Abstract

Over the past fifty years the somatic mutation theory of cancer has emerged as the most successful explanation of the molecular phenotype of human cancer cells. Normal non-mutated genes may, however, also play a role in carcinogenesis. In particular these may contribute to aerobic glycolysis and the potential interaction of PKM2 and Cdk4 in helping the nascent cancer cell avoid apoptosis by the interaction of their respective amino acid sequences: anionic SDPTEA and cationic PRGPRP. It is proposed that cancer first occurs in normal tissues cells which, as part of the premalignant phenotype have switched from PKM1 to PKM2 expression, and this phenotype persists as cancers age and further molecular biological mechanisms to avoid apoptosis and encourage aerobic glycolysis emerge. PRGPRP and several congeners have been shown to kill a wide range of in vitro cancers by necrosis by producing a fall in ATP without harming normal diploid cells. The ATP depletion is suggested to result from inhibition of aerobic glycolysis and has resulted in the first therapeutic agent that globally selectively kills cancer cells by depriving them of energy.

Keywords

Aerobic glycolysis, Cdk4, Apoptosis, Necrosis, Spontaneous cancer cell death

Introduction

At present, apart from surgery, the clinical treatment of cancer can essentially be described by three therapeutic strategies: attacking its growth by chemotherapy and or radiotherapy, blocking hormone stimulation of its growth as in breast and prostate cancer, and attempting to enhance natural immune recognition and rejection of the cancer. A possible fourth therapeutic strategy whose clinical application could considerably strengthen the present cancer therapeutic armamentarium is presented here based on studies of previously unexplored interrelationships between apparently disparate processes within the molecular components of the cancer cell phenotype. These include different modes of cancer cell death; cell cycle control of the G1/S transition; and aerobic glycolysis. Exploitation of the new paradigm has led to the development of a novel type of therapeutic which selectively kills cancer but not normal cells by depleting the cancer cell of energy rather than by attacking its proliferation.

The Molecular Biology of Oncogenesis

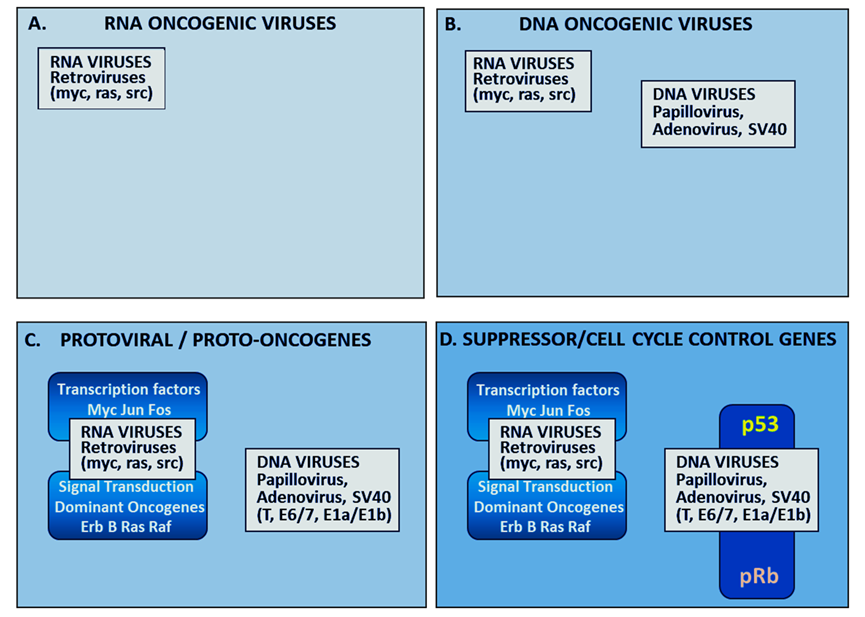

The evolution of an understanding of the molecular mechanisms that promote malignant transformation from a normal cell to a cancer cell was obscured for many years by the confusing multiplicity of apparently very different carcinogenic agents. Chemical carcinogenesis in chimney sweeping boys had been known since first described by Percival Pott in 1775. The first carcinogenic virus, src, was an RNA virus discovered in rat sarcomas by Peyton Rous in 1911 (Figure 1A) [1]. Three years later, Theodor Boveri proposed a somatic mutation theory of cancer based on his observations of chromosomal abnormalities [2]. The strong association between smoking carcinogenic tobacco and lung cancer, revealed by Doll and Hill in an epidemiolocal study in 1950 [3], strengthened the role of chemical carcinogenesis. In the 1950s and early 1960s, in addition to RNA viruses, certain DNA adenoviruses and polyoma viruses were found to cause cancer in animals (Figure 1B). Between 1965 and 1969, Dulbecco began the unravelling of the molecular mechanisms of malignant transformation by the sv40 polyoma virus [4]. In 1975 Zur Haussman identified the human papilloma, DNA, virus as a cause of cancer of the human uterine cervix [5]. Early in the twentieth century, two years after the discovery that an RNA virus could cause cancer, Otto Friedrich Warburg had contributed the important observation that carbohydrate metabolism in cancer cells was different from that in normal cells [6]. This phenomenon although initially considered to be of little significance came to be termed aerobic glycolysis and has acquired increasing importance in recent years.

Figure1.Schematic representation of the evolution of understanding of the molecular biology of cancer. The first RNA oncovirus was discovered by Peyton Rous in 1911 (Panel A). Oncogenesis by DNA adenoviruses and polyoma virus causing cancer in animals were discovered in the 1950s (Panel B). In the 1970s and early 1980s, RNA viruses were shown to parallel the activity of mutated somatic oncogenes causing autonomous upregulation of somatic signal transduction and transcription factors (Panel C). The action of oncogenic DNA viral antigens: papilloma E7, SV40 T and adenoviral E1Aa/E1b in blocking p53 and pRb tumour suppressor genes (Panel D) has been reviewed by Weinberg in 1994 [18].

The significance of the earlier discoveries of RNA viral oncogenesis were amplified by the work of Howard Temin (1971) who made the proposal in his proviral theory (considered heretical by some at the time) that viral oncogenic RNA genes were transcribed into DNA which was incorporated into the host genome. Temin [7] and Baltimore [8] discovered the enzyme reverse transcriptase which enabled Temin’s hypothesis and subsequently became an extremely useful molecular biology reagent. It was then demonstrated that human DNA somatic transforming oncogenes were homologous to viral RNA oncogenes [9,10] (Figure 1C). Understanding the way DNA viruses caused cancer was not as straightforward as for RNA oncoviruses but led indirectly to the discovery of the tumour suppressor gene, p53, when it was shown that the T transforming antigen of the sv40 virus operated by binding to and inhibiting the activity of p53 [11,12] which functions primarily as a transcription factor regulating a wide variety of pathways, such as cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, cell apoptosis, autophagy, and metabolism [13,14].

The discovery of the tumour suppressing retinoblastoma gene exemplified the somatic mutation theory of cancer. Fungus haematodes, a tumour that resembled retinoblastoma was described by Pieter Pawius of Amsterdam in 1597 [15] and the term retinoblastoma was approved by the American Ophthalmological Society in 1926. Knudsen proposed in 1971 that retinoblastoma was inherited as an autosomal recessive gene and the adult disease required two hits, either expression of two alleles of the inherited gene at birth or expression of the inherited allele plus mutation in the second allele after birth [16]. The structure of the human retinoblastoma gene was reported in 1989 [17].

The Gateway to Cell Division

The Rb and p53 suppressor proteins were envisaged as together providing the gateway to cell division and could be disabled by sv40, adenovirus and papilloma DNA viruses or by a wide number of somatic mutations (Figure 1D). The realisation, that the molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis initially discovered by studies of oncogenic viruses could also be the result of somatic mutations unified the paradigms of viral oncogenesis and somatic mutation [18]. The model that emerged was that the relentless unrestrained proliferation of cancer cells could be caused by viral oncogenes and/or by somatic mutations. Both resulted in upregulation of signal transduction or transcription factors and disabling of suppressor genes. Weinberg experimentally confirmed the somatic mutation theory of cancer by demonstrating the malignant transformation of normal mouse MRC 5 fibroblasts by DNA from rat and mouse carcinogen-induced cancers [19]. He later provided an analogy describing the somatic mutation model of cancer as being like an out of control car with the accelerator jammed on and the brakes disabled [20].

The somatic mutation theory is now widely accepted as providing the essential cancer paradigm. Further to this theory, however, a potential role for normal non-mutated genes in carcinogenesis [21,22] has been suggested.

Cancer Cell Death

Cancer cells are generally understood to be immortal [23] but observations of cancer regression in the clinic and spontaneous cancer cell death of single cancer cells growing under optimal conditions in tissue culture, [24], challenges this proposition.

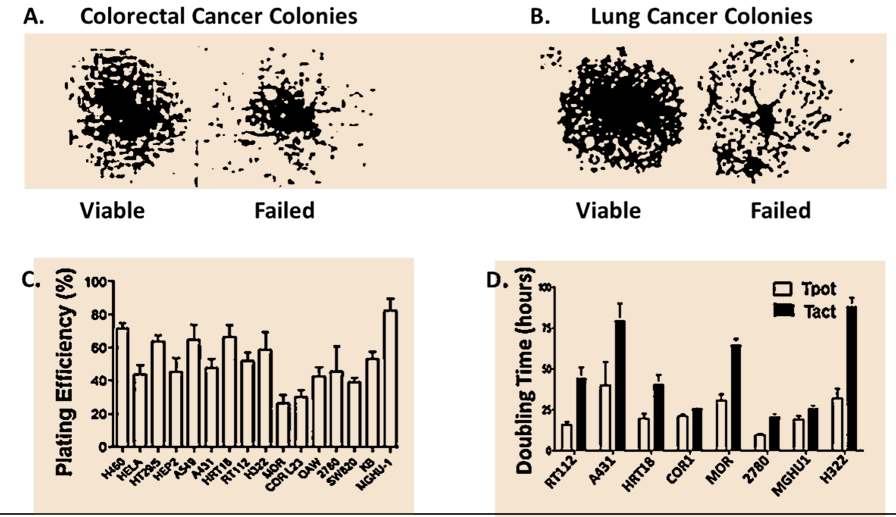

Figure 2 illustrates the spontaneous disintegration of colonies derived from single cells in untreated control clonogenic assays of SW620, colorectal, and H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells (Panels A and B respectively). Spontaneous death in colonies of untreated cancer cells was confirmed by failures in plating efficiencies of 20-70% in 16 different human in vitro cell lines (Panel C) and flow cytometric studies of potential and actual doubling times which showed that potential doubling time was always greater than actual doubling time in each of 8 human cancer cell lines (Panel D).

Figure 2. In vitro studies showing spontaneous cell death of untreated control cultures of Human Cancer Cells. Composite slide from previously published data [24]. Panels A and B show aborted colonies adjacent to successful viable colonies in untreated cultures of the SW20 colorectal and H460 non-small cell lung cancers grown under optimal tissue culture conditions at 15 days after plating single cell suspensions. Panel C. The plating efficiencies of 16 untreated cultures (H460, HELA, HT29/5, HEP2, A519, A431, HRT18, RT112, H322, MOR, COR-L23, OAW, 2780, SW620, KB, MGHU1) yield plating efficiencies between 30% and 80% (means + SE). The morphological appearances of dying cells were not consistent with apoptosis and were related to a change in the ratio of Cdk4 to Cdk1. Panel D. Spontaneous cancer cell death confirmed by flow cytometric comparison of potential and actual doubling times in eight of human cancer cell lines.

The phenomenon of spontaneous cancer cell death indicates that the molecular biological changes within a normal cell which by somatic mutation transform it into a cancer cell are not sufficient in themselves to guarantee the immortality of the transformed cell. This first became apparent in experiments by Gerard Evan at the close of the last century in studies of oncogenic transformation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts [25]. Attempts to transform normal cells into cancer cells using an upregulated Myc oncogene could either result in increased cell division or in apoptosis. Gerard Evan suggested that proliferation and apoptosis might be two opposing processes that Myc concurrently commandeered in cells. He suggested that apoptosis was a potential ‘abort’ programme in case proliferation went wrong [26].

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that the transformed cancer cell must avoid if it is to continue to successfully proliferate and spread [27]. Because apoptosis is an energy dependent process, the relative availability of ATP can determine whether or not apoptosis occurs in a normal cell undergoing malignant transformation. High levels of ATP enable cells to undergo apoptosis, low levels of ATP shift cells away from apoptosis towards necrosis [28]. Cancer cells navigate a narrow path between the Scylla of apoptosis and the Charybdis of necrosis. Levels of ATP which determine the choice between necrosis or apoptosis in normal cells have been shown to be influenced by the extent to which ATP is consumed by PARP activity, [29] so that, for example, fibroblasts from PARP deficient (PARP_/_) mice are protected from necrotic death and ATP-depletion but can still undergo apoptosis.

Cyclin Dependent Kinase 4

Weinberg’s analogy of a “cancer car” with the brakes disabled and the accelerator jammed on, needs a ” motor” if it is to be able to career dangerously forwards in the way cancer dangerously grows and spreads. The motor is provided by the cell cycle engine which arose from the discovery by Lee Hartwell in 1971 of CDC (cell division cycle) genes by detailed studies of temperature sensitive mutations in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. [30]. One of these, CDC28, he called START because he believed it was responsible for initiating cell division. Paul Nurse starting with an analogous gene, cdc2, in a different yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, showed by partial cloning and complementation studies that the yeast gene shared its activity with CDK (Cyclin Dependent Kinase) in human cells [31,32]. Cyclin dependent kinases were shown to be evolutionary conserved ubiquitous cell cycle control genes in eukaryotic cells both in single celled yeasts and multicellular organisms. The human analogue of CDK was CDK1 whose protein product (Cdk1) acted as a holoenzyme, when in combination with Cyclin B, to control exit from the cell cycle via mitosis.

In yeast Cdk1 is sufficient for the control of all phases of the cell cycle and there is evidence that Cdk1 can also operate in a similar manner in CDK2 null mammalian cells [33]. In multicellular organisms, however, further CDK closely related genes, in combination with different cyclins, are generally understood to sequentially control distinct transitions, known as checkpoints, between the different phases of the cell cycle [34]. The G1/S checkpoint is understood to be controlled by Cdk2/cyclin E, but the earliest checkpoint is Cdk4/cyclin D (or Cdk6/cyclin D) [35]. These cyclin dependent kinase/cyclin holoenzymes phosphorylate the retinoblastoma and related proteins causing the release of E2F and related factors which upregulate Cdk2/cyclin E and initiate transcription of proteins such as DNA polymerase and the multitude of enzymes required for DNA synthesis. The successful crystallisation of the Cdk4/cyclin D complex enabled the development of the kinase inhibitor abemaciclib, which binds in the ATP pocket of Cdk4 within the holoenzyme [36] The closely related selective Cdk4 kinase inhibitor, palbociclib, is at present used clinically to treat hormone positive advanced stage breast cancer [37].

Non Canonical Behaviour of CDK4

Gene knockdown experiments in mice, however, suggest that, as well as its canonical activity acting as a kinase within a holoenzyme, Cdk4 on its own possesses a non-canonical activity relevant to carcinogenesis and unrelated to its classical interaction with cyclin D. In 2002 Rodriguez-Puebla reported that Cdk4 deficiency, in gene knockout mice, inhibited methylcholanthrene induced skin tumor development after topical treatment with the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) but did not affect normal keratinocyte proliferation [38]. Using the same chemical carcinogenic experimental system Rodriguez-Puebla then showed that Cyclin D1 overexpression in mouse epidermis increased cyclin-dependent kinase activity and cell proliferation in vivo but did not influence skin tumor development [39]. Moreover, although cyclin D knockdown could diminish the incidence of Ras-induced tumours, it did not, in contrast to Cdk4, completely abrogate the development of cancer [40].

In these experiments it was the normal wild-type CDK4 gene on its own that was knocked down while cyclin D was untouched. As was first suggested by Warenius in 2002, the activity of normal non-mutated genes might be a necessary component of the carcinogenic process [21]. As well as preventing carcinogen induced cancer in mouse skin, the absence of Cdk4 also prevented oncogene-induced carcinogenesis. de Marval et al. reported that lack of CDK4 expression due to gene knockdown in K5Myc transgenic mice resulted in the complete inhibition of tumour development, induced by deregulated Myc, indicating that CDK4 is a critical mediator of oncogene promoted tumour formation [41]. In addition, in vitro transformation in response to Ras activation with dominant-negative (DN) p53 expression or in an Ink4a/Arf-null background does not occur in CDK4-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts, providing further evidence that Cdk4 is essential for immortalisation [42]. Furthermore, CDK4 knockdown inhibits the onset and incidence of mammary carcinoma in MMTV-Neu-Cdk4_/_ mice [43]. These examples of Cdk4 acting alone during carcinogenesis are consistent with the malignant transformation study reported by Sato in which human Cdk4 and telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) are required as the starting point for the stepwise transformation of normal human bronchial epithelium to lung cancer in early carcinogenesis [44].

Co-Expression of Cdk4 and Cdk1 in Human Cancer Cells

As well as its non-canonical role in carcinogenesis, Cdk4 also behaves differently from its closely related G1/S phase partners Cdk6 and Cdk2 in their comparative proteomic co-relationship with Cdk1 in human cancer cell lines.

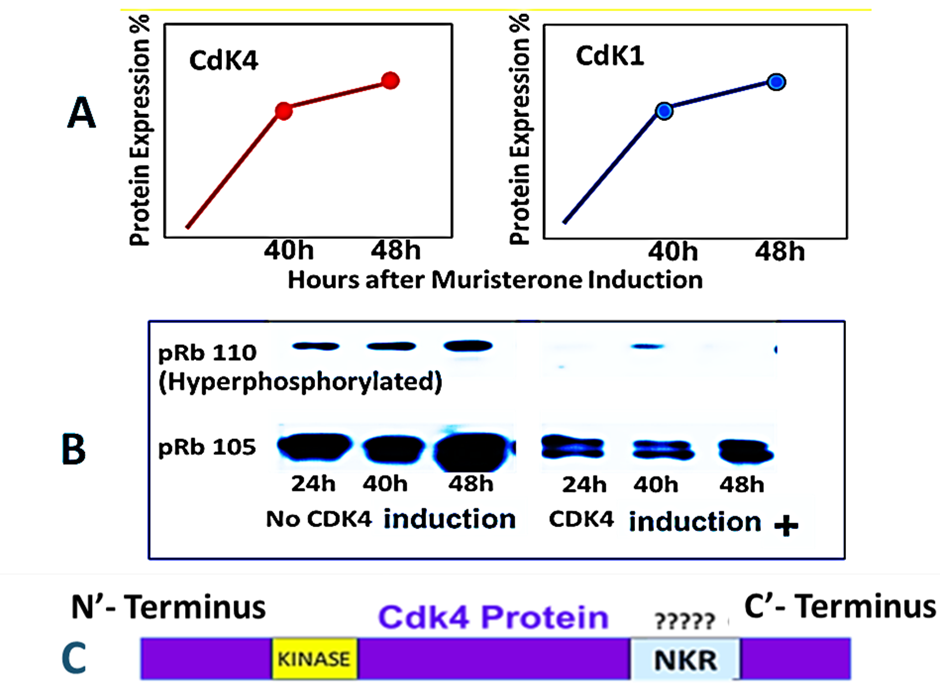

Seabra identified a co-relationship between Cdk1 and Cdk4 protein expression in human cancer cell lines that is not present in normal human diploid cells grown in short term culture [45]. Cdk6 and Cdk2 do not show a similar relationship [46]. Despite variations in absolute levels the significant co-relationship of Cdk4 and Cdk1 was consistently found through 12 serial passages of 19 human cancer lines [47] but was reversed in spontaneously dying untreated COR L-23 human non-small cell lung cancer [21]. Transfection of wild type CDK4 DNA in 2780 human ovarian cancer cells has been shown to not only upregulate Cdk4 but also to contemporaneously upregulate Cdk1 (Figure 3A) [46] without phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein occurring (Figure 3B). This suggested that Cdk4 might possess a non-kinase function as well as its canonical kinase activity. The kinase region and all associated functional regions of Cdk4 lie in the N’-terminal 2/3 of the protein. A search for a potential non-kinase functional region (NKR) was therefore made by comparing the amino acid sequences of the C’-terminal region (Figure 3C) with that of the closely related Cdk6 and Cdk2 proteins. This revealed an outside loop with the unique amino acid sequence FPPRGPRPVQ.

Figure 3. Cdk4 transfection of 2780 human ovarian cancer cells cause co-elevation of Cdk1 without retinoblastoma phosphorylation suggesting a possible non-kinase functional region in Cdk4. Composite data from Warenius et al. [46]. Panel A: Endogenous Cdk1 follows a similar time course and increase in proteomic expression as exogenous Cdk4 induced by 1 μM muristerone in 2780 pvrg-pINDK4 clone 1D cells. Panel B. Western blotting for total retinoblastoma protein (pRb 105) and hyperphosphorylated retinoblastoma protein (p110) following exposure of 2780 pvrgpINDK4 clone 1D cells to 1 μM muristerone. Panel C. Schematic presentation of originally proposed functional non-kinase region (NKR) unique to Cdk4.

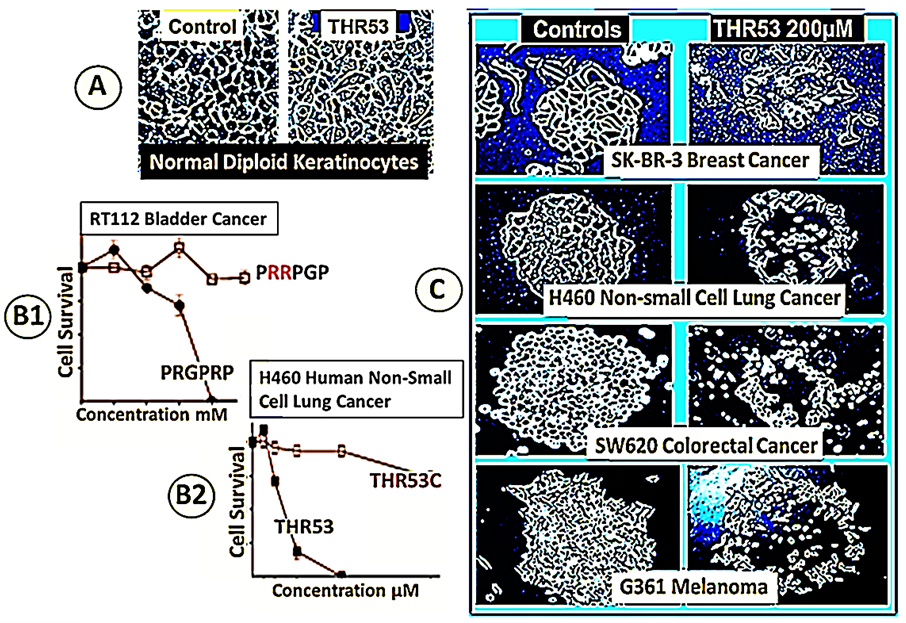

The central hexapeptide of this sequence was the linear peptide PRGPRP, which when synthesised linked to an amphiphilic cassette within a cyclic peptide (THR53), killed several human cancers of different histological subtypes by necrosis (Figure 4C) accompanied by a fall in intracellular ATP levels.

Changing the PRGPRP sequence to PRRPGP (Figure 4 B1, B2) completely removed the cytotoxicity and the drop in ATP. The dying morphological appearance of the different histological types of human cancer cells was similar and resembled that seen in human cancers undergoing spontaneous cancer cell death. Normal keratinocytes were unaffected by THR53 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Comparative effects of PRGPRP and THR53 on human cancer cell lines of different histological subtypes in human in vitro cancer cell lines compared to normal diploid human keratinocytes. Panel A. Primary cultures of explanted human keratinocytes with and without exposure to THR53. Panel B. Cancer cell necrosis following exposure to PRGPRP and THR53 does not occur when the relative positions of the arginines is altered as in PRRPGP and THR53C. Panel C. Different histological types of cancer die with closely similar morphological appearances after exposure to the same dose of THR53. Composite presentation from data described in Warenius et al. [46].

Aerobic Glycolysis

Following the observation by Warburg in 1927 that cancer cells had increased glucose uptake [6], the idea that oncogenesis could be related to altered carbohydrate metabolism was not met with enthusiasm and was outcompeted by research into viral and chemical carcinogenesis and somatic mutation. Slowly, however, interest has increased in the phenomenon of aerobic glycolysis, in which cancer cells selectively use only the glycolytic component of the glucose catabolism pathway without the mitochondria, despite sufficient availability of oxygen [48]. A widespread belief that the Warburg effect was simply the consequence of hypoxia in cancer cells has not been supported by the finding that aerobic glycolysis has been found in the absence of hypoxia in normal adult tissues such as activated T cells [49] and in norrmoxic precancerous regions of cancers of the cervix [50] and rectum [51]. An illustration of Warburg’s early observation of increased glucose uptake by cancer cells is exemplified by the technology used by PET scans which identify clinical cancers by their accumulation of deoxy glucose labelled with the positron emitter 18F [52].

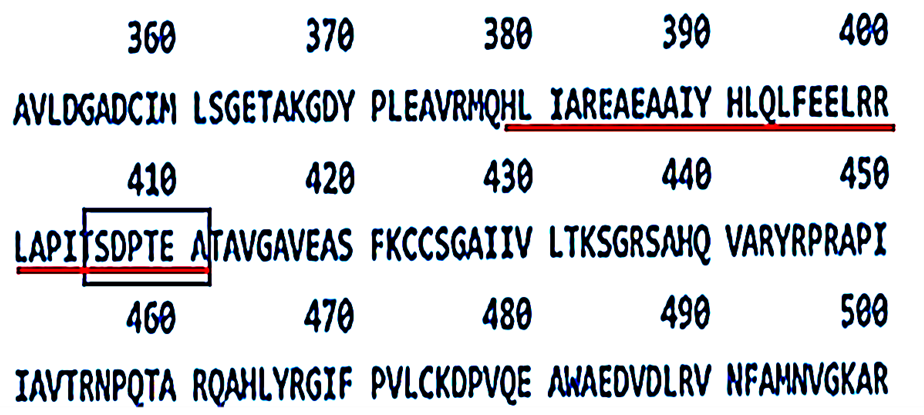

The mechanism of Warburg’s hypothesis can now be explained by the expression of the PKM2 isoform of the pyruvate kinase gene rather than the PKM1 isoform because of a switch to exon 10 rather than exon 9 [53]. This results in a different amino acid sequence to that of PKM1, between residues 378 and 411 underlined in red in figure 5 and unique to adult human cancer cells in contrast to normal cells which express the PKM1 isoform.

Figure 5.Linear amino acid sequence of the tetramerisation region of Pyruvate Kinase M2. The amino acid sequence of the peptide region contained within the tetramerisation interface between amino acid residues 378 and 411 is underlined in red. SDPTEA, the putative target for PRGPRP at amino acid residues 406 -411, is included by the rectangular box. Data extracted from the UniProt Blast (TrEMBL) amino-acid sequence of human PKM2.

The expression of the PKM2 rather than the PKM1 isotype of the PKM gene creates the aerobic glycolysis switch site where pyruvate created by dephosphorylation of phospho-enol pyruvate, at the end of the glycolytic pathway, is normally directed by PKM1 in non-cancerous adult cells into mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. In cancer cells PKM2 causes pyruvate to remain outside the mitochondria being converted instead to lactate.

Warburg proposed that dysfunctional mitochondria is the root cause of aerobic glycolysis and further hypothesised that this event was the primary cause of cancer [54]. In addition, he suggested the “glycolytic phenotype” appears to confer emerging malignant cells with a selective advantage, which may help to explain in part why this metabolic strategy is commonly observed across tumours. It is now known that mitochondria are in fact dysfunctional in cancer. Mutations in mtDNA and decreased mtDNA copy number are frequently found in cancer cells and are believed to drive carcinogenesis, and driving effects of mtDNA mutations in carcinogenesis initiation have been clearly established by depleting cancer cell lines of mtDNA [55]. A definitive explanation for Warburg’s observation has, however, remained elusive because the energy requirements of cell proliferation appear to be better met by complete catabolism of glucose using mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to maximize adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) production [56]. Also, many studies have shown that contrary to appearances, mitochondria are functional in most cancer cells, actively contribute to carcinogenesis and tumor development, and are suggested as potential drug targets. [57]. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that a gain of function in oncogenes, loss or mutation of tumor suppressors, and the activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) are major regulators of the high levels of aerobic glycolysis observed in tumor cells [58]. These results partly supporting but mainly challenging Warburg’s hypothesis have been obtained in well-established cancer cells, however, whereas aerobic glycolysis can happen in normal cells and in premalignant tissues [49-51] before full transformation into cancer has occurred.

Putative Interaction of PKM2 and Cdk4 Could Avoid Apoptosis in the Initial Oncogenic Transformation of a Normal Cell to a Cancer Cell.

To explain the above paradox, it has been recently proposed that oncogenic transformation starts in a normal cell that expresses the PKM2 phenotype and that Cdk4, upregulated by an initial oncogenic somatic mutation, not only triggers cell division by the canonical pathway but at the same time down regulates PMK2 causing ATP to drop below the level at which apoptosis can occur [59]. The PKM2 phenotype of the originally transformed cancer cell would be likely to persist during subsequent generations. As the newly transformed cancer grows, the development of new oncogenes, disabled suppressor genes, and upregulated PI3K promote the aerobic glycolysis phenotype. This benefits biosynthesis of anabolic precursors required for cancer cell growth and proliferation, such as proteins and nucleotides [60]. Mitochondrial activity resumes in the original PKM2 cell which had undergone transformation producing much higher levels of ATP than provided by aerobic glycolysis. These would be expected to be high enough to trigger apoptosis, but the established cancer cell will have become able to avoid apoptosis more easily by increasing or decreasing the expression of anti- or pro- apoptotic genes, respectively or stabilising or de-stabilising anti- or pro-apoptotic proteins, respectively. In this way the original phenotypic requirement for the expression for PKM2 to interact with Cdk4 allowing the newly transformed cancer cell to avoid apoptosis by downregulating ATP is no longer an important operator in the increasingly complex heterogenous genetically unstable, ever evolving, cancer phenotype. Thus, rather than arising de novo after malignant transformation has already occurred the ubiquitous presence of aerobic glycolysis probably reflects the persistence of PKM2 expression present from the time of the preneoplastic cell in which the first somatic mutation happened. In a sense that he did not foresee, Warburg was right in claiming that the altered carbohydrate metabolism he observed was the primary cause of cancer because it set the scene for malignant transformation to come about. For successful initial malignant transformation of a normal cell into a cancer cell with the avoidance of apoptosis, the coincident occurrence of both oncogenic somatic mutation and aerobic glycolysis may be required.

Development of a Cancer Necrotising Therapeutic

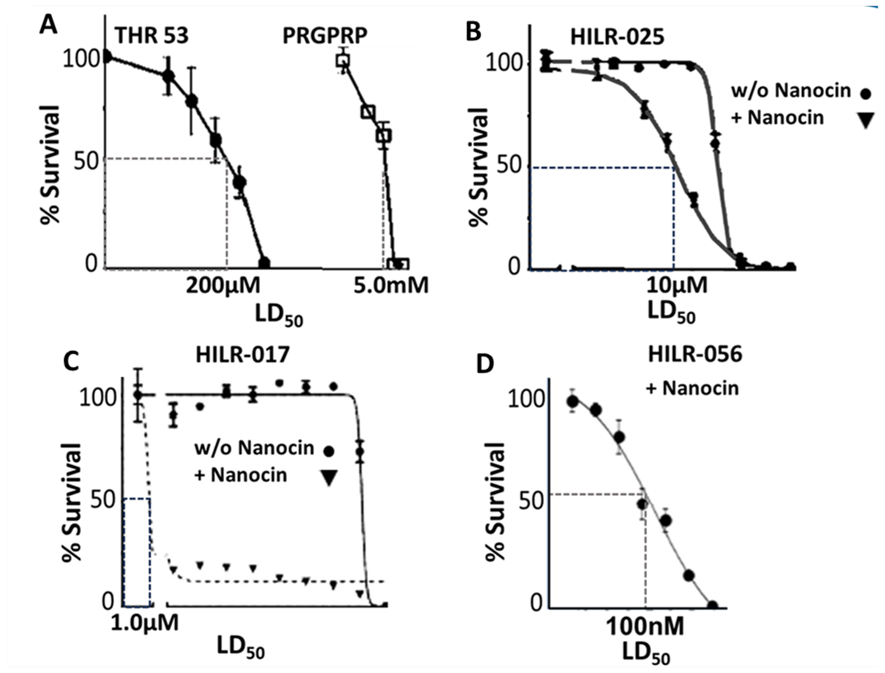

It has been hypothesised that the mechanism by which Cdk4 modulates ATP production by PKM2 is by interaction of the highly cationic PRGPRP hexapeptide, in an outside loop of the C’-terminal region of wild-type Cdk4, with the anionic SDPTEA sequence at the end of the PKM2 tetrameric interface (shown in box in Figure 5) [59]. PRGPRP in an amphiphilic cassette (THR53), had been shown to cause a wide range of different histological types of cancer to die by necrosis accompanied by a fall in intracellular ATP, without damage to normal fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Because the specific activity of 200 µM was too low for THR53 to be useful as an in vivo therapeutic agent, modifications to the PRGPRP analogous portion termed the warhead and to the amphiphilic region within the cyclic peptide termed the cassette have been made with the intention of improving specific activity (Figure 6). The optimal amphiphilic cassette was obtained with a duplex WWRR repeat as in HILR-025 with a twentyfold improved specific activity of 10 µM. The optimal warhead was produced by replacing the prolines with amino acids carrying highly hydrophobic naphthalene (Nap) and methoxy coumarin (Dac) side chains and replacing glycine with sarcosine yielding HILR-017 with an LD50 of 1.0µM. Combining the two modifications yielded HILR-056 with an LD50 of 100nM which is 5000 greater than the original PRGPRP and would be expected to be in the therapeutic range for effective in vivo activity in planned xenograft preclinical studies. After THR53 newer congeners were found to be increasingly insoluble as their hydrophobicity increased, requiring the commercial product Nanocin PRO (Tecrea Ltd London UK) as a solubilising agent. Early results (unpublished) show good in vitro activity of HILR-056 against SHSY5Y and IMR 32 neuroblastoma cell lines, widening the cytotoxic breadth of PRGPRP analogues to include paediatric as well as adult cancers.

Figure 6. Cell survival curves showing LD50 values for H460 human non-small cell lung cancer following exposure to PRGPRP and congeners of increasing specific activity. Panel A data from Warenius et al. [46]. Panels B and C unreported data published in EU granted patent 428998EP. Panel D. Previously unpublished data. Peptide structures: THR53: Cyc[Pro-Arg-Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro-Val-Ala-Leu-Lys-Ala-Leu-Lys-Ala-Leu] HILR-025: Cyc[Pro-Arg-Sar-Pro-Arg-Pro-Val-Tryp-Tryp-Arg-Arg-Tryp-Tryp-Arg-Arg Tryp-Tryp-Arg-Arg]; HILR-017: Cyc[Cys-Dac-Arg-Sar-Nap-Arg-Nap-clips-Cys] HILR-056: Cyc[CycDac-Arg-Sar-Nap-Arg-Na-Val-Tryp-Tryp-Arg-Arg-Tryp-Tryp-Arg-Arg].

The effectiveness of PRGPRP and its congeners in selectively killing a wide range of human cancers without affecting normal cells is unexpected in the context of a body of evidence indicating mitochondria still function in cancer cells and provide more ATP than PKM2. It would be expected that in this situation drugs which interact with the mechanism of aerobic glycolysis would have little impact on the global cellular ATP content. It is thus difficult to explain the observation that PRGPRP compounds can cause striking global selective cancer cell necrosis. The presence of spontaneous cancer cell death (discussed above) with similar morphological appearances to the death caused by PRGPRP and its congeners may indicate that despite the fact that mitochondria are active in cancer cells these cells are still operating at an energy deficit and so they remain vulnerable to relatively small downregulation of their energy levels. Alternatively, the SDPTEA amino acid sequence unique to PKM2 is closely similar to its analogous anionic sequence TDLMEA in PKM1 at the same site as SDPTEA, whose anionic aspartic and glutamic acid positioning might be expected to align in a similar manner with PRGPRP. Whether targeting TDLMEA in PKM1 would influence ATP production is not known to the author.

PKM2 has been cited as a potential target for cancer chemotherapy and Shikonin [61] and other agents reviewed by Rathod et al [62] have been investigated as potential candidates to target its activity. To date, however, to the author’s knowledge there are no known therapeutic agents that successfully target PKM2 tetramerisation. The chance finding of the novel hexapeptide PRGPRP within the non-kinase C’-terminal region of Cdk4, its potential ability to modulate PKM2 and the development from it of HILR-056 may provide the first example of a therapeutic that can selectively kill cancer by depriving it of energy rather than attacking its growth.

Funding

Personal.

Ethics

No ethical approval required.

Clinical Trials

None.

Data Availability

All data is in earlier literature and in patent applications.

References

2. Boveri T. Zur frage der entstehung maligner tumoren. Fischer; 1914.

3. Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report. British Medical Journal. 1950 Sep 30; 2(4682):739-48.

4. Dulbecco R. A consideration of virus-host relationship in virus-induced neoplasia at the cellular level. Cancer Research. 1960 Jun 1;20(5_Part_1):751-61.

5. zur Hausen H, Gissmann L, Steiner W, Dippold W, Dreger I. Human Papilloma Viruses and Cancer. Bibl Haematol. 1975 Oct:(43):569-71.

6. Warburg OH. Uber den heutigen Stand des Carcinomproblems. Naturwissenschaften. 1927;15(1):1-4.

7. Temin HM, editor. The protovirus hypothesis: speculations on the significance of RNA-directed DNA synthesis for normal development and for carcinogenesis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1971 Feb 1;46(2):III-VII.

8. Baltimore D. Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase: RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of RNA tumour viruses. Nature. 1970 Jun 27;226(5252):1209-11.

9. Chang EH, Furth ME, Scolnick EM, Lowy DR. Tumorigenic transformation of mammalian cells induced by a normal human gene homologous to the oncogene of Harvey murine sarcoma virus. Nature. 1982 Jun 10;297(5866):479-83.

10. Shimizu K, Goldfarb M, Suard Y, Perucho M, Li Y, Kamata T, Feramisco J, et al. Three human transforming genes are related to the viral ras oncogenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1983 Apr;80(8):2112-6.

11. Linzer DI, Levine AJ. Characterization of a 54K dalton cellular SV40 tumor antigen present in SV40-transformed cells and uninfected embryonal carcinoma cells. Cell. 1979 May 1;17(1):43-52.

12. Lane DP, Crawford LV. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SY40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979 Mar 15;278(5701):261-3.

13. Kastenhuber ER, Lowe SW. Putting p53 in context. Cell. 2017 Sep 7;170(6):1062-78.

14. Sullivan KD, Galbraith MD, Andrysik Z, Espinosa JM. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by p53. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2018 Jan;25(1):133-43.

15. Pawius P. Observatio XXIII. Tumor oculorum. Observationes Anatomicae Selectiores Appended to: Bartholinus T. Historiarum Anatomicarum Rariorum, Centuria III & IV. Copenhagen: Denmark Petrus Morsing.;1657.

16. Knudson Jr AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1971 Apr;68(4):820-3.

17. Hong FD, Huang HJ, To H, Young LJ, Oro A, Bookstein R, et al. Structure of the human retinoblastoma gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1989 Jul;86(14):5502-6.

18. Weinberg RA. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 1994 May;44(3):160-70.

19. Shih C, Shilo BZ, Goldfarb MP, Dannenberg A, Weinberg RA. Passage of phenotypes of chemically transformed cells via transfection of DNA and chromatin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1979 Nov;76(11):5714-8.

20. Weinberg RA, Robert A. The biology of cancer. ed. New York: Garland Science; 2014.

21. Warenius HM. Are critical normal gene products in cancer cells the real therapeutic targets?. Anticancer Research. 2002 Sep 1;22(5):2651-5.

22. Warenius HM. The essential molecular requirements for the transformation of normal cells into established cancer cells, with implications for a novel anti‐cancer agent. Cancer Reports. 2023 Jun 6:e1844.

23. Duesberg P, McCormack A. Immortality of cancers: a consequence of inherent karyotypic variations and selections for autonomy. Cell Cycle. 2013 Mar 1;12(5):783-802.

24. Warenius H, Kyritsi L, Grierson I, Howarth A, Seabra L, Jones M, et al. Spontaneous regression of human cancer cells in vitro: potential role of disruption of Cdk1/Cdk4 co-expression. Anticancer Research. 2009 Jun 1;29(6):1933-41.

25. Evan GI, Wyllie AH, Gilbert CS, Littlewood TD, Land H, Brooks M, et al. Induction of apoptosis in fibroblasts by c-myc protein. Cell. 1992 Apr 3;69(1):119-28.

26. Dhillon P, Evan G. In conversation with gerard evan. The FEBS Journal. 2019 Dec;286(24):4824-31.

27. Fernald K, Kurokawa M. Evading apoptosis in cancer. Trends in Cell Biology. 2013 Dec 1;23(12):620-33.

28. Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Research. 1997 May 15;57(10):1835-40.

29. Ha HC, Snyder SH. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase is a mediator of necrotic cell death by ATP depletion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999 Nov 23;96(24):13978-82.

30. Hereford LM, Hartwell LH. Sequential gene function in the initiation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA synthesis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1974 Apr 15;84(3):445-61.

31. Lee MG, Nurse P. Complementation used to clone a human homologue of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2. Nature. 1987 May 7;327(6117):31-5.

32. Nurse P. Finding CDK: linking yeast with humans. Nature Cell Biology. 2012 Aug 1;14(8):776.

33. Bashir T, Pagano M. Cdk1: the dominant sibling of Cdk2. Nature Cell Biology. 2005 Aug;7(8):779-81.

34. Graña X, Reddy EP. Cell cycle control in mammalian cells: role of cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), growth suppressor genes and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs). Oncogene. 1995 Jul 20;11(2):211-20.

35. Kim S, Leong A, Kim M, Yang HW. CDK4/6 initiates Rb inactivation and CDK2 activity coordinates cell-cycle commitment and G1/S transition. Scientific Reports. 2022 Oct 7;12(1):16810.

36. Gharbi SI, Pelletier LA, Espada A, Gutiérrez J, Sanfeliciano SM, Rauch CT, et al. Crystal structure of active CDK4-cyclin D and mechanistic basis for abemaciclib efficacy. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022 Nov 29;8(1):126.

37. Liu M, Liu H, Chen J. Mechanisms of the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD 0332991) and its future application in cancer treatment. Oncology Reports. 2018 Mar 1;39(3):901-11.

38. Rodriguez-Puebla ML, de Marval PL, LaCava M, Moons DS, Kiyokawa H, Conti CJ. Cdk4 deficiency inhibits skin tumor development but does not affect normal keratinocyte proliferation. The American Journal of Pathology. 2002 Aug 1;161(2):405-11.

39. Rodriguez-Puebla ML, LaCava M, Conti CJ. Cyclin D1 overexpression in mouse epidermis increases cyclin-dependent kinase activity and cell proliferation in vivo but does not affect skin tumor development. Cell Growth Differ 1999, 10:467-472.

40. Robles AI, Rodriguez-Puebla ML, Glick AB, Trempus C, Hansen L, Sicinski P, et al. Reduced skin tumor development in cyclin D1-deficient mice highlights the oncogenic ras pathway in vivo. Genes & Development. 1998 Aug 15;12(16):2469-74.

41. Miliani de Marval PL, Macias E, Rounbehler R, Sicinski P, Kiyokawa H, Johnson DG, et al. Lack of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 inhibits c-myc tumorigenic activities in epithelial tissues. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004 Sep 1;24(17):7538-47.

42. Zou X, Ray D, Aziyu A, Christov K, Boiko AD, Gudkov AV, et al. Cdk4 disruption renders primary mouse cells resistant to oncogenic transformation, leading to Arf/p53-independent senescence. Genes & Development. 2002 Nov 15;16(22):2923-34.

43. Baker SJ, Poulikakos PI, Irie HY, Parekh S, Reddy EP. CDK4: a master regulator of the cell cycle and its role in cancer. Genes & Cancer. 2022;13:21-45.

44. Sato M, Larsen JE, Lee W, Sun H, Shames DS, Dalvi MP, et al. Human lung epithelial cells progressed to malignancy through specific oncogenic manipulations. Molecular Cancer Research. 2013 Jun 1;11(6):638-50.

45. Seabra L, Warenius H. Proteomic co-expression of cyclin-dependent kinases 1 and 4 in human cancer cells. European Journal of Cancer. 2007 Jun 1;43(9):1483-92.

46. Warenius HM, Kilburn JD, Essex JW, Maurer RI, Blaydes JP, Agarwala U, et al. Selective anticancer activity of a hexapeptide with sequence homology to a non-kinase domain of Cyclin Dependent Kinase 4. Molecular Cancer. 2011 Dec;10(1):72-88.

47. Warenius H, Howarth A, Seabra L, Kyritsi L, Dormer R, Anandappa S, et al. Dynamic heterogeneity of proteomic expression in human cancer cells does not affect Cdk1/Cdk4 co-expression. Journal of Experimental Therapeutics & Oncology. 2008 Sep 1;7(3):237-54.

48. Weinhouse S. The Warburg hypothesis fifty years later. Zeitschrift für Krebsforschung und Klinische Onkologie. 1976 Jan;87:115-26.

49. Salmond RJ. mTOR regulation of glycolytic metabolism in T cells. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2018 Sep 25;6:122.

50. Chen X, Yi C, Yang MJ, Sun X, Liu X, Ma H, et al. Metabolomics study reveals the potential evidence of metabolic reprogramming towards the Warburg effect in precancerous lesions. Journal of Cancer. 2021;12(5):1563-74.

51. Cruz MD, Ledbetter S, Chowdhury S, Tiwari AK, Momi N, Wali RK, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of the premalignant colonic mucosa is an early event in carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2017 Mar 3;8(13):20543-57.

52. Czernin J, Phelps ME. Positron emission tomography scanning: current and future applications. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002 Feb;53(1):89-112.

53. Israelsen WJ, Vander Heiden MG. Pyruvate kinase: Function, regulation and role in cancer. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2015 Jul 1;43:43-51.

54. Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells?. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2016 Mar 1;41(3):211-8.

55. van Gisbergen MW, Voets AM, Starmans MH, de Coo IF, Yadak R, Hoffmann RF, et al. How do changes in the mtDNA and mitochondrial dysfunction influence cancer and cancer therapy? Challenges, opportunities and models. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2015 Apr 1;764:16-30.

56. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009 May 22;324(5930):1029-33.

57. Bedi M, Ray M, Ghosh A. Active mitochondrial respiration in cancer: a target for the drug. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2022 Feb 1:1-7.

58. Hoxhaj G, Manning BD. The PI3K–AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2020 Feb;20(2):74-88.

59. Warenius HM. The essential molecular requirements for the transformation of normal cells into established cancer cells, with implications for a novel anti‐cancer agent. Cancer Reports. 2023 Jun 6:e1844.

60. Sciacovelli M, Gaude E, Hilvo M, Frezza C. The metabolic alterations of cancer cells. Methods in Enzymology. 2014 Jan 1;542:1-23.

61. Sun Q, Gong T, Liu M, Ren S, Yang H, Zeng S, et al. Shikonin, a naphthalene ingredient: Therapeutic actions, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, clinical trials and pharmaceutical researches. Phytomedicine. 2022 Jan 1;94:153805.

62. Rathod B, Chak S, Patel S, Shard A. Tumor pyruvate kinase M2 modulators: A comprehensive account of activators and inhibitors as anticancer agents. RSC Medicinal Chemistry. 2021;12(7):1121-41.