Abstract

Background: Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a simple procedure for a quick cytological diagnosis of suspicious breast lesions. The aim of this study was to evaluate its diagnostic value in our institution.

Methods: It was a hospital-based retrospective cross-sectional study conducted in Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital from 1st January 2019 to 31st December 2023. A total of 93 cases of breast lumps studied with FNAC and compared with their corresponding histological reports were statistically analysed.

Results: The most common age group was 41-50 years. All the cytologically-diagnosed malignant lesions were confirmed malignant on histology but there were three cases of false negative results. The diagnostic accuracy of FNAC was 96.2% and it has a strong correlation with histology (r =0.811, p <0.001).

Conclusion: FNAC has proved to be a useful diagnostic test in evaluating breast lesions in our setting, but its accuracy can still be improved to eliminate false and inconclusive diagnoses.

Keywords

Breast lesions, FNAC, Histology, Diagnostic accuracy

Introduction

Reduction of deaths from breast cancer is currently a top health care priority and an important path of achieving this goal is early detection of the disease [1]. The triple assessment approach which comprises clinical, radiological, and pathological assessment remains an excellent tool in the evaluation of palpable breast lumps. Its diagnostic accuracy exceeds 99% when all three modalities are concordant [2].

Historically, it was a standard practice to perform a diagnostic open biopsy due to the risk of malignancy underdiagnosis [3]. However, Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) and Core Needle Biopsy (CNB) are now universally accepted as methods that eliminate the need for an open biopsy in breast cancer diagnosis. Most countries have now adopted the triple assessment approach to breast cancer diagnosis, with FNAC as a first line pathological investigation in both screening and symptomatic populations, except for cases with microcalcifications [4]. In addition to its high diagnostic accuracy, FNAC offers advantages such as minimal invasiveness, minimal discomfort, cost effectiveness, and rapidity of results when compared with CNB [5]. It is therefore an extremely vital tool in the evaluation of palpable breast lumps in resource-limited settings [6].

Some variations in practice exist when all three assessments are concordant. While some believe that the final treatment of malignant lesions (mastectomy, chemotherapy, and or radiotherapy) may proceed based on FNAC, others insist on a CNB for all index lesions [4]. In most Nigerian hospitals, tissue biopsies are requested before mastectomy even when the lesion is malignant on FNAC, thus increasing the demand on scarce monetary resources [6]. In a resource-constrained setting like ours, a case could be made for proceeding to mastectomy without requesting tissue biopsies, particularly if FNAC is combined with cell block preparations, to further increase its diagnostic accuracy and versatility [6].

Like any other diagnostic test, FNAC possesses some intrinsic and extrinsic disadvantages. It has limitations that can lead to false-negative and false-positive results [7]. The aim of this study therefore is to describe our experience with FNAC in the assessment of breast lumps over a period of five years and to evaluate the diagnostic value in our institution.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and design

It was a hospital-based retrospective cross-sectional study conducted in the departments of Surgery and Anatomic Pathology of Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, a suburban tertiary care centre located in Edo State, South Nigeria. A total of ninety-three (93) available FNAC reports of palpable breast lesions performed between 1st of January 2019 and 31st of December 2023, in patients with clinical diagnoses of cancers or suspicious of cancers, were compared with their corresponding histological reports. All patients who presented with palpable breast lumps and had both FNAC and histology reports were included. Cases with missing data were excluded from the study.

Patients’ demographics, clinical information, and other necessary findings were retrieved from their medical records/ pathology database and recorded on predesigned proforma. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) was performed for all the cases using a 23G needle attached to 10 ml disposable syringes after obtaining informed consent. The aspirate obtained was smeared on standard microscope glass slides, fixed with 95% alcohol for at least 15 minutes, and stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), modified Giemsa, and Papanicolaou (Pap) stains. They were mounted, labelled, dried in hot air oven and thereafter, reported by consultant pathologists. The cytological interpretations were categorized into one of five diagnostic categories following the recommendations of the International Academy of Cytology (IAC) [8]: C1 for inadequate; C2 for benign; C3 for suspicious, probably benign; C4 for suspicious, probably malignant; C5 for malignant breast lesions. Mastectomy was carried out for those reported as C5 and the specimens were sent for histological diagnosis while those with reports of C1-C4 underwent further biopsies for confirmation of malignancy and immunohistochemistry before further management including mastectomy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software version 25 was used. Continuous variables were displayed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while the categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. FNA findings of studied smears were compared with corresponding histology findings obtained with CNB, surgical biopsy, or mastectomy specimens. Both FNAC and histology reports were analysed and correlated. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and diagnostic accuracy were calculated using the following formulas:

Sensitivity= TP/TP+FN X 100

Specificity= TN/TN+FP X 100

PPV= TP/TP+FP X 100

NPV= TN/TN=FN X 100

Diagnostic accuracy= TP+TN X 100/ total cases

TP= True Positive, TN= True Negative, FP= False Positive, FN= False Negative

Results

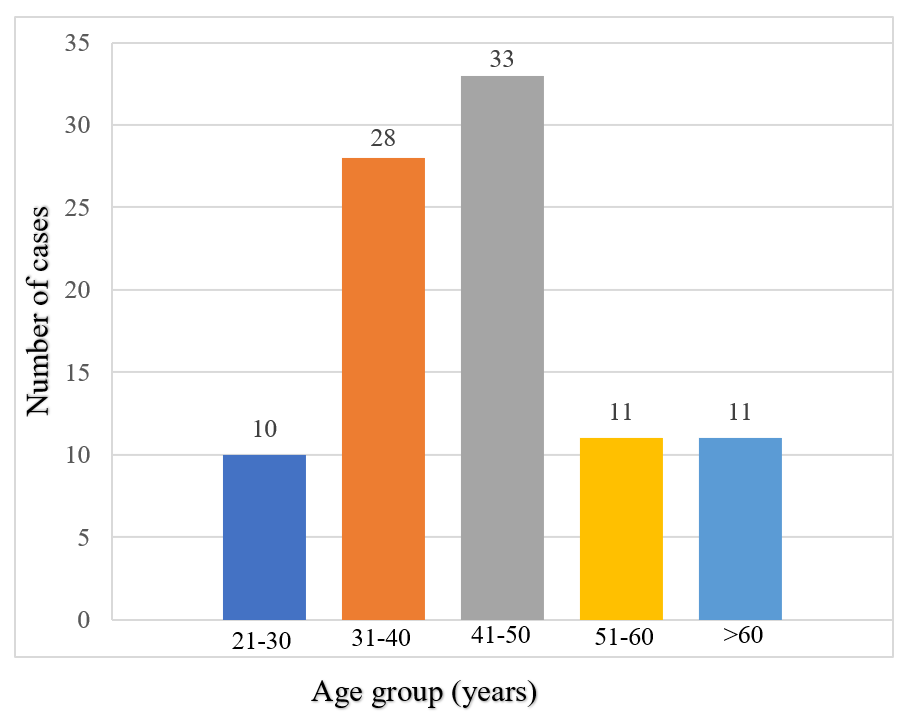

One hundred and sixteen patients had FNAC for suspected breast cancer during the study period but only 93 (80.2%) records with complete data were available for review. The age range of the 93 patients included in this study was 29-70 years with a mean age of 44.3 ± 11.1. The maximum number of neoplasms were seen in the age group of 41-50 years (35.5%), followed by 31-40 years (30.1%) as shown in (Figure 1). There were 90 (96.8%) females and 3 (3.2%) males, resulting in a male to female ratio of 1:30. The right breast was affected in 57 (61.3%) cases and the upper outer quadrant was seen to be the most common quadrant of involvement with 40 cases (43.0%). The sizes of the lumps ranged from 2.0 to 15 cm with 65 (69.9%) patients having lumps greater than 5 cm. Majority of the patients 67 (72.0%) presented with hard lumps while 62 (66.7% of study population) presented with palpable ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes (Table 1).

Figure 1. Age distribution of patients.

|

Characteristics |

Frequency Percentage |

|

|

Site of Lump |

||

|

Bilateral |

2 |

2.2 |

|

Left |

34 |

36.6 |

|

Right |

57 |

61.3 |

|

Quadrant |

||

|

Lower inner quadrant |

3 |

3.2 |

|

Lower outer quadrant |

4 |

4.3 |

|

Central |

26 |

28.0 |

|

Upper inner quadrant |

20 |

21.5 |

|

Upper outer quadrant |

40 |

43.0 |

|

Size of mass |

||

|

2-5 |

28 |

30.1 |

|

>5 |

65 |

69.9 |

|

Consistency |

||

|

Firm |

26 |

28.0 |

|

Hard |

67 |

72.0 |

|

Mobility |

||

|

No |

16 |

17.2 |

|

Yes |

77 |

82.8 |

|

Axillary lymph nodes |

||

|

No |

31 |

33.3 |

|

Yes |

62 |

66.7 |

Sixteen (17.2%) of the patients had breast ultrasound scan, 8 (8.6%) had mammography while 69 (74.2%) did not have any form of breast imaging.

The diagnosis based on FNAC was correlated with histology (Table 2). Sixteen (69.6%) of those with benign results from FNAC also had a benign histology. Among the 19 (20.4%) cases of cytologically benign neoplasms, histology confirmed the benign nature in 16 cases (true negative) while 3 cases turned out to be malignant (false negative). These three FN cases reported as benign (C2) came out as papillary carcinoma, invasive carcinoma NST and mucinous carcinoma on histology. All the cytologically proven malignant neoplasms were confirmed by histology (true positive). In this study, there were no false positive results.

|

Cytological report (n=93) |

n (%) |

Histological report (n) |

Test statistics Pearson’s correlation (r) |

P-value |

|

|

Benign |

Malignant |

||||

|

C1 C2 |

2 (2.2) 19 (20.4) |

0 16 |

2 3 |

0.811 |

<0.001 |

|

C3 C4 |

6 (6.5) 6 (6.5) |

0 0 |

6 6 |

|

|

|

C5 |

60 (64.5) |

0 |

60 |

|

|

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy of FNAC in this study are indicated in (Table 3).

|

Variable |

Value |

95% confidence interval |

|

Sensitivity |

95.24 |

86.71 to 99.01 |

|

Specificity |

100 |

79.41 to 100 |

|

Positive predictive value |

100 |

94.04 to 100 |

|

Negative predictive value |

84.21 |

63.87 to 94.15 |

|

Accuracy |

96.20 |

89.30 to 99.21 |

There was a significant association between age/size of masses and cytological diagnosis. Malignant findings were observed more with increasing age and size of masses (Table 4).

|

Variables |

FNAC |

Test Statistic Chi square (χ2) |

P-value |

||

|

Benign |

(C1, C3, C4) |

Malignant |

|||

|

Age group (years) 21-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 |

4 (40.0) 11 (39.3) 3 (9.1) 1 (9.1) |

2 (20.0) 3 (10.7) 3 (9.1) 2 (18.2) |

4 (40.0) 14 (50.0)) 27 (81.8) 8 (72.7) |

19.939*

|

<0.001

|

|

>60 |

0 (0) |

4 (36.4) |

7 (63.6) |

|

|

|

Location of mass Lower inner quadrant Lower outer quadrant |

1 (33.3) 1 (25.0) |

1 (33.3) 0 (0) |

1 (33.3) 3 (75.0) |

11.373

|

0.175

|

|

Central |

5 (19.2) |

1 (3.8) |

20 (76.9) |

|

|

|

Upper inner quadrant |

2 (10.0) |

2 (10.0) |

16 (80.0) |

|

|

|

Upper outer quadrant |

10 (25.0) |

10 (25.0) |

20 (50.0) |

|

|

|

Size of mass (cm) 2-5 >5 |

16 (57.1) 3 (4,6) |

2 (7.1) 12 (18.5) |

10 (35.7) 50 (76.9) |

33.246 |

<0.001

|

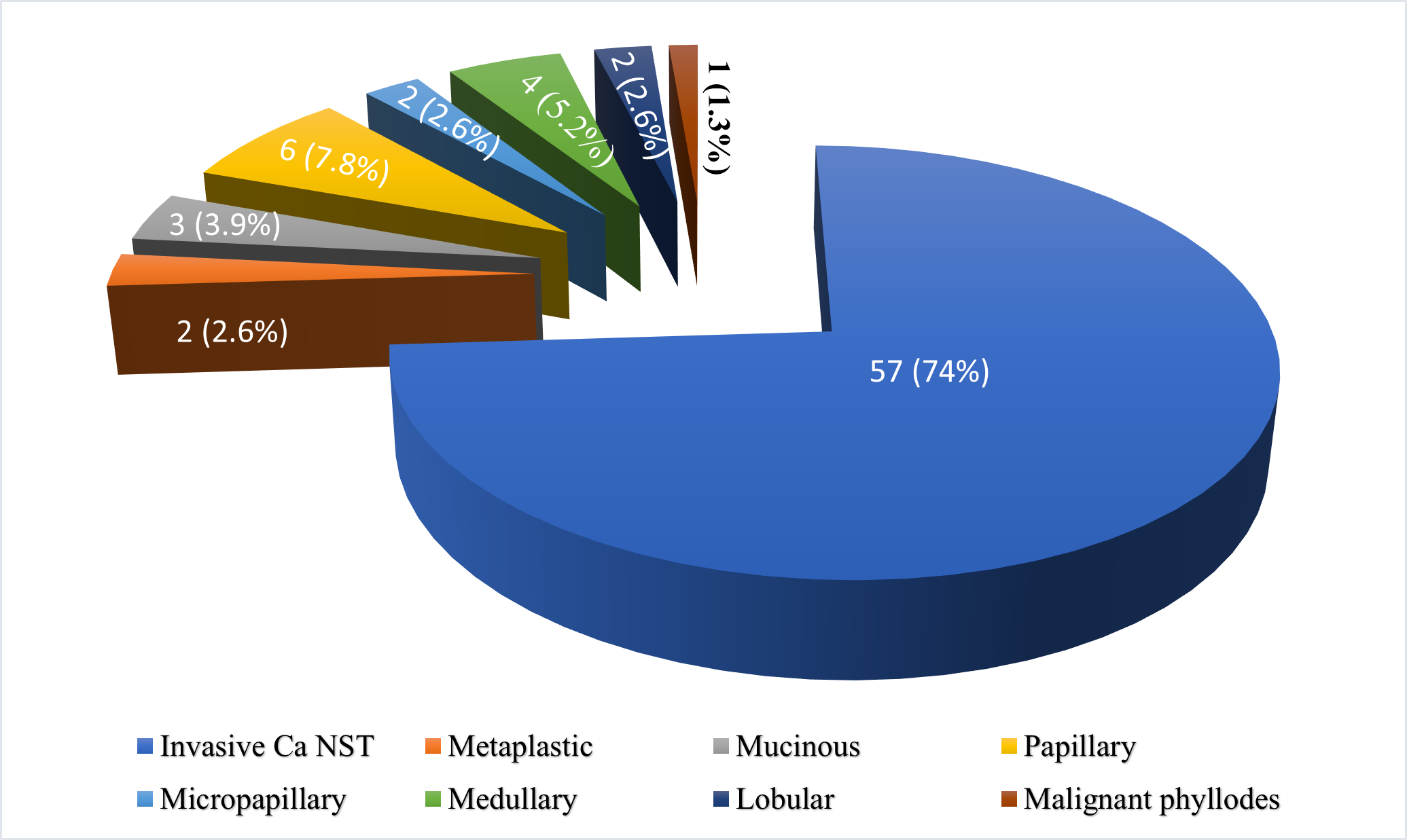

Benign breast lumps were diagnosed in 16 patients (17.2%). There were eight (8.6%) cases of fibroadenoma, four (4.3%) cases of fibrocystic change, two (2.2%) cases of lactating adenoma, a case each of tubular adenoma and atypical ductal hyperplasia. Seventy-seven patients (82.8%) had malignant breast lumps. Invasive carcinoma NST was the most common malignant lesion 57 (74.0%) observed in the study. Their distribution is shown in (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of the various malignant lesions based on histology.

Discussion

FNAC of the breast is commonly used as part of the diagnostic triad, which in addition includes clinical breast examination and radiological evaluation [2]. In our study, all the sixty cytologically-diagnosed malignant lesions were confirmed by histological analysis. On FNAC, 19 were benign with three (15.8%) of the cases of benign breast lump turning out to be malignant on histological diagnosis which represents a false negative result. We did not record any false positive results in this study. Similar result where all the cytologically proven neoplasms were confirmed by histology was seen in studies done by Al-Mayahee et al. [9] and Khan et al. [10]. Ogbuanya et al. [11] however, reported one case (2.5%) that was histologically diagnosed as benign out of 40 cases diagnosed malignant on cytology representing a false positive result. The 15.8% false negative result observed in this study is higher than the 3.5% [11], 4.2% [10] and 11.1% [9] reported in the previous studies. The high false negative result reported here is a cause for concern because of the clinical implication of increased probability to falsely miss cancers among breast aspirates by FNAC test. This could mislead a clinician and cause delay in treatment. Inadequate sampling during aspiration may have contributed to our high false negative results. Small tumour size in certain histological types (lobular carcinoma, mucinous, tubular, or medullary carcinoma) has also been implicated in false negative results [12]. The most attributed cause of false negative results reported in the literature is sampling error particularly in small tumours [13].

It is important to note that six cases each out of 93 were diagnosed as C3 (suspicious, probably benign) and C4 (suspicious for malignancy) on FNAC with all of them being malignant on histological examination (Table 2). This equivocal diagnostic result (C3 and C4) which comprised 12.9% of cases in this study is in concordance with reported literature values of 4-17.7% [10,11,14] indicating that these categories were not underused or overused in our study. It was suggested in some guidelines that cases classified in categories C3 and C4 should not exceed 20% of the total cases [15,16]. The low levels of insufficient specimens (C1) and suspicious diagnoses (C3 and C4) in this study are probably due to appropriate conditions in which FNAC was performed and reported, allowing an accurate diagnosis in most cases.

In this series, FNAC is more specific than sensitive for breast lumps with a maximum positive predictive value. The high predictive value of positive results allows for early diagnosis, and treatment of breast malignancies. These findings agree favourably with results from similar studies [7,9,14]. From the literature, the sensitivity ranges from 80% to 98% and the specificity may be up to 100% [17,18]. The diagnostic accuracy of the present study is 96.2%, conforming with previous findings of 94.5% by Al-Mayhee et al. [9] and 98.8% by Khattak et al. [19]. The strong correlation between FNAC and histology observed in this study is consistent with observations from other studies [10,20]. It has even been suggested that FNAC positive for breast cancer (C5) eliminates the need for open biopsy and allows the surgeon to proceed with mastectomy with confidence [21]. Given its reliability, high efficiency, convenience, and low cost, FNAC is a worthwhile diagnosis method, especially in hospitals like ours with limited resources.

FNAC has certain limitations such as inadequate samples and suspicious diagnoses as had been equally observed in this study. The overlapping of cytological features can cause cytodiagnostic errors and wrong diagnosis when the cytologic architecture mimics malignancy [10]. Also, in FNAC both false-negative and false-positive results can occur [7]. We observed three false negative cases, but there is the possibility that more may have been missed because of the retrospective nature of the study. Hence, a good practice is to resort to histological confirmation when significant concerns exist regarding false positive and negative diagnoses [11]. It has equally been recommended that cell block technique be employed in all cases along with FNAC to help in the accurate diagnosis of breast lesions [22]. Cell block has an added advantage that it may be used as an alternative to more invasive technique of breast biopsy and the sections of the cell block can be used for special stains and immunohistochemistry [22].

Most patients were between 41 and 50 years of age (35.5%) which is comparable to reports of previous breast cancer studies [7,9-11]. The difference of 10 years for the peak age incidence between benign and malignant breast lesions observed in our study agrees with findings in Southeast Nigeria by Ogbuanya et al. [11]. This emphasizes the sharp increase in the incidence rates of breast cancer with age [7]. The association between age and cytological findings of breast cancer was statistically significant in our study (p <0.001) as patients with a diagnosis of breast cancer were significantly older than those with benign diagnosis. The size of breast lumps among the former was also larger. The relationship between tumour size and cytological diagnosis was evaluated in the study and was observed to be statistically significant (p <0.001). All 65 patients (100%) who had a breast mass above 5 cm in this study were diagnosed with breast malignancy as opposed to 12 (42.9%) in those with masses between 2 and 5 cm. This implies that if the patient’s age and size of breast lumps are considered in combination with FNAC, the interpretation and the prediction for malignancy could even be improved considering their association with cytological findings of breast cancer on bivariate analysis in the present study. Patumanond et al. had earlier considered age together with size of breast lumps as potential predictors of breast cancer in their study [23].

In the present study, majority of lumps (43.0%) were situated in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Similar observations were equally reported in other studies [7,11,14,22,23]. This high proportion of upper outer quadrant involvement is most likely a reflection of the greater amount of breast tissue in this quadrant. The association between the location of the masses and cytological findings of breast cancer in our study was not significant (p= 0.175). However, a higher percentage of those with upper inner quadrant masses were malignant. In contrast, a significant association between the above was observed by Patumanond et al. (p <0.001) [23].

The most common malignant breast lesion reported in our study was invasive carcinoma NST, whereas the most common benign breast lesion was fibroadenoma, followed by fibrocystic change. These findings from our study are largely consistent with results from other studies [7,22,24].

Limitations of the Study

The main drawback of this study is its retrospective nature. A prospective study, preferably in combination with cell block would throw more light on this comparison.

Conclusion

Fine needle aspiration cytology is an easy, safe and a very useful diagnostic aid in the evaluation of suspicious breast lesions especially in resource-limited settings. Its accuracy can still be improved when used in combination with the patient’s age and size of the breast lumps as its association with these factors was significant in this study.

We observed some concerns with FNAC such as the three false negative results, suspicious lesions (C3 and C4) on FNAC which were later diagnosed as malignant on tissue histology, absence of important information about the pathological types and intrinsic behaviours of the tumours. Cell block could be a valuable addition to improve on its diagnostic accuracy in this regard when fully established in our centre. Until then, it will continue to fulfil complementary needs with tissue histology in our setting.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

We received no funding for the writing of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr William Akerele, Dr Cyril Obasuyi, Dr Blessing Tagar, and Mr Elliot Ubani for their contribution to this review.

Ethical Approval

The protocol for the study was approved by the Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital Research and Ethics committee with reference no: ISTH/HREC/20230810/500. The ethical principles of confidentiality were applied throughout the period of the study.

References

2. Ahmed I, Nazir R, Chaudhary MY, Kundi S. Triple assessment of breast lump. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007 Sep;17(9):535-8.

3. Shaaban AM, Sharma N. Management of B3 lesions—practical issues. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 2019; 11:83-88.

4. Kocjan G, Bourgain C, Fassina A, Hagmar B, Herbert A, Kapila K, et al. The role of breast FNAC in diagnosis and clinical management: a survey of current practice. Cytopathology. 2008 Oct;19(5):271-8.

5. Garbar C, Cure H. Fine needle aspiration cytology can play a role in operable breast cancer. ISRN Oncol. 2013;2013:935796.

6. Daramola AO, Odubanjo MO, Obiajulu FJ, Ikeri NZ, Banjo AA. Correlation between Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology and Histology for Palpable Breast Masses in a Nigerian Tertiary Health Institution. Int J Breast Cancer. 2015;2015:742573.

7. Bharatkumar PH, Samanta M, Nikhra P, Behl V, Ashvinbhai PU. Comparison of cytological and histopathological findings in breast lesions- a tertiary care center. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2023;16:119-23.

8. Field AS, Schmitt F, Vielh P. IAC Standardized Reporting of Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Cytology. Acta Cytol. 2017;61(1):3-6.

9. Al-Mayahee TM, Al-Rikabi MH. Accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology in comparison with histopathology in the diagnosis of breast lesion2016-2017. Thi-qua Med J. 2017;13:135-46.

10. Khan A, Jamali R, Jan M, Tasneem M. Correlation of fine needle aspiration cytology and histopathology diagnosis in the evaluation of breast lumps. Int J Med Stud. 2014;2:40-3.

11. Ogbuanya AU, C Anyanwu SN, Nwigwe GC, Iyare FE. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology for palpable breast lumps in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2021 Jan;24(1):69-74.

12. Ibikunle DE, Omotayo JA, Ariyibi OO. Fine needle aspiration cytology of breast lumps with histopathologic correlation in Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria: a five-year review. Ghana Med J. 2017 Mar;51(1):1-5.

13. Saad RS, Silverman JF. Breast. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur D, editors. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 3rd edition. Philadephia, PA, USA: Elsevier Saunders; 2008. pp. 713-72.

14. Chetan KB, Sreenivas N. Comparative study between fine needle aspiration cytology and histopathology in the diagnosis of breast lump. IP J Diagn Pathol Oncol. 2018;3:60-67.

15. Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Törnberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition--summary document. Ann Oncol. 2008 Apr;19(4):614-22.

16. Mitra S, Dey P. Grey zone lesions of breast: Potential areas of error in cytology. J Cytol. 2015 Jul-Sep;32(3):145-52.

17. Wilkinson EJ, Bland KI. Techniques and results of aspiration cytology for diagnosis of benign and malignant diseases of the breast. Surg Clin North Am. 1990 Aug;70(4):801-13.

18. Gukas ID, Nwana EJ, Ihezue CH, Momoh JT, Obekpa PO. Tru-cut biopsy of palpable breast lesions: a practical option for pre-operative diagnosis in developing countries. Cent Afr J Med. 2000 May;46(5):127-30.

19. Khattak MS, Ahmad F; Khalil Ur Rehman. Role Of Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology In Diagnosis Of Palpable Breast Lesions And Their Comparison With Histopathology. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2020 Jan-Mar;32(1):83-86.

20. Rupom TU, Choudhury T, Banu SG. Study of fine needle aspiration cytology of breast lump: Correlation of cytologically malignant cases with their histological findings. BSMMU J. 2011;4(2):60-4.

21. Wanebo HJ, Feldman PS, Wilhelm MC, Covell JL, Binns RL. Fine needle aspiration cytology in lieu of open biopsy in management of primary breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1984 May;199(5):569-79.

22. Kawatra S, Sudhamani S, Kumar SH, Roplekar P. Cell block versus fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of breast lesions. J Sci Soc 2020; 47: 23-7.

23. Patumanond J, Kayee T, Sukkasem U. Empirical accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for preoperative diagnoses of malignant breast lumps in hospitals with restricted health resources. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(3):295-9.

24. Mukharji S, Pandit A, Sudhamani S. A Comparative study to determine the efficacy of FNAC and histopathology in breast lesions. J Adv Med Dent Scie Res2019; 7: 81-85.