Abstract

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019 marked the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a disease known to be primarily associated with respiratory symptoms. However, as the pandemic unfolded, it became evident that SARS-CoV-2's impact extended beyond the respiratory system, infiltrating other bodily tissues, including the vascular system. Moreover, individuals with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes and hypertension were found to be more susceptible to severe and often fatal outcomes following COVID-19 infection. Clinical observations during the pandemic underscored the significance of the vasculature in COVID-19 pathology, revealing issues like hypercoagulation (excessive blood clotting), cardiomyopathy (abnormal heart muscle function), heart arrhythmias, and endothelial dysfunction (damage to the inner lining of blood vessels). In the aftermath of COVID-19, which is often referred to as post COVID, there is evidence of systemic vascular issues. However, the specific mechanisms behind these problems remain unclear, and the methods of treatment are not well-defined. This commentary offers a comprehensive examination of the available literature, presenting an analysis of the involvement of vascular issues in post-COVID situations, along with a deeper exploration

of the related mechanisms and genetic factors.

Keywords

Post-COVID-19, Vasculature, Molecular mechanisms, Vascular damage, Endothelial

Abbreviations

AF: Atrial Fibrillation; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease-19; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; ET-1: Endothelin 1; NFE2L1: Erythroid-2 like 1; ISS: Ischemic Stroke; NETs: Neutrophil Extracellular Traps; PAH: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension; PRSs: Polygenic Risk Scores; PKC: Proteinase K; SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; VTE: Venous Thromboembolism

Introduction

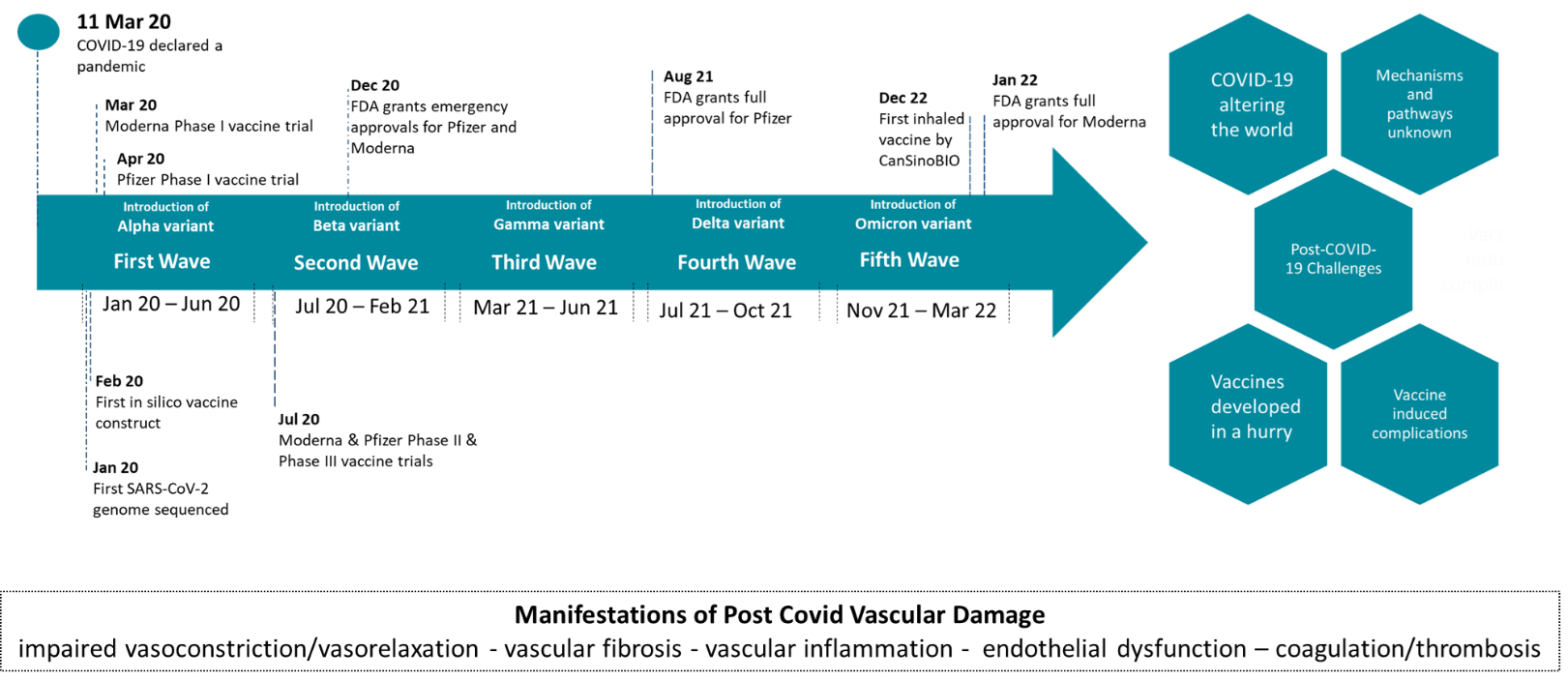

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has changed significantly with new challenges constantly arising (Figure 1) [1]. One of the main challenges is the increased prevalence of a prolonged post-COVID-19 syndrome, widely known as "Post COVID", which is currently regarded as a public health issue worldwide [2].

Figure 1: Timeline of COVID-19 progression and vaccine development [49-51]. The Figure shows post-COVID-19 associated challenges and highlights the need for molecular and pathway studies.

To date, there is no standardized definition of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome [2,3]. Although the definition is still evolving, it can be described as a condition in which individuals experience persistent symptoms or complications lasting beyond 30 days following SARS-COV-2 infection [2,4].

As a multi-faceted syndrome, post COVID affects a variety of different organs and presents a wide array of symptoms. Common manifestations include dyspnea, chest pain, persistent fatigue, loss of taste and/or smell as well as cognitive, gastrointestinal, immunological, and cardiovascular dysfunctions [2,5].

The incidence of Post COVID is marked with substantial heterogeneity across different studies. This heterogeneity can be ascribed to differences in the definitions of Post COVID, the array of symptoms considered as well as the variability in study cohorts’ compositions [2]. Reports indicate that Post COVID may affect anywhere from approximately 30% to more than 80% of individuals who have contracted SARS-CoV-2 [2,6].This wide range underlines the complexity of the Post COVID condition and highlights the need for standardized research for its diagnosis and assessment.

Reducing the risk of developing Post COVID can potentially be achieved via vaccination. However, current research has not definitively confirmed this hypothesis since break-through infections may still cause prolonged COVID complications in vaccinated individuals [7,8]. Additionally, the vaccines themselves can cause serious problems such as myocarditis [9,10]. Therefore, the effect of vaccination on Post COVID needs to be further studied.

To better understand the aforementioned variability of complications, the heterogeneity of affection as well as the effect of vaccination on Post COVID, it is of paramount importance to study its molecular underpinnings. Although the exact mechanisms underlying Post COVID remain largely unknown, several potential factors and pathways have been proposed based on ongoing research including persistent viral presence, organ fibrosis, immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, neurological effects, mitochondrial dysfunction, and epigenetic changes [1,11-14].

In addition to these pathways, mechanisms of microvascular pathology have been ascribed to Post COVID, especially in cases where imaging techniques fail to correlate persistent Post COVID symptoms such as dyspnea and fatigue with the degree of lung damage [1,15].

The concept of latent microvascular pathology playing a pivotal role in Post COVID is gaining traction, especially since there is a significant association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and endothelial as well as systemic vascular dysfunction [16-18]. Signs of vascular wall edema, hyaline thrombi, microhemorrhages, and widespread thrombosis in small peripheral blood vessels are frequently present alongside lung and other organ damage in patients with severe COVID-19 [16,19,20]. A potential explanation for such vascular damage could be the high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines circulating in patients with severe COVID-19 [16,21]. This is commonly referred to as cytokine storm and is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 [18,22,23]. Taken together, severe COVID-19 can manifest as a condition characterized by excessive inflammation, increased blood clot formation, and widespread engagement of multiple organs, impacting the entirety of the vascular system [16,24].

Systemic vascular dysfunction is also implicated in Post COVID [25,26]. This systemic involvement implies that Post COVID is not solely a respiratory issue but a complex condition affecting various bodily systems. The lack of clarity regarding the mechanisms involved has made the treatment of Post COVID imprecise, emphasizing the need for extensive research and a multidisciplinary approach to addressing this syndrome [25,26]. Prioritizing the prevention of serious vascular complications is crucial to Post COVID-19 patient management. However, a significant challenge remains in accurately pinpointing individuals who are at risk and would gain from close monitoring or tailored pharmacological preventive measures.

We here provide a unifying overview of existing literature, focusing on the role of vascular dysfunction in post-COVID conditions, along with insights into the putative mechanisms including genetics.

Main Body

Vascular dysfunction in Post COVID

Vascular dysfunction induced by SARS-CoV-2 infections is a result of the induction of a severe inflammatory reaction (cytokine storm) which sets off a chain reaction involving the activation of a coagulation cascade causing various thrombotic complications where blood clots impede blood flow to various vital organs [22,24,27]. This intensified activation of the innate immune system coupled with the release of substantial quantities of substances in the blood stream triggering vascular inflammation results in increasing the severity of COVID-19 pathology [22,24,27].

Only a limited number of studies with small cohort sizes have examined the extended systemic vascular consequences of COVID-19. Studies on deceased COVID-19 patients revealed thromboembolisms in both arteries and veins, necessitating additional research to confirm a direct connection to SARS-CoV-2 infection [24]. In a study involving 10 COVID-19 patients experiencing symptoms for more than 30 days compared to controls, elevated target-to-blood pool ratios were observed in several vascular regions, suggesting persistent vascular inflammation [28]. In other studies, COVID-19 patients 3–4 weeks post-infection exhibited diminished systemic vascular function and greater arterial stiffness compared to controls [29,30]. Three months after a COVID-19 diagnosis, another study showed that young adults experiencing ongoing symptoms exhibited notable decreases in peripheral macrovascular and microvascular vasodilation when compared to healthy controls [31].

Post-COVID-related vascular problems may indicate possible endothelial dysfunction. Viral RNA presence is confirmed in endothelial cells via single-cell RNA sequencing for months post-diagnosis and is associated with vascular impairment, endothelial cell activation and inflammation [2]. Recovered COVID-19 patients exhibit elevated circulating endothelial counts and increased von Willebrand factor and D-dimer levels indicating sustained endothelial activation [2]. This is confirmed by another study which examined the 1-month impact of COVID-19 on endothelial function by comparing 20 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with 12 controls [25]. In this study, isolated instances of stress-induced cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, and acute coronary syndrome were detected during hospitalization and elevated D-dimer levels were persistent one month after discharge indicating sustained impaired endothelial function in Post COVID [25]. In another study with 50 patients, conducted 68 days after obtaining a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, it was found that endothelial cell activation continued for up to 10 weeks regardless of any ongoing acute phase response or the creation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [32]. Instead, it was associated with increased thrombin generation [32]. Epigenetic changes in endothelial cells could also be induced by viruses, hypoxia, or inflammation associated with COVID-19 and need to be further studied [2].

Vascular and endothelial dysfunction may lead to altered heart rate and blood pressure which may explain exercise intolerance associated with Post COVID [33-35]. In a study with 18 COVID-19 patients (9 symptomatic, 9 asymptomatic) and 9 controls, only those with previous symptomatic COVID-19 exhibited blunted heart rate and blood pressure variability associated with poor parasympathetic nervous system and cardiovascular health [36,37]. Autonomic pathways might be implicated [31]. Other post-COVID-19 cardiovascular complications include chest pain, palpitations, arrhythmia, tachycardia, and myocarditis, of which many require further studies to confirm their persistence in post-COVID [24,27,38-40]. Severe inflammation and/or direct viral attack on the heart are amongst the possible mechanisms for such complications, which may be pronounced in younger patients who received the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine [27,37].

COVID-19-induced pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) developed post-COVID-19 may be a result of the infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus [1,16,41,42]. Endothelin 1 (ET-1) plays a well-studied role in the development of PAH causing vascular remodeling via its proliferative, fibrotic, and prothrombotic effects [43,44]. Upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, the upregulation of ET-1 may induce a pulmonary vascular condition resembling PAH and thus can be treatable with endothelin blockers like ambrisentan (selective ETAR antagonist) or bosentan/macitentan (dual receptors blocker), which are known to improve outcomes in PAH [45]. Additionally, high levels of circulating ET-1 or the existence of ET-1 gene variations may serve as crucial biomarkers for identifying individuals at risk of developing COVID-19-induced PAH [1].

Genetics and post-COVID vascular dysfunction

In light of the previously discussed vascular complications, it is essential to examine the clinical and genetic factors that increase the vulnerability of post-COVID-19 patients to vascular pathologies.

In a study involving 18,818 COVID-19 patients compared to 93,179 matched uninfected controls without prior venous thromboembolism (VTE), SARS-CoV-2 infection was linked to an increased VTE risk within 1 month of COVID-19 positivity [46]. However, this risk was significantly decreased among fully vaccinated individuals even with breakthrough infections, which may address concerns regarding vaccines and thromboembolic events that led to hesitancy in their use [46,47]. Independent clinical risk factors for COVID-19-associated VTE included older age, male gender, obesity, no or partial vaccination as well as inherited thrombophilia [46]. Among the genetic factors, factor V Leiden thrombophilia doubled the VTE risk and inherited thrombophilia had a 2.05 hazard ratio for post-COVID-19 VTE [46]. This underscores the potential role of factor V and consequently possibly prothrombin proteins in post-COVID-19 VTE and supports the idea of VTE prevention through targeted genetic screening for thrombophilia in older infected individuals [46].

In a different study, a prospective cohort from the UK Biobank, comprising 25,335 participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, was used to investigate outcomes such as atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary artery disease (CAD), ischemic stroke (ISS), and VTE within 3 months after infection [48]. During the acute phase of COVID-19, polygenic risk scores (PRSs) were associated with a progressively higher risk of AF, CAD, and VTE, albeit not with ISS [48]. There was no evidence indicating interactions between genetics and lifestyle factors in this study, which further highlights the importance of epigenetic studies of the vasculature post-COVID-19 [48].

Another study comprised of 27 patients 3 months post-COVID compared to 10 controls showed that COVID-19 vessels exhibited increased vasoconstriction and diminished vasorelaxation reflecting the inability of the arteries to expand and contract properly [26]. This abnormal vasoconstriction was attributed to pathological Rho-kinase activation as a consequence of increased phosphorylation of myosin light chain, which in its phosphorylated state, exhibits increased sensitivity to calcium ions which increases the interaction between actin and myosin filaments, ultimately causing increased contractions of vascular smooth muscle cells [26]. Whole transcriptome analysis in this study revealed expected upregulation of myosin light chain and downregulation of proteinase K (PKC) [26]. Additionally, it showed increased expression of genes like nuclear factor erythroid-2 like 1 (NFE2L1) and glutathione peroxidase 3, involved in regulating oxidative stress and inflammation, of the DCN gene responsible for decorin synthesis, of the matrix gla protein gene involved in disruptions of calcium ion balance and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [26]. Gene ontology analysis showed that processes such as viral replication, platelet activation, connective tissue organization, and tissue morphogenesis were upregulated and gene pathway analysis identified pathways involving ECM regulation and ECM proteoglycans, which are implicated in vascular fibrosis and VSMC dysfunction [26].

Conclusion

In conclusion, Post COVID is a complex condition with diverse vascular complications, highlighting the importance of molecular research in larger cohorts over an extended period of time to differentiate chronic disease manifestations from symptoms that might be resolved after 3-12 months. The research must include molecular and epi/genetic aspects, to improve diagnosis, prevention, and management. Addressing vascular dysfunction is crucial to mitigate post COVID's impact on affected individuals' quality of life.

References

2. De Rooij LPMH, Becker LM, Carmeliet P. A Role for the Vascular Endothelium in Post-Acute COVID-19? Circulation. 2022 May 17;145(20):1503-5.

3. Haslam A, Olivier T, Prasad V. The definition of long COVID used in interventional studies. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023 Aug 1;53(8):e13989.

4. Baimukhamedov C. How long is long COVID. Int J Rheum Dis. 2023 Feb 1;26(2):190-2.

5. Altmann DM, Whettlock EM, Liu S, Arachchillage DJ, Boyton RJ. The immunology of long COVID. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023 Oct;23(10):618-34.

6. Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID Syndrome: Incidence, Clinical Spectrum, and Challenges for Primary Healthcare Professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021 Aug;52(6):575-581.

7. Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Velasco JV, Pastrana A, Ver AT, Pangilinan FC, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101624.

8. Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, Lustig Y, Balicer RD. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022 Jan;22(1):57-65.

9. Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson I V., Robicsek A. Myocarditis and Pericarditis After Vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021 Sep 28;326(12):1210-2.

10. Sirufo MM, Raggiunti M, Magnanimi LM, Ginaldi L, De Martinis M. Henoch-schönlein purpura following the first dose of covid-19 viral vector vaccine: A case report. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1078.

11. Leng A, Shah M, Ahmad SA, Premraj L, Wildi K, Li Bassi G, et al. Pathogenesis Underlying Neurological Manifestations of Long COVID Syndrome and Potential Therapeutics. Cells. 2023 Mar 6;12(5):816.

12. Cheong JG, Ravishankar A, Sharma S, Parkhurst CN, Nehar-Belaid D, Ma S, et al. Epigenetic Memory of COVID-19 in Innate Immune Cells and Their Progenitors. Cell. 2023 Aug 31;186(18):3882-02.e24.

13. Sherif ZA, Gomez CR, Connors TJ, Henrich TJ, Reeves WB, Pathway M, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Elife. 2023 Mar 22:12:e86002.

14. Astin R, Banerjee A, Baker MR, Dani M, Ford E, Hull JH, et al. Long COVID: mechanisms, risk factors and recovery. Exp Physiol. 2023 Jan 1;108(1):12–27.

15. Østergaard L. SARS CoV-2 related microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19: Consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Physiol Rep. 2021 Feb;9(3):e14726.

16. Halawa S, Pullamsetti SS, Bangham CRM, Stenmark KR, Dorfmüller P, Frid MG, et al. Potential long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the pulmonary vasculature: a global perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022 May;19(5):314-31.

17. Huertas A, Montani D, Savale L, Pichon J, Tu L, Parent F, et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction: A major player in SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19)? . Vol. 56, European Respiratory Journal. Eur Respir J. 2020 Jul 30;56(1):2001634.

18. Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 9;383(2):120-8.

19. Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, Rossi RS, Pellegrinelli A, Zerbi P, et al. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Oct 1;20(10):1135-40.

20. Fox SE, Akmatbekov A, Harbert JL, Li G, Quincy Brown J, Vander Heide RS. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Jul 1;8(7):681–6.

21. Gao YD, Ding M, Dong X, Zhang JJ, Kursat Azkur A, Azkur D, et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: A review. Allergy. 2021 Feb;76(2):428-55.

22. Levi M, Coppens M. Vascular mechanisms and manifestations of COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Jun 1;9(6):551.

23. Moccia F, Gerbino A, Lionetti V, Miragoli M, Munaron LM, Pagliaro P, et al. COVID-19-associated cardiovascular morbidity in older adults: a position paper from the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Researches. Geroscience. 2020 Aug 1;42(4):1021.

24. Martínez-Salazar B, Holwerda M, Stüdle C, Piragyte I, Mercader N, Engelhardt B, et al. COVID-19 and the Vasculature: Current Aspects and Long-Term Consequences. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Feb 15;10:824851.

25. Lampsas S, Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Souvaliotis N, Goliopoulou A, Mistakidi C V, et al. Mid-term endothelial dysfunction post COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(Suppl 1):ehab724.3401.

26. Sykes RA, Neves KB, Alves-Lopes R, Caputo I, Fallon K, Jamieson NB, et al. Vascular mechanisms of post-COVID-19 conditions: Rho-kinase is a novel target for therapy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2023 Jun 2;9(4):371-86.

27. Andrade BS, Siqueira S, Rodrigues W, Soares A, De Souza Rangel F, Santos NO, et al. Long-COVID and Post-COVID Health Complications: An Up-to-Date Review on Clinical Conditions and Their Possible Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses. 2021;13:700.

28. Sollini M, Ciccarelli M, Cecconi M, Aghemo A, Morelli P, Gelardi F, et al. Vasculitis changes in COVID-19 survivors with persistent symptoms: an [18F]FDG-PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 May;48(5):1460-6.

29. Szeghy RE, Province VM, Stute NL, Augenreich MA, Koontz LK, Stickford JL, et al. Carotid stiffness, intima–media thickness and aortic augmentation index among adults with SARS-CoV-2. Exp Physiol. 2022 Jul;107(7):694-707.

30. Ratchford SM, Stickford JL, Province VM, Stute N, Augenreich MA, Koontz LK, et al. Vascular alterations among young adults with SARS-CoV-2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021; 320(1):H404-H410.

31. Nandadeva D, Young BE, Stephens BY, Grotle AK, Skow RJ, Middleton AJ, et al. Blunted peripheral but not cerebral vasodilator function in young otherwise healthy adults with persistent symptoms following COVID-19. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;321(3): H479-H484.

32. Fogarty H, Townsend L, Morrin H, Ahmad A, Comerford C, Karampini E, et al. Persistent endotheliopathy in the pathogenesis of long COVID syndrome. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2021 Oct;19(10):2546-53.

33. Nader M, Haddad G, Elies J, Kentamneni S, AlBadarin F. Editorial: Trends post-COVID-19 attack: the cardiocerebral system safety remains of utmost concern. Front Physiol. 2023 Jul 11:14:1224550.

34. Ojeda DA, Shamsi MM, Mora J, Tobar J, Aparisi Á, Ladrón R, et al. Exercise Intolerance in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 and the Value of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing-a Mini-Review. Front Med. 2022;1:924819.

35. Edward JA, Peruri A, Rudofker E, Shamapant N, Parker H, Cotter R, et al. Characteristics and Treatment of Exercise Intolerance in Patients With Long COVID. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2023 Nov 1;43(6):400-6.

36. Chan J, Senior H, Homitz J, Cashin N, Guers JJ. Individuals with a previous symptomatic COVID-19 infection have altered heart rate and blood pressure variability during acute exercise. Front Physiol. 2023 Feb 6;14:1052369.

37. Gonzalez-Gonzalez FJ, Ziccardi MR, McCauley MD. Virchow’s Triad and the Role of Thrombosis in COVID-Related Stroke. Front Physiol. 2021 Nov 10;12:769254.

38. Chudzik M, Lewek J, Kapusta J, Banach M, Jankowski P, Bielecka-Dabrowa A. Predictors of Long COVID in Patients without Comorbidities: Data from the Polish Long-COVID Cardiovascular (PoLoCOV-CVD) Study. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 25;11(17):4980.

39. Raman B, Bluemke DA, Lüscher TF, Neubauer S. Long COVID: Post-Acute sequelae of COVID-19 with a cardiovascular focus. Eur Heart J. 2022 Mar 14;43(11):1157-72.

40. Chilazi M, Duffy EY, Thakkar A, Michos ED. COVID and Cardiovascular Disease: What We Know in 2021. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021 May 13;23(7):37.

41. Ryan JT, de Jesus Perez VA, Ryan JJ. Health Disparities in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adv Pulm Hypertens. 2021;20(1):6-15.

42. Hinojosa W, Cristo-Ropero MJ, Cruz-Utrilla A, Segura de la Cal T, López-Medrano F, Salguero-Bodes R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pulmonary hypertension: What have we learned? Pulm Circ. 2022 Oct 1;12(4):e12142.

43. Dupuis J, Cernacek P, Tardif JC, Stewart DJ, Gosselin G, Dyrda I, et al. Reduced pulmonary clearance of endothelin-1 in pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J. 1998 Apr;135(4):614-20.

44. Chester AH, Yacoub MH. The role of endothelin-1 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014 Jun 18;2014(2):62-78.

45. Shao D, Park JES, Wort SJ. The role of endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pharmacol Res. 2011 Jun;63(6):504-11.

46. Xie J, Prats-Uribe A, Feng Q, Wang Y, Gill D, Paredes R, et al. Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Acute Incident Venous Thromboembolism in Ambulatory Patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(10):1063-70.

47. Mahase E. Covid-19: US suspends Johnson and Johnson vaccine rollout over blood clots. BMJ. 2021 Apr 13:373:n970.

48. Xie J, Feng Y, Newby D, Zheng B, Feng Q, Prats-Uribe A, et al. Genetic risk, adherence to healthy lifestyle and acute cardiovascular and thromboembolic complications following SARS-COV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2023 Dec 1;14(1):4659.

49. Chakraborty C, Bhattacharya M, Dhama K. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines, Vaccine Development Technologies, and Significant Efforts in Vaccine Development during the Pandemic: The Lessons Learned Might Help to Fight against the Next Pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Mar 17;11(3):682.

50. Peterson CJ, Lee B, Nugent K. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers—A Review. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jun 15;10(6):948.

51. Gao L, Zheng C, Shi Q, Xiao K, Wang L, Liu Z, et al. Evolving trend change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022 Sep 20:10:957265.