproline (CγàO/S) the electronegative heteroatom [24] withdraws electron density from the amide nitrogen. The double-bond character of the peptide bond [25] is consequently reduced, leading to higher cisPro populations.

In these methods, the Xaa-Pro backbone, and/or the pyrrolyl peptide bond, and/or the pyrrolidine ring of Pro, all of which are essential recognition elements, are structurally modified. Hence peptidomimetics that can improve the cis/trans isomer ratios without modifying these recognition elements have been more sort after to precisely probe the origins of bioactivity in prolyl peptides.

Local Interactions That Stabilize cisPro in Proteins and Peptides

In earlier studies on prolyl cis/trans isomerism by NMR, Grathwohl and Wuthrich, observed that the cisàtrans isomerization rates in H-Xaa-Pro-OH dipeptides slows by ~10 fold when Xaa was Aro (has aromatic side chains), compared to when Xaa is Ala [26]. Based on this result, the authors speculated, for the first instance in literature, that the aromatic ring and the proline ring probably have the tendency to form interactions – which could be the reason for the observed rate differences.

Through 1H NMR studies on short peptide sequences, Kemmink and Creighton [27] found that peptides and unfolded proteins with the sequence Xaai-1-Proi-Tyri+1 or Xaai-1-Proi-Phei+1 have a relatively strong local interaction (~ –3 kcalmol-1) that involve the aromatic ring of the i+1st residue and either the side-chain of Proi (the Aro(i+1)/SC(i) interaction) or the Hα of Xaai-1 (the Aro(i+1)/Hα(i-1) interaction), exclusively when the Xaa-Pro peptide bond adopts the cis form. Thus, at Xaai-1-Proi-Aroi+1 sequences, even in unfolded proteins, there is some local order through formation of the i-1…i+1 inter-residue interactions that stabilizes the Xaa-cisPro amide conformation.

- Pro-Aro and Aro-Pro sequences in protein crystal structures

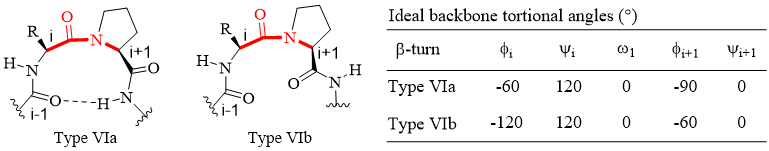

Type VI β-turns are the only ordered structures where the Xaa-cisPro motif is observed with any regularity [5]. These structures, where a cis amide bond exists between the i and i+1 (Pro) residues of the turn, are classified into two sub-types (VIa, VIb) based on the dihedral angle values of their central i and i+1 (Pro) residues (Figure 3) [28].

Figure 3. Geometry of Type VIa and VIb β-turns.

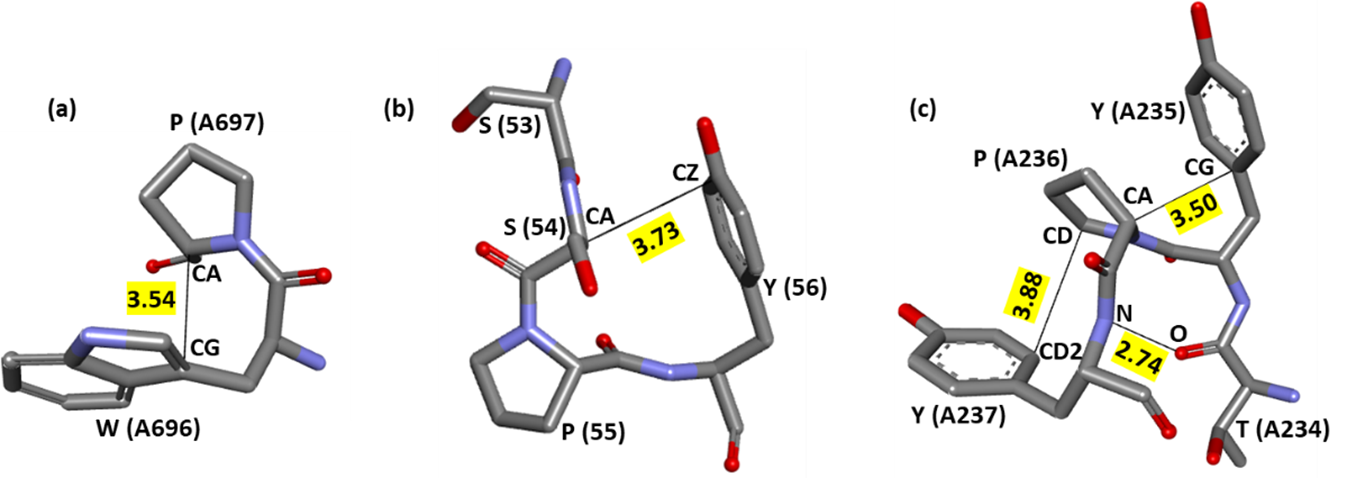

In a statistical analysis of protein crystal structures in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank, aromatic–prolyl (Aro-Pro) interactions have been observed to stabilize type VI β-turns and hence increase the frequency of occurrence of the cisPro isomer (Figure 4) [6]. In most of these type VI β-turns, the CαPro×××CgAro distance is ≤ 3.7 Å. Based on this, it has been proposed that the specific orientation of HαPro proton towards the Aro side chain seems to enable an apparent CαPro–HαPro···pAro (C-H···p) interaction. In Pro-Aro sequences as well, the HαPro protons are close (≤ 4.4 Å) to the Aro ring, implicating the existence of the CH···π interactions. These cis-stabilising local interactions have been suggested to be the reason for the increased frequency of occurrence of the cisPro isomer in Aro-Pro and Pro-Aro sequences.

Figure 4. Proposed local C-H···π interaction in Aro-Pro and Pro-Aro cis peptide units; the atoms involved in the shortest contact (black line) are labelled, as are the residues. (Reproduced from [6]).

- Pro-Aro and Aro-Pro sequences in short peptides

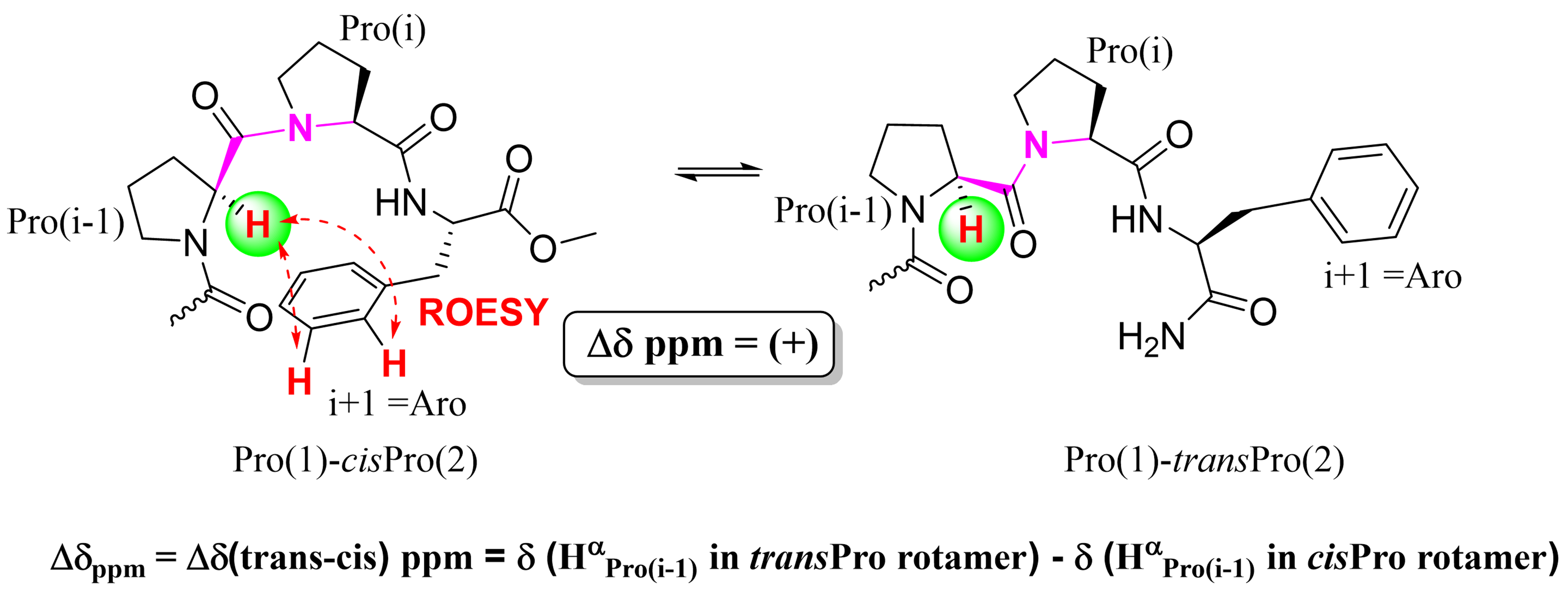

NMR analyses of the cis/trans isomerism at Pro-Pro peptide bond in Proi-1-Proi-Xaai+1 sequence containing short peptides in solution revealed [29] that when Xaai+1 is an aromatic residue, (i) the Hα of the N-terminal Proi-1 (HαPro(i-1)) is upfield shifted and (ii) NOE cross peaks are observed between HαPro(i-1) and the aromatic ring of the Aro side chain (Figure 5). These are indicators of local (i-1…i+1) Cαi-1-Hαi-1···πi+1 interactions formed in these models. These interactions stabilize the cis conformation of the Proi-1-Proi amide bond and increases the cisPro population by upto 4.9 times when Xaai+1 is aromatic compared to when it is aliphatic. In Aro-Pro sequences as well, such cisPro stabilization has been observed [30].

Figure 5. Proposed indicators of Cαi-1-Hαi-1···πi+1 interactions in Proi-1-Proi-Aroi+1 peptide models: Upfield shifts of HαPro(i-1) and ROESY cross peaks between HαPro(i-1) and πi+1.

- Anomalous properties of Pro-His

Unlike other aromatic side chains, at Pro-His sequences the cisPro populations are anomalously diminished (Cαi-1-Hαi-1···πi+1 absent) [29]. In proteins His is conspicuously less conserved at Xaai-1-cisProi-Aroi+1, compared to when Aro is Phe, Tyr or Trp [29]. Investigation of the presence of anomalous weak H-bonding interactions revealed the formation of an i → i backbone-side chain C6 H-bond between the amide NH and the imidazole N exclusively when Aro is His (Figure 6) [31]. This significantly decreases the population of the χ1-g- rotamer essential for Cαi-1-Hαi-1···πi+1 formation, leading to the anomalous properties of His compared to other Aro amino acids.

Figure 6. The predominant conformations of model peptides, (a) iBu-Pro-Phe-OMe and (b) iBu-Pro-His-OMe (iBu is isobutyroyl), consistent with NMR spectral data (10 mM in DMSO-d6, CDCl3). (Reproduced from [31]).

- Pro-Alp sequences in short peptides

The presence of local (i-1…i+1) van der Waals (vdW) interactions were discovered, that exclusively stabilize the cisPro conformation in Xaai-1-Proi-Yaai+1 sequences even when both Xaa and Yaa are aliphatic [32]. By expanding the interaction volume of the aliphatic side chains of Yaai+1 (Val, Ile, Leu, cyclohexylalanine), a sigmoidal increase in cis amide stabilization was observed by up to -0.24 kcal mol-1 (Figure 7). The population of cisPro isomer increases correspondingly, explaining the stabilization of cisPro in Alpi-1-Proi-Alpi+1 sequences in proteins like the urease accessory protein UreF.

Figure 7. Sigmoidal correlations of Kc/t (black) and ΔG (kcal mol-1) (red), with the quarter-sphere vdW residence volumes of the Alpi+1 side chains (V Å3) of 1-5 in the vicinity of iBui-1. The transitions are in the range of 0–95 Å3 (orange). (Reproduced from [32]).

- What is the mechanism by which an i-1…i+1 interaction affects the prolyl amide cis/trans equilibrium?

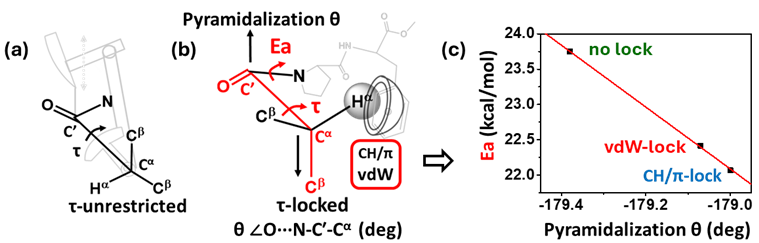

Local i-1…i+1 vdW and CH···π interactions in iBui-1-Proi-Xaai+1-OMe peptide models “lock” the rotation along the isobutyryl (iBui-1) Cα-C′ bonds (τ torsion) [33] (Figure 8). DFT calculations reveal that such locking synchronously affects pyramidalization (torsion θ) at the prolyl amide in order to avoid gauche interactions. This perturbs the planarity of the amide and leads to an observable decrease in energy barrier (Ea) (∼1.68 kcal/mol) for the amide cis/trans isomerism in solution. Ea decreases linearly with increasing pyramidalization. These i-1…i+1 interactions are the second known, apart from the amide N-hydrogen bonding interactions in peptidylprolyl isomerases (PPIs) [34], to effect attenuation of Ea and their effects are comparable to those of PPIs (∼1.40 kcal/mol).

Figure 8. Model in which rotation along Cα-C′ bond (τ) is (a) unrestricted, (b) locked by a CH···π or vdW interaction; (c) Corresponding drop in activation energy barrier of prolyl amide cis/trans isomerism. (Reproduced from [33]).

- Another method for stabilizing the cis prolyl peptide bond: influence of an unusual nàπ* interaction in 1,3-oxazine and 1,3-thiazine containing peptidomimetics

Selective stabilization of cisPro by nàπi-1* interactions has been reported in peptidomimetics containing the 5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-oxazine (Oxa) and 5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-thiazine (Thi) functional groups at the C-terminus of Pro [35]. An unusual reverse nOxaàπ*i-1 interaction in the cis, and the n (n repulsion in the trans conformers of these molecules) combine to result in such cis stabilization (Figure 9). These interactions increase the cis/trans equilibrium constant (Kc/t) values remarkably (up to 9). It is notable that the Oxa and Thi operate remotely away from the recognition elements of the prolyl peptide bond.

Figure 9. (a) Proposed method for stabilizing the Xaa-cisPro conformer using a reverse nOxaàπ*i-1 interaction. The structure destabilizing lone pair-lone pair Pauli repulsions between the carbonyl oxygen of Xaa and imidate nitrogen selectively exist in the transPro conformation. (b) NBO rendition of the overlap between the nOxa and π*i-1 orbitals of the cis Cγ-endo isomer of Ac-Pro-Oxa. (Reproduced from [35]).

- Stabilizing the sterically most hindered Piv-cisPro in crystal structures

A remotely placed nàπ* interactions has been utilized to stabilize cisPro even in the elusive pivaloyl-proline (Piv-Pro) peptide bond. It is known that steric clashes between substituents of CαXaa(i-1) and CαPro(i) at Xaai-1-Proi sequences destabilize cis conformers (Figure 1a). Piv-Pro represents the extremity of such clashes and was thought to be inaccessible. First access to this cis conformer was made in crystals of Piv-Pro-Aib-OMe (2) [36]. Comparison of the structures of 2 with those of 1 and 3 revealed the presence of strong nàπ* interactions between the lone electron pair (n) on the oxygen atom of Pro (OPro) and the π* orbital of the carbonyl group of Aib (C′Aib) (Figure 10a), whose formation is assisted by Thorpe-Ingold effect at the tetrasubstituted Cα of Aib. This results in partial restriction of the rotation of the COPro group and creates a vacant volume where CαPiv substituents can exist with lesser steric encumbrance. The nàπ* interaction energy also compensates for the energy lost due to various structural distortions (Figure 10b) caused while avoiding steric clashes in these peptides.

Figure 10. (a) ChemDraw representation of compounds 1, 2 and 3 and NBO view 1.0 rendering of the n→π* (OPro→C′Aib) interactions with corresponding interaction energies. (b) Distortions in the ω dihedral angle in 1-3. (Reproduced from [36]).

- Stabilizing the sterically most hindered Piv-cisPro in solution

In crystals, molecules may gain conformational stability from packing forces which are mostly absent in solution. The significant population of Piv-cisPro was evidenced in solution by their FT-IR and low temperature NMR spectral signals (Figure 11) for Piv-Pro-Aib-OMe peptide in CDCl3. There is presence of nàπ* (OPro→C′Aib) orbital overlap interactions at Aib as in crystals. The equilibrium constant values (Kc/t) for Xaa-Pro-Aib-OMe peptides were studied in DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 using NMR, where the steric bulk at Cα of Xaa was systematically increased. Comparison of Kc/t revealed that the energy contribution of steric effects to the cis/trans equilibrium at the Xaa-Pro motifs is nonvariant (0.54 ± 0.02 kcal/mol) despite increase in steric bulk on Cα of Xaa.

Figure 11. Partial stacked 1H-NMR (15 mM CDCl3, 400 MHz) of Piv-Pro-Aib-OMe with variable temperature showing freezing out of cis isomer at below 273K (0 °C) temperature. (Reproduced from [8]).

- What are the factors influencing the crystallization of Piv-cisPro and Piv-transPro?

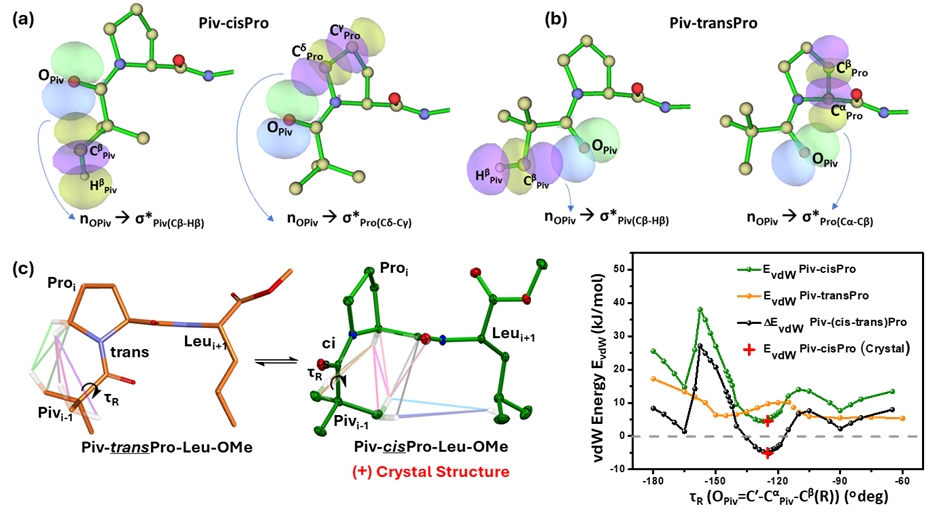

To investigate the stereoelectronic interactions influencing the relative stabilities of Piv-cisPro and Piv-transPro, the number, geometries and energies of the various non-covalent interactions present in the crystal structures of Piv-cisPro-Xaa-OMe (Xaa is Leu/Ile) (A, B) and Piv-transPro-Xaa-OMe (Xaa is Gly/Phe) (C, D) peptides were determined using NBO, QTAIM and DFT calculations and compared [37] There is consistent presence of two nàσ* and several vdW interactions in both Piv-cisPro and Piv-transPro (Figure 12). With rotation along the CαPiv-C′Piv bond (torsion τR), these interactions vary in numbers and relative energies. Although the net energy contribution of these interactions is >0 kcal/mol for all values of τR in both Piv-cisPro and Piv-transPro, the latter values are relatively much lower than the former and hence tend to be observed in solution and in crystals (Figure 12c). Interestingly however, in a narrow range of 12° of τR the energies are relatively more favourable for Piv-cisPro than Piv-transPro (Figure 12c). In A, B due to presence of interactions that lock τR with in this range their Piv-Pro crystallize in the cis conformer. Understanding the interactions governing the Piv-Pro cis/trans isomerism provides access to the sterically hindered Piv-cisPro, which is a close mimic of the Aib-cisPro tertiary amide bond extensively found in biologically relevant peptides [38].

Figure 12. NBO renditions of: (a) the nOPiv à σ*Piv(Cβ-Hβ) and nOPiv à σ*Pro(Cδ-Cγ) orbital overlap interactions at Piv-cisPro conformer and (b) the nOPiv à σ*Piv(Cβ-Hβ) and nOPiv à σ*Pro(Cα-Cβ) orbital overlap interactions at Piv-transPro conformer. (c) Network of vdW interactions in cisPro and transPro and plots of net vdW interactions. (Reproduced from [37]).

Biological Relevance

Several of these strategies have been applied to attenuate the cisPro stabilities in proteins and peptides. The conserved fold of thioredoxin (Trx)-like oxidoreductases contains an invariant cis-proline residue that is responsible for the rate-limiting step in the protein folding process and is essential for Trx function [39]. In order to overcome this bottleneck in protein folding, the cisPro76 in E. coli thioredoxin1P (Trx1P) was substituted with the pseudoproline 4-thiaproline (Thp). This significantly reduced the half-life of the refolding reaction from ~2 h to ~35 s [40]. Similar acceleration of the refolding rate was also observed for the protein pseudo wild-type barstar upon replacement of cisPro48 with Thp [40]. The protein variants retained their thermodynamic stability upon incorporation of Thp, while the catalytic and enzymatic activities remained unchanged.

The Aro-Pro and Pro-Aro sequences in Coturnix japonica Osteopontin (OPN), show significant local rigidification of the protein backbone by favoring the cisPro conformation [41]. These constrained sites nucleate the structural compaction in intrinsically disordered protein (IDPs) as their restricted motion reduces the entropic penalty for the formation of native states. The emerging strategies for cisPro stabilization using vdW and CH···π interactions at Xaa-Pro-Alp and Xaa-Pro-Aro sequences respectively are expected to be crucial in exerting similar control over protein folding and function in the future.

Conclusions

This mini-review provides a summary of some of the interactions tailored at various peptide sequences (Pro-Aro, Aro-Pro, Alp-Pro-Alp, etc) to stabilize the cisPro isomer. Early methods of stabilizing cisPro perturbed the essential recognition elements of the Xaa-Pro backbone and side chain. Later improved methods were introduced that exploited the non-covalent vdW and CH···π i-1…i+1 interaction naturally present at Xaai-1-Proi-Yaai+1 sequences (Yaa is Alp, Aro respectively) in order to reduce the activation energy barrier of cis-trans isomerism and hence increase the population of the cisPro isomer. Clear elucidation of the different interactions stabilizing cisPro enabled the crystallization of even the sterically most hindered Piv-cisPro conformer. Other non-covalent interactions that stabilise cisPro like the reverse nOxa à π*i-1 in Xaa-Pro-Oxa, n à π* (OPro→C′Aib) in Xaa-Pro-Aib-OMe have also been discussed. Understanding the relationship between the prolyl amide cis/trans isomerism and the stereoelectronic effects at X-Pro tertiary amide motifs in short peptides provides predictable control over design of folds in longer and biologically significant peptides and proteins containing these motifs.

References

2. Stewart DE, Sarkar A, Wampler JE. Occurrence and role ofcis peptide bonds in protein structures. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990 Jul 5;214(1):253-60.

3. Weiss MS, Jabs A, Hilgenfeld R. Peptide bonds revisited. Nature Structural Biology. 1998 Aug;5(8):676.

4. Jabs A, Weiss MS, Hilgenfeld R. Non-proline cis peptide bonds in proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999 Feb 12;286(1):291-304.

5. MacArthur MW, Thornton JM. Influence of proline residues on protein conformation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1991 Mar 20;218(2):397-412.

6. Pal D, Chakrabarti P. Cis peptide bonds in proteins: residues involved, their conformations, interactions and locations. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999 Nov 19;294(1):271-88.

7. Sugawara M, Tonan K, Ikawa SI. Effect of solvent on the cis–trans conformational equilibrium of a proline imide bond of short model peptides in solution. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2001 May 1;57(6):1305-16.

8. Reddy DN, Prabhakaran EN. Steric and electronic interactions controlling the cis/trans isomer equilibrium at X‐pro tertiary amide motifs in solution. Biopolymers. 2014 Jan;101(1):66-77.

9. Liang GB, Rito CJ, Gellman SH. Variations in the turn‐forming characteristics of N‐Acyl proline units. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules. 1992 Mar;32(3):293-301.

10. Reimer U, Scherer G, Drewello M, Kruber S, Schutkowski M, Fischer G. Side-chain effects on peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerisation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998 Jun 5;279(2):449-60.

11. LONDON RE. QUANTITATIVE EVALUATION OF γ‐TURN CONFORMATION IN PROLINE‐CONTAINING PEPTIDES USING13 C NMR. International Journal of Peptide and Protein Research. 1979 Nov;14(5):377-87.

12. Gallo EA, Gellman SH. Hydrogen-bond-mediated folding in depsipeptide models of. beta.-turns and. alpha.-helical turns. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1993 Oct;115(21):9774-88.

13. Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Interstrand dipole-dipole interactions can stabilize the collagen triple helix. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011 Jul 1;286(26):22905-12.

14. Newberry RW, Raines RT. The n→ π* Interaction. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2017 Aug 15;50(8):1838-46.

15. Lenman MM, Ingham SL, Gani D. Syntheis and structure of cis-peptidyl prolinamide mimetics based upon 1, 2, 5-triazepine-3, 6-diones. Chemical Communications. 1996(1):85-7.

16. Tam A, Arnold U, Soellner MB, Raines RT. Protein prosthesis: 1, 5-disubstituted [1, 2, 3] triazoles as cis-peptide bond surrogates. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007 Oct 24;129(42):12670-1.

17. Beausoleil E, L'Archevêque B, Bélec L, Atfani M, Lubell WD. 5-tert-Butylproline. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1996 Dec 27;61(26):9447-54.

18. Zhang WJ, Berglund A, Kao JL, Couty JP, Gershengorn MC, Marshall GR. Impact of azaproline on amide cis− trans isomerism: Conformational analyses and NMR studies of model peptides including TRH analogues. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003 Feb 5;125(5):1221-35.

19. Keller M, Sager C, Dumy P, Schutkowski M, Fischer GS, Mutter M. Enhancing the proline effect: pseudo-prolines for tailoring cis/trans isomerization. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998 Apr 1;120(12):2714-20.

20. Che Y, Marshall GR. Impact of azaproline on peptide conformation. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2004 Dec 24;69(26):9030-42.

21. Dumy P, Keller M, Ryan DE, Rohwedder B, Wöhr T, Mutter M. Pseudo-prolines as a molecular hinge: reversible induction of cis amide bonds into peptide backbones. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997 Feb 5;119(5):918-25.

22. Didierjean C, Duca VD, Benedetti E, Aubry A, Zouikri M, Marraud M, et al. X‐ray structures of aza‐proline‐containing peptides. The Journal of Peptide Research. 1997 Dec;50(6):451-7.

23. Zouikri M, Vicherat A, Aubry A, Marraud M, Boussard G. Azaproline as a β‐turn‐inducer residue opposed to proline. The Journal of Peptide Research. 1998 Jul;52(1):19-26.

24. Kang YK. Cis− Trans Isomerization and Puckering of Pseudoproline Dipeptides. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2002 Feb 28;106(8):2074-82.

25. Kern D, Schutkowski M, Drakenberg T. Rotational barriers of cis/trans isomerization of proline analogues and their catalysis by cyclophilin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997 Sep 10;119(36):8403-8.

26. Grathwohl C, Wüthrich K. NMR studies of the rates of proline cis–trans isomerization in oligopeptides. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules. 1981 Dec;20(12):2623-33.

27. Kemmink J, Creighton TE. The physical properties of local interactions of tyrosine residues in peptides and unfolded proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1995 Jan 20;245(3):251-60.

28. Richardson JS. The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 1981 Jan 1;34:167-339.

29. Ganguly HK, Majumder B, Chattopadhyay S, Chakrabarti P, Basu G. Direct evidence for CH··· π interaction mediated stabilization of pro-cis pro bond in peptides with pro-pro-aromatic motifs. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012 Mar 14;134(10):4661-9.

30. Thomas KM, Naduthambi D, Zondlo NJ. Electronic control of amide cis− trans isomerism via the aromatic− prolyl interaction. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006 Feb 22;128(7):2216-7.

31. Gupta SK, Banerjee S, Prabhakaran EN. Understanding the anomaly of cis–trans isomerism in Pro-His sequence. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2022 Nov 15;76:128985.

32. Gupta SK, Banerjee S, Prabhakaran EN. van der Waals interactions to control amide cis–trans isomerism. New Journal of Chemistry. 2022;46(26):12470-3.

33. Banerjee S, Gupta SK, Prabhakaran EN. Direct Evidence for Synchronicity between Rotation along Cα− C′ and Pyramidalization of C′ in Amides. ChemistrySelect. 2023 May 5;8(17):e202301105.

34. Cox C, Lectka T. Intramolecular catalysis of amide isomerization: kinetic consequences of the 5-NH--Na hydrogen bond in prolyl peptides. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998 Oct 21;120(41):10660-8.

35. Reddy DN, Thirupathi R, Tumminakatti S, Prabhakaran EN. A method for stabilizing the cis prolyl peptide bond: influence of an unusual n→ π∗ interaction in 1, 3-oxazine and 1, 3-thiazine containing peptidomimetics. Tetrahedron Letters. 2012 Aug 15;53(33):4413-7.

36. Reddy DN, George G, Prabhakaran EN. Crystal‐Structure Analysis of cis‐X‐Pro‐Containing Peptidomimetics: Understanding the Steric Interactions at cis X‐Pro Amide Bonds. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013 Apr 2;52(14):3935-9.

37. Banerjee S, Gupta SK, Pal S, Prabhakaran EN. Crystal structures reveal that the sterically hindered pivaloyl-cisProlyl amide bond is energetically frustrated. Peptide Science. 2024 Jan 8:e24337.

38. Nagaraj R, Balaram P. Alamethicin, a transmembrane channel. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1981 Nov 1;14(11):356-62.

39. Eklund H, Gleason FK, Holmgren A. Structural and functional relations among thioredoxins of different species. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 1991 Sep;11(1):13-28.

40. Loughlin JO, Zinovjev K, Napolitano S, Van der Kamp M, Rubini M. 4-Thiaproline accelerates the slow folding phase of proteins containing cis prolines in the native state by two orders of magnitude. Protein Science. 2024 Feb;33(2):e4877.

41. Mateos B, Conrad-Billroth C, Schiavina M, Beier A, Kontaxis G, Konrat R, et al. The ambivalent role of proline residues in an intrinsically disordered protein: from disorder promoters to compaction facilitators. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2020 Apr 17;432(9):3093-111.