Abstract

The history of cancer therapeutics since its birth some eighty years ago has gone through a tortuous path guided by understanding of the mechanism of carcinogenesis and notorious for many excitements and frustrations [1]. The birth of nitrogen mustard in 1940’s through a serendipitous observation during the Second World War, was guided by the perception that a poison that kills normal cells, could also kill cancer cells [2]. The excitement generated by shrinkage of tumor mass was soon followed by disappointment and frustration caused by tumor regrowth [3]. One could see more or less the same pattern as we moved to multi-agent chemotherapy protocols, targeted therapy, high intensity chemotherapy with or without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunotherapy [4]. As our understanding evolved into growth, proliferation, and intracellular communication pathways, our definition of cancer also shifted from the generic uncontrolled proliferation to disorder of genome, apoptosis and immortality through telomere dysfunction [5]. Today, the evolution of thinking is taking us towards breakdown of fundamental laws that govern normal cellular homeostasis as the core mechanism of neoplastic transformation [6]. This evolution of understanding alongside major advances in other areas such as single cell sequencing and nano-technology, would enable us to open a new chapter in history of cancer therapeutics [7].

Cancer Therapy Evolution Step Stones

1- Nitrogen mustard in 1940’s is the result of a serendipitous discovery during the Second World War

This gave birth to this alkylating agent and its use in pediatric lymphoma [8]. Its use generated a lot of excitement which was soon followed by frustration due to tumor regrowth.

2- Fluorinated pyrimidines in 1950’s

Scientific experiments on hepatoma cell lines by Heidelberger gave birth to 5-FU, which is in use some 80 years later [9].

3- Platinum compounds in 1970’s

Another serendipitous discovery, this time by Einhorn, brought Cis-platinum into the treatment protocols of testicular cancer, leading to a breakthrough in its treatment and outcome [10].

4- Tamoxifen and Taxol of 1970s-1990s

Above agents represent the birth of targeted therapeutic and naturally occurring Compounds [11]. NCI of USA had around thirty thousand naturally occurring compounds on its shelf. Taxol and a lot of other naturally occurring compounds were among them.

Meanwhile, growth, proliferation and transduction pathways started to become targets of the next generation of cancer therapeutics. From this point on, explosion of knowledge in cancer biology and deeper understanding of living cell at DNA, RNA, Micro-RNA, Epigenome, Telomere, Gene regulatory pathways [12], Tumor Suppressor genes, Oncogenes, and Tumor Immunology [13] took the driver’s seat and led to yet another generation of cancer Therapeutic agents. Findings on microenvironment and tumor vasculature, and their interplay with tumor mass led to major breakthroughs such as development of Imids and Inhibitors of tumor vasculature such as Avastin [14].

Fundamental Change in Understanding of Neoplastic Transformation, as the Foundation of the Next Step in Evolution of Cancer Therapeutics

In the last eighty years, cancer has been defined in many different ways, ranging from disorderly proliferation of dedifferentiated cells to disease of genome. Numerous changes in cancer definition and treatment in different eras has followed evolution in understanding the process of carcinogenesis [15].

Of interest, in the last eighty years we have continued to evolve into more sophisticated cancer cell killers [16]. This implies that we have continued to believe that we should kill cancer cells to cure our patients [17]. However, exceptions such as Imids [18] and differentiating agents such as Retinoids [19] that interfere with microenvironmental growth and survival signals as well as intracellular transduction pathways exist [20].

Regardless, for the most part we are dealing with insurmountable barriers. It is clear that we need to come up with true definition of cancer [21], in order to develop a solid foundation for development of next generation of cancer therapeutics [22]. This necessitates deep understanding of the interplay of the most fundamental law [23] that governs the homeostasis of living cell, namely the second law of thermodynamics [24], with cell function at all levels, including its birth, proliferation, and demise. The main reason for failure and limited success of numerous generations of cancer therapeutics so far, is that they have been built on a false or partial understanding of neoplastic transformation [25]. To avoid a similar destiny, we need to take one big step back and examine the real mechanism of initiation of mitosis [26] during different eras of life cycle of an organism, dating back to first mitosis following fertilization [27].

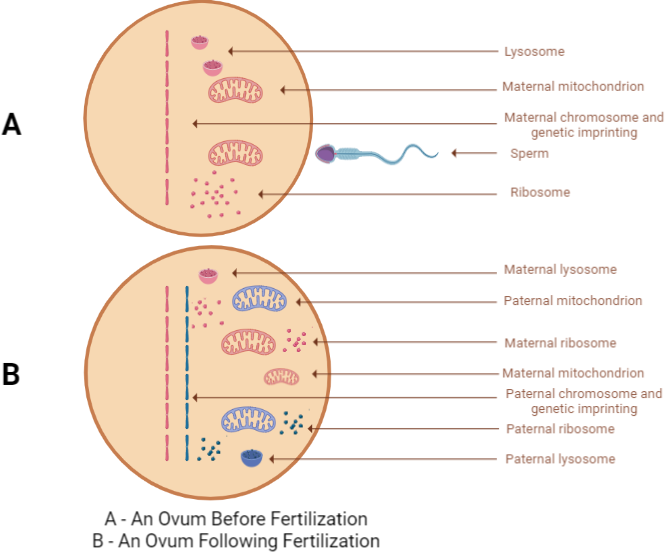

As far as the governing universal laws are concerned, two major events incessantly ensue fertilization, 1- crowding through addition of another 23 chromosomes to the closed space of ovum, 2- addition of totally unfamiliar paternal genetic imprinting to that of the maternal genetic imprinting of ovum (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Following fertilization: 1 - Crowding, 2 - Addition of paternal genetic imprinting [unwanted information]

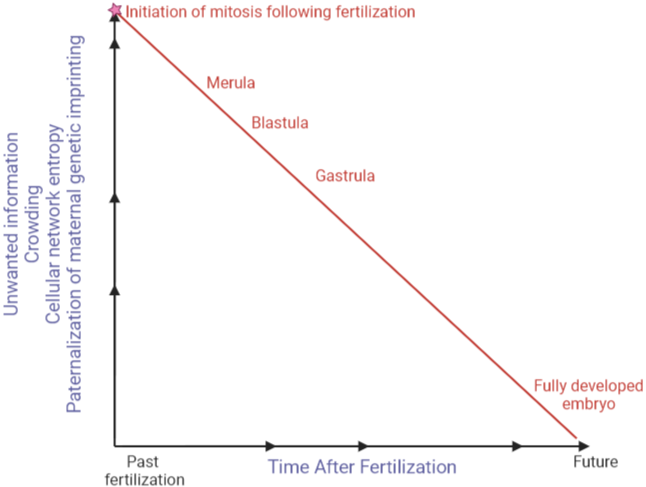

Both of these two events significantly increase the cellular network entropy in no time [28]. As such, the second law of thermodynamics which is flowing in the matrix of living cell, gets disturbed in the sense that the foundation of living cell which is based on keeping the cellular network entropy at the lowest, is shaken. This disturbance, in a puzzling way leads to initiation of mitosis. This is akin to eruption of a volcano. The only goal of recurrent rounds of mitosis following fertilization [29] is minimizing the cellular network entropy, by materialization of paternal genomic imprinting more and more with each round of mitosis [30], and generating a new normal state by populating numerous cells and organ formation with the same number of chromosomes during embryogenesis. Available studies have shown further materialization of paternal genomic imprinting following each round of mitosis [31]. Destruction of paternal mitochondrion immediately following fertilization and loss of Y chromosome in males as they age lend further support to this concept [32]. A lot of disorders that we get afflicted with are the result of breakdown [33] of above-mentioned path (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dramatic increase in cellular network entropy of fertilized ovum triggers mitosis. At the time of fertilization, crowding happens and massive amount of unwanted information also enters ovum. Recurrent rounds of mitosis [embryogenesis] aims at maternalization of paternal genetic Imprinting and massive organization, i.e. significant decrease of cellular and organism networks entropy.

To protect the integrity of the living cell and to keep the cellular network entropy at the minimum possible level as per the limit of the second law, evolution of living organisms has developed sensors [34] and executors [35] at each and every subcellular compartment of the cell. According to Murphy’s law [36], what could go wrong would go wrong. A diverse group of disease states are the result of dysfunction of sensors and executors [37]. In this regard, cancer is the prototype example. The net result is a significant increase in cellular network entropy in a very short period of time. Available mathematical models could measure master regulator network entropy of cell which represents above premises [38].

In contradistinction to cancer, cellular network entropy of an aged cell gets elevated over a matter of several decades [39]. That is why the vast majority of cancers are diagnosed in older people [40]. Consequently, true definition of cancer is neither uncontrolled proliferation of dedifferentiated cells, nor is it the disease of the genome [41]. Rather they are different manifestations of the breakdown of the fine interplay of the second law of thermodynamics with the living cell, which leads to massive increase in cellular network entropy in a very short period of time. This massive increase in entropy affects all the sub-compartments of the cell ranging from quaternary structure of cellular proteins [42] to micro-RNA network and epigenome [43]. One major reason, why despite the fact that in midlife cells of different organs are loaded with ill mutations, cancer is not prevalent [44], is the fact that cellular network entropy has not reached a critical level as yet.

Future Cancer Therapeutics Strategy Based on Reversal of Cellular Network Entropy

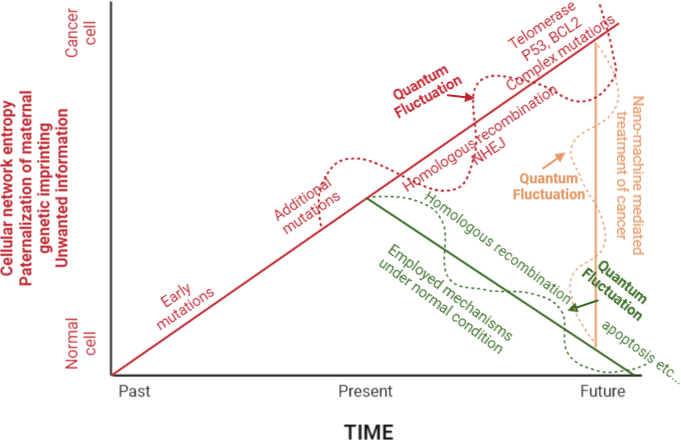

Single cell sequencing technology [45], and existing mathematical models for calculation of master regulator complex network entropy, could enable us to derive spatial entropyomics [46] signature of evolutionary road map of tumor mass. As the forward evolutionary path of tumor mass along the thermodynamics arrow of time happens in quanta, each step in this forward move is guided by a new driver.

Consequently, there are numerous drivers along this path [47], in contradistinction to the current thinking of one driver, one cancer. The driver front is expected to have the highest master regulator complex network entropy. By using artificial Intelligence [48], one could predict the future of tumor mass, and take pre-emptive steps to slow down or block the forward evolutionary tumor road map.

Nanotechnology [49], and available nanodelivery methodologies, could enable us to modify the current and future driver front master regulator complex network entropy, and bring them close to the values of previous generation of drivers. As such, the forward move of tumor mass would cease or significantly slow down.

At times our nanomachines have to deliver a missing micro-RNA to the driver front [50], and on some occasions they would change the transmembrane electrostatic force [51].

These decisions need to be made by a team of scientists comprised by single cell sequencers [52], evolutionary biologists, mathematical biologists, and artificial intelligence specialists, in a customized fashion (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Normal mechanisms employed in reversal of neoplastic transformation and their breakdown leading to full blown neoplastic transformation. Quantam flucation refers to a non-smooth path, based on quantam nature of living cell. Nano machines could get designed in a diverse group of ways, to acheive the task of reversal or freeze of the evolutionary forward move of tumor mass.

Conclusion

We have gone a long way since the introduction of nitrogen mustard as the first cancer treatment regimen in 1942. Multiagent chemotherapy protocols, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, monoclonal antibodies, tumor vaccines, differentiating agents, microenvironment modifiers, antivascular agents, and the new generation of immunotherapy, comprise different chapters of this long journey. Each, guided by new findings, discoveries, and dominant thinking of forefront thinkers of cancer medicine field. Each, celebrated with joy, and tarnished by disappointments. Each era characterized and shaped by a different type of understanding of the underlying mechanism of neoplastic transformation.

We have reached a point in this journey, that a deep and true understanding of the underlying mechanism of neoplastic transformation is needed more than ever before. Such understanding would revolutionize cancer therapy, and take our despairs away.

Breakdown of the fine interplay of the second law of thermodynamics with the living cell, and its different manifestations in numerous disease states, most specifically cancer, alongside advances in single cell sequencing, evolutionary biology, mathematical biology models, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence, would offer us a unique and historical opportunity to turn cancer into one of the many chronic disorders.

References

2. Einhorn J. Nitrogen mustard: the origin of chemotherapy for cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 1985 Jul 1;11(7):1375-8.

3. Skipper HE. Kinetics of mammary tumor cell growth and implications for therapy. Cancer. 1971 Dec;28(6):1479-99.

4. FREI III EM, Karon M, Levin RH, FREIREICH EJ, Taylor RJ, Hananian J, et al. The effectiveness of combinations of antileukemic agents in inducing and maintaining remission in children with acute leukemia. Blood. 1965 Nov;26(5):642-56.

5. Fan HC, Chang FW, Tsai JD, Lin KM, Chen CM, Lin SZ, et al. Telomeres and cancer. Life. 2021 Dec 16;11(12):1405.

6. West J, Bianconi G, Severini S, Teschendorff AE. Differential network entropy reveals cancer system hallmarks. Scientific Reports. 2012 Nov 13;2(1):1-8.

7. Morash M, Mitchell H, Beltran H, Elemento O, Pathak J. The role of next-generation sequencing in precision medicine: a review of outcomes in oncology. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2018 Sep 17;8(3):30.

8. Christakis P. Bicentennial: the birth of chemotherapy at yale: bicentennial lecture series: surgery grand round. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2011 Jun;84(2):169-72.

9. Heidelberger C, Chaudhuri NK, Danneberg P, Mooren D, Griesbach L, Duschinsky R, et al. Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds. Nature. 1957 Mar 30;179(4561):663-6.

10. Einhorn LH, Donohue J. Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, vinblastine, and bleomycin combination chemotherapy in disseminated testicular cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1977 Sep 1;87(3):293-8.

11. Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. Isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1971 May;93(9):2325-7.

12. Davidson EH, Levine MS. Properties of developmental gene regulatory networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008 Dec 23;105(51):20063-6.

13. Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Nature. 2017 Jan 19;541(7637):321-30.

14. Ferrara N, H Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646-74. illan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004 May 1;3(5):391-400.

15. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646-74.

16. Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Lessons learned from the development of an abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myelogenous leukemia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000 Jan 1;105(1):3-7.

17. Guan X. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2015 Sep 1;5(5):402-18.

18. Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H. Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science. 2010 Mar 12;327(5971):1345-50.

19. Chabon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. The FASEB Journal. 1996 Jul;10(9):940-54.

20. Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002 Dec 6;298(5600):1911-2.

21. Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, Lapinska K, Longacre M, Snyder N, Sarkar S. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers. 2014 Sep 5;6(3):1769-92.

22. Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, Eggermont AM, Schilsky RL, Mendelsohn J, et al. Impact of precision medicine in diverse cancers: a meta-analysis of phase II clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Nov 11;33(32):3817-25.

23. Davies PC, Rieper E, Tuszynski JA. Self-organization and entropy reduction in a living cell. Biosystems. 2013 Jan 1;111(1):1-10.

24. Trevors JT, Saier Jr MH. Thermodynamic perspectives on genetic instructions, the laws of biology and diseased states. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2011 Jan 1;334(1):1-5.

25. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz Jr LA, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013 Mar 29;339(6127):1546-58.

26. Pines J. Cubism and the cell cycle: the many faces of the APC/C. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011 Jul;12(7):427-38.

27. Hara Y, Kimura A. Cell-size-dependent spindle elongation in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Current Biology. 2009 Sep 29;19(18):1549-54.

28. Park Y, Lim S, Nam JW, Kim S. Measuring intratumor heterogeneity by network entropy using RNA-seq data. Scientific reports. 2016 Nov 24;6(1):37767.

29. Manders EM, Kimura H, Cook PR. Direct imaging of DNA in living cells reveals the dynamics of chromosome formation. The Journal of Celll biology. 1999 Mar 8;144(5):813-22.

30. Manandhar G, Schatten H, Sutovsky P. Centrosome reduction during gametogenesis and its significance. Biology of Reproduction. 2005 Jan 1;72(1):2-13.

31. Khosla S, Mendiratta G, Brahmachari V. Genomic imprinting in the mealybugs. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2006;113(1-4):41-52.

32. Guo X, Dai X, Zhou T, Wang H, Ni J, Xue J, Wang X. Mosaic loss of human Y chromosome: what, how and why. Human Genetics. 2020 Apr;139:421-46.

33. Sano S, Horitani K, Ogawa H, Halvardson J, Chavkin NW, Wang Y, et al. Hematopoietic loss of Y chromosome leads to cardiac fibrosis and heart failure mortality. Science. 2022 Jul 15;377(6603):292-7.

34. Ali MM, Kang DK, Tsang K, Fu M, Karp JM, Zhao W. Cell‐surface sensors: lighting the cellular environment. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2012 Sep;4(5):547-61.

35. Cheng F, Liu C, Shen B, Zhao Z. Investigating cellular network heterogeneity and modularity in cancer: a network entropy and unbalanced motif approach. BMC Systems Biology. 2016 Aug;10(3):301-11.

36. Spark NT. A history of Murphy's law. Lulu. com; 2006.

37. Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008 Nov 7;322(5903):881-8.

38. Dogra P, Butner JD, Chuang YL, Caserta S, Goel S, Brinker CJ, et al. Mathematical modeling in cancer nanomedicine: a review. Biomedical Microdevices. 2019 Jun;21:40.

39. Luo L, Molnar J, Ding H, Lv X, Spengler G. Physicochemical attack against solid tumors based on the reversal of direction of entropy flow: an attempt to introduce thermodynamics in anticancer therapy. Diagnostic Pathology. 2006 Dec;1:43.

40. Aunan JR, Cho WC, Søreide K. The biology of aging and cancer: a brief overview of shared and divergent molecular hallmarks. Aging and Disease. 2017 Oct;8(5):628-42.

41. Ushijima T, Clark SJ, Tan P. Mapping genomic and epigenomic evolution in cancer ecosystems. Science. 2021 Sep 24;373(6562):1474-9.

42. Li J, Hou C, Ma X, Guo S, Zhang H, Shi L, Liao C, Zheng B, Ye L, Yang L, He X. Entropy-enthalpy compensations fold proteins in precise ways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Sep 6;22(17):9653.

43. Nijman SM. Perturbation-driven entropy as a source of cancer cell heterogeneity. Trends in Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;6(6):454-61.

44. Bond DR, Uddipto K, Enjeti AK, Lee HJ. Single-cell epigenomics in cancer: charting a course to clinical impact. Epigenomics. 2020 Apr;12(13):1139-51.

45. Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Parekh S, Reinius B, Guillaumet-Adkins A, Smets M, et al. Comparative analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing methods. Molecular Cell. 2017 Feb 16;65(4):631-43.

46. Afrasiabi K. Spatial entropyomics: The path to future cancer therapeutics. Journal of Cancer. 2022;3(2):50-4.

47. Sidow A, Spies N. Concepts in solid tumor evolution. Trends in Genetics. 2015 Apr 1;31(4):208-14.

48. Long W, Li Q, Zhang J, Xie H. Identification of key genes in the tumor microenvironment of lung adenocarcinoma. Medical Oncology. 2021 Jul;38(7):83.

49. Chaturvedi VK, Singh A, Singh VK, Singh MP. Cancer nanotechnology: a new revolution for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Current Drug Metabolism. 2019 May 1;20(6):416-29.

50. Chen T, Ren L, Liu X, Zhou M, Li L, Xu J, et al. DNA nanotechnology for cancer diagnosis and therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018 Jun 5;19(6):1671.

51. Song W, Anselmo AC, Huang L. Nanotechnology intervention of the microbiome for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology. 2019 Dec;14(12):1093-103.

52. Grodzinski P, Kircher M, Goldberg M, Gabizon A. Integrating nanotechnology into cancer care. 2019 Jul 23;13(7):7370-7376.