Abstract

Rickets, a metabolic disease restricted to an age group before epiphyseal growth plate fusion, and is diagnosed by typical skeletal deformities and characteristic radiological features. The commonest etiology of rickets worldwide is nutritional deficiency of vitamin D and/or calcium, followed by primary renal phosphate wasting disorders. Renal tubular acidosis is an important cause of rickets, particularly ‘resistant rickets’, as the diagnosis is often missed initially and the patients are being wrongly treated with other agents without any benefit. Renal tubular acidosis is characterized by normal anion gap metabolic acidosis and is classified into different subtypes. A systemic step-wise approach is needed in suspected patients to unveil the subtype of renal tubular acidosis and the underlying etiology. Early diagnosis and proper management of renal tubular acidosis leads to complete clinical and radiological recovery in patients presenting with rickets secondary to renal tubular acidosis.

Keywords

Rickets, Renal tubular acidosis, Urinary anion gap, Tubular reabsorption of phosphate, Tubular maximum for phosphate corrected for GFR

Introduction

Rickets, a skeletal disorder limited to children and adolescents before epiphyseal fusion, and is characterized by deficient mineralization of the growth plate cartilages. Children with rickets display typical skeletal deformities and radiological abnormalities, and, these features are also associated with defective mineralization of mature osseous matrix, a condition known as osteomalacia. Normal mineralization of either the cartilages or the lamellar bone requires optimal calcium X phosphate product, which in turn depends on a homeostatic system, finely regulated by vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH). Three principal metabolic abnormalities found in overwhelming majority of children with rickets are defective vitamin D homeostasis (deficiency, metabolism, and action), primary renal phosphate wasting, and calcium deficiency; hence rickets are often broadly classified as calciopenic rickets and phosphopenic rickets. While calciopenic rickets is secondary to calcium deficiency or altered vitamin D homeostasis, phosphopenic rickets is the result of primary renal phosphate wasting, and is typically characterized by normal serum calcium and PTH [1,2]. However, it needs to be remembered that all forms of calciopenic rickets are associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism and resultant hypophosphatemia due to PTH induced proximal renal tubular loss of phosphate. Hypophosphatemia, seen both in calciopenic and phosphopenic rickets, interferes with capase-9 mediated apoptosis of the hypertrophic chondrocytes, that ultimately gives rise to the typical clinical and radiological appearances.

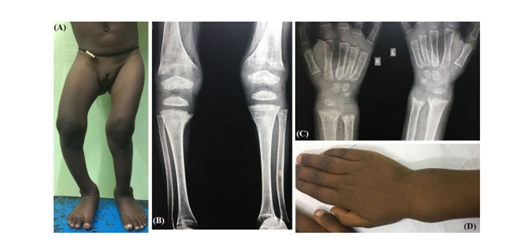

Hypophosphatasia, a condition associated with deficient function of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme, chronic systemic acidosis due to any cause, and drugs like bisphosphonate, fluoride, aluminium and parenteral iron are also associated with mineralization defects of the cartilages and bones. Serum calcium and phosphate concentrations are usually normal in rickets secondary to these conditions. Two most common disorders associated with metabolic acidosis and rickets are chronic kidney disease and renal tubular acidosis (RTA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 4-year girl with rickets due to dRTA. Note the ‘windswept’ deformity (A) and wrist widening (D). Typical radiological features like cupping, splaying, fraying and increased metaphyseal lucency are visible around knee (B) and wrist joints (C).

Renal Tubular Acidosis

RTA is a group of renal tubular disorders due to defects in proximal tubular reabsorption of bicarbonate ion (HCO3-), distal tubular excretion of hydrogen ion (H+) or both, and is characterized by hyperchloremic normal serum anion gap (AG) metabolic acidosis in patients with relatively normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Lost HCO3- in this condition is effectively replaced by chloride ion (Cl-), resulting in hyperchloremia and normal AG. Patients with estimated GFR (eGFR) between 20-50 ml/min/1.73M2 usually have normal AG, while those with eGFR of <20 ml/min/1.73M2 have high AG. Acid-base disequilibrium in RTA occurs despite a normal or only mildly reduced glomerular GFR [3]. RTA is a poorly appreciated entity among many physicians, and understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease is important for subtyping and appropriate management. It can be classified into three major forms: type 1 or distal RTA (dRTA), type 2 or proximal RTA (pRTA) and type 4 or hyperkalemic RTA. dRTA is associated with reduced H+ secretion, pRTA is characterized by impaired HCO3- reabsorption, and type 4 RTA is an acid-base disturbance generated by aldosterone deficiency or resistance. RTA can occur due to primary renal pathology or secondary to a variety of systemic diseases (Table 1).

|

|

Primary |

Secondary |

|

Distal RTA (type 1) |

Sporadic or Hereditary (Mutation of H+K+ATPase, H+ATPase, AE1) |

Autoimmune: Sjogren’s, SLE, RA, PBC Nephrotoxins: Amphotercicn B, Trimethoprim, lithium Miscellaneous: Sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, obstructive uropathy |

|

Proximal RTA (type 2) |

Sporadic or Hereditary (Mutation of CA-IV, NHE-3, NBC-1) |

Autoimmune: Sjogren’s Nephrotoxins: tetracycline, topiramate, valproate, acetazolamide Metabolic: Wilson’s disease, Cystinosis, Lowe’s syndrome, Galactosemia, chronic hypocalcemia; Hereditary fructose intolerance, Tyrosinemia Miscellaneous: Multiple myeloma, amyloidosis |

|

Hyperkalemic RTA (type 4) |

PHA-1, PHA-2 (Gordon’s syndrome)

|

Aldosterone deficiency or aldosterone resistance: Hypoaldosteronism, ACEIs, ARBs Hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism: Diabetes, Sickle cell disease Tubulointerstitial disease (eGFR: 20-50 ml/min) Drugs: Potassium sparing diuretics, NSAIDs, Trimethoprim, Pentamidine, Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus |

|

Mixed RTA (type 3) |

Mutation in CA-II |

Type 1 RTA with secondary proximal tubule dysfunction, Type 2 RTA with secondary distal tubule dysfunction |

|

AE1: Anion exchanger 1; CA: Carbonic anhydrase; NHE-3: Sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3; NBC-1: Sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter 1; PHA: Pseudo hypoaldosteronism; SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis; ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker |

||

Less than 1% of total H+ secreted from distal tubule remain as free H+; most protons are excreted as NH4+ (NH3+H+). dRTA is characterized by defective distal H+ secretion, hence less urinary NH4+ excretion; as a result, urine pH is >5.5, that is persistent and present during simultaneous systemic metabolic acidosis. Alkaline urine associated with hypercalciuria and hypocitraturia, often seen in dRTA, contribute to nephrocalcinosis and/or nephrolithiasis (Figure 2) [4]. Serum potassium (K+) is often low or normal, except when there is an underlying voltage-dependent defect, which is associated with impaired distal sodium (Na+) transport and secondary impairment of distal K+ secretion, leading to hyperkalemia (hyperkalemic dRTA) [5]. Hyperkalemic dRTA is different from type 4 RTA. In contrast to hyperkalemic dRTA, the ability to lower urine pH in response to systemic acidosis is maintained, and nephrocalcinosis is absent in type 4 RTA. Clinical manifestations in type 4 RTA are usually due to underlying disease, rather than RTA per se. An incomplete form of dRTA is often encountered, where patients demonstrate normal blood pH with low normal or mildly decreased serum HCO3- concentration, while lacking the ability to acidify urine when systemic acidosis is induced with an acidifying agent.

Figure 2: dRTA in a 16-year-old boy with rickets and bilateral nephrocalcinosis (C). Metaphyseal changes are seen in B.

Proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) reabsorbs 80–85% of the filtered HCO3-, 10% is from the loop of Henle and remaining 5–10% is reabsorbed from collecting tubules. pRTA is characterized by impaired HCO3- reabsorption from PCT, i.e. a decrease in renal HCO3- threshold to 14-18 mmol/L, which is normally ≈22 mmol/L in infants, and 25–26 mmol/L in children and adults [6]. Metabolic acidosis in pRTA tends to be milder because distal HCO3- reclamation remains intact and bicarbonaturia disappears when serum HCO3- concentration falls below the HCO3- tubular maximum (often at serum HCO3- level of 14-18 mmol/L). Urine pH in pRTA is variable; alkaline (>5.5), if serum HCO3- concentration is above the threshold, and <5.5 when serum HCO3- is below the threshold. pRTA may be isolated, or more commonly associated with Fanconi syndrome, a form of generalized proximal tubular dysfunction. Fanconi syndrome is a malabsorptive state of the PCT, wherein absorption of glucose, amino acids, low molecular weight proteins, phosphates, potassium, bicarbonate and uric acid are impaired; while pRTA refers to the deficiency in HCO3- retention only. Despite hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis/nephrolithiasis are infrequent, due to acidic urine and absence of hypocitraturia [7].

Type 3 RTA shares features of both type 1(dRTA) and 2 (pRTA). Carbonic anhydrase II (CA-II) deficiency, either inherited or acquired, presents with features of both pRTA and dRTA along with osteopetrosis, cerebral calcification and mental retardation due to deficiency of the enzymes in various organs [8]. Other conditions likely to be associated with type 3 RTA are acetazolamide use, Wilson disease, hereditary fructose intolerance and dysproteinemic syndromes. More commonly however, this pattern is observed as a transient phenomenon, when biochemical abnormalities arising out of dRTA (acidosis, hypokalemia) induce proximal tubular dysfunction or metabolic alterations associated with pRTA (hypophosphatemia) impair distal tubular acidification mechanisms, thus contributing to a mixed phenotype of type 3 RTA [9,10].

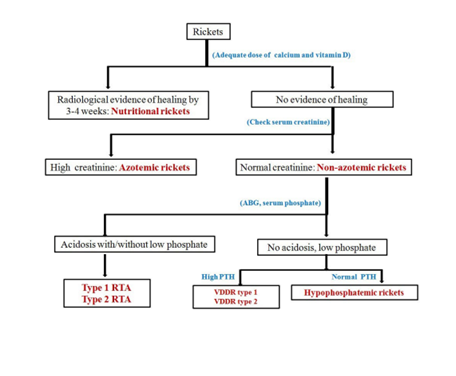

In children and adolescents, RTA may present with failure to thrive, growth retardation, hypokalemia, polyuria & polydipsia (due to defective urinary concentrating ability), nephrocalcinosis/nephrolithiasis (dRTA), and refractory rickets. The definition of refractory rickets is not universally accepted, however, absence of radiological healing lines after 3–4 weeks of adequate calcium and vitamin D suggests non-nutritional rickets. An approach to such cases has been summarized in Figure 3. Rickets and osteomalacia are common in dRTA and relatively uncommon in pRTA, unless associated significant acidosis and/or hypophosphatemia, as encountered in Fanconi syndrome. Features of rickets/osteomalacia are usually absent in incomplete dRTA and type 4 RTA unless the latter is associated with uremia

Figure 3: Approach to refractory rickets.

Rickets in RTA

Rickets in RTA is multifactorial. Systemic acidosis is associated with defective mineralization of the cartilages and bones due to increased solubility of the mineral phase. During acidosis, calcium and phosphate are mobilized from bones for the purpose of buffering by enhanced osteoclastic resorption. Enhanced activity of the osteoclasts is associated with influx of calcium and phosphate into the circulation. These molecules are subsequently excreted through kidneys due to following reasons: increased filtered load and reduced proximal tubular reabsorption (secondary to systemic acidosis). Hypercalciuria results in secondary hyperparathyroidism that further aggravates hypophosphatemia due to renal phosphate loss. In addition, pRTA itself may be associated with phosphaturia and low renal 1α-hydroxylase activity, which leads to impaired conversion of 25-hydroxy vitamin D to calcitriol (1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D), the active form of vitamin D.

Approach

A thorough clinical survey including that of the peripheral extremities, cranium, spine and eyes is of utmost importance. The authors recommend measurement of serum calcium, phosphate, albumin, ALP, PTH (by second generation assay), 25-hydroxy vitamin D, creatinine and arterial blood gas analysis at baseline in all children with rickets. Corrected serum calcium, then should be calculated using the formula: corrected calcium = measured calcium + 0.8 X (4-serum albumin). Absolute value of creatinine may be misleading in children; hence eGFR should be calculated using the Schwartz formula to rule out chronic kidney disease.

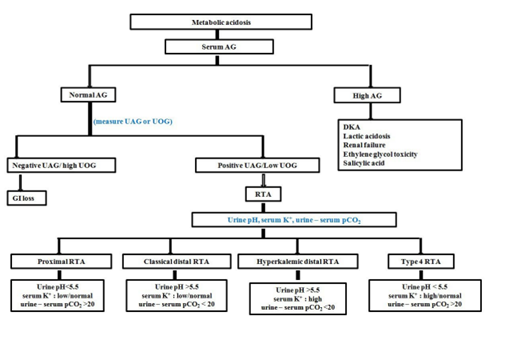

In patients with metabolic acidosis, the next step is measurement of serum AG [AG=Na+–(Cl-+HCO3-)]. Calculated AG should then be corrected for albumin using the formula: corrected AG = calculated AG + 2.4 X (4-serum albumin). Wide reference ranges of 3.0-12 mmol/L to 8.5-15 mmol/L for the AG have been reported owing to difference in laboratory methods [11]. The authors use a reference range of 12 ± 4 mmol/L; however, laboratory specific reference ranges for AG should be used.

Gastrointestinal (GI) loss of HCO3- due to diarrhea, external pancreatic/small bowel drainage, ureterosigmoidostomy, jejunal loop and drugs like calcium chloride, magnesium sulphate, and cholestyramine also result in hyperchloremic normal AG metabolic acidosis, hence, simulate RTA. Urinary AG (UAG) measurement is the next step; GI loss of HCO3- is associated with negative UAG, while positive UAG suggests RTA [12]. UAG is calculated by the formula: UAG=Urine [(Na++K+)–Cl-]. The sum of positive and negative ion charges must be equal; so ‘true’ AG does not exist in vivo (serum or urine). In urine, the sum of cations (Na++K++NH4+ + unmeasured cations) is equal to the sum of (Cl– + unmeasured anions).

The difference between urinary unmeasured anions (sulfates, phosphates, organic anions) and unmeasured cations (calcium, magnesium) is relatively constant at an approximate value of 80, therefore urinary Na++K++NH4+=Cl-+80, or NH4+=80-UAG, or UAG=80-NH4+ [13]. The equation, that is utilized to have an estimate of urinary NH4+ excretion, and numerically not much different from the above formula is urinary NH4+=82-0.8 X UAG [14]. Positive UAG suggests more unmeasured anions (SO42-, PO43-) and minimal or no NH4+ likely due to RTA, while a negative UAG suggests adequate urinary NH4+ due to normal urinary acidification system, hence GI loss of HCO3-. In summary, positive UAG (≈+20 to +90) in a background of normal AG metabolic acidosis is encountered in dRTA and pRTA when serum HCO3- is below threshold (14–18 mmol/L). On the other hand, negative UAG (≈-20 to -50) suggests GI loss of HCO3- or pRTA with HCO3- above threshold (14–18 mmol/L).

However, there are certain limitations to the use of UAG [15-18].

- UAG is of limited use if value of UAG is between -20 and +20

- UAG is unreliable when urine pH exceeds 6.5. Urine pH of more than 6.5 suggests significant urinary HCO3-, an anion that is not taken into consideration while calculating UAG.

- When anions other than Cl−, such as β-hydroxybutyrate or acetoacetate in ketoacidosis, hippurate in toluene intoxication, acetylsalicylic acid, D-lactic acid and large quantities of penicillin are excreted in the company of NH4+, the value for NH4+ derived using the UAG will significantly underestimate the actual urinary NH4+ excretion. However, all these conditions are associated with high AG metabolic acidosis, and should not be confounding UAG in RTA. Increased unmeasured urinary cations like lithium may also interfere with UAG interpretation at times.

- Acidification of urine requires adequate distal delivery of sodium. So, when distal Na+ delivery is impaired, as suggested by urinary Na+ <20-25 mmol/L, usefulness of UAG is questionable.

In these above situations urine osmolar gap (UOG) is an effective alternative. UOG=measured Uosm- calculated Uosm. Calculated Uosm=2X (serum [Na++K+] in mmol/L) + [blood urea nitrogen (in mg/dl)]/2.8 + [glucose (in mg/dl)]/18.

Modified UOG or UOG/2 is likely a true estimate of urinary NH4+, as it reflects the contribution of the anions accompanying NH4+ to the osmolality [19]. Urinary NH4+ of ≥75 mmol/L suggests intact NH4+ secretion, while urinary NH4+ of ≤25 mmol/L points towards inappropriately low NH4+ secretion. Some authors have suggested that UOG less than 40 mmol/L in patients with normal AG metabolic acidosis indicates impaired urinary NH4+ excretion, while urinary NH4+ is considered appropriately increased if the gap is above 100 [11,13]. To summarize, UOG of less than 40-50 mmol/L in a background of normal AG metabolic acidosis suggests dRTA and UOG of more than 100-150 mmol/L points against dRTA.

Once the diagnosis of RTA is established, the next step is to identify its type. Freshly voided early morning urine sample is tested for urine pH, a marker of urinary free H+ concentration, preferably with a pH meter. Urine should ideally be collected under mineral oil to prevent dissipation of CO2 and falsely elevated urine pH. Patient should not have urinary tract infection as urea spitting organisms are associated with falsely high urine pH. Minimum achievable urine pH with normal renal function and acidification is 4.5-5.3. Urine pH >5.5 in the presence of metabolic acidosis can be due to dRTA or pRTA with serum HCO3- above threshold or pRTA being treated with alkali. A filtered HCO3- that exceeds PCT re-absorptive capacity shall give falsely high urine pH. Urine pH <5.5 during metabolic acidosis suggests pRTA with serum HCO3- below threshold. Metabolic acidosis and hypokalemia associated with diarrhea may increase renal NH3 synthesis. In the presence of normal distal tubular H+ secretion, more renal NH4+ is produced, hence urine pH becomes alkaline (>5.5) in diarrhea. So, urine pH should always be performed once GI loss of HCO3- is ruled out with negative UAG or high UOG. Urinary Na+ less than 20-25 mmol/L is associated with low distal tubular H+ secretion, hence, falsely high urine pH. A suggested approach to normal AG metabolic acidosis has been summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Approach to metabolic acidosis.

Other tests, that are used to assess distal acidification defects in patients of incomplete dRTA are ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) challenge test, calcium chloride challenge test, frusemide plus fludrocortisone test and measurement of pCO2 difference between urine and blood after NaHCO3 infusion [20,21]. However, these tests are not required in a child with rickets secondary to RTA, as metabolic acidosis is florid in such cases.

pRTA is recognized by requirements for large quantities of base to raise serum HCO3- with the appearance of bicarbonaturia at a normal serum HCO3− concentration. pRTA in steady state is associated with metabolic acidosis (HCO3-: 14-18 mmol/L), acidic urine pH (<5.5) and low fractional HCO3− excretion (Fe-HCO3). Fe-HCO3 of more than 15–20% and urine pH higher than 7.5, when serum HCO3− is raised to normal values following infusion of NaHCO3, confirms pRTA [22].

Type 3 RTA was formerly thought to be more widespread, when first identified. Infants with dRTA were routinely found to possess coexisting significant urinary HCO3− wasting. It is now acknowledged that most young children with dRTA experience an initial transient phase of bicarbonaturia as part of the syndrome's natural history. The precise mechanism(s) of proximal tubular dysfunction in dRTA is yet to be crystallized and two potential explanations have been put forward. Intracellular acidosis secondary to systemic acidosis induces endosomal dysfunction in the proximal tubular cells in dRTA and results in proximal renal tubular cell dysfunction. Chronic hypokalemia also induces a number of pathological changes in renal proximal tubular cells (infiltration with inflammatory mononuclear cells, vacuolization, atrophy, destruction, brush border damage or even interstitial fibrosis) that culminates into proximal tubular dysfunction.

Unlike other forms of rickets, hypophosphatemia is uncommon in rickets associated with RTA. In a patient of hypophosphatemia, renal loss of phosphate should be differentiated from non-renal cause of phosphate wasting by calculating tubular reabsorption of phosphate (TRP) and tubular maximum for phosphate corrected for GFR (TmP/GFR). Phosphate reabsorption occurs mainly in the PCT, which reclaim roughly 80-85% of the filtered load. Additional 8-10% phosphate is reabsorbed in the distal tubule (but not in loop of Henle), leaving about 10-12% for excretion in the urine. The normal TRP, therefore, is about 90% [23]. TRP is calculated using the formula 1-[(Up/Sp) X (Scr/Ucr)] (U: urine; S: serum; p: phosphate; cr: creatinine).

TmP/GFR is maximum renal tubular phosphate reabsorption in mass per unit volume of glomerular filtrate. It is independent of the rate of phosphate flow into the extracellular space from gut, bone and glomerular filtration rate [24]. It was initially developed to differentiate hypercalcemia due to hyperparathyroidism from other causes of hypercalcemia that is now done by measuring PTH levels [25]. If TRP is less than or equal to 0.86 then TmP/GFR can be derived from standardized nomogram or multiplying TRP by serum phosphate. If TRP is greater than 0·86, Kenny and Glen’s equation is used [‘x’ = (0.3 X TRP) / {1-(0.8 X TRP)}] and TmP/GFR= ‘x’ X serum phosphate] [26,27]. TmP/GFR is compared with age and sex specific reference range, and normal value roughly corresponds with age and specific reference range for plasma phosphate. Low TmP/GFR in the presence of hypophosphatemia suggests renal phosphate loss [28]. Hypophosphatemia in RTA is secondary to renal loss, and likely due to pRTA. The affected child often has coexistent glycosuria, aminoaciduria, low-molecular weight proteinuria, hypercalciuria, uricosuria in varying combinations as a part of Fanconi syndrome. However, as discussed earlier, primary dRTA is also associated with reversible form of generalized defects in proximal tubular absorptive capacity resulting in phosphaturia, low molecular proteinuria, but, not glycosuria. Moreover, primary hypophosphatemic rickets or calciopenic rickets, by virtue of severe hypophosphatemia, may result in impaired HCO3- reabsorption from PCT (pRTA) or acquired, reversible distal acidification defect (dRTA). In addition to hypophosphatemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism associated with rickets associated with abnormal vitamin D homeostasis, also contribute to pRTA as PTH inhibits proximal tubular bicarbonate reabsorption by interfering with the activities of apical Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE3) and the basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase. Clinicians need to be vigilant to identify the underlying primary etiology in children with rickets, normal AG metabolic acidosis and hypophosphatemia.

Once the type of RTA is identified in a child with rickets, next step is to rule out important secondary causes and mutational analysis for genes responsible for primary forms of RTA (Table 1). At times, certain clinical clues may help to target specific genes for analysis. Accompanying features of CA-II mutation has already been discussed. In addition, eye changes and basal ganglion calcification in pRTA suggests NBC-1 defect, sensori-neural deafness in dRTA points towards H+ ATPase abnormality, hemolysis with dRTA suggests defective AE1 (Table 1). pRTA combined with epilepsy and osteopetrosis suggests involvement of the renal chloride channel (CLCN) gene 7 (CLCN7). Dent’s disease, an X-linked condition due to defective renal CLCN5, is associated with vitamin A-responsive night blindness, hypophosphatemic rickets and generalized PCT dysfunction, and closely mimics pRTA [29]. Recently, a second variant of Dent’s disease (Dent 2) due to mutation of oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe gene 1(OCRL1) has been identified [30].

Treatment

Alkali replacement is the mainstay of therapy in all forms of RTA with rickets. 1-1.5 mEq/Kg of non-volatile acids are generated normally per day that is excreted in the form of titrable acids/NH4+). Daily alkali requirement in RTA should take into account the H+ retained each day and urinary bicarbonate loss, which however is negligible in dRTA. The usual daily dose of alkali in dRTA is 1-2 mmol/Kg in adults and 4-8 mmol/Kg in children. Rapidly growing skeleton generates additional acid load in children. In addition, higher fixed urine pH in children is associated with relatively larger urinary bicarbonate loss compared to adults. Sodium bicarbonate or sodium citrate is often used and titrated to achieve and maintain normal serum HCO3- (22-24mmol/L). Correction of acidosis reduces urinary K+ and prevents hypokalemia, and patients may not require potassium supplementation in the long run. However, in presence of hypokalemia potassium citrate is preferred.

In contrast, owing to marked urinary HCO3- loss in pRTA, daily alkali requirement is much higher, 10-30 mmol/Kg, along with large supplementation of K+. Increased distal tubular Na+ and HCO3- delivery stimulates K+ secretion, hence, potassium citrate with/without sodium bicarbonate is the preferred form of therapy. Near normal HCO3- in children needs to be achieved. If large dose of alkali is ineffective to achieve target HCO3- or such a high dose is not tolerated, thiazide diuretics may be added. Mild volume depletion associated with thiazide diuretics enhances Na+ & HCO3- absorption in PCT. Those with severe hypophosphatemia should be co-prescribed phosphate supplement and active vitamin D metabolites.

Conclusions

RTA is a complex disease and, at times, difficult to diagnose due to the variable presentation. RTA is known to be associated with rickets, and RTA needs to be ruled out in all cases of ‘refractory rickets’. Arterial blood gas analysis is recommended at baseline in children with rickets along with other first line investigations. Evaluation for RTA begins with measuring serum AG in individuals having metabolic acidosis. Patients with normal AG metabolic acidosis should undergo testing for UAG with/without UOG. Once the cause is established to be due to RTA, urine pH can guide for confirming the specific type of RTA. Early recognition and specific management are rewarding as it enables relief of symptoms and complete clinical and radiological remission (Figures 5 and 6). If diagnosed late, deformity might be permanent, once growth plates are fused, that ultimately require corrective osteotomy.

Figure 5: 4.5-year-old girl with dRTA was treated with alkali therapy. Note the complete clinical (B) and radiological (D) recovery after 1.5 years of treatment. A and C represent features at presentation.

Figure 6: Residual deformity after 3 years of alkali therapy in a boy diagnosed with dRTA at 16 years of age. The growth plates are fused and the boy is posted for corrective osteotomy.

References

2. Sahay M. Homeostasis and disorders of calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. In: Vijaykumar M, Nammalwar BR, Eds. Principles and practice of pediatric nephrology. 2nd edition. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, 2013: 82

3. Yaxley J, Pirrone C. Review of the diagnostic evaluation of renal tubular acidosis. Ochsner Journal. 2016 Dec 21;16(4):525-30.

4. Soleimani M, Rastegar A. Pathophysiology of renal tubular acidosis: core curriculum 2016. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2016 Sep 1;68(3):488-98.

5. Batlle D, Flores G. Underlying defects in distal renal tubular acidosis: new understandings. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1996 Jun 1;27(6):896-915.

6. Igarashi T, Sekine T, Inatomi J, Seki G. Unraveling the molecular pathogenesis of isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2002 Aug 1;13(8):2171-7.

7. Brenner RJ, Spring DB, Sebastian A, McSherry EM, Genant HK, Palubinskas AJ, et al. Incidence of radiographically evident bone disease, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis in various types of renal tubular acidosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982 Jul 22;307(4):217-21.

8. Sly WS, Hewett-Emmett D, Whyte MP, Yu YS, Tashian RE. Carbonic anhydrase II deficiency identified as the primary defect in the autosomal recessive syndrome of osteopetrosis with renal tubular acidosis and cerebral calcification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1983 May 1;80(9):2752-6.

9. Rodriguez-Soriano J, Vallo A, Castillo G, Oliveros R. Natural history of primary distal renal tubular acidosis treated since infancy. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1982 Nov 1;101(5):669-76.

10. Agrawal SS, Mishra CK, Agrawal C, Chakraborty PP. Rickets with hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia and normal anion gap metabolic acidosis: not always an easy diagnosis. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2020 Jan 1;13(1).

11. Berend K, de Vries AP, Gans RO. Physiological approach to assessment of acid–base disturbances. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014 Oct 9;371(15):1434-45.

12. Kraut JA, Madias NE. Differential diagnosis of nongap metabolic acidosis: value of a systematic approach. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012 Apr 1;7(4):671-9.

13. Bagga A, Sinha A. Evaluation of renal tubular acidosis. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2007 Jul 1;74(7):679-86.

14. Goldstein MB, Bear R, Richardson RM, Marsden PA, Halperin ML. The urine anion gap: a clinically useful index of ammonium excretion. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1986 Oct 1;292(4):198-202.

15. Carlisle EJ, Donnelly SM, Vasuvattakul S, Kamel KS, Tobe S, Halperin ML. Glue-sniffing and distal renal tubular acidosis: sticking to the facts. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1991 Feb 1;1(8):1019-27.

16. Halperin ML, Kamel KS. Some observations on the clinical approach to metabolic acidosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010 Jun 1;21(6):894-7.

17. Halperin ML, Kamel K. Approach to the patient with metabolic acidosis: Newer concepts. Nephrology. 1996 Sep;2:s122-7.

18. Batlle DC, Riotte AV, Schlueter W. Urinary sodium in the evaluation of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987 Jan 15;316(3):140-4.

19. Dyck RF, Asthana S, Kalra J, West ML, Massey L. A modification of the urine osmolal gap: an improved method for estimating urine ammonium. American Journal of Nephrology. 1990;10(5):359-62.

20. Walsh SB, Shirley DG, Wrong OM, Unwin RJ. Urinary acidification assessed by simultaneous furosemide and fludrocortisone treatment: an alternative to ammonium chloride. Kidney international. 2007 Jun 2;71(12):1310-6.

21. Kim S, Lee JW, Park J, Na KY, Joo KW, Ahn C, et al. The urine-blood PCO2 gradient as a diagnostic index of H+-ATPase defect distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney International. 2004 Aug 1;66(2):761-7.

22. Santos F, Ordóñez FA, Claramunt-Taberner D, Gil-Peña H. Clinical and laboratory approaches in the diagnosis of renal tubular acidosis. Pediatric Nephrology. 2015 Dec 1;30(12):2099-107.

23. Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. Hormones and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB eds. William's Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020; 1196-1255

24. Bijvoet OL, Morgan DB, Fourman P. The assessment of phosphate reabsorption. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1969 Oct 1;26(1):15-24.

25. Payne RB. Renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate (TmP/GFR): indications and interpretation. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 1998 Mar;35(2):201-6.

26. Walton RJ, Bijvoet OL. Nomogram for derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet. 1975;2(7929):309-310.

27. Chong WH, Molinolo AA, Chen CC, Collins MT. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocrine-related Cancer. 2011 Jun 1;18(3):R53-77.

28. Imel EA, Econs MJ. Approach to the hypophosphatemic patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):696-706.

29. Sethi SK, Ludwig M, Kabra M, Hari P, Bagga A. Vitamin A responsive night blindness in Dent’s disease. Pediatric Nephrology. 2009 Sep 1;24(9):1765-70.

30. Bökenkamp A, Ludwig M. The oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe: an update. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(12):2201-2212.