Short Communication

Cross-sectional studies [1] and small case series [2] have suggested that increased left ventricular (LV) trabeculation may be a manifestation of benign athletic remodeling in predisposed individuals. Interestingly, there is some support that increased LV trabeculation may improve cardiac performance through increases in stroke volume, stroke work and cardiac index (preprint) [3]. The practical implications are that athletes are at risk of over diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC). Whilst this has been considered in international recommendations for sports participation that isolated incidentally discovered LV hyper-trabeculation should not be diagnosed as LVNC in the absence of symptoms, family history, ECG abnormalities or LV impairment [4], there is no gold standard criteria for the diagnosis of LVNC resulting in profound difficulty in case definition and subsequent variation in practice.

The diagnosis of LVNC is often suggested by cardiac imaging for which a cacophony of different findings, measurements and ratios have been proposed to distinguish between normality and LVNC but with neither convincing success nor demonstrable superiority of one method over others [5]. Selections and combinations of these “LVNC imaging criteria” have been used in research to highlight that some groups, including those with the potential for cardiac remodeling based on hemodynamic differences, possess a greater amount of increased LV trabeculation compared to healthy control populations. These groups include those with heart failure [6], sickle cell anemia [7], pregnant women [8] and athletes [1]. The scale of the problem in athletes varies between 1.4% [9] to 18.3% [1] depending on how conservatively or liberally increased LV trabeculation is defined, with general agreement that the proportion of athletes in whom there is real concern of LVNC, based on additional clinical features, is as low as 0.1% [9] to 0.9% [1].

The findings of cross-sectional studies require cautious interpretation considering the potential influences of confounding factors, selection bias and inability to discern that increased LV trabeculation follows the exposure of high exercise volume looking at a single time-point. For this reason, we conducted a study in novice marathon runners investigating whether a self-directed increase in exercise, by running training, could result in an increase in LV trabeculation and have reported the findings previously [10].

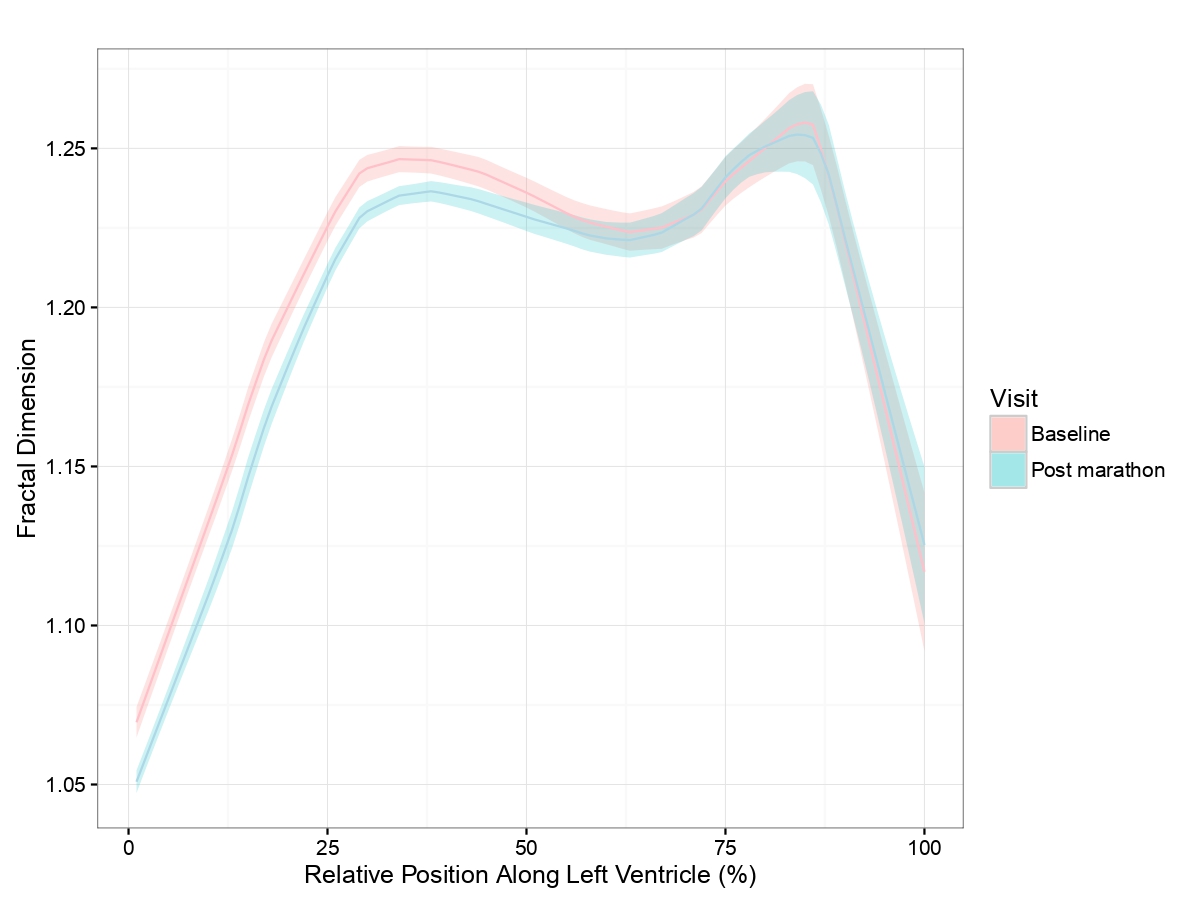

We recruited 120 first-time marathon runners aged 18-35 years, based on our understanding that older runners would have less myocardial plasticity for remodeling [11]. The final cohort comprised only 68 subjects due to attrition from injury and missed follow up appointments. Multiple measures of LV trabeculation using echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) were employed, finding no clinically important change in LV trabeculation after 17 weeks of training and completing a marathon. In addition, measures of LV trabeculation had poor agreement with each other, with echocardiographic Chin criteria [12] demonstrating a small increase in LV trabeculation and CMR-based Petersen criteria [13] demonstrating a small drop. Though both of these small changes were statistically significant, they resulted from sub-millimeter differences in layer thicknesses, which are impossible to measure on an individual level and therefore biologically unimportant. Other measures of LV trabeculation did not change, though the prevalence of apical trabeculation, particularly as determined by CMR fractal dimension measurement [14] was unexpectedly high in this study cohort at baseline. The mean fractal dimension also indicated that endocardial border complexity at the basal LV reduced after the marathon, compared to baseline measurements but beyond the mid-ventricular level, moving towards the apex, fractal dimensions did not change (Figure 1). Speculatively, this may be the result of other structural remodeling changes such as 3% increase in LV end-diastolic volume and 4% increase in compact myocardial LV mass, previously reported in this cohort [15].

Figure 1: Mean fractal dimension across the entire left ventricle from base (0%) to apex (100%). Baseline (pink) and post marathon (blue) results are displayed together with the respective shaded regions representing 95% confidence intervals of mean values.

Though we were unable to demonstrate a meaningful change in LV trabeculation in novice marathon runners, the situation in competitive athletes with substantially higher exercise volume and longer duration of participation at higher intensity, could be drastically different. As we have demonstrated previously, running a first marathon achieving a near average finishing time is not associated with an increase in peak oxygen consumption or cardiac remodeling changes akin to those seen in athletes. Unsurprisingly, a 17-week, unsupervised beginner’s training plan is a relatively weak stimulus for cardiac remodeling when considered on the spectrum of exercise-induced remodeling. Consequently, to better address the question of whether athletes develop exercise-induced LV trabeculation, one could study whether adolescent athletes joining academies develop excessive LV trabeculation over years of professional sport participation. The advantages of studying such a group would be that weekly training times would be expected to increase to elite athlete levels and professional athletes may be reassessed on an annual/biennial basis ifparticipating in a regular cardiovascular screening program. Pre-participation screening and surveillance of adolescent athletes for ongoing eligibility has reached its 20th year in the English Football Association cardiac screening program [16] and echocardiograms could be examined retrospectively for LV trabeculation. Examining, with accuracy, whether LV trabeculation increases over time in an athlete’s career and whether LV trabeculation regresses with detraining from injury or retirement, could yield important discoveries in exercise-induced LV trabeculation and confirm or refute its existence. By including an age-matched control group, natural changes in LV trabeculation over decades can be compared, as studies demonstrate that LV trabeculation decreases with normal ageing [17,18].

Our study also highlighted a greater reproducibility of trabeculation quantification through measurements conducted by CMR as compared to echocardiography. A key obstacle to accurately quantifying LV trabeculation and detecting small changes over multiple assessment time points is the subjectivity of manual measurements and oversimplification of a 3-dimensional global LV property into a regionally representative ratio of linear measurements. Hence, reliable automated techniques quantifying global and regional trabeculation across the whole LV would represent an important and much needed breakthrough in this area.Such technology could be applied to a large Biobank of healthy individuals to better understand the limits of normal LV trabeculation and address the problem that current proposed thresholds are oversensitive, capturing far more than simply the LVNC population of interest.

In conclusion, it remains unclear whether LV trabeculation can be exercise-induced and is potentially a manifestation of the normal athletic heart. We were unable to demonstrate an increase in LV trabeculation in a cohort of young, unsupervised, novice marathon runners but such a modest change in physical activity for a relatively short period of time may indicate that the exercise stimulus employed was insufficient in our study. The current evidence from cross-sectional studies and small case series is not conclusive and future studies should employ highly reproducible, automated techniques of LV trabeculation quantification in longitudinal studies spanning the adolescent to adult competitive athlete career to better address the question. Until such time, caution should be applied before diagnosing LVNC in an athlete on the basis of imaging findings alone.

References

2. D'Ascenzi F, Pelliccia A, Natali BM, Bonifazi M, Mondillo S. Exercise-induced left-ventricular hypertrabeculation in athlete's heart. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015 Feb 15;181:320-2.

3. Meyer HV, Dawes TJ, Serrani M, Bai W, Tokarczuk P, Cai J, et al. Genomic analysis reveals a functional role for myocardial trabeculae in adults. BioRxiv. 2019 Jan 1:553651.

4. Pelliccia A, Solberg EE, Papadakis M, Adami PE, Biffi A, Caselli S, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive and leisure time sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, and pericarditis: position statement of the Sport Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). European Heart Journal. 2019 Jan 1;40(1):19-33.

5. Abela M, D’Silva A. Left ventricular trabeculations in athletes: epiphenomenon or phenotype of disease?. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2018 Dec 1;20(12):100.

6. Kohli SK, Pantazis AA, Shah JS, Adeyemi B, Jackson G, McKenna WJ, et al. Diagnosis of left-ventricular non-compaction in patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction: time for a reappraisal of diagnostic criteria?. European Heart Journal. 2008 Jan 1;29(1):89-95.

7. Gati S, Papadakis M, Van Niekerk N, Reed M, Yeghen T, Sharma S. Increased left ventricular trabeculation in individuals with sickle cell anaemia: physiology or pathology?. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013 Sep 30;168(2):1658-60.

8. Gati S, Papadakis M, Papamichael ND, Zaidi A, Sheikh N, Reed M, et al. Reversible de novo left ventricular trabeculations in pregnant women: implications for the diagnosis of left ventricular noncompaction in low-risk populations. Circulation. 2014 Aug 5;130(6):475-83.

9. Caselli S, Ferreira D, Kanawati E, Di Paolo F, Pisicchio C, Jost CA, Spataro A, Jenni R, Pelliccia A. Prominent left ventricular trabeculations in competitive athletes: A proposal for risk stratification and management. International journal of cardiology. 2016 Nov 15;223:590-5.

10. D'Silva A, Captur G, Bhuva AN, Jones S, Bastiaenen R, Abdel-Gadir A, et al. Recreational marathon running does not cause exercise-induced left ventricular hypertrabeculation. International Journal of Cardiology. 2020 Apr 29.

11. Ogawa T, Spina RJ, Martin 3rd WH, Kohrt WM, Schechtman KB, Holloszy JO, et al. Effects of aging, sex, and physical training on cardiovascular responses to exercise. Circulation. 1992 Aug;86(2):494-503.

12. Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, Jue K, Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990 Aug;82(2):507-13.

13. Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, Robson MD, Francis JM, Anderson RH, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005 Jul 5;46(1):101-5.

14. Captur G, Muthurangu V, Cook C, Flett AS, Wilson R, Barison A, et al. Quantification of left ventricular trabeculae using fractal analysis. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2013 Dec 1;15(1):36.

15. D’Silva A, Bhuva AN, Van Zalen J, Bastiaenen R, Abdel-Gadir A, Jones S, et al. Cardiovascular remodeling experienced by real-world, unsupervised, young novice marathon runners. Frontiers in Physiology. 2020 Mar 18;11:232.

16. Aengevaeren VL, Aengevaeren WR, Eijsvogels TM. Outcomes of Cardiac Screening in Adolescent Soccer Players. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2018 Nov;379(21):2083.

17. Dawson DK, Maceira AM, Raj VJ, Graham C, Pennell DJ, Kilner PJ. Regional thicknesses and thickening of compacted and trabeculated myocardial layers of the normal left ventricle studied by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2011 Mar;4(2):139-46.

18. Bentatou Z, Finas M, Habert P, Kober F, Guye M, Bricq S, et al. Distribution of left ventricular trabeculation across age and gender in 140 healthy Caucasian subjects on MR imaging. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging. 2018 Nov 1;99(11):689-98.