Abstract

Purpose: This study aimed to clarify the correlations between values of diaphragmatic movement as respiratory muscle activity measured by ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) under quiet breathing (QB) and forced abdominal breathing (FAB) to select the optimal evaluation method according to the purpose of physical therapy, such as breathing instruction.

Materials and Methods: Twenty healthy young-adult volunteers participated and performed both QB and FAB. During breathing, the distance of diaphragmatic movement and diaphragm thickness was measured by US, followed by measurements of lung lengths in the sagittal and coronal planes by MRI. Correlations between parameter values measured by US and MRI were analyzed using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient.

Results: Under QB, significant positive correlations were found between the distance of diaphragmatic movement (Ddi/Ht) measured by US and the length of the mid-axillary line in the sagittal plane (SM/Ht) measured by MRI (r=0.602, p=0.005) and between the Ddi/Ht and posterior length in the sagittal plane (SP/Ht) (r=0.592, p=0.006). A significant correlation was also found between the length of the SM and tidal volume (r=0.591, p=0.012) during FAB. However, no significant correlation was found between US and MRI during FAB.

Conclusions: US is suitable for assessing narrow-range diaphragmatic activity, such as QB. However, for forced breathing, which increases respiratory muscle activity, MRI with a wider observation range that correlates with the ventilation volume is also indicated as an excellent evaluation tool. In conclusion, these findings might provide reference values for physical therapy investigation because understanding the mechanism of respiratory muscle movements is necessary for physical therapy, evaluation, and treatment of breathing disorders.

Keywords

Diaphragm, Respiratory muscle, Ultrasonography, MRI, Physiotherapy

Abbreviations

CCA: Coronal Carina Abdominal Length; CCT: Coronal Carina Thoracic Length; CL: coronal lateral length; CM: Coronal Midclavicular Length; Ddi: Distance of diaphragmatic movement; Ddi/Ht: Distance of diaphragmatic movement/height; FAB: Forced Abdominal Breathing; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PImax: Maximal inspiratory mouth pressure; PEmax: Maximal expiratory mouth pressure; QB: Quiet Breathing; SA: Sagittal Anterior length; SM: Sagittal Mid-Length; SP: Sagittal Posterior length; Tdi: Thickness of the diaphragm; TV: Tidal Volume; US: ultrasonography; VC: Vital Capacity; ZOA: Zone of Apposition

Introduction

Breathing instruction in physiotherapy is considered an important skill for the assessment and intervention [1,2] in diaphragmatic dysfunction associated with respiratory disorders. For respiratory physiotherapy, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of respiratory movements in the thorax and abdomen and to evaluate the laterality and difference in movements depending on the site.

Abdominal breathing, a typical breathing instruction model, is a breathing method using the diaphragm, which has high inspiratory efficiency [1,2]. However, the science-based practice guideline by the Japanese Society of Respiratory Physical Therapy determined that the evidence level and recommendation grade of this breathing instruction are only 4a and C, respectively [2]. Thus, an adequate understanding of the mechanism of respiratory movements is necessary for breathing instruction[1,2,3]. Inadequate demonstration of scientific efficacy is necessary because the scientific evidence on respiratory muscle activity and respiratory chest wall motion [4,5,6], which are the bases for breathing instruction, are limited, leading to non-unified assessments and interventions during physical therapy. Respiratory movements included inspiratory and expiratory muscle activities. The agonists for inspiration and expiration are the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, respectively [3,6,7]. Previous studies have provided various assessment indices for the measurement of diaphragm muscle activities and chest wall motions using ultrasonography (US) [8,9] and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [10-12]. Both of them are well-known non-invasive methods to observe deep-layer muscles. However, the observation field in US is limited within the range of the probe, only provides local findings of the muscles, has difficulty in assessing total images of diaphragmatic and thoracic motions, and shows limited deep spatial resolution [8]. Meanwhile, as advantages, it allows simple measurements without limitations in measurement positions or specific contraindications. MRI requires large equipment and limits measurement positions, intracorporeal metals, and other indications for examination [10]. Thus, only a few previous studies have compared measurements by US with those by MRI, no quantitative indices have been established for assessing respiratory muscles and respiratory movements, and their relationships were rarely investigated. Therefore, clarifying the relationships between indices measured by US and MRI is necessary to demonstrate the mechanism of respiratory movements for the assessment of respiratory muscle activities in physical therapy.

Thus, this study aimed to clarify the correlations between values measured by US and MRI during respiratory muscle activities to determine the optimal evaluation method according to the purpose of physical therapy, such as breathing instruction.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Kyorin University (approval no. 29-67).

We recruited 20 young healthy male or female volunteers who obtained explanations and descriptions about the purpose and details of the study (Table 1). Individuals who had respiratory, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, or neuromuscular diseases and who had a past medical history of thoracoabdominal surgery or smoking were excluded.

|

age (y/o) gender (male / female) height (cm) body weight (kg) |

22.0 ± 1.2 10 / 10 162.0 ± 7.5 54.0 ± 7.9 |

|

grip strength (kg) knee extension strength (kgf) |

33.3 ± 8.7 38.8 ± 11.2 |

|

%VC (L) TV (L) %FVC (L) FEV1% (%) PImax (cmH2O) PEmax (cmH2O) |

92.5 ± 12.1 0.5 ± 0.2 92.5 ± 13.1 91.8 ± 8.5 76.4 ± 13.8 83.7 ± 27.1 |

|

Mean ± standard deviation; %VC: %Vital Capacity; TV: Tidal Volume; %FVC: %Forced Vital Capacity; FEV1%: Forced Expiratory Volume in one second%; PImax: Maximal Inspiratory Mouth Pressure; PEmax; Maximal Expiratory Mouth Pressure |

|

Before the measurements, the participants were placed in the supine position with their knees slightly flexed and were instructed to practice resting quiet breathing (QB) and forced abdominal breathing (FAB). They were also instructed to practice QB and FAB during US and MRI, which were performed randomly.

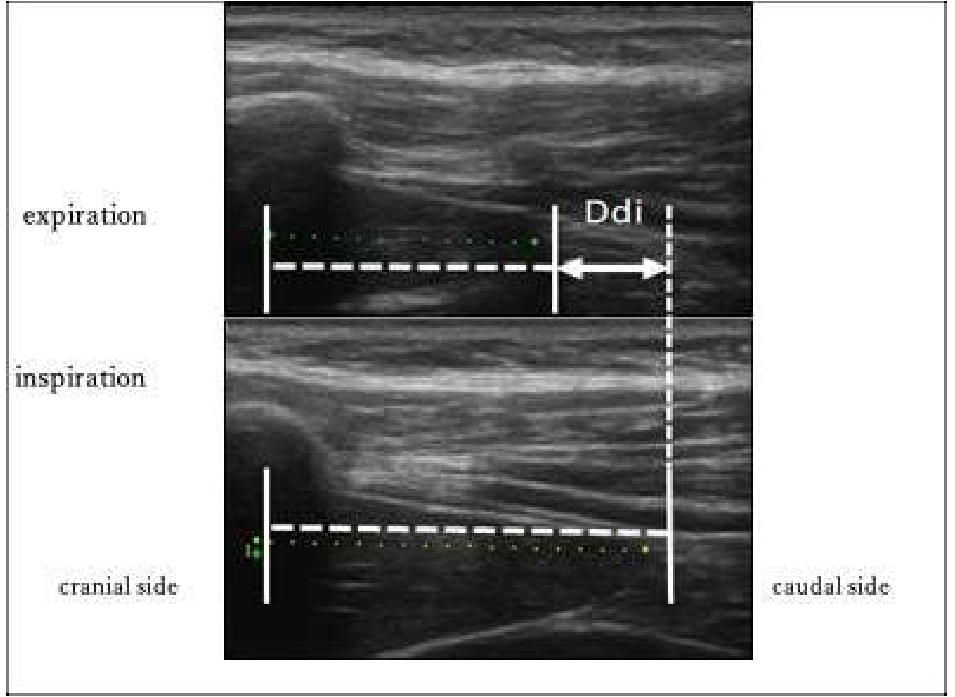

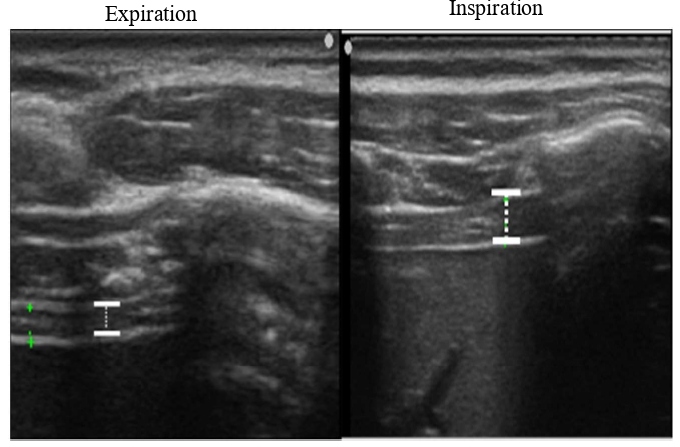

We imaged the distance of diaphragmatic movement (Ddi) and the thickness of the diaphragm (Tdi) using US (7.5 MHz linear probe, Ultrasound System ARIETTA Prologue, B-mode, Hitachi, Japan). The right side of the sites for measuring Ddi and Tdi was set as the region of interest because the left diaphragm is difficult to visualize given the presence of gastrointestinal organs [13-18]. The Ddi was imaged on the right mid-axillary line from the 9th–10th intercostal space to the upper border of the zone of apposition (ZOA) between the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line. Ddi was defined and measured as the change in the distance from any ribs in the visual field to the diaphragm [14,17,18]. Tdi was imaged at the ZOA on the mid-axillary line. According to the method by Wakai et al.[16], muscle thickness was imaged at the same site, and the difference in the muscle thickness between the end of inspiration and end of expiration was defined as the difference in the Tdi, which was used as an index of the amount of diaphragm activity (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Distance of diaphragmatic movement (Ddi) in US. Ddi: Distance of diaphragmatic movement; US: Ultrasonography.

Figure 2: Thickness of the diaphragm (Tdi) in US. TDi: Thickness of the Diaphragm; US: Ultrasonography.

In the image analyses [17,18], the following indices of respiratory muscle activity were calculated using the obtained images and an image-analyzing software (Image J®). The ratio of Ddi to height (Ddi/Ht) was also calculated using the following formula: Ddi/Ht (%) = Ddi (cm)/height (cm) × 100. The maximal muscle thickness was measured as Tdi during QB and FAB.

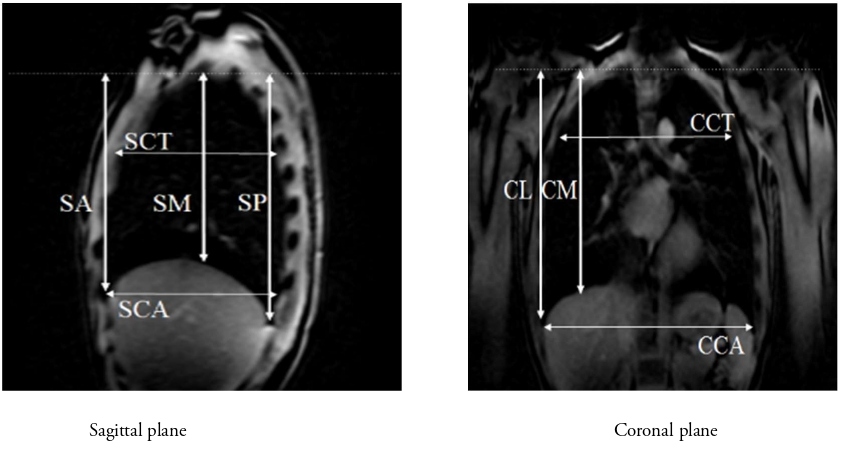

We used a 3.0T-MR Vintage Titan (Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Japan). The equipment was operated by physicians qualified as clinical radiologists and who were experienced in operating the MRI machine. Three-dimensional T1-weighted imaging and OsiriX (Newton Graphics) were used for analyzing MR data. The following lengths (Table 2) in the coronal plane (carina level) and sagittal plane (right midclavicular line level) were measured, and their ratio to height was calculated (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3: Lung measurements by MRI. MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SA: Sagittal Anterior length; SM: Sagittal Mid-length; SP: Sagittal Posterior length; CCT: Coronal Carina Thoracic length; CCA: Coronal Carina Abdominal length; CM: Coronal Midclavicular length; CL: Coronal Lateral length.

|

Coronal plane (carina level) |

|

Coronal lateral (CL): Length from the lung apex to the lateral border of the thorax Coronal mid (CM): Length from the lung apex to the midclavicular line Coronal carina thoracic (CCT): Transverse length at the carina level Coronal carina abdomen (CCA): Maximum transverse length of the lower thorax |

|

Sagittal plane (right midclavicular line level) |

|

Sagittal anterior (SA): Length from the lung apex to the anterior lower edge. Sagittal mid (SM): Length from the lung apex to the lower edge of the midaxillary line. Sagittal posterior (SP): Length from the lung apex to the posterior lower edge Sagittal carina thoracic (SCT): Length from the lung anterior edge to the posterior edge of the upper thorax Sagittal carina abdominal (SCA): Length from the lung anterior edge to the posterior edge of the lower thorax |

|

MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

We measured tidal volume (TV) using a spirometer under QB and FAB in the supine position during US.

Statistical analysis

Three examiners took measurements to calculate the indices of respiratory muscle activity. The median values were used after the intra-examiner reliability was verified. The paired t-test was used as a two-group test between values measured by US and MRI under each respiratory condition, and Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient was used to evaluate correlations between the measured indices and between the measured values and background factors. SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis, and a risk rate of less than 5% was defined as a significant level.

Results

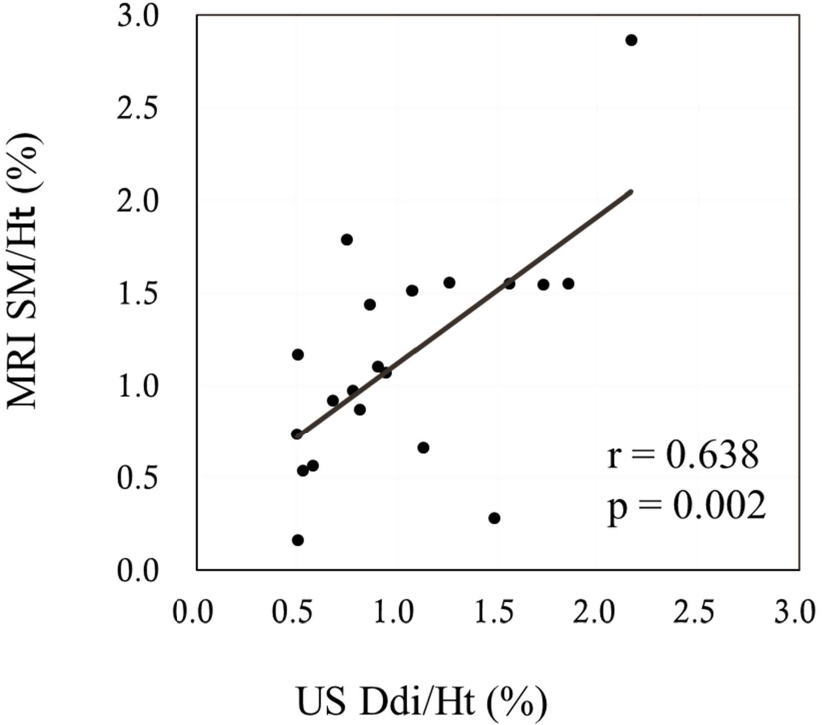

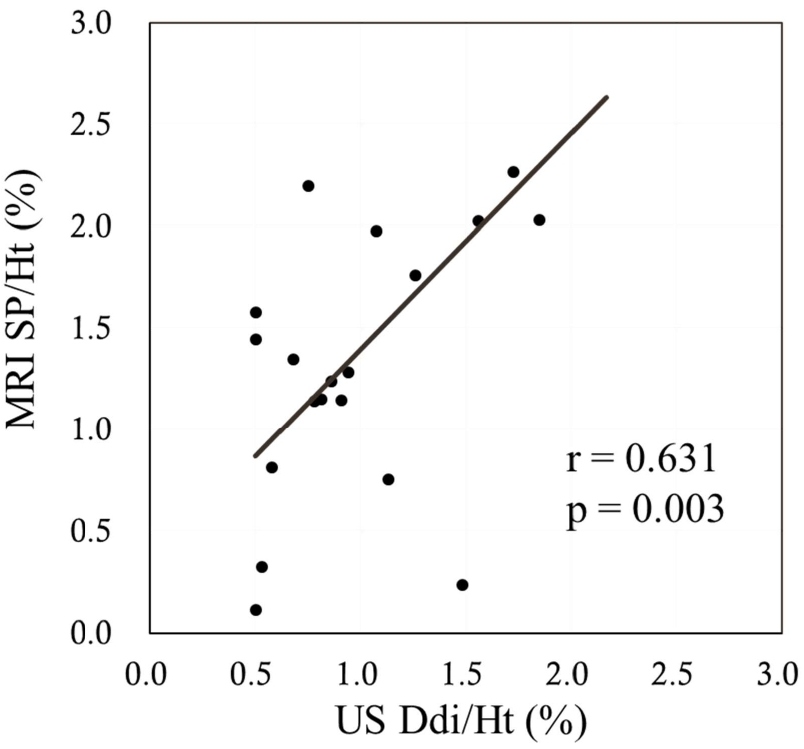

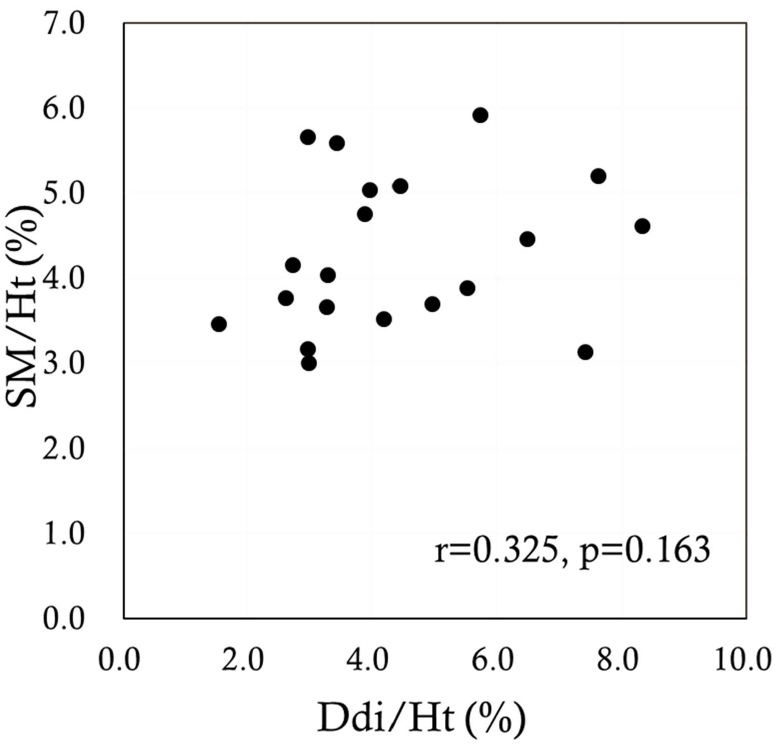

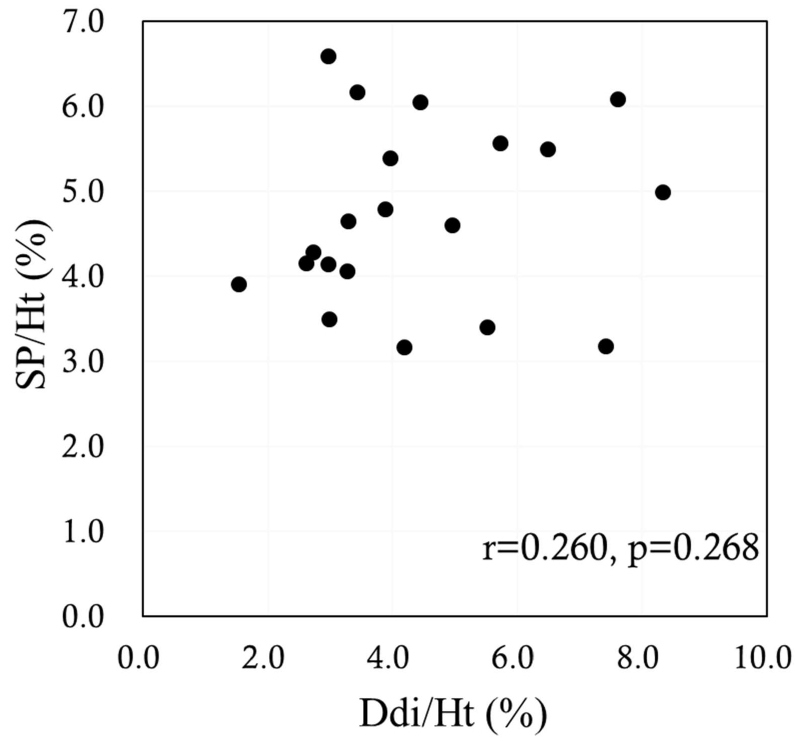

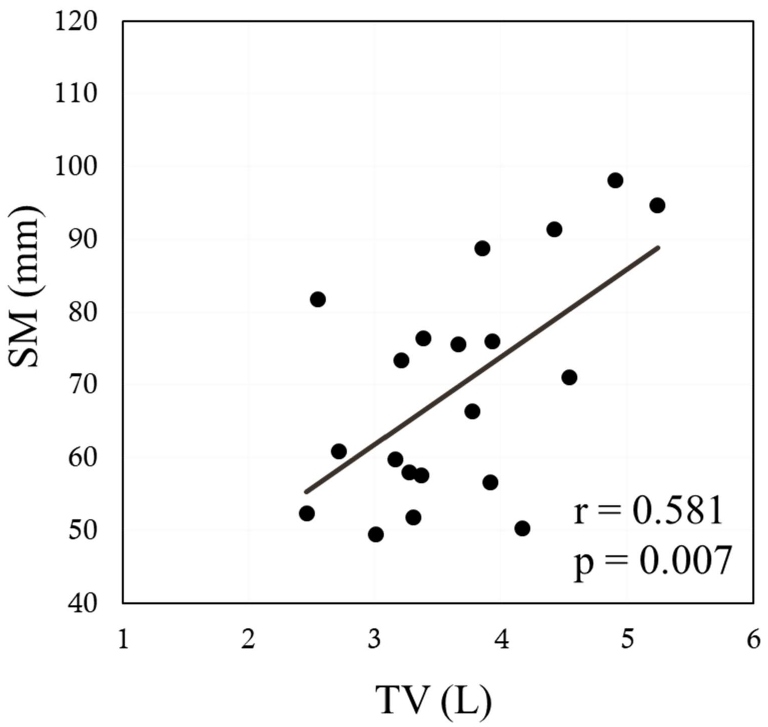

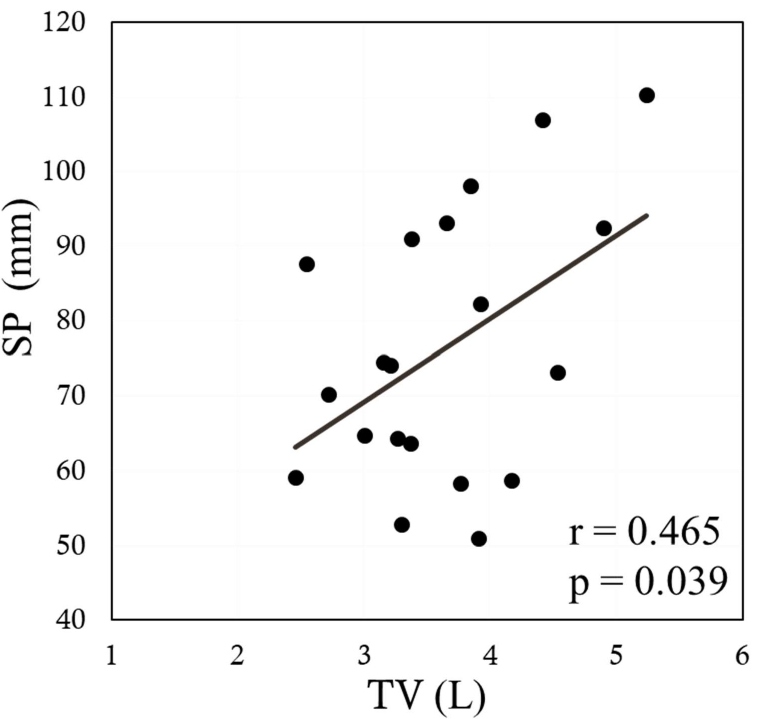

The sagittal anterior length, sagittal mid-length (SM), sagittal posterior length (SP), coronal lateral length, and coronal midclavicular length significantly increased more under FAB than under QB (p<0.001 in all). Ddi under FAB was significantly higher than that under QB (p<0.001). Significant positive correlations were noted between the indices measured by US and MRI, namely, between the Ddi/Ht and the SM/Ht and between the Ddi/Ht and the SP/Ht under QB (r=0.638, p=0.002; r=0.631, p=0.003, respectively) (Figures 4 and 5). By contrast, no significant correlations were noted between the Ddi/Ht and the SM/Ht and between the Ddi/Ht and the SP/Ht under FAB (r=0.325, p=0.163; r=0.260, p=0.268, respectively) (Figures 6 and 7). Meanwhile, significant correlations were noted between the SM and the ventilation volume and between the SP and the ventilation volume under FAB (r=0.581, p=0.007; r=0.465, p=0.039, respectively) (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 4: Relationship between the Ddi/Ht and the SM/Ht under QB. QB: Quiet Breathing; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SM/Ht: Sagittal Mid-length/Height; US: Ultrasonography; Ddi/Ht: Distance of diaphragmatic movement/Height.

Figure 5: Relationship between the Ddi/Ht and the SP/Ht under QB. QB: Quiet Breathing; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SP/Ht: Sagittal Posterior length/Height; US: Ultrasonography; Ddi/Ht: Distance of diaphragmatic movement/Height.

Figure 6: Relationship between the Ddi/Ht and the SM/Ht under FAB. FAB: Forced Abdominal Breathing; SM/Ht: Sagittal Mid-length/Height; Ddi/Ht: Distance of diaphragmatic movement/Height.

Figure 7: Relationship between the Ddi/Ht and the SP/Ht under FAB. FAB: Forced Abdominal Breathing; SP/Ht: Sagittal Posterior length/Height; Ddi/Ht: Distance of diaphragmatic movement/Height.

Figure 8: Relationship between the tidal volume and the SM/Ht under FAB. FAB: Forced Abdominal Breathing; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SM/Ht: Sagittal Mid-length/Height; TV: Tidal Volume.

Figure 9: Relationship between the tidal volume and the SP/Ht under FAB. MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SP/Ht: Sagittal Posterior length/Height; TV: Tidal Volume.

Discussion

A previous study evaluated the diaphragmatic activity and the relationship with the amount of ventilation using the MRI. In this study, we found a significant meaningful moderate equilateral coefficient of correlation between US and MRI under QB.

Recent studies have shown that diaphragmatic dysfunction or atrophy in patients with critical illness on mechanical ventilation is an under-recognized cause of respiratory failure and prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation [9,19-22]. Thus, diaphragmatic ultrasonography could be a useful and accurate tool to detect diaphragmatic function and/or dysfunction because diaphragmatic atrophy has received particular attention, as it affects weaning from ventilator and functional prognosis. However, studies have investigated patients with critical illness [23-28] who underwent mechanically positive pressure ventilation or limited TV ventilation. US is easy to use and is suitable for measuring Ddi in a narrow window, that is, in situations where the TV is relatively low. Tdi is not correlated with the distance of diaphragmatic movement, but its usefulness as an indicator of the degree of muscular atrophy is undeniable. Ddi and Tdi using US are conventional and non-invasive useful tools for measuring these local conditions or the range of diaphragmatic movements on the bedside. On the contrary, MRI requires a complex, expensive, and large device that cannot be easily used for examination, but it suits well for observing large diaphragmatic and thoracic movements, such as during FAB. Recent improvements in imaging hardware and software have led to the possibility of dynamic imaging of the diaphragm and the rib cage [10-12]. MRI can observe dynamic respiratory movement, and previous studies have also performed spirometry and phonation [29-35]. However, to measure respiratory muscle activities, a constant standard evaluation index has not been determined yet using MRI, given difficulties capturing images of air and identifying the outline of the lungs.

Moreover, previous studies have not directly compared US and MRI, and relationships between reference values were unknown even if both US and MRI are used to assess respiratory muscle activities and chest wall movement.

In the present study, the major findings were observed in the indices measured using US. The Ddi as a sagittal distance of diaphragmatic movement was only significantly correlated with the SM and SP measured by MRI, in which the measurement sites were close to each other in the longitudinal direction in the sagittal plane, observed only under QB. Moreover, no significant correlations were noted among other indices measured by US under QB and among indices measured by US and MRI under FAB. Even in previous studies using MRI, it is difficult to determine specific indicators. Fundamentally, MRI cannot depict air, so we identified the pleural signal at the interface with the lungs and determined the value of each index. In addition, considering the possibility of evaluating three-dimensional respiratory movements or diaphragmatic movements that can be visually shown in moving images, we selected and measured on multiple planes.

If a certain relationship can be secured between the US and MRI indicators, a more appropriate method suitable for the participant can be selected. Conversely, if the relationship is completely poor, the indicator should be used according to the purpose. Understanding the mechanism of respiratory muscle activities is necessary for physical therapy to evaluate and treat breathing disorders. Parameters measured by both US and MRI have advantages and disadvantages, and the relationships between indices measured by both methods have been rarely reported. In this study, as the observation by US was limited to within the range of the probe [29], differences would occur between the results of US and those of MRI.

Among physiotherapy interventions, breathing instructions are used in accordance with the characteristics of the participants for various purposes such as improving the efficiency of oxygen intake and carbon dioxide emission, suppressing oxygen consumption by correcting the ventilatory status, and reducing the work of respiration from a viewpoint of gas exchange[1-6]. Clarification of the relationships among parameters is expected to define indications for breathing instruction and contribute to the development of more effective methods for breathing instruction.

Under QB, significant correlations were noted between the Ddi measured by US and the SM and SP measured by MRI, whose measurement sites were close to each other in the sagittal plane. However, such a relationship was not found during FAB. Therefore, the assessment of diaphragmatic movement under QB suggested that both could have the same significance at certain sites in the sagittal plane. In the respiratory movement pattern of FAB, studies have reported that enhanced accessory inspiratory muscle activities acted on chest expansion in the longitudinal, coronal, and horizontal directions [2,35-37]. In addition, given the limited visibility range of the US probe, the respiratory movements could have displaced the landmarks themselves during US measurements, which could have been affected by the fact that the participants were healthy young adults with a flexible thorax[12,29,30] and that the movements of the upper thorax in the supine position were larger than those of the lower thorax [29,31] with the longitudinal expansion of the thorax in the sagittal plane limited by frictional resistance on the dorsal surface. Chest expansion is widely used as an index of respiratory movement [1,3,36,37], and previous studies have shown that chest expansion positively correlated with respiratory muscle activity and vital capacity [38]. Thus, it is necessary to understand the mechanism of respiratory movements with respiratory muscles to provide proper breathing instruction and to prove its effectiveness.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was conducted on a small number of healthy young people, and gender differences could not be distinguished. Second, the height correction value was used in the US, but it was not performed in MRI. Finally, we examined the representative indicators of US and MRI; however, since the standard evaluation indicators of MRI are unclear, there may be more useful indicators.

Conclusion

Certain correlations were noted between the indices of diaphragmatic and respiratory movements measured by US and MRI under QB. The results revealed that US can be easily used for individuals with relatively low ventilation, and MRI can be used to evaluate indicators depending on the physiotherapy, such as when evaluating larger and more dynamic respiratory movements.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Akane Sohma and Mari Morito for MRI data analysis. The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Funding/Disclosures

This work was supported by MEXT of Japan KAKENHI (15K01431 and 20K11243).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions statement

I, Masahiko Kimura, the corresponding author of the work certify that all authors have participated sufficiently in the conception and design of the work and were involved in the acquisition of data. All of them have also participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as drafting the work. All authors also revised the work and contributed to the final approval of the version for publication. Each author also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

2. The Japanese Society of Respiratory Physical Therapy, 2011, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Japanese Guidelines for the Physical Therapy.

3. Lee HY, Cheon SH, Yong MS. Effect of diaphragm breathing exercise applied on the basis of overload principle. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2017;29(6):1054-1056.

4. Kakizaki F, Ishizuka T. Measurement of respiratory motions using three-dimensional image measurement. Jpn J Clin Biomech. 2012;36:138-142.

5. Boussuges A, Gole Y, Blanc P. Diaphragmatic motion studied by m-mode ultrasonography: methods, reproducibility, and normal values. Chest. 2009 Feb 1;135(2):391-400.

6. Kaneko H. Changes in respiratory muscle activity during repeated measurements of maximal inspiratory pressure. Regakuryoho Kagaku. 2010; 25(4):487-92.

7. McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan PC, Critchley D. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clinical Biomechanics. 2004 May 1; 19(4):337-42.

8. Barbariol F, Deana C, Guadagnin GM, Cammarota G, Vetrugno L, Bassi F. Ultrasound diaphragmatic excursion during non-invasive ventilation in ICU: a prospective observational study. Acta Biomed. 2021 Jul 1;92(3):e2021269.

9. Zambon M, Greco M, Bocchino S, Cabrini L, Beccaria PF, Zangrillo A. Assessment of diaphragmatic dysfunction in the critically ill patient with ultrasound: a systematic review. Intensive Care Medicine. 2017 Jan; 43(1):29-38.

10. Traser L, Özen AC, Burk F, Burdumy M, Bock M, Richter B, et al. Respiratory dynamics in phonation and breathing-A real-time MRI study. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2017 Feb 1; 236:69-77.

11. Kondo T, Kobayashi I, Taguchi Y, Ohta Y, Yanagimachi N. A dynamic analysis of chest wall motions with MRI in healthy young subjects. Respirology. 2000 Mar; 5(1):19-25.

12. Cluzel P, Similowski T, Chartrand-Lefebvre C, Zelter M, Derenne JP, Grenier PA. Diaphragm and chest wall: assessment of the inspiratory pump with MR imaging-preliminary observations. Radiology. 2000 May; 215(2):574-83.

13. Naka T, Saito Y, et al. Measurement of costal and diaphragmatic motion using ultrasonic diagnostic equipment - for utilizing measurement of respiratory motion in the clinical setting. J Soc Biomech 2012; 36:142-150.

14. Kaneko H. Measurement of respiratory muscle activities using ultrasound imaging. J Soc Biomech 2016; 36:151-156.

15. Kawamoto H, Kambe M, Kuraoka T. Evaluation of the diaphragm in patients with COPD (emphysema dominant type) by abdominal ultrasonography. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi= the Journal of the Japanese Respiratory Society. 2008 Apr 1; 46(4):271-277.

16. Wakai Y. Diaphragmatic function measured by ultrasonography. J Tokyo Womens Med Coll. 1991;61:133-139.

17. Takimoto R, Ishii M, Kimura M, et al. Draw-in instruction focusing on inner trunk muscles increases the tidal volume. Kitasato Phys Ther. 2015;18:85-88.

18. Yamanobe A, Ishii M, Kimura M, et al. Influence of instruction on abdominal draw-in exercise on respiratory function. Kitasato Phys Ther. 2015;18:137-140.

19. Dres M, Jung B, Molinari N, Manna F, Dubé BP, Chanques G, et al. Respective contribution of intensive care unit-acquired limb muscle and severe diaphragm weakness on weaning outcome and mortality: a post hoc analysis of two cohorts. Critical Care. 2019 Dec;23(1):1-9.

20. Ueki J, De Bruin PF, Pride NB. In vivo assessment of diaphragm contraction by ultrasound in normal subjects. Thorax. 1995 Nov 1;50(11):1157-61.

21. Rocha FR, Brüggemann AK, Francisco DD, Medeiros CS, Rosal D, Paulin E. Diaphragmatic mobility: relationship with lung function, respiratory muscle strength, dyspnea, and physical activity in daily life in patients with COPD. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2017 Jan;43:32-7.

22. Boussuges A, Gole Y, Blanc P. Diaphragmatic motion studied by m-mode ultrasonography: methods, reproducibility, and normal values. Chest. 2009 Feb 1;135(2):391-400.

23. Mariani LF, Bedel J, Gros A, Lerolle N, Milojevic K, Laurent V, et al. Ultrasonography for screening and follow-up of diaphragmatic dysfunction in the ICU: a pilot study. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2016 Jun;31(5):338-343.

24. Valette X, Seguin A, Daubin C, Brunet J, Sauneuf B, Terzi N, et al. Diaphragmatic dysfunction at admission in intensive care unit: the value of diaphragmatic ultrasonography. Intensive Care Medicine. 2015 Mar;41(3):557-559.

25. Vassilakopoulos T, Petrof BJ. Ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004 Feb 1;169(3):336-41.

26. Doorduin J, Van Hees HW, Van Der Hoeven JG, Heunks LM. Monitoring of the respiratory muscles in the critically ill. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013 Jan 1;187(1):20-7.

27. Valette X, Seguin A, Daubin C, Brunet J, Sauneuf B, Terzi N, et al. Diaphragmatic dysfunction at admission in intensive care unit: the value of diaphragmatic ultrasonography. Intensive Care Medicine. 2015 Mar;41(3):557-559.

28. Mariani LF, Bedel J, Gros A, Lerolle N, Milojevic K, Laurent V, et al. Ultrasonography for screening and follow-up of diaphragmatic dysfunction in the ICU: a pilot study. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2016 Jun;31(5):338-43.

29. Tomita K, Sakai Y, Monma M, Ose H, Imura S. Dynamic MRI of normal diaphragmatic motions during spontaneous breathing and maximal deep breathing. Rigakuryoho Kagaku. 2004;19:237-43.

30. Terada T, Noguchi H, et al. Ventilatory mechanics: motions of lungs/thorax/respiratory muscles. Intensivist 2018;10:285-298.

31. Tomita K, Sakai Y, et al. Effect of inspiratory muscle training on the diaphragmatic excursion - a study of diaphragmatic motion analysis using dynamic MRI. Bulletin of Gumma Paz College. 2006;3:349-355.

32. Eichinger M, Puderbach M, Smith HJ, Tetzlaff R, Kopp-Schneider A, Bock M, et al. Magnetic resonance-compatible-spirometry: principle, technical evaluation and application. European Respiratory Journal. 2007 Nov 1;30(5):972-9.

33. Gierada DS, Curtin JJ, Erickson SJ, Prost RW, Strandt JA, Goodman LR. Diaphragmatic motion: fast gradient-recalled-echo MR imaging in healthy subjects. Radiology. 1995 Mar;194(3):879-84.

34. Hatabu H, Chen Q, Stock KW, Gefter WB, Itoh H. Fast magnetic resonance imaging of the lung. European journal of radiology. 1999 Feb 1;29(2):114-132.

35. Kolar P, Sulc J, Kyncl M, Sanda J, Neuwirth J, Bokarius AV, et al. Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2010 Oct;109(4):1064-1071.

36. Tabira K. Influence of chest expansion on pulmonary function and dyspnea in patients with chronic respiratory failure. Rigakuryouhougaku (Journal of the Japanese Physical Therapy Association). 1998;25:376-380.

37. Shobo A, Kakizaki K. Relationship between chest expansion and the change in chest volume. Rignku ryohougaku. 2014;29:881-884.

38. Suzuki K, Takahashi H. The study on usefulness of assessment of respiratory expansion using a tape measure for predicting pulmonary functions in old aged persons. J Jpn Soc Resp Care Rehab. 2007;17:148-152.