Abstract

Sézary's Syndrome consists of a rare type of non-Hodgkin cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), being a very aggressive leukemic variant of CTCL. Given its rarity and its ability to mimic other more common diseases, this neoplasm represents a major diagnostic challenge for both clinicians and pathologists. In this sense, a Literature review focused on natural history, clinical presentations, diagnostic methods in studies published in the last 5 years in the Pubmed and Scielo databases was made. Altogether 23 articles were included in this research. We also highlight the need for further studies to identify new diagnostic markers. Besides, we reiterate the importance of clinical correlation with laboratory and histological findings.

Keywords

Lymphoma, T Cell, Neoplasms; Lymphoproliferative Disorders, Disease; Skin Diseases, Pathology

Introduction

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas (CTCL) are a very heterogeneous group of proliferative T-cell disorders that differ in both clinical and histological aspects [1,2]. Although mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) are the two most common types of CTCL, SS is nonetheless an uncommon disease, with an incidence of 2.5% on all cases of LCCT, with the MF being the protagonist of the group [1,3]. Its incidence in the United States is 0.8-0.9/1,000,000, with approximately 300 new cases per year [4,5]. SS, first described in 1938 by the French dermatologist Albert Sézary, whose name today designates the syndrome characterized by exfoliative rash (exfoliative erythroderma), intense itching, lymphadenopathy and blood involvement with monstrous TCD4 lymphocytes of cerebriform nucleus, called Sézary cells (CS) [2,5-7].

The SS shows a higher prevalence in adult male individuals (2: 1 ratio), especially those of older age (mean of 60 years). [4,6,7]. However, this gender discrepancy is not seen in patients under 30 years of age [9]. Regarding ethnicity, despite the fact that LCCTs have a higher incidence on African-Americans, SS behaves in a contrary way to other members of the group, with a high incidence in whites [2,6]. As a result, white men over the age of 50 are more likely to develop the syndrome [4]. There are no studies that prove the genetic predisposition of the disease [4]. The aggressiveness of this non-Hodgkin lymphoma justifies the average 2 to 4 year survival rate since diagnosis [5,6].

Although studies on the syndrome are increasing, the diagnosis of the disease is still a major challenge for clinicians, whether due to the non-specificity of histopathological findings, the rarity, or the need for clinical-pathological correlation and molecular studies [6,8]. The guiding question of this study was to present a literary review on the natural history of the disease, possible clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis and available diagnostic tools, as well as the disease staging.

Material and Methods

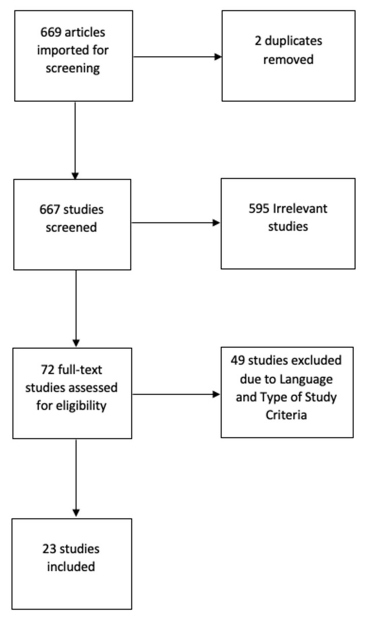

The present study is a Literature Review based on studies published in the databases of the US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (PubMed) and the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), through descriptor “Sézary Syndrome”. The selection of studies was carried out in 3 phases (Figure 1). The first consisted of filtering the articles found using the descriptor “Sézary Syndrome” and the filters of date of publication for the last 10 years and type of article: “Journal Article, Books and Documents; Classical Article; Guideline; Multicenter Study; Review; Systematic Review; Meta-Analysis”. This first phase resulted in to 669 papers. In the second phase, the remainder were subjected to a filtering process based on reading the titles, abstracts and checking the type of study, your language and your main content. Thus, studies with an original English language were included and whose thematic focus was: the histopathology and morphology of the lesions, history, clinical picture and diagnosis. Thus, only 23 studies remained, which were read in full of their content (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Treatment outcomes in patients with PAC. OS (overall survival) is reported in months. NAT: Neoadjuvant Therapy.

Natural History and Clinical Presentation

The SS shows a higher prevalence in adult male individuals (2: 1 ratio), especially those of older age (mean of 60 years) [4,6,7]. However, this gender discrepancy is not seen in patients under 30 years of age [9]. Regarding ethnicity, although LCCTs have a higher incidence on African-Americans, SS behaves in a contrary way to other members of the group, with a high incidence in whites [2,6]. As a result, white men over the age of 50 are more likely to develop the syndrome [4]. There are no studies that prove the genetic predisposition of the disease [4]. The aggressiveness of this non-Hodgkin lymphoma justifies the average 2 to 4 year survival rate since diagnosis [5,6].

In the early stages of the disease, his skin lesions can easily mimic other erythrodermic dermatoses, with erythroderma being the main finding [4]. SS classically presents with a triad composed of: erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy (≥ 1.5 cm in size) and invasion of the skin, blood and lymph nodes by Sézary cells [7]. Originating from a diffuse inflammatory process through the dermis, erythroderma is a syndrome defined by the presence of erythema on more than 80% of the body surface, with a pruritic-scaling character. This diffuse rash is the main cutaneous sign presented in the early stages of the disease, being the most striking difference concerning MF, which is present mainly through erythematous plaques. [4,10]. Erythroderma can often evolve with worsening or with the appearance of plaques and new skin lesions, which can be hypo or hyperpigmented and even ulcerated [3,4]. Sporadically, patients may not present this classic sign, which does not provide a better prognosis, but reveals limitations both in the clinical triad and in the diagnostic criterion of the disease, which requires erythroderma [10-12]. It is worth noting that many cases of SS without this rash in the early stages, evolve with the appearance of this finding [6,12].

On the other hand, there are skin and gender abnormalities that are described as non-classic signs of SS, for example, keratoderma, onychodystrophy, alopecia [5]. Palmoplantar keratoderma is the most common non-classic sign and an alarming condition that must be treated immediately, given that the created fissures can predispose infections, such as cellulitis and other diseases caused by Staphylococcus aureus, mainly [3,4,13]. SS, in general, is associated with onychodystrophy, associated with the treatment of the disease itself. However, these changes may be due to the involvement of the nail bed by a non-specific chronic lymphocytic infiltrate. In a single-center study, Damascus et. al. analyzed 19 cases of SS, where paronychia (63% of cases) was the main finding, followed by leukonychia, onycholysis, trachynonychia, among others [14]. The studies by Park et. al indicated that the changes in nails, out of a total of 86 study cases, 36 had this phenotype. The most frequent findings were thickening of the nails, yellow nails, subungual hyperkeratosis, among others [15].

Also, 10% of patients can develop alopecia [13]. Histological studies reveal the SC surrounding the hair follicles, which indicates that these cells cause direct and indirect damage to the keratinocytes of the follicles, culminating in alopecia [13].

Even rarer cases have leonine facies, which is associated with a worse prognosis, since this finding is often associated with infections by Staphylococcus aureus. Moreover, ocular manifestations, other visceral disorders and B symptoms (fever, night sweats and weight loss) are non-classic signs of very low incidence [4,6,13].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SS necessarily involves the association of clinical, histopathological and biochemical findings. In this sequence, the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) developed a hematological diagnostic criterion for SS. This criterion consists of 5 items: CS count ≥ 1000 cells/mm3; CD4 / CD8 ratio ≥ 10 evidenced by flow cytometry; lymphocytosis with clonal T lymphocytes evidenced by the Southern-Blot technique or by Polymerase Chain Reaction; chromosomally abnormal T lymphocyte clones. The presence of these 5 hematological findings, together with the generalized erythroderma makes the diagnosis definitive [16].

Histopathology

Among the main possible findings in the histopathological study of skin lesions, we have a perisvascular lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermo-epidermal junction, with atypical eosinophils and lymphocytes, usually small to medium in size, with cerebriform, hyperchromatic nucleus and surrounded by halos [6,17,18]. The perivascular organization of the lymphocytic infiltrate was seen in approximately 80% of cases in one study [19]. In most cases, epidermotropism is considerably reduced or even absent in SS, when compared to MF, which makes the diagnosis difficult, but it serves as an important data that can contribute to removing MF [3,6,17]. However, the epidermotropism of SS is still more pronounced than that found in erythrodermic dermartoses [19]. Pautrier's microabscesses, intraepidermal collections of malignant cells, are relatively common in skin biopsies, diverging from the expected pattern for inflammatory erythrodermic dermatoses, where in the vast majority of cases, these are absent [3,19].

Despite being an essential tool in the diagnosis of SS, the histology of skin lesions is still nonspecific in most cases, since the histopathological findings are quite similar to those of MF [17,20]. As a result, about 40% of SS cases have a non-specific histopathological analysis [6,17]. Therefore, histopathological analysis cannot be used as the sole diagnostic criterion, but it can be used for confirmation and should always be associated with clinical and hematological findings, such as peripheral blood flow cytometry, for example [6,17].

Since it is a leukemic variant of MF, SS is usually characterized by involvement of peripheral blood and bone marrow, in addition to lymph nodes [4]. Lymph nodes infiltrated by CS end up losing their nodal histology, and the infiltrate can be organized in the form of a dermatopathic lymphadenitis [21,22].

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical study, in the same way as MF, show an immunoreactivity for CD3, CD4, and, in most cases, negativity for CD8 (Table 1), which points to a cutaneous CD4+ helper T lymphoma [17,21,23,24]. This expected pattern justifies the CD4/CD8 ratio >10 as a diagnostic criterion, however, some cases may have a negative CD4 profile [23]. Typically, atypical T lymphocytes have a reduction in the expression of some antigens expressed by normal mature lymphocytes [3,25].

Klemke et. al [19] analyzed the expression of immunomarkers in skin biopsies of 97 patients, 57 of whom were diagnosed with SS following the ISCL criteria, while the rest comprised patients with some erythrodermic dermatoses. Their results showed that the loss of CD7 protein expression in skin biopsies is an important indicator of SS, being present in more than 60% of cases. Besides, most cases have negative CD30, FOXP3 and CD25. On the other hand, the markers Ki-67, the Antigen associated with Melanoma (MUM-1), Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) and CD158k are increased [5,9]. PD-1, which can be identified by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry, is related to lymphocyte apoptosis pathways and, therefore, is a possible therapeutic target [7,26]. CD158k consists of a receptor that, when activated, promotes an anti-apoptotic state in the cell and is an important marker of SS [7].

Vimentin, in turn, is a component of the cytoskeleton that is expressed both in normal T lymphocytes in activation and CS [7]. Both the CTLA4 / CD152 antigen and the transmembrane receptor Syndecan-4 (SD-4) have their expression greatly increased in SS, in the vast majority of cases [7,26].

Flow cytometry

It allows the absolute counting of Sézary cells in the blood more consistently, since the count by analysis of peripheral blood varies greatly from one observer to another [18]. It is worth noting that this method has limitations in this exact count, since not all atypical lymphocytes have the same phenotypic pattern. Flow cytometry can determine which lymphocyte antigens have their levels reduced or absent and, therefore, is used as a diagnostic criterion to determine the CD4/CD8 ratio [18].

According to Boonk et. al [23] evaluated the role of flow cytometry in the diagnosis of SS. 59 cases were studied, among the majority of patients had a CD4 / CD8 ratio >10, as well as the majority obtained an absolute CS count >1000 cells/mm3, including all those that did not meet the CD4/CD8 ratio criterion. Thus, it is evident the need to comply with several criteria for the correct diagnostic definition. Besides, more than 80% of the cases had a reduction in the expression of CD26, a proteolytic enzyme, just as there is usually a loss in the levels of CD7 in up to 70% of the CS in the syndrome are configured as highly sensitive markers and with a specificity still greater for the syndrome [7,9,21,23]. Among these two surface markers, the loss in CD26 expression is even more specific for the identification of SC, being important to exclude benign inflammatory dermatoses, which also have changes in CD7 expression [9]. When CS have a negative CD26 phenotype, they can proliferate in the skin and peripheral blood, since this enzyme is related to the regulation of cell activation [7].

The SC are not configured as a pathognomonic factor of the syndrome, considering that they can be found in the peripheral blood of a patient with benign conditions, for example benign dermatoses [3,21].

Seric markers

Proteins and other serum markers are not used for diagnosis, due to their low specificity. Among the possible markers, there is an increase in the levels of the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), related to more advanced stages of the syndrome, in addition to serum elevation of IgE and beta-2 microglobulin [26].

Leukogram

The SS is characterized by lymphopenia, eosinophilia. Severe cytopenias indicate bone marrow involvement by SC. Low TCD8 lymphocyte count, which further increases the CD4/CD8 ratio, contributing to a worse prognosis [26].

Differential diagnosis

It is extremely important to pay attention to the possible differential diagnoses of SS, mainly mycosis fungoides, in addition to other dermatoses that can cause erythroderma, such as psoriasis, chronic eczema, atopic dermatitis, leprosy and lichenoid pityriasis [4,19]. These possible diagnoses can involve both benign conditions, for example, hives, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, and malignant conditions, such as acute or chronic leukemia, among other components of LCCT [17].

Conclusion

Sézary's Syndrome is a rare and aggressive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, still challenging for the clinician and the dermatopathologist. We present a literature review of the natural history, clinical findings, the main diagnostic tools and its advances made by the last 10 years. Besides these advances, more studies are needed to proof the efficiency of the new markers. Also, we highlight the importance of the association between the many possible clinical manifestations and the laboratory findings, since these isolated criteria are not sufficient for the syndrome’s diagnosis.

References

2. Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. American Journal of Hematology. 2017 Oct;92(10):1085-102.

3. Foss FM, Girardi M. Mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Hematology/Oncology Clinics. 2017 Apr 1;31(2):297-315.

4. Vakiti A, Padala SA, Singh D. Sezary Syndrome. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Apr 28. StatPearls Publishing.

5. Kohnken R, Fabbro S, Hastings J, Porcu P, Mishra A. Sézary syndrome: clinical and biological aspects. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 2016 Dec 1;11(6):468-79.

6. Spicknall KE. Sezary syndrome-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018 Mar 1;37(1):18-23.

7. Cristofoletti C, Narducci MG, Russo G. Sézary syndrome, recent biomarkers and new drugs. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb 1;8(1):2.

8. Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: an update. Hematology/Oncology Clinics. 2019 Feb 1;33(1):103-20.

9. Martinez XU, Di Raimondo C, Abdulla FR, Zain J, Rosen ST, Querfeld C. Leukaemic variants of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Erythrodermic mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2019 Sep 1;32(3):239-52.

10. Mangold AR, Thompson AK, Davis MD, Saulite I, Cozzio A, Guenova E, et al. Early clinical manifestations of Sezary syndrome: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017 Oct 1;77(4):719-27.

11. Henn A, Michel L, Fite C, Deschamps L, Ortonne N, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Sézary syndrome without erythroderma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Jun 1;72(6):1003-9.

12. Thompson AK, Killian JM, Weaver AL, Pittelkow MR, Davis MD. Sézary syndrome without erythroderma: a review of 16 cases at Mayo Clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017 Apr 1;76(4):683-8.

13. Non-Classic Signs of Sézary Syndrome: A Review. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [citado 23 de abril de 2020]. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31953789

14. Damasco FM, Geskin LJ, Akilov OE. Nail changes in Sezary syndrome: a single-center study and review of the literature. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2019 Jul;23(4):380-7.

15. Park K, Reed J, Talpur R, Duvic M. Nail irregularities associated with Sezary syndrome. Cutis. 2019 Apr 1;103(4):E11-6.

16. Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, Burg G, Duvic M, Heald P, Laroche L, et al. Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002 Jan 1;46(1):95-106.

17. Kubica AW, Pittelkow MR. Sézary Syndrome. Surg Pathol Clin. junho de 2014;7(2):191–202.

18. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Feb 1;70(2):205-e1.

19. Klemke CD, Booken N, Weiss C, Nicolay JP, Goerdt S, Felcht M, et al. Histopathological and immunophenotypical criteria for the diagnosis of Sézary syndrome in differentiation from other erythrodermic skin diseases: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force Study of 97 cases. British Journal of Dermatology. 2015 Jul;173(1):93-105

20. Yamashita T, Abbade LP, Marques ME, Marques SA. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2012 Dec;87(6):817-30.

21. Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk‐stratification, and management. American Journal of Hematology. 2019 Sep;94(9):1027-41.

22. Olek-Hrab K, Silny W. Diagnostics in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Reports of Practical Oncology & Radiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;19(2):72-6.

23. Boonk SE, Zoutman WH, Marie-Cardine A, van der Fits L, Out-Luiting JJ, Mitchell TJ,. Evaluation of immunophenotypic and molecular biomarkers for Sezary syndrome using standard operating procedures: a multicenter study of 59 patients. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016 Jul 1;136(7):1364-72.

24. Clinical and Histological Characteristics of Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: A Retrospective, Single-centre Study of 43 Patients from Eastern Denmark [Internet]. [citado 31 de maio de 2020]. Disponível em: http://www.medicaljournals.se/acta/content/abstract/10.2340/00015555-3351

25. Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007 Sep 15;110(6):1713-22.

26. Dulmage B, Geskin L, Guitart J, Akilov OE. The biomarker landscape in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Experimental Dermatology. 2017 Aug;26(8):668-76.