Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell malignancies characterized by abnormal hematopoietic cell maturation, increased apoptosis of bone marrow cells, and anemia. The full complement of gene mutations that contribute to the phenotypes or clinical symptoms in MDS is not fully understood. Approximately 10%–25% of MDS patients harbor an interstitial heterozygous deletion on the long arm of chromosome 5, known as del(5q), creating

haploinsufficiency for a large set of genes. Two distinct commonly deleted regions (CDRs) in del(5q), proximal and distal CDR, have been identified. A number of genes in the regions have been implicated in essential for hematopoiesis and pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS through haploinsufficiency. In this paper, we first reviewed the genetics of del(5q) MDS and roles of important genes located in the CDRs that may contribute to abnormal hemopoiesis in patients. Given anemia is one of the significant clinical symptoms presented in MDS patients, thus, we also discussed the possible pathophysiologic causes and currenttreatments of anemia. The HSPA9 gene, encoding the protein mortalin, is located in the proximal CDR. HSPA9/mortalin is heat shock chaperone belonging to the heat shock protein 70 family. Our laboratory has been studying the role of HSPA9 gene in hematopoiesis and erythroid maturation for years. We not only reviewed the scientific findings of HSPA9 that we have been investigated, but also provide perspective in the field. This paper will be helpful for readers to better understand the genetics and pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS, as well as the role of HSPA9/mortalin in diseases.

Keywords

Erythroid maturation, Myelodysplastic syndrome, del(5q), HSPA9/mortalin, TP53/p53

Abbreviations

AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate; CDR: Commonly Deleted Region; CK1: Casein Kinase 1; EPO: Erythropoietin; ERK: Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; ESA: Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent; G-CSF: Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor; HSC: Hematopoietic Stem Cell; HSP: Heat Shock Protein; JAK2: Janus Kinase 2; MDS: Myelodysplastic Syndromes; NADH: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Hydrogen; OXPHOS: Oxidative Phosphorylation; RBC: Red Blood Cell; STAT5: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5; TCA: Tricarboxylic Acid

MDS and del(5q) MDS Genetics

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are acquired neoplastic myeloid proliferations in the bone marrow, where hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are impacted. MDS are characterized by clonal proliferation of HSCs, recurrent genetic abnormalities, progressive cytopenia, increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and myelodysplasia [1]. The symptoms of MDS patients normally include fatigue, shortness of breath, pallor, unusual bruising or bleeding, petechiae, anemia, and frequent infections [2,3]. The diagnosis of MDS require at least 10% of the cells in one hematopoietic lineage to be dysplastic, specifically, a megakaryocyte lineage needs to be at least 10% micromegakaryocytes or at least 40% dysmegakarypoiesis [4]. Treatment for MDS includes supportive care, drug therapy, and stem cell transplantation. Supportive care may include transfusion therapy, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), and antibiotic therapy. Drug therapy can slow the progression to AML which includes lenalidomide, immunosuppressive therapy, azacitidine and decitabine, and chemotherapy [5].

Approximately 10-15% of MDS cases acquire an interstitial deletion on chromosome 5q, known as del(5q) [6,7]. Del(5q) is among the most common cytogenetic aberrations in MDS and defines a unique MDS sub-category [8]. Two distinct commonly deleted regions (CDR), proximal and distal CDR, have been identified on the del(5q) region in MDS patients. The proximal CDR at 5q31.2-5q31.3 is associated with higher-risk MDS with higher rate of progression to AML. The distal CDR is a 1.5 Mb deletion encompassing 5q32–5q33.2 and present in the classical 5q- syndrome with better prognosis (Figure 1) [9-11]. The precise number of genes located in each CDR is not fully characterized. Some studies reported that the proximal CDR contains ~30 genes [12] and distal CDRs contains ~ 41 genes [13]. The analysis based on the copy number variations reveals ~ 405 genes on 5q including ~ 41 in proximal CDR and ~ 55 in distal CDR [11].

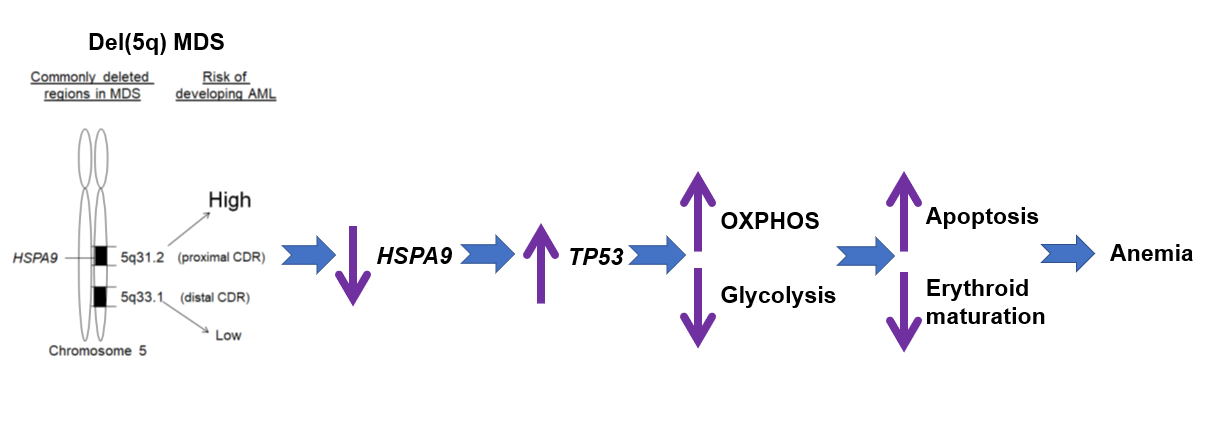

Figure 1: Genetic model of del(5q) and possible mechanisms of regulating anemia. Two CDRs, proximal and distal CDR, are presented in del(5q)MDS patients. The proximal CDR is associated with higher-risk MDS with higher rate of progression to AML. The distal CDR is present in 5q- syndrome with better prognosis. Haploinsufficiency of HSPA9 increases apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells and inhibits erythroid maturation,contributing to anemia seen in patients, which are probably regulated by TP53 and alterations in energy metabolism.

A number of genes in CDRs have been implicated in essential for hemopoiesis and pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS through haploinsufficiency (Table 1) [14]. For example, the RPS14 gene encodes for ribosomal protein S14, a structural protein of the 40S ribosomal subunit with important functions in ribosomal biogenesis [15]. Pellagatti et al. reported haploinsufficiency of the ribosomal gene RPS14 in HSCs in patients with the 5q− syndrome, and also indicated its implication in the etiology of congenital anemia like Diamond-Blackfan anemia [16]. Ebert et al. showed that suppressing RPS14 expression in normal cord blood CD34+ cells resulted in a marked lack of erythroid maturation, and that overexpression of RPS14 in del(5q) CD34+ cells restored it [17]. This groups also reported that haploinsufficiency for ribosomal protein genes including RSP14 causes selective activation of p53 in human erythroid progenitor cells [18]. The CSNK1A1 gene encodes casein kinase 1 alpha (CK1α), the smallest isoform of the CK1 kinase family. The heterozygous deletion of this gene in myeloid lineage results in red blood cell (RBC) proliferation and expansion in mice, indicating CSNK1A1 plays a central role in the biology of del(5q) MDS and is a promising therapeutic target [19]. Mutations in CSNK1A1 E98 have been reported in ~ 18% and D140 in ~ 7% del(5q) MDS patients, which are associated with poor prognosis and decreased life expectancy. Liu et al. reported that E98K and D140A mutants have reduced ability to promote phosphorylation of β-catenin, resulting in enhanced Wnt signaling. These mutations linked functional changes may promote expansion of abnormal myeloid progenitors in del(5q) MDS [20]. Genes with important functions in hematopoiesis and implication in pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS are summarized in Table 1. Most del(5q) patients have deletions that span both CDRs, therefore, simultaneous deletion of genes on both CDRs may cooperate to contribute to altered hematopoiesis seen in patients.

|

Gene |

Location |

Effect of deletion |

Phonotype |

Reference |

|

CDC25C, PP2A |

Proximal CDR |

Defective G2-M phase regulation |

G1 and G2M arrest and apoptosis |

[45] |

|

CTNNA1 |

Proximal CDR |

Adherens junction synthesis, signal transduction |

Impact multiple cancer types, affect progression of bone marrow dysplasia and AML |

[46] |

|

DIAPH1 |

Proximal CDR |

Defective cytoskeleton, tumor suppression |

Clonal dominance, macrothrombocytopenia, enhance MDS phenotype, hearing loss, microcephaly |

[47-49] |

|

EGR1 |

Proximal CDR |

Decrease in tumor suppressors |

Leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia |

[45] |

|

HSPA9 |

Proximal CDR |

Heat shock protein |

Anemia, B cell abnormalities |

[12,29-31] |

|

CSNK1A1 |

Distal CDR |

Enables protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

RBC proliferation and expansion, abnormal myeloid progenitor expansion |

[19,20] |

|

miR-145, miR-146 |

Distal CDR |

Elevated innate immune signaling |

Thrombocytosis, neutropenia, megakaryocytic dysplasia |

[45] |

|

RPS14 |

Distal CDR |

Defective ribosomal processing |

Macrocytic anemia |

[15-17,45] |

|

SPARC |

Distal CDR |

Increased cell adhesion |

Thrombocytopenia, anemia |

[45] |

MDS and Anemia

Anemia is the most common clinical manifestation of MDS patients and present in the majority of MDS cases. Anemia in MDS is not only a transient manifestation, but also a disease similar to the situation of congenital anemias. The pathophysiologic causes of anemia include the dysplasia of erythopoietic progenitors and the abnormal HSCs losing their ability to mature into RBCs [21]. It has been demonstrated that the formation of lipid raft microdomains, assembling erythropoietin (EPO) receptor, STAT5, JAK2, and Lyn kinases, are key regulators of EPO signaling and erythroid maturation [22]. The plasma membrane of hematopoietic cells contains sphingolipid and cholesterol enriched microdomains called lipid rafts, which serve as cluster signaling intermediates to create focused signaling platforms that facilitate receptor-induced activation of signal transduction molecules. It has been observed that MDS erythroid progenitors display a significantly diminished lipid raft assembly and smaller raft aggregates, suggesting disruption of raft integrity may be responsible for the impaired EPO signaling in MDS [23] Although MDS dysplastic erythroid progenitor cells may express EPO receptor at a normal density, in vitro studies showed that the signaling pathway in response to EPO stimulation is defective, such as lack of STAT5 phosphorylation [24]. In addition, Frisan et al. reported that defective ERK1/2 phosphorylation upon EPO stimulation signaling is altered in MDS progenitors [25]. For the clinical treatment of anemia in del(5q) MDS patients, multiple strategies have been used including blood transfusion, iron chelation therapy, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) [5,22].

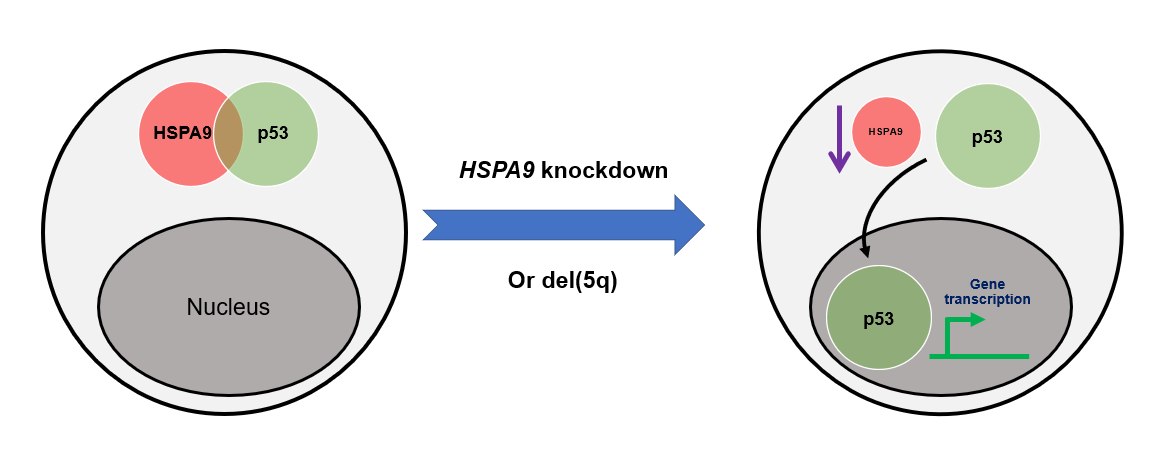

The HSPA9 gene encodes the protein mortalin, and its location is mapped to 5q31.2, a region located in the proximal CDR of the del(5q) MDS region [26]. The HSPA9/mortalin is a highly conserved heat-shock chaperone belonging to the heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) family. It is predominantly presented in the mitochondria, but also found in other sub-cellular compartments including plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and cytosol [27]. HSPA9/mortalin is critical in regulating a variety of cell physiological functions such as response to cell stress, control of cell proliferation, and inhibition/prevention of apoptosis [28]. Our laboratory has been studying the role of HSPA9 gene in haematopoiesis and erythroid maturation for years. We observed that Hspa9 homozygous deletion mice are embryonic lethal, while Hspa9 heterozygous deletion mice have normal basal hematopoiesis, but display altered B-cell lymphopoiesis [29]. This is consistent with our later reports showing that haploinsufficiency of multiple del(5q) genes, including Hspa9, also induce B-cell abnormalities in mice [12]. In addition to using mouse models, we have identified that HSPA9 knockdown induces apoptosis in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells, which is likely a TP53-dependent process, suggesting that reduced levels of HSPA9 may contribute to p53/TP53 activation and increased apoptosis observed in del(5q) MDS (Figure 2) [30]. More recently, we reported that HSPA9/mortalin inhibition disrupts erythroid maturation through a TP53-dependent mechanism in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells [31]. This study indicates that insufficiency of specific del(5q) MDS-associated gene could disrupt erythroid maturation, providing insights into ineffective erythropoiesis and anemia observed in patients.

Figure 2: Model of the mechanism of TP53/p53 activation following HSPA9 knockdown. HSPA9 interacts with and stabilizes p53 in the cytoplasm of cells. HSPA9 reduction leads to the dissociation of p53 from the HSPA9-p53 cytoplasmic complex. Translocation of p53 from cytoplasm into nucleus activates downstream gene transcription which is regulated by TP53/p53.

Future Studies

The precise relationship between erythroid maturation, TP53, and HSPA9 remains unclear. For future studies, there are at least four directions that we can pursue to elucidate the mechanisms. First, we plan to investigate the energy metabolism during the erythroid maturation process. Energy metabolism includes two main pathways: glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Glycolysis takes place in cytosol and converts glucose into pyruvate and to produce ATP and NADH. Oxidative phosphorylation takes place in mitochondria and uses energy released through the TCA cycle to produce ATP with higher efficiency than glycolysis [32]. In the human blood system, HSCs and progenitor cells possess the ability of both differentiation (into downstream mature blood cells) and self-renewal (proliferation without differentiation). It was suggested that a balance between glycolysis and OXPHOS metabolism could guide the choice between differentiation and self-renewal in stem cell fate [33]. Glycolysis was shown to be characteristic of self-renewing stem and progenitor cells, while there is a switch from glycolytic metabolism toward OXPHOS during cell differentiation [33,34]. Specifically, Richard et al. reported that erythroid differentiation requires a peak of energy consumption associated with glycolytic metabolism rearrangements, in which glycolysis is less involved in differentiating erythroid cells compared to OXPHOS [35]. The relationship between HSPA9/mortalin and glycolytic metabolism has been studied by other groups. Echtenkamp et al. showed that pharmacological inhibition of mortalin by JG-98, an allosteric inhibitor of HSP70, could resensitize castration-resistant prostate cancer to androgen deprivation drugs by suppressing aerobic respiration. JG-98’s primary effect is to inhibit mitochondrial translation, leading to disruption of electron transport chain activity [36]. Ferguson et al. found that JG-98 could increase the potency against myeloma cells resistant to proteasome inhibitors. JG-98 could localize to mitochondria, inhibit mortalin, and deplete mitochondrial ribosome proteins [37]. Our published data showed that HSPA9/mortalin inhibition disrupts erythroid maturation through a TP53-dependent mechanism [30,31]. We expect that that the TP53-dependent regulation of erythroid maturation by HSPA9/mortalin is through glycolic metabolism modification, more specifically, inhibiting glycolysis and enhancing OXPHOS (Figure 1). Second, Chen et al. defined the stages during erythroid differentiation based on dynamic changes in the expression of red cell membrane proteins such as maturation such as Band3, CD44, CD71, spectrin, and beta-actin [38]. Thus, it is worth to investigate whether HSPA9 is involved in the process of red cell membrane development, which is critical for erythroid maturation. Third, we also showed that HSPA9 knockdown inhibits Stat5 activation in vitro in the presence of IL-7 [29]. Stat5a and 5b homozygous deletion mice showed ineffective erythropoiesis due to decreased survival of early erythroblasts [39]. Hence, HSPA9 could possibly regulate erythroid maturation through STAT5 signaling. Fourth, Ganguli et al. reported that p53 inhibits glucocorticoid-induced proliferation of erythroid progenitors, suggesting that TP53 may inhibit erythropoiesis which is consistent with our hypothesized model in Figure 1 [40]. Interestingly, human HSPA9 gene and glucocorticoid receptor gene (known as NR3C1) are both located on chromosome 5q31 [41,42]. Thus, HSPA9/mortalin may interact with glucocorticoid receptors, which mediates erythropoiesis through TP53 regulation. In addition, other studies showed that glucocorticoid receptor-Stat5 interaction in hepatocytes controls body size and maturation-related gene expression in mice [43,44]. Therefore, it is also worth to explore whether STAT5 signaling could potentially be triggered by HSPA9 and glucocorticoid in erythropoiesis.

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 2U54GM104942-08 (Tuoen Liu). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported in part by NIH grant P20GM103434 to the West Virginia IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence. This study was also supported by West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine intramural fund (Tuoen Liu).

Author Contributions Statement

Alfredo Fallorina and Tuoen Liu wrote, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

2. Lee JM, Suh JS, Kim YK. Red Blood Cell Deformability and Distribution Width in Patients with Hematologic Neoplasms. Clinical Laboratory. 2022 Oct 1;68(10).

3. Fenaux P, Platzbecker U, Mufti GJ, Garcia-Manero G, Buckstein R, Santini V, et al. Luspatercept in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 Jan 9;382(2):140-51.

4. Yuen LD, Hasserjian RP. Morphologic Characteristics of Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2023 Dec 1;43(4):577-96.

5. PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Myelodysplastic Syndromes Treatment (PDQ®): Patient Version. 2023 Nov 17. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002.

6. Gurnari C, Piciocchi A, Soddu S, Bonanni F, Scalzulli E, Niscola P, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes with del (5q): a real-life study of determinants of long-term outcomes and response to lenalidomide. Blood Cancer Journal. 2022 Sep 7;12(9):132.

7. Liang HP, Luo XC, Zhang YL, Liu B. Del (5q) and inv (3) in myelodysplastic syndrome: A rare case report. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2022 Apr 4;10(11):3601-8.

8. List A, Ebert BL, Fenaux P. A decade of progress in myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. Leukemia. 2018 Jul;32(7):1493-9.

9. Boultwood J, Fidler C, Strickson AJ, Watkins F, Gama S, Kearney L, et al. Narrowing and genomic annotation of the commonly deleted region of the 5q− syndrome. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2002 Jun 15;99(12):4638-41.

10. Bruzzese A, Martino EA, Mendicino F, Lucia E, Olivito V, Capodanno I, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes del (5q): Pathogenesis and its therapeutic implications. European Journal of Haematology. 2024 Jan 31.

11. Adema V, Palomo L, Walter W, Mallo M, Hutter S, La Framboise T, et al. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications of molecular profiles resultant from deletion 5q. EBioMedicine. 2022 Jun 1;80:104059.

12. Liu T, Ahmed T, Krysiak K, Shirai CL, Shao J, Nunley R, et al. Haploinsufficiency of multiple del (5q) genes induce B cell abnormalities in mice. Leukemia Research. 2020 Sep 1;96:106428.

13. Fuchs O. Important genes in the pathogenesis of 5q-syndrome and their connection with ribosomal stress and the innate immune system pathway. Leukemia Research and Treatment. 2012;2012:179402.

14. Ribezzo F, Snoeren IA, Ziegler S, Stoelben J, Olofsen PA, Henic A, et al. Rps14, Csnk1a1 and miRNA145/miRNA146a deficiency cooperate in the clinical phenotype and activation of the innate immune system in the 5q-syndrome. Leukemia. 2019 Jul;33(7):1759-72.

15. Hu S, Cai J, Fang H, Chen Z, Zhang J, Cai R. RPS14 promotes the development and progression of glioma via p53 signaling pathway. Experimental Cell Research. 2023 Feb 1;423(1):113451.

16. Pellagatti A, Hellström‐Lindberg E, Giagounidis A, Perry J, Malcovati L, Della Porta MG, et al. Haploinsufficiency of RPS14 in 5q− syndrome is associated with deregulation of ribosomal‐and translation‐related genes. British Journal of Haematology. 2008 Jul;142(1):57-64.

17. Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J, Chang CY, Tamayo P, Galili N, et al. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q-syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008 Jan 17;451(7176):335-9.

18. Dutt S, Narla A, Lin K, Mullally A, Abayasekara N, Megerdichian C, et al. Haploinsufficiency for ribosomal protein genes causes selective activation of p53 in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2011 Mar 3;117(9):2567-76.

19. Schneider RK, Adema V, Heckl D, Järås M, Mallo M, Lord AM, et al. Role of casein kinase 1A1 in the biology and targeted therapy of del (5q) MDS. Cancer Cell. 2014 Oct 13;26(4):509-20.

20. Liu X, Huang Q, Chen L, Zhang H, Schonbrunn E, Chen J. Tumor-derived CK1α mutations enhance MDMX inhibition of p53. Oncogene. 2020 Jan 2;39(1):176-86.

21. Steensma DP, Heptinstall KV, Johnson VM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Camoriano JK, et al. Common troublesome symptoms and their impact on quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): results of a large internet-based survey. Leukemia Research. 2008 May 1;32(5):691-8.

22. Santini V. Anemia as the main manifestation of myelodysplastic syndromes. Seminars in Hematology. 2015 Oct 1;52(4):348-56.

23. McGraw KL, Fuhler GM, Johnson JO, Clark JA, Caceres GC, Sokol L, et al. Erythropoietin receptor signaling is membrane raft dependent. PloS one. 2012 Apr 3;7(4):e34477.

24. Parisi S, Finelli C, Fazio A, De Stefano A, Mongiorgi S, Ratti S, et al. Clinical and molecular insights in erythropoiesis regulation of signal transduction pathways in myelodysplastic syndromes and β-thalassemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Jan 15;22(2):827.

25. Kornblau SM, Cohen AC, Soper D, Huang YW, Cesano A. Age‐related changes of healthy bone marrow cell signaling in response to growth factors provide insight into low risk MDS. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry. 2014 Nov;86(6):383-96.

26. Shan Y, Cortopassi G. Mitochondrial Hspa9/Mortalin regulates erythroid differentiation via iron-sulfur cluster assembly. Mitochondrion. 2016 Jan 1;26:94-103.

27. Ryu J, Kaul Z, Yoon AR, Liu Y, Yaguchi T, Na Y, et al. Identification and functional characterization of nuclear mortalin in human carcinogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014 Sep 5;289(36):24832-44.

28. Londono C, Osorio C, Gama V, Alzate O. Mortalin, apoptosis, and neurodegeneration. Biomolecules. 2012 Mar 1;2(1):143-64.

29. Krysiak K, Tibbitts JF, Shao J, Liu T, Ndonwi M, Walter MJ. Reduced levels of Hspa9 attenuate Stat5 activation in mouse B cells. Experimental Hematology. 2015 Apr 1;43(4):319-30.

30. Liu T, Krysiak K, Shirai CL, Kim S, Shao J, Ndonwi M, et al. Knockdown of HSPA9 induces TP53-dependent apoptosis in human hematopoietic progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 8;12(2):e0170470.

31. Butler C, Dunmire M, Choi J, Szalai G, Johnson A, Lei W, et al. HSPA9/mortalin inhibition disrupts erythroid maturation through a TP53-dependent mechanism in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2024 Apr 1;29(2):300-11.

32. Zheng JI. Energy metabolism of cancer: Glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation. Oncology Letters. 2012 Dec 1;4(6):1151-7.

33. Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self‐renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2010 Nov;2(6):640-53.

34. Wang YH, Scadden DT. Targeting the Warburg effect for leukemia therapy: Magnitude matters. Molecular & Cellular Oncology. 2015 Jul 3;2(3):e981988.

35. Richard A, Vallin E, Romestaing C, Roussel D, Gandrillon O, Gonin-Giraud S. Erythroid differentiation displays a peak of energy consumption concomitant with glycolytic metabolism rearrangements. PLoS One. 2019 Sep 4;14(9):e0221472.

36. Echtenkamp FJ, Ishida R, Rivera-Marquez GM, Maisiak M, Johnson OT, Shrimp JH, et al. Mitoribosome sensitivity to HSP70 inhibition uncovers metabolic liabilities of castration-resistant prostate cancer. PNAS nexus. 2023 Apr 1;2(4):pgad115.

37. Ferguson ID, Lin YH, Lam C, Shao H, Tharp KM, Hale M, et al. Allosteric HSP70 inhibitors perturb mitochondrial proteostasis and overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance in multiple myeloma. Cell Chemical Biology. 2022 Aug 18;29(8):1288-302.

38. Chen K, Liu J, Heck S, Chasis JA, An X, Mohandas N. Resolving the distinct stages in erythroid differentiation based on dynamic changes in membrane protein expression during erythropoiesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 Oct 13;106(41):17413-8.

39. Smith MR, Satter LR, Vargas-Hernández A. STAT5b: A master regulator of key biological pathways. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023 Jan 23;13:1025373.

40. Ganguli G, Back J, Sengupta S, Wasylyk B. The p53 tumour suppressor inhibits glucocorticoid-induced proliferation of erythroid progenitors. EMBO Reports. 2002 Jun 1;3(6):569-74.

41. Chang X, Ji C, Zhang T, Huang H. Prenatal to preimplantation genetic diagnosis of a novel compound heterozygous mutation in HSPA9 associated with Even-Plus syndrome. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2024 Mar 1;555:117803.

42. Emadali A, Hoghoughi N, Duley S, Hajmirza A, Verhoeyen E, Cosset FL, et al. Haploinsufficiency for NR3C1, the gene encoding the glucocorticoid receptor, in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2016 Jun 16;127(24):3040-53.

43. Wingelhofer B, Neubauer HA, Valent P, Han X, Constantinescu SN, Gunning PT, et al. Implications of STAT3 and STAT5 signaling on gene regulation and chromatin remodeling in hematopoietic cancer. Leukemia. 2018 Aug;32(8):1713-26.

44. Engblom D, Kornfeld JW, Schwake L, Tronche F, Reimann A, Beug H, et al. Direct glucocorticoid receptor–Stat5 interaction in hepatocytes controls body size and maturation-related gene expression. Genes & Development. 2007 May 15;21(10):1157-62.

45. Giagounidis A, Mufti GJ, Fenaux P, Germing U, List A, MacBeth KJ. Lenalidomide as a disease-modifying agent in patients with del (5q) myelodysplastic syndromes: linking mechanism of action to clinical outcomes. Annals of Hematology. 2014 Jan;93:1-11.

46. Huang J, Wang H, Xu Y, Li C, Lv X, Han X, et al. The role of CTNNA1 in malignancies: An updated Review. Journal of Cancer. 2023;14(2):219-30.

47. Stritt S, Nurden P, Turro E, Greene D, Jansen SB, Westbury SK, et al. A gain-of-function variant in DIAPH1 causes dominant macrothrombocytopenia and hearing loss. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2016 Jun 9;127(23):2903-14.

48. DeWard AD, Leali K, West RA, Prendergast GC, Alberts AS. Loss of RhoB expression enhances the myelodysplastic phenotype of mammalian diaphanous-related Formin mDia1 knockout mice. PloS one. 2009 Sep 21;4(9):e7102.

49. Ercan-Sencicek AG, Jambi S, Franjic D, Nishimura S, Li M, El-Fishawy P, et al. Homozygous loss of DIAPH1 is a novel cause of microcephaly in humans. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2015 Feb;23(2):165-72.