Abstract

In recent years, the use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) or “vape” in which nicotine is the major component has been dramatically increasing, particularly among teenagers and young adults. This is due to a general perception that e-cigarettes are harmless to use, in particular for the cessation of tobacco smoking. Thus, a better understanding of whether e-cigarettes pose a risk to human health is urgently needed. Nicotine exposure can accelerate malignant growth of cancer cells. The important link of nicotine to cancer risk comes from genomic-wide screens that reveal the association of gene polymorphisms of some of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunits with the increased risk of lung cancer. A series of studies demonstrate that chronic nicotine exposure upregulates Ras signaling, disrupts redox state and mitigates tumor suppressor functions (such as p53), leading to perturbed cell growth restriction and further weakening of the genomic stability of lung epithelial cells. Once second event (such as loss of p53) occurs, nicotine is able to promote the colony formation of lung epithelial cells in soft agar medium. Taken together, these investigations indicate that persistent nicotine exposure stimulates mitogenic signaling pathways and perturbs the cellular surveillance, which creates a micro-environment that is in favor for lung tumorigenesis. Importantly, these studies substantiate our concerns about health risks associated with e-cigarette smoking, especially in young adults.

Keywords

E-cigarettes, Nicotine, Mitogenic signaling, Genetic stability

E-Cigarette and Nicotine

E-cigarettes are electronic delivery devices that heat a solution containing mainly nicotine and some flavors to generate vapor, which resembles cigarette smoking without burning tobacco [1-3]. Nicotine solution of e-cigarettes also contains glycol or glycerin as a carrier of nicotine and flavors. With more advanced e-cigarette devices, voltages can be regulated so that higher concentrations of nicotine can be delivered under higher voltages [1-3]. This tobacco smoke replacement or “vaping” emerged on markets around 2007 and has since been popular among teenagers and young adults [4-6]. The users, also called vapers, inhale the generated aerosol (referred as “vapor”) containing high levels of nicotine that reaches or exceeds amounts in conventional tobacco cigarettes. Because e-cigarette smoking does not produce tar products, it has been viewed as harmless to human health and a good replacement of tobacco smoking, although there is no strong evidence given for such perception yet. Therefore, in recent years, the number of e-cigarette smokers, particularly among middle or high school and college students, has been rising in an exponential fashion [7-9]. Among young adults, many of them had no prior smoking experience.

Nicotine, as a main component in e-cigarettes, is not a conventional carcinogen, but an addictive substance that can rapidly diffused into tissues, especially in brain where it affects behavioral responses [10]. Although e-cigarettes appear helping people to quit tobacco smoking, there are other, more effective smoking cessation medicines [11]. The serious concerns about nicotine stem from our ignorance of how its addiction acquired at very young ages affects brain development or behavioral patterns; whether its exposure poses health risk in general; and how its inhalation influences on fetal growth when a mother is a frequent user. In addition, there has been almost no regulation of e-cigarette market or official warning to the end-users. The lack of knowledge poses an urgent need for a better understanding of the potential risk of e-cigarettes or nicotine for human health. Although reviews and studies focusing on the concerns about e-cigarettes have been published [12-14], in the following we concentrate on our experimental data demonstrating the potential roles of nicotine in the disruption of cell growth signaling and further perturbation of genetic integrity of lung cells for establishing a microenvironment favoring cancer initiation and progression.

Nicotine and Nicotinic Receptor

In the brain, nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and stimulates certain neuronal functions that affect the psychoactive and addictive actions of tobacco or e-cigarette smokers [10]. The neuronal nAChR is the ligand-gated ion channel and, consists of 10 α and 4 β subunits [15]. nAChR subunits can either form heterodimers with both α and β subunits or homodimers with one type of α subunit. In the central nerve system (CNS), nAChR is often composed of homologous subunits that are surrounding an ion channel to allow ion flow passing through.

nAChRs are also expressed in non-neuronal cells throughout the body. Unlike those in the CNS, the distribution of nAChR subunits in non-neuronal cells is less diverse. For example, human bronchial epithelial cells express only α3, α5, α7, β2 and β4 subunits [16-19] and keratinocytes express only α3 and α7 subunits [16-20]. The airway and lung are the primary contacting routes of smoking, where nicotine was shown to stimulate endothelial-cell proliferation via its ligation with nAChR [21,22]. High levels of nAChR have been detected in the lung and the receptor functions in a non-neuronal cholinergic autocrine-paracrine loop in lung epithelium and regulates lung development [23-25]. Mouse experiments revealed that the prenatal nicotine exposure decreased air flows in the airways of offspring, accompanied with increased airway branching and aberrant lung growth [26,27]. This effect of nicotine was correlated with the upregulation of the α7 of AChRs [27,28]. In vivo data also strongly suggest a nicotine effect on airway or lung development. By narrowing the airways diameters, prenatal nicotine exposure appears restricting air flow exchanges of the lung of the fetus [26-28]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that nicotine, via binding to nAChR, is able to stimulate endothelial cells and smooth-muscle cells to release basic fibroblast growth factor, prostacyclin and endothelin, respectively [29-33]. Furthermore, nicotine exposure has been shown to damage endothelial cells and therefore, impair angiogenesis [34,35]. In the course of inflammation, ischemia, tumor and atherosclerosis, nicotine is able to stimulate pathological angiogenesis, which promotes the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and tumorigenesis [33].

Mitogenic Growth Stimulated by Nicotine

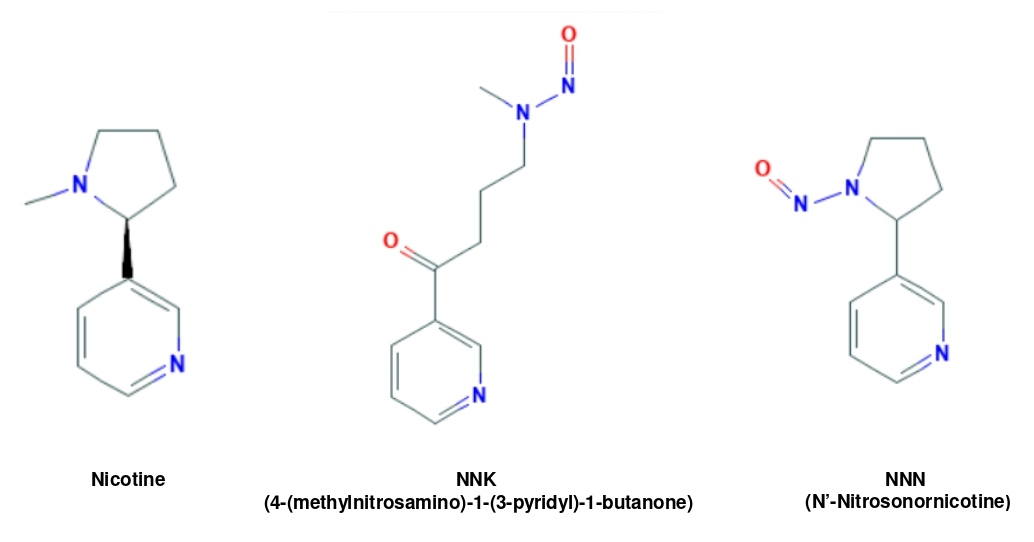

Because of its structural similarity with the well-known tobacco carcinogens 4-methylnitrosamino-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) (Figure 1), nicotine possesses some of their properties, such as promotion of cell growth or angiogenesis, which suggest a role in tumorigenesis [12]. It was shown that the expression level of the α7 of nAChR is augmented in most of small cell lung cancer cell lines treated with nicotine, leading to the acceleration of the growth of these cancer cells [21]. In Q-F 18 cells that are quail-origin fibroblasts ectopically over-expressing nAChR, fyk and fyn kinases that are the members of src kinase family were responsible for the activation of nAChR induced by nicotine [36]. In pancreatic cancer cells, nicotine, via activating src/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, accelerates pancreatic tumor angiogenesis and migration [37]. Moreover, in response to transient or chronic nicotine exposure, Ras is activated in lung epithelial cells or keratinocytes, which further mobilizes several mitogenic signaling pathways (including MAPK or Akt) [21,36,37]. Because active Ras is frequently detected in more than 30% of human cancer patients [38,39], the ability of nicotine to upregulate Ras and its downstream effectors strongly indicates its detrimental potential in tumorigenesis.

Figure 1: Similarity of the chemical structures among nicotine, NNN and NNK.

Persistent Upregulation of ROS and Induction of ER Stress by Chronic Nicotine Exposure

Free radicles (such as ROS) play important roles in the induction of oxidative or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in cells [40,41]. By damaging cellular macromolecules (DNA, RNA, lipids and proteins), oxidative or ER stress is linked causatively to the perturbation of genetic stability and further potentiation of tumorigenesis. Unlike tobacco smoke, nicotine exposure through e-cigarette smoke appears not to cause severe DNA damage [3,4]. However, some studies suggest that the vehicles in e-cigarette liquid acted together with nicotine and could disrupt cellular redox balance [2,14]. Oxidative stress, through activating nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-kB), has been shown to be elicited in nicotine-treated rat mesencephalic cells [42]. The expression of the adaptor protein p66shc (a key regulator of oxidative stress in the mitochondria) was increased, which caused renal oxidative stress in mice after chronically exposed to nicotine [40]. Further, nicotine was shown to be capable of inducing ROS in cancer cells [43].

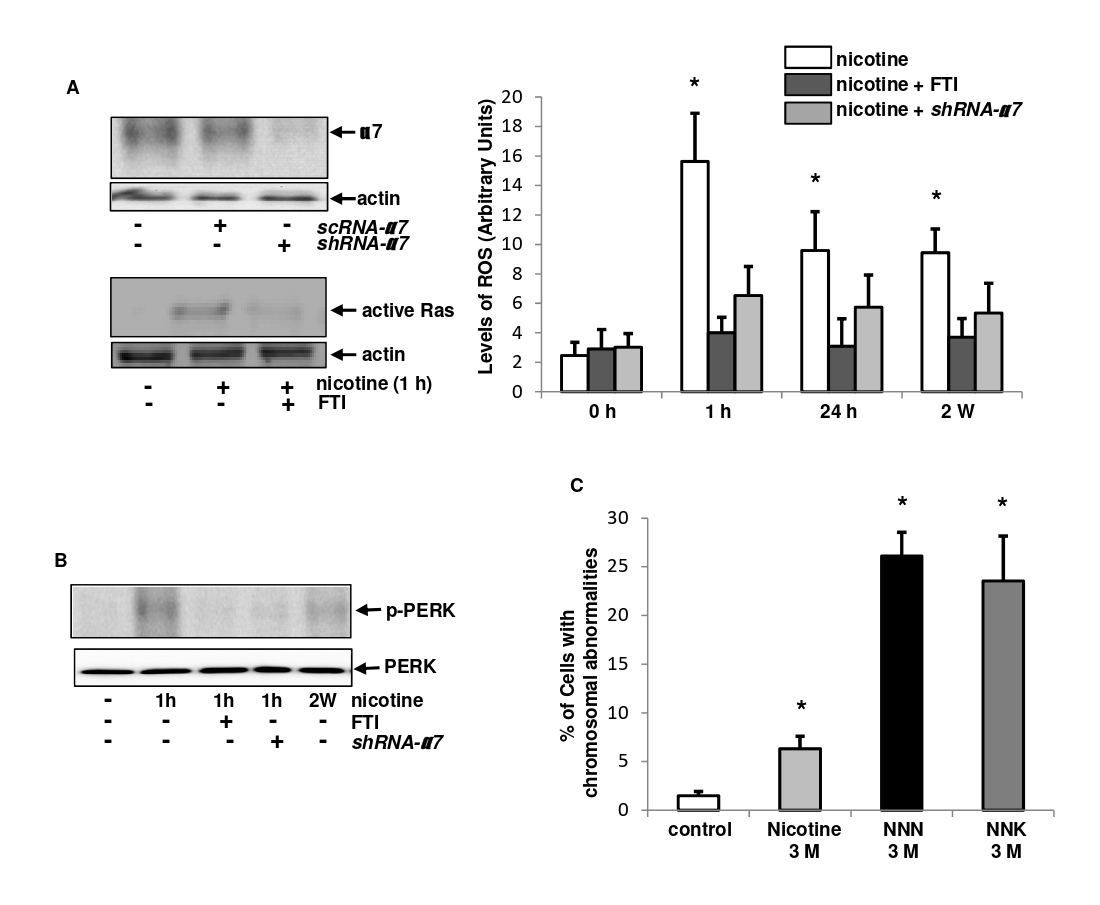

Oncogenic or mutant Ras and its downstream effectors (such as Akt) are important ROS and ER stress inducers [41-43]. To test the induction of ROS and its dependency on the receptor or Ras, the knockdown of nAChR α7 subunit by the shRNA or inhibition of active Ras by farnesyltransferase (FTI, a Ras inhibitor) in BEAS-2B cells was first tested (Figure 2A, left panels). The shRNA, but not scRNA, successfully blocked the α7 expression. The active Ras pull-down assay also showed that FTI blocked nicotine-mediated Ras activation. Afterward, ROS levels in BEAS-2B cells treated with nicotine for different time periods, with or without the knockdown of the α7 or the addition of FTI, were analyzed (Figure 2A, right panel). The level of ROS was increased in response to 1 h of nicotine treatment, which was declined, but remained at a moderately elevated level after the prolonged treatment (24h and 2 weeks). However, ROS upregulation induced by nicotine was suppressed by the knockdown of the α7 or addition of FTI. It indicates that the induction of ROS by nicotine in the lung cells is dependent upon nAChR (mainly α7) and Ras. The incomplete inhibition of the increased ROS by the α7 knockdown suggests the involvement of other nAChR subunits, which deserves further investigations.

Figure 2: Effect of nicotine on ROS, ER stress and genomic stability.

Persistent increases of ROS often lead to ER stress and further disruption of cellular or genomic structures [44]. Under normal growth conditions, the binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP, a chaperone) associates with and sequesters inactive forms of unfolded protein response (UPR) sensors, but dissociates from the active sensors during ER stress [44]. Upon nicotine exposure, BIP and protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) are activated [43]. To further test these in our experimental setting, the expression of the phosphorylated PERK was analyzed in BEAS-2B cells after transient nicotine treatment and its co-treatment with FTI or under the α7 knockdown condition (Figure 2B). PERK was phosphorylated after 1 h of nicotine treatment, which was blocked by FTI or shRNA-α7. In addition, a moderate level of the p- PERK could still be detected after 2 weeks of nicotine exposure. Taken together, these data suggest that the ligation of nicotine with its receptor, by activating Ras and ROS signaling, appears triggering oxidative stress in normal lung epithelial cells.

Compromising Genetic Integrity by the Prolonged Nicotine Exposure

Genome-wide screening studies linked the polymorphisms of some of nAChR subunits to increasing risk of lung cancer, in which 3 nAChR subunits genes are located at the chromosome 15q25.1 and associated with the risks of lung cancer [45,46]. Within this cluster, the single nuclear polymorphism (SNP) of the α5 mutation appeared affecting cellular activities [46-48]. Although the biological role of the SNP is not fully understood, the correlation of the polymorphism with the susceptibility of nicotine exposure to lung cancer or other diseases emphasizes the importance of this major e-cigarette component in tumorigenesis.

Besides genetic studies, the induction of oxidative stress and mitigation of the tumor suppressor functions (such as p53) triggered by chronic nicotine exposure also weigh in on the potential of nicotine to perturb genomic integrity. To further test this, BEAS-2B cells treated with nicotine, NNN or NNK for 3 months. Cytogenetic analysis was then performed as: after colcemid treatment, metaphase chromosomal spreads of the cells were prepared using hypotonic solution and assayed for chromosomal abnormality (such as chromosome multi-ploidy and aneuploidy) (Figure 2C). In comparison with the untreated controls. the percentage of the cells with aberrant chromosomes was slightly increased after the long-term nicotine treatment, but was much lower than that caused by the conventional carcinogen NNN or NNK. Slightly increased chromosomal abnormality indicates that nicotine is a weak genotoxic reagent, but through a long period exposure, appears being able to weaken genomic stability. Combined, the concomitant-conditions of perturbed oxidative redox state and occurring oxidative stress induced by nicotine-weakened genomic stability of cells, provide a microenvironment favoring tumorigenesis.

In summary, e-cigarettes do not contain carcinogens and toxins as in the conventional cigarettes, and appear beneficial for the cessation of tobacco smoking. However, their main component nicotine is a highly addictive substance and proven to have negative effects on brain development and function [1-4]. Moreover, nicotine, via nAChR, is able to alter normal cell signal transduction, the homeostatic machinery and genotoxic responses. Although our understanding of nicotine action in non-neuronal cells or tissues is still limited, existing data already provide ample indications of serious risks that are associated with the use of e-cigarettes, particularly for the brain development and physical health of teenagers and young adults, since they begin consuming e-cigarette smoke at early ages and may be exposed for a long time.

References

2. Talih S, Balhas Z, Eissenberg T, Salman R, Karaoghlanian N, Hellani EI, et al. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015; 17(2): 150-7.

3. Grana R, Benowitz NB, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: A scientific review. Circulation. 2014 Sep; 129 (19): 1972-86.

4. Grana RA, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Electronic nicotine delivery systems in the hands of Hollywood. Tob Control. 2011 Nov; 20 (6): 425-6.

5. Ganesan SM, Dabdoub SM, Nagaraja HN, Scott ML, Pamulapati S. Adverse effects of electronic cigarettes on the disease-naive oral microbiome. Science Advances. 2020; 6 (22): 1-10.

6. Rooke C, Amos A. News media representations of electronic cigarettes: an analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK and Scotland. Tob Control. 2014 May; 23 (6): 507-12.

7. Porter L, Duke J, Hennon M, Dekevich D, Crankshaw E, Homsi G, et al. Electronic cigarette and traditional cigarette use among middle and high school students in Florida, 2011-2014. Plos One. 2015 May; 10 (5):e0124385.

8. Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e- cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015 Jan; 135 (1): e43-e51.

9. Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Adolescent vaping and nicotine use in 2017–2018 — U.S. national estimates. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan; 380 (2): 192- 3.

10. Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009; 49: 57-71.

11. Corelli RL, Hudmon KS. Medications for smoking cessation. Western J of Med. 2002 Mar; 176 (2):131-5.

12. Grando SA. Connections of nicotine to cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2014 Jun;14 (6): 419-29.

13. Schaal C, Chellappan SP. Nicotine-mediated cell proliferation and tumor progression in smoking-related cancers. Mole Cancer Res. 2014 Jan; 12 (1): 14-23.

14. Spindel ER, McEvoy CT. The Role of nicotine in the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on lung development and childhood respiratory disease: implications for dangers of e-cigarettes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Mar; 193 (5): 486-94.

15. Gotti C, Clementi F. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2004 Dec; 74 (6):363-96.

16. Song P, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Keller JA, Spindel ER. Acetylcholine is synthesized by and acts as an autocrine growth factor for small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003 Jan; 63 (1): 214-21.

17. Egleton RD, Brown KC, Dasgupta P. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in cancer: multiple roles in proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008 Mar; 29 (3):151-8.

18. Paleari L, Negri E, Catassi A, Cilli M, Servent D. Inhibition of nonneuronal alpha7- nicotinic receptor for lung cancer treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Jun; 179 (12):1141-50.

19. Arredondo J, Nguyen VT, Chernyavsky AI, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA. A receptor-mediated mechanism of nicotine toxicity in oral keratinocytes. Lab Inves. 2001; 81: 1653-68.

20. Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD. Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004 May; 145 (5): 2498-506.

21. Dasgupta P, Rizwani W, Pilai S, Kinkade R, Kovacs M, Rastogi S, et al. Nicotine induces cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009 Jan; 124 (1): 36-45.

22. Gibbs K, Collaco JM, McGrath-Morrow SA. Impact of tobacco smoke and nicotine exposure on lung development. Chest. 2016 Feb; 149 (2): 552-61.

23. Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD, Lindstrom J, et al. Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004 May; 145 (5): 2498-2506.

24. Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ. Acetylcholine beyond neurons: the non-neuronal cholinergic system in humans. Br J Pharmacol. 2008 Aug; 154 (8): 1558-71.

25. Zoli M, Pucci S, Vilella A, Gotti C. Neuronal and extraneuronal nicotinc acetylcholine receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018; 16 (4): 338-49.

26. Wuenschell CW, Zhao J, Tefft JD, Warburton D. Nicotine stimulates branching and expression of SP-A and SP-C mRNAs in embryonic mouse lung culture. Am J Physiol. 1998 Jan; 274 (1):L165-L70.

27. Wongtrakool C, Roser-Page S, Rivera HN, Roman J. Nicotine alters lung branching morphogenesis through the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007 Sep; 293 (3): L611-L18.

28. Wongtrakool C, Wang N, Hyde DM, Roman J, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters lung function and airway geometry through a7 nicotinic receptors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012 May; 46 (5): 695-702.

29. Boutherin-Falson O, Blaes N. Nicotine increases basal prostacyclin production and DNA synthesis of human endothelial cells in primary cultures. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1990; 32 (4): 253-8.

30. Carty CS, Soloway PD, Kayastha S, Bauer J, Marsan B, Ricotta JJ, et al. Nicotine and cotinine stimulate secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and affect expression of matrix metalloproteinases in cultured human smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg. 1996 Dec; 24 (6): 927-34.

31. Lee WO, Wright SM. Production of endothelin by cultured human endothelial cells following exposure to nicotine or caffeine. Metabolism. 1999 Jul; 48 (7): 845-8.

32. Cucina A, Sapienza P, Corvino V, Borrelli V, Mariani V, Randone B, et al. Nicotine- induced smooth muscle cell proliferation is mediated through bFGF and TGF-β1. Surgery. 2000 Mar; 127 (3): 316-22

33. Heeschen C, Jang JJ, Weis M, Pathak A, Kaji S, Hu RS, et al. Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nature Med. 2001 Jul; 7 (7): 833-9.

34. Krupski WC. The peripheral vascular consequences of smoking. Ann Vasc Surg. 1991 May; 5 (3): 291-304.

35. Powell JT. Vascular damage from smoking: disease mechanisms at the arterial wall. Vasc Med. 1998; 3 (1): 21-8.

36. Mohamed AS, Swope SL. Phosphorylation and cytoskeletal anchoring of the acetylcholine receptor by src class protein tyrosin kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999 Jul; 274 (29): 20529-39.

37. Trevino JG. Pillai S, Kunigai S, Singh S, Fulp WJ, Centeno BA, et al. Nicotine induces inhibitor of differentiation-1 in a src-dependent pathway promoting metastasis and chemoresistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2012 Dec; 14 (12): 1102-14.

38. Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020 Jul; 80 (14): 2969-74.

39. Arany I, Clark J, Reed DK, Juncos LA. Chronic nicotine exposure augments renal oxidative stress and injury through transcriptional activation of p66shc. Nephrol Dial Trnasplant. 2013 Jun; 28 (6): 1417-25.

40. Andrikopoulos GI, Zagoriti Z, Topouzis S, Poulas K. Oxidative stress induced by electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS): focus on respiratory system. Cur Opin in Toxicol. 2019; 13: 81-9.

41. Barr J, Sharma CS, Sarkar S. Wise K, Dong L, Periyakaruppan A, et al. Nicotine induces oxidative stress and activates nuclear transcription factor kappa B in rat mesencephalic cells. Mole Cell Biochem. 2007 Mar; 297 (1-2): 93-9.

42. Zhang Q, Ganapathy S, Avraham H, Nishioka T, Chen C. Nicotine exposure potentiates lung tumorigenesis by perturbing cellular surveillance. Bri J Cancer. 2020 Mar; 122 (6): 904- 11.

43. Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2004 Jan; 14 (1): 20-8.

44. Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Zaridze D, et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature, 2008 Apr; 452 (7187):633-7.

45. Wang JC, Cruchaga C, Saccone NL, Bertelsen S, Liu P, Budde JP, et al. Risk for nicotine dependence and lung cancer is conferred by mRNA expression levels and amino acid change in CHRNA5. Hum Mol Genet, 2009 May; 18 (16): 3125-35.

46. Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, et al. A varian associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature, 2008 Apr; 452 (7187): 638-42.

47. Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IPm Gu J, Eisen T, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 2008 May; 40 (5): 616-22.