Abstract

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a comprehensive care protocol that incorporates evidence-based practices to achieve the most optimal postoperative outcomes, safe on-time discharge, and surgical cost efficiency. ERAS protocols have been adapted for specialty-specific needs and implemented by a variety of surgical disciplines including thoracic surgery. This mini-review provides an overview of recently reported results of Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery (ERATS) with emphasis on the impact of an ERATS protocol on postoperative complications, hospital length of stay, patient-report pain outcomes, opioid utilization, and costs.

Keywords

Thoracic surgery, ENHANCED recovery after thoracic surgery, Postoperative analgesia, Intercostal nerve block, Liposomal bupivacaine

Abbreviations

ERATS: Enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery; MME: Morphine milligram equivalent; R-VATS: Robotic Video assisted thoracic surgery; VATS: Video assisted thoracic surgery; LOS: Length of stay

Care for Thoracic Surgical Patients

The majority of lung resections are performed for treatment of lung cancer. Thoracic patients are generally older with multiple co-morbidities, notable for coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes and obesity [1]. Up to 80% of patients undergoing thoracic surgical procedures have a history (former or current) of cigarette smoking [1]. Surgical approaches are generally open thoracotomy or minimally invasive thoracoscopy. Thoracotomy, either with splitting or sparing of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles, requires the division of intercostal muscles and the separation of ribs with heavy metal retractors. Thoracotomies are considered the most painful incisions with a high incidence of chronic postoperative pain and persistent opioid utilization [2,3]. Minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery (MITS) uses specialized instruments and a video-endoscope for intra-thoracic operations. The addition of robotic technology increases the sophistication and capability of surgical thoracoscopies by reducing tremors and providing enhanced high-definition visualization. It is well demonstrated that pulmonary lobectomy for lung cancer by thoracoscopic surgery is associated with less postoperative pain, fewer complications, shorter length of stay and more cost-efficiency than those performed by open thoracotomy [4-6]. The intensity and duration of acute postoperative pain following thoracic surgical procedures is a major source of anxiety for patients and contributes to postoperative complications. Inadequately controlled postoperative pain leads to less mobilization from bed to chair, decreased ambulation as well as ineffective chest physiotherapy and cough responses. Such physical limitations coupled with the acute decrease of lung function following lung resection, particularly in those with pre-existing reduced pulmonary reserve due to smoking-induced emphysema, have significantly increased the risk of respiratory complications. Therefore, adequate pain control is an essential component of a postoperative care protocol for thoracic surgical patients. A pain regimen that relies heavily on potent opiate medication can be hampered by side effects including respiratory depression, drowsiness, delayed return of bowel and bladder function, and nausea/emesis. These side effects contribute to increased risk for atelectasis/hypoxemia, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, prolongation of hospitalization and reduced patient satisfaction. Table 1 summarizes factors that can adversely affect postoperative outcomes and timely discharge. Strategies such as pharmacologic prophylaxis to reduce post-operative atrial fibrillation and deep vein thrombosis as well as measures to minimize pulmonary, gastro-intestinal and genito-urinary complications have been developed and practiced [7]. Examples of efforts that aim to mitigate postoperative pain include implementation of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), paravertebral and intercostal nerve blocks, thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA), modified thoracotomy closure techniques, and a transition from open thoracotomy to MITS [8,9]. Thoracic epidural analgesia, while effective for post-thoracotomy pain, is not without risk and adverse side effects [10]. Successful epidural catheter placement is operator-dependent and management of which is completely contingent on anesthesia consultants. Many thoracic postoperative care protocols, referred to as “enhanced recovery” care pathway, were implemented to address these issues to optimize postoperative recovery and to facilitate safe discharge with measurable results in the 1980s and 1990s [11,12]. These marked the beginning of “enhanced recovery” efforts in thoracic surgery. A recent systematic review of the influence of enhanced recovery pathways in elective lung surgery, however, identified a significant knowledge gap and highlighted the need for well-designed trials to provide conclusive evidence of the role of such care pathway for thoracic surgical patients [13].

|

Patient factors |

Underlying co-morbidities: obesity, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, renal dysfunction, current/past history of cigarette smoking. |

|

Procedural factors |

Thoracotomy versus minimally invasive thoracoscopy Effective pain management Cardiac: atrial fibrillation Pulmonary: persistent air-leak, atelectasis, hypoxemia, pneumonia, chest drain management GU: urinary retention GI: delayed return of bowel function |

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)

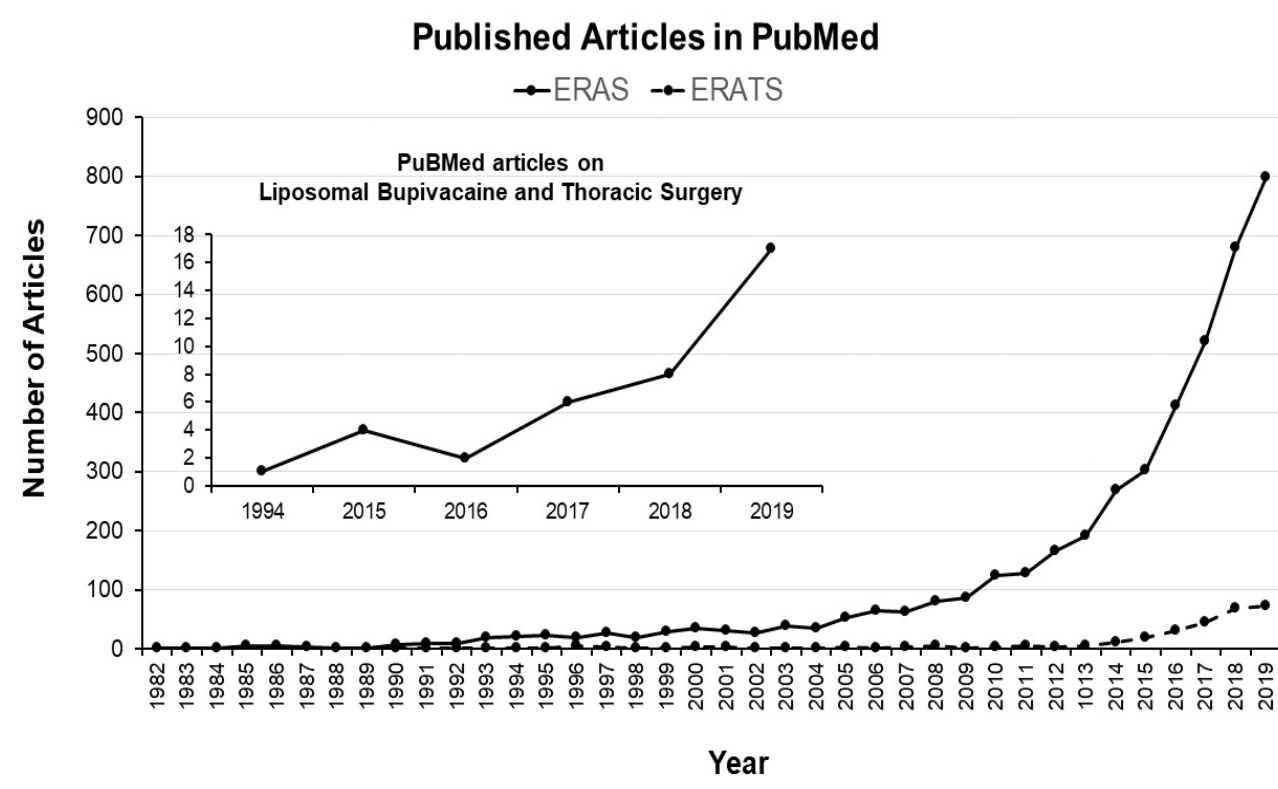

The ERAS concept, developed in early 2000’s by clinicians in Europe as a care protocol to address pre-, peri- and post-operative components of surgical patients with an overarching goal of achieving optimal postoperative outcomes, safe discharge while being cost-effective [14]. The principle of ERAS is the multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach to resolve issues that cause complications in order to accomplish quality post-operative recovery. This aim is achieved by systemically applying evidence-based practice, formatted into a care protocol with built-in frequent updates to optimize quality improvements. One important feature of ERAS is a built-in internal auditing process to ensure compliance and achievement of desired patient outcomes following implementation. ERAS has gained traction globally and is utilized by many surgical specialties including general thoracic surgery, which is exemplified by the exponential increase in the number of publications listed in PubMed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The number of publications cited in PubMed when searched for using “ERAS” and “ERAS and thoracic surgery”. There is an exponential increase in the number of publications on the topic of ERAS (original articles, reviews, commentaries) within the last 10 years while ERATS publications have started increasing only in the last 5 years.

Enhanced Recovery After Thoracic Surgery (ERATS)

The principles of ERAS are maintained by developing and implementing this care pathway for thoracic patients. The ERAS® society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgery published guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery with recommendations for 45 items that cover pre-admission, admission, intraoperative care, and postoperative care [7,14]. Table 2 summarizes the ERATS protocol developed and implemented at our institution. This is very similar to those described by other groups [15-19]. ERATS aims to standardize and streamline all aspects of care for thoracic patients in order to achieve the following metrics: optimal pain control, lower postoperative complications, on-time discharge (i.e., shortest possible hospital stay), decreased opioid utilization, and cost-effectiveness. It is well described that all components of ERATS synergistically contribute to the desired satisfactory outcomes; however, adequate pain control is most pertinent to thoracic surgical patients. In our opinion, innovation in the use of a long-acting preparation of local anesthetic agent such as liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel®, Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Parsippany, NJ) for direct intercostal nerve blocks, as advocated by Mehran and colleagues within the context of ERATS, which also focuses on non-opioid multimodal analgesics, has changed the practice of post-thoracotomy and post-thoracoscopy pain control. The management of acute postoperative pain is streamlined by elimination of patient-controlled thoracic epidural analgesia or intravenous opioids. This allows the surgical team total “real-time” assessment of patient pain levels with the ability to intervene and administer appropriate measures for pain control. The overall reduction of postoperative opioid use following ERATS implementation, as reviewed below, has been observed by many independent investigators. Minimizing post-discharge narcotic dispensing reduces opiate availability to the public and contributes to the fight against the opioid abuse epidemic in the USA and other parts of the world. Chronic post-thoracotomy pain has been reported to be around 40% at one year after surgery [2]. Intense early acute postoperative pain has been identified as a strong predictor of long-term post-thoracotomy pain [20]. The incidence of persistent opioid use (filling of at least one additional opioid prescription 90 to 180 days after surgery) in elderly patients (>65 years old) undergoing lung resection was approximately 31% (as high as 17% in opioid-naïve individuals) in a recent review of the SEER-Medicare database from 2008 to 2013 [21]. Similar findings were also reported by Lee et al. and Brescia et al. [22,23]. In addition to the well-known side-effects of opioid use such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, ileus, suppression of respiratory drive, and drowsiness/sedation, an association between persistent opioid use and worse overall survival after lobectomy for stage 1 lung cancer has recently been reported [24].

|

Preoperative phase: surgeon and anesthesia team |

Preoperative evaluation and management of modifiable co-morbidities Counseling and set realistic expectations of postoperative recovery, reading materials Carbohydrate drinks |

|

Perioperative phase: surgeons and anesthesia team |

Oral analgesics Antibiotic wound prophylaxis Mechanical/pharmacological DVT prophylaxis Anesthesia cares: euvolemia, postoperative nausea/vomiting prophylaxis, avoid hypothermia, minimize volatile inhalational anesthetics Intraoperative surgical wound infiltration and posterior intercostal nerve block with liposomal bupivacaine |

|

Postoperative phase: surgeons and APRN / nursing team |

Multimodal non-opioid analgesics: acetaminophen, NSAIDS (ibuprofen or ketorolac), gabapentin, tramadol and PRN schedule II opioids (morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone), minimize or avoid the use of thoracic epidural analgesia Out of bed/ambulation POD0 Regular diet Removal of bladder catheter POD1/2 Remove chest drain once air leak stops and serosanguinous drainage volume <5 ml/kg/day Urinary retention prophylaxis for men >50 years old: tamulosin 0.4 mg po starting POD0 Atrial fibrillation prophylaxis: continue perioperative betablocker otherwise start metoprolol 12.5 mg twice a day POD0 for anatomic lung resection Intravenous fluid balanced salt solution 1 ml/kg/hr until void after bladder catheter removal DVT prophylaxis: heparin SQ 5000 units q8hrs and intermittent pneumanic compression GI prophylaxis: proton pump inhibitor, laxatives |

|

Discharge planning: surgeons and APRN |

Verbal and printed discharge instructions Personalized discharge opioid prescription (tramadol and oxycodone or hydromorphone) Multimodal non-opioid analgesics: acetaminophen, NSAIDS (ibuprofen or ketorolac), gabapentin |

|

PRN: pro re nata / as needed; POD: postoperative day; SQ: subcutaneous; APRN: advanced practice registered nurse; DVT: dep vein thrombosis; GI: gastro-intestinal; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

|

Review of recent ERATS publications in the following paragraphs focuses on the impact of enhanced recovery protocol on the following metrics: pain, opioid use, complications, hospital LOS and costs. The authors outline essential components of their enhanced recovery protocols, which adhere to the principles of ERAS and share similar measurable objective outcome metrics. Results of these reports are summarized in Table 3.

|

Publications |

n (Pre-ERATS vs ERATS) |

Hospital LOS |

Complications |

Pain levels |

MME In-hospital opioid use |

MME Post-discharge opioid use |

Re-admission |

Cost |

|

Van Haren |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

1109 / 213 |

decrease |

decrease |

not report |

not report |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

Thoracoscopy |

506 / 129 |

decrease |

No change |

not report |

not report |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

Rice |

propensity matched |

|||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

73 / 73 |

decrease |

decrease |

decrease |

decrease |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

Thoracoscopy |

50 / 50 |

decrease |

decrease |

No change |

decrease |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

Martin (2015-2017) |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

62 / 58 |

decrease |

No change |

No change |

decrease |

not report |

no change |

decrease |

|

Thoracoscopy |

162 / 81 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

decrease |

not report |

no change |

decrease |

|

Haro (2015-2019) |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy/ |

169/126 |

decrease |

decrease |

Not report |

decrease |

not report |

no change |

decrease |

|

Razi (2017-2019) |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

30 / 32 |

No change |

No change |

decrease |

decrease |

decrease |

no change |

not report |

|

Thoracoscopy |

126 /184 |

No change |

No change |

decrease |

decrease |

decrease |

no change |

not report |

|

Madani (2011-2013) |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

127 / 107 |

decrease |

decrease |

not report |

not report |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

Paci (2011-2013) |

||||||||

|

Thoracotomy |

58 / 75 |

decrease |

decrease |

not report |

not report |

not report |

no change |

decrease |

|

Brunelli (2014-2017) |

||||||||

|

Thoracoscopy |

365 / 235 |

No change |

No change |

not report |

not report |

not report |

no change |

not report |

|

MME: milligram of morphine equivalent; LOS: length of stay |

||||||||

Razi and colleagues at the University of Miami reported the impact of ERATS for patients undergoing lung resections either by robotic video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (R-VATS) (pre-ERATS: 126, ERATS: 184) or by open thoracotomy (pre-ERATS 30, ERATS: 32) in a retrospective study using comparable cohorts of pre-ERATS patients as historical controls at the University of Miami Health System (1/1/2017 to 1/31/2019) [25]. Thoracic epidural analgesia was not used in thoracotomy patients. All patients received intraoperative posterior intercostal nerve blocks and infiltration of surgical wounds with liposomal bupivacaine. In robotic VATS patients, there was significant reduction of patient-reported pain, reduction of in-hospital and post-discharge opioid utilization and no difference in postoperative morbidity or hospital LOS following ERATS implementation. In thoracotomy patients, ERATS was associated with a significant decrease of patient-reported pain with no increase in opioid requirement, even in the absence of thoracic epidural analgesia which was coupled with a profound reduction of post-discharge opioids prescribed; this attested to the effectiveness of a multimodal opioid-sparing analgesics strategy. Similar postoperative complication rates between the two cohorts and a median one-day reduction of LOS in ERATS patients (not reaching statistically significance with p=0.1) were observed.

Martin and associates from the University of Virginia Health System (Charlottesville, Virginia) reported their early experience of implementing ERATS for patients undergoing lung resection by video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) (pre-ERATS: 162, ERATS-VATS: 81) or by thoracotomy (pre-ERATS: 62, ERATS-T: 58) in a retrospective study using comparable cohort of patients as historical controls (1/1/2015 to 5/1/2017) [16]. The authors described a dynamic process of the protocol implementation with many adjustments based on team member inputs, feedback from patients and real-time evaluation of results. Liposomal bupivacaine intercostal nerve blocks were used on every patient with an additional single subarachnoid injection of preservative-free morphine for thoracotomy and VATS anatomic lung resection. There was significant reduction of in-hospital opioid use with no difference in patient-reported pain, short-term postoperative complications, and hospital LOS in VATS patients. In thoracotomy patients, ERATS was associated with reduction of in-hospital opioid use and shorter LOS, but no difference in pain levels. Most importantly, there was significant reduction of total hospital costs in both VATS and thoracotomy patients following ERATS implementation. In a follow-up study, Martin et al. performed a comparative analysis of clinical outcomes of patients undergoing lobectomy for lung cancer either by VATS or by thoracotomy in the setting of a comprehensive ERATS protocol [26]. They observed no difference in postoperative complications, in-hospital opioid use or hospital LOS between VATS and thoracotomy cohorts. VATS lobectomy was associated with lowered re-admission rate, less blood transfusion and fewer instances of pneumonia. They concluded that surgical incision may have less of an impact on outcomes in the setting of a comprehensive ERATS protocol.

Van Haren and colleagues from MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) performed a large retrospective review of the impacts of ERATS on 2886 pulmonary resections (pre-ERATS: 1615, transition: 929 and ERATS: 342) over a 10-year period (1/1/2006 to 12/31/2016) [15]. The demographics and operative details were comparable in the three cohorts. ERATS (transition period during which the protocol was being implemented and established protocol period) was associated with a significant decrease of thoracic epidural use and hospital LOS in both VATS and thoracotomy patients and reduction of cardiac and pulmonary complications in thoracotomy but not in VATS patients. A follow-up study from the same institution noted ERATS was associated with a facilitated delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy, with fewer delays from resection to treatment and higher rate of receiving 4 or more cycles, likely secondary to decreased morbidity with ERATS pathways [27]. Rice and colleagues, from the same institution, recently performed a matched-pairs comparison of an enhanced recovery pathway versus conventional management on opioid exposure and pain control in patients undergoing lung surgery by either VATS or open thoracotomy [28]. They 1:1 matched 125 ERATS patients using a cohort of 907 historical controls to form 123 pairs for comparative analysis. No thoracic epidural was used in ERATS patients and all had intercostal nerve block with liposomal bupivacaine compared to 66% and 16% in controls, respectively. There was a significant reduction of pulmonary complications and hospital LOS but not in-hospital mortality, 30- and 90-day morbidity following ERATS implementation. ERATS was associated with a drastic reduction of in-hospital MME and with more patients using tramadol (a schedule IV opioid with low potential for future dependency) both in-hospital and at discharge. There was a small but statistically significant reduction of patient-reported pain levels in the whole group and in thoracotomy subgroup but not in the VATS subgroup (p=0.09).

Madani, Paci and colleagues from McGill University (Montreal, Canada) reported the impacts of the thoracic enhanced recovery pathway on clinical outcomes and costs of lung resections by either VATS or thoracotomy [17,29]. Their first study involved 234 patients (pre-ERATS: 127 and ERATS: 107) undergoing pulmonary lobectomy by thoracotomy between 8/2011 and 10/2013. The demographics and operative characteristics were similar between the two cohorts. There was a significant reduction of hospital LOS and overall complications. Earlier ambulation, bladder catheter removal, chest tube removal, resumption of solid diet and discontinuation of intravenous fluid were observed in the ERATS cohort. Neither opioid use nor patient-reported pain scores were reported. In a subsequent study involving patients undergoing anatomic and non-anatomic lung resection by either VATS or thoracotomy, the authors from the same institution evaluated the impact of ERATS on perioperative outcomes and costs (institutional, health care system and society) before and after implementation of their enhanced recovery protocol. In addition to shorter hospital LOS and reduced postoperative complications, ERATS was associated with a mean reduction of costs at the institutional (CAN$2,600), healthcare system (CAN$2,850), and societal (CAN$4,400) levels; only the societal cost reduction was statistically significant.

Haro and colleagues from the University of California at San Francisco (San Francisco, CA) reported the clinical results of their ERATS program [18]. In a prospective before/after cohort study involving 295 patients (pre-ERATS: 169; ERATS:126) over a 3 year period from 10/2015 to 3/2019, ERATS implementation was associated with an increase in the use of thoracoscopic technique, reduction of intensive care unit admission, earlier removal of chest tubes and bladder catheter, lower hospital LOS, less postoperative complications and decreased total hospital costs.

Brunelli and colleagues from St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK reported the effect of ERATS on patients undergoing VATS anatomic lung resection from 4/2014 to 1/2017 with regards to hospital LOS, cardiopulmonary complications, mortality and re-admissions [19]. The study consisted of 600 patients (pre-ERATS: 365 and ERATS: 235) with the two cohorts having comparable demographics and operative characteristics. There was no difference in LOS, complications, mortality and re-admission after ERATS implementation. There was no report of opioid use and pain scores in this study. There was no mention of opioid-sparing analgesia strategy. The findings are not unexpected as recent reports, as discussed above, indicate that ERATS is not as impactful for patients undergoing VATS as compared to thoracotomy patients in reducing perioperative complications, LOS, re-admission and operative mortality. Modern-day VATS lung resections are associated with lower perioperative pain as well as morbidity and mortality [4, 5]. The use of minimally invasive thoracic surgery is considered a component of an ERATS program [7].

The benefits of ERAS are more than a simple reduction in hospital length of stay and rates or types of postoperative complications. It is very clear that ERATS consistently has a strong impact in the reduction of hospital LOS and postoperative complications, particularly for cardiopulmonary adverse events, in patients who undergo thoracotomy as opposed to a thoracoscopy [15-17]. When other outcome metrics such as subjective pain levels and opioid utilization are considered, the salutary effects of ERATS become apparent not only in thoracotomy patients but also in thoracoscopy patients [16,25,28]. Furthermore, the slight differences in outcomes described above may be attributed to ERATS protocols that were not uniform in protocols, were in different stages of implementation and have differing components.

Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Clinical experience with ERATS has been steadily increasing in the last 5 to 8 years. These independent publications from many centers contribute to filling of the knowledge gap and attest to the positive impact of well-developed and well-implemented protocols to improve the care and outcomes for thoracic surgical patients. It is very inspiring to observe a significant reduction of acute postoperative pain using opioid-sparing analgesic strategy and regional anesthesia with liposomal bupivacaine intercostal nerve blocks. The long term impact of effective early postoperative pain control on reducing the incidence of chronic pain and persistent opioid use following thoracic procedures remains to be seen and is an active focus of ongoing research [30]. It is even more encouraging to observe a drastic decrease in opioid utilization both in-hospital and post-discharge for ERATS patients. A decreased use of thoracotomy, fewer postoperative complications, and shorter hospital LOS should all contribute to a more efficient use of resources and lower hospital costs as outlined above. ERATS is a patient-centered care process driven and led by thoracic surgeons and anesthesiologists in collaboration with other providers. Consistent attention to detail, protocol updates, and periodic self-audits to maintain high-quality outcomes and compliance [31] all contribute to successful program implementation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest pertaining to the preparation of this manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the University of Miami for support in writing this manuscript. No sources of funding were provided.

Author Contributions

KK and BHN are responsible for writing (original draft). NRV is responsible for writing (review and editing). DMN is responsible for conceptualization, writing (original draft and review and editing), supervision and validation.

References

2. Bayman EO, Brennan TJ. Incidence and severity of chronic pain at 3 and 6 months after thoracotomy: meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain. 2014 Sep 1;15(9):887-97.

3. Kwon ST, Zhao L, Reddy RM, Chang AC, Orringer MB, Brummett CM, et al. Evaluation of acute and chronic pain outcomes after robotic, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, or open anatomic pulmonary resection. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017 Aug 1;154(2):652-9.

4. Bendixen M, Jørgensen OD, Kronborg C, Andersen C, Licht PB. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early stage lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2016 Jun 1;17(6):836-44.

5. Falcoz PE, Puyraveau M, Thomas PA, Decaluwe H, Hürtgen M, Petersen RH, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus open lobectomy for primary non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity-matched analysis of outcome from the European Society of Thoracic Surgeon database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg . 2016 Feb;49(2):602-609.

6. Nguyen DM, Sarkaria IS, Song C, Reddy RM, Villamizar N, Herrera LJ, et al. Clinical and economic comparative effectiveness of robotic-assisted, video-assisted thoracoscopic, and open lobectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Mar;12(3):296-306.

7. Batchelor TJ, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Brunelli A, Cerfolio RJ, Gonzalez M, et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2019 Jan 1;55(1):91-115.

8. Batchelor TJ, Ljungqvist O. A surgical perspective of ERAS guidelines in thoracic surgery. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2019 Feb 1;32(1):17-22.

9. Boisen ML, Schisler T, Kolarczyk L, Melnyk V, Rolleri N, Bottiger B, et al. The Year in Thoracic Anesthesia: Selected Highlights from 2019. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2020 Jul 1;34(7):1733-44.

10. Rice DC, Cata JP, Mena GE, Rodriguez-Restrepo A, Correa AM, Mehran RJ. Posterior intercostal nerve block with liposomal bupivacaine: an alternative to thoracic epidural analgesia. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2015 Jun 1;99(6):1953-60.

11. Wright CD, Wain JC, Grillo HC, Moncure AC, Macaluso SM, Mathisen DJ. Pulmonary lobectomy patient care pathway: a model to control cost and maintain quality. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1997 Aug 1;64(2):299-302.

12. Cerfolio RJ, Pickens A, Bass C, Katholi C. Fast-tracking pulmonary resections. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2001 Aug 1;122(2):318-24.

13. Fiore Jr JF, Bejjani J, Conrad K, Niculiseanu P, Landry T, Lee L, et al. Systematic review of the influence of enhanced recovery pathways in elective lung resection. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2016 Mar 1;151(3):708-15.

14. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA surgery. 2017 Mar 1;152(3):292-8.

15. Van Haren RM, Mehran RJ, Mena GE, Correa AM, Antonoff MB, Baker CM, et al. Enhanced recovery decreases pulmonary and cardiac complications after thoracotomy for lung cancer. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2018 Jul 1;106(1):272-9.

16. Martin LW, Sarosiek BM, Harrison MA, Hedrick T, Isbell JM, Krupnick AS, et al. Implementing a thoracic enhanced recovery program: lessons learned in the first year. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2018 Jun 1;105(6):1597-604.

17. Madani A, Fiore Jr JF, Wang Y, Bejjani J, Sivakumaran L, Mata J, et al. An enhanced recovery pathway reduces duration of stay and complications after open pulmonary lobectomy. Surgery. 2015 Oct 1;158(4):899-910.

18. Haro GJ, Sheu B, Marcus SG, Sarin A, Campbell L, Jablons DM, et al. Perioperative Lung Resection Outcomes After Implementation of a Multidisciplinary, Evidence-based Thoracic ERAS Program. Annals of Surgery. 2019 Dec 5.

19. Brunelli A, Thomas C, Dinesh P, Lumb A. Enhanced recovery pathway versus standard care in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017 Dec 1;154(6):2084-90.

20. Katz J, Jackson M, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 1996 Mar 1;12(1):50-5.

21. Nelson DB, Niu J, Mitchell KG, Sepesi B, Hofstetter WL, Antonoff MB, et al. Persistent opioid use among the elderly after lung resection: a SEER-Medicare study. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2020 Jan 1;109(1):194-202.

22. Lee JS, Hu HM, Edelman AL, Brummett CM, Englesbe MJ, Waljee JF, et al. New persistent opioid use among patients with cancer after curative-intent surgery. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Dec 20;35(36):4042.

23. Brescia AA, Harrington CA, Mazurek AA, Ward ST, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Factors associated with new persistent opioid usage after lung resection. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2019 Feb 1;107(2):363-8.

24. Nelson DB, Cata JP, Niu J, Mitchell KG, Vaporciyan AA, Antonoff MB, et al. Persistent opioid use is associated with worse survival after lobectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Pain. 2019 Oct 1;160(10):2365-73.

25. Razi SS, Stephens-McDonnough JA, Haq S, Fabbro II M, Sanchez AN, Epstein RH, et al. Significant reduction of postoperative pain and opioid analgesics requirement with an enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery protocol. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2020 Apr 3.

26. Krebs ED, Mehaffey JH, Sarosiek BM, Blank RS, Lau CL, Martin LW. Is less really more? Reexamining video-assisted thoracoscopic versus open lobectomy in the setting of an enhanced recovery protocol. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2020 Jan 1;159(1):284-94.

27. Nelson DB, Mehran RJ, Mitchell KG, Correa AM, Sepesi B, Antonoff MB, et al. Enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery is associated with improved adjuvant chemotherapy completion for non–small cell lung cancer. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2019 Jul 1;158(1):279-86.

28. Rice D, Rodriguez-Restrepo A, Mena G, Cata J, Thall P, Milton D, et al. Matched Pairs Comparison of an Enhanced Recovery Pathway Versus Conventional Management on Opioid Exposure and Pain Control in Patients Undergoing Lung Surgery. Annals of Surgery. 2020 Mar 30.

29. Paci P, Madani A, Lee L, Mata J, Mulder DS, Spicer J, et al. Economic impact of an enhanced recovery pathway for lung resection. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2017 Sep 1;104(3):950-7.

30. Brown LM, Kratz A, Verba S, Tancredi D, Clauw DJ, Palmieri T, et al. Pain and Opioid Use After Thoracic Surgery: Where We Are and Where We Need To Go. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2020 Mar 3; 109:1646-55.

31. Rogers LJ, Bleetman D, Messenger DE, Joshi NA, Wood L, Rasburn NJ, et al. The impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol compliance on morbidity from resection for primary lung cancer. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2018 Apr 1;155(4):1843-52.