Abbreviations

MHC: Major Histocompatibility Complex; ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor; IL6: Interleukin 6; irAEs: Immune-Related Adverse Events; n-irAEs: Neurological Immune Related Adverse Events; NfL: Neurofilament Light Chain; PD-1: Programmed Death-1; PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1; PNS : Praneoplastic Syndrome

Introduction

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have transformed the scope of cancer treatment [1,2]. Atezolizumab, is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) to block its interaction with PD-1 and B7-1 receptors, thereby reinstating T cell response [3,4]. The therapeutic use of atezolizumab has expanded rapidly [5], demonstrating promising anti-tumor activity in patients with lung cancer, urothelial and hepatocellular carcinomas, and making it the first ICI approved for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer [1,3,4,6,7]. Despite its benefits, atezolizumab is associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs), that can impact multiple organs. Studies have identified skin eruptions as the most common irAEs, followed by interstitial lung disease, thyroid disorders, and liver dysfunction [8]. Most atezolizumab-induced irAEs are mild to moderate, resolving with ICI discontinuation or manageable by corticosteroids [5,9]. However, among the irAEs, neurotoxicities, although rare [10], are of particular concern due to their severity and high risk of long-term disability and fatalities [11-13]. These neurological irAEs (n-irAEs) are increasingly recognized, encompassing a wide range of nervous system symptoms [14]. A thorough understanding of these toxicities is crucial for early diagnosis and effective management, which are required to improve patient outcomes and reduce morbidity [2,11,15].

With the increasing use of atezolizumab, ongoing assessment of its safety profile, notably neurotoxicity, is critical. This commentary builds on our previous review of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity. Our objective is to provide recent data, examine if unresolved questions have been addressed, and explore advances in the understanding of physiopathological mechanisms.

Summary of the Focal Review

Major findings

Symptoms of neurotoxicity induced by atezolizumab typically emerge two weeks after the last administration, with 37.8% of cases showing onset after the first treatment cycle. Among n-irAEs, encephalitis has been the most extensively documented adverse reaction in case studies. Numerous reports have highlighted atezolizumab-induced encephalitis across various types of cancers, which can present in multiple forms. This suggests that encephalitis is not only a severe adverse effect, but also one that warrants caution when prescribing atezolizumab. Neuropathy is another commonly reported event following atezolizumab treatment and a prelevant adverse reaction across clinical trials. Improvement in symptoms or complete recovery occurs in the majority of cases (82.6%), with some patients successfully rechallenged with atezolizumab or switched to a different ICI class. However, few patients experienced a recurrence of symptoms even after periods of remission following drug withdrawal. Fatal outcomes have been reported, particularly in cases involving encephalitis and multiple sclerosis [16].

Limitations and unanswered questions

The literature reviewed on atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity primarily consists of case series, individual case reports, and retrospective studies, which limits the findings to descriptive observations and restricts a thorough investigation of potential risk factors. While short?term toxicities have been relatively well documented, long?term effects remain largely unclear. There is a notable lack of comprehensive assessments regarding the clinical progression of n-irAEs, particularly chronic cases that have not been well characterized. The focus thus far has been on the acute phase of n-irAEs, due to its dramatical clinical presentation and the urgent need for treatment; however, knowledge about the clinical course beyond this phase is insufficient. Moreover, the observational nature of these reports does not permit definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of specific management strategies, and no established guidelines currently exist. Understanding the mechanisms of neurotoxicity, as well as implementing risk stratification and early diagnosis in patient populations, is crucial for balancing the risk-benefit ratio of treatment and developing targeted strategies for managing irAEs without compromising tumour outcomes. Additionnally, many studies lack a standardized grading for event severity and do not consistently eliminate alternative causes, which undermines the ability to establish strong causal relationships. As more patients undergo ICI therapy, a clearer clinical picture regarding efficacy and toxicity will emerge. Important questions remain about the true incidence and extent of neurotoxicity associated with atezolizumab, highlighting the need for further research into its underlying pathophysiology. Although the mechanisms of toxicity warrant attention, specific risk stratification protocols have yet to be developed. In this commentary, we will explore these limitations and seek to address these unanswered questions through recent literature.

Recent updates

In this commentary, we have reviewed the recent literature to highlight new cases and studies on atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity.

Our updated literature review identified three additional case reports, including one case each of encephalitis, cereballar atxia and a combined encephalitis with neuropathy [11,15,17]. The clinical presentation, laboratory results, and imaging findings in these cases aligned with previously documented cases (Table 1) [16]. Additionally, a recent retrospective analysis of n-irAEs associated with atezolizumab confirmed prior findings, revealing that encephalitis had the highest reporting ratio (93.4), followed by peripheral neuropathy (23.9), myasthenia gravis (10.4), Guillain-Barre syndrome (8.9), meningitis (7.2) and transverse myelitis (5.5) [2].

|

Type of study |

First author, year (number of patients) |

Gender |

Age |

Type of malignant tumor |

Treatment course and dosage |

Type of neurotoxicity |

Number of cycles |

Delay of onset |

Clinical symptoms |

Paraclinical investigations |

Management options |

Outcome (within) |

|

Case report |

Farina, 2024 (1) [17] |

M |

52 |

SCLC |

ATZ 1200 mg |

Cerebellar ataxia |

23rd |

NS |

opsoclonus, dysarthria, bilateral appendicular, truncal and gait ataxia |

Brain MRI: mild cerebellar atrophy EEG: normal CSF: no malignant cells Blood and CSF cultures: negative |

IV methylprednisolone and immunoglobulin |

Improvement (3 months) |

|

Case report |

Otomo, 2024 (1) [15] |

M |

65 |

HCC |

NA |

Encephalitis |

NA |

NA |

Fever, difficulty in moving, and aphasia |

Imaging and CSF analysis: no signs of infection or malignancy |

Steroid pulse therapy |

Improvement with slight paralysis of legs Treatment resumed |

|

Case report |

Sagong, 2024 (1) [11] |

M |

45 |

HCC |

ATZ 1200 mg + BVZ15 mg/kg |

Encephalitis + polyneuropathy |

1st |

13 days |

Fever, headache, confusion, general epileptic seizures, motor weakness |

CSF: no malignant cells Brain MRI: diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement Spine MRI: no abnormalities EEG:no epileptiform discharge Blood cultures and PCR for viruses: negative EMG: sensorimotor polyneuropathy |

Mechanical ventilation Steroids |

Initial improvement Relapse of seizures Recovery (66 days)

|

|

SCLC: Small Cell Lung Cancer; ATZ : Atezolizumab; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; EEG: Electroencephalogram; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; IV: Intravenous; NS: Not Specified; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; NA: Not Accessed; BVZ: Bevacizumab;; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; EMG: Electromyography |

||||||||||||

Neurological ir-AEs affecting cranial nerves are initially underreported in the literature. A recent meta-analysis examining cranial nerve involvement with ICIs identified facial nerve involvement as most common (38%), followed by the optic nerve (35%), cochleovestibular (12%), and abducens nerve (10%). Notably, 52% of patients had bilateral cranial nerve involvement while multiple nerve involvement was rare (12%). Anti- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) agents were most commonly linked to facial nerve involvement, whereas oculomotor involvement was exclusive to patients on anti-PD-1/PDL-1. The median interval from the first ICI injection to onset of nerve palsy was approximately 10 weeks. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the highest sensitivity in detecting optic nerve involvement (55%) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis in 59% of cases, with a significant correlation to facial nerve involvement [10].

Moreover a nationwide multicenter study examined the progression of n-irAEs associated with ICIs, finding that patients with chronic active n-irAEs had a significantly poor prognosis than those with single episode toxicity. Chronic cases exhibited a higher incidence of severe neurological disability (38% vs 4%) and increased mortality (50% vs 4%), underscoring the serious long-term impact of these events [12].

Advancements in mechanism and physiopathology

ICI-associated irAEs are thought to result excessive T cell activation [18]. In fact, while ICIs enhance T-cell activity against tumor antigens, this same mechanism can lead to toxicity when T cells mistakenly target non-tumor antigens: In the central nervous system (CNS), such inappropriate T-cell activation causes inflammation and damage to healthy brain and spinal cord tissues leading to neurotoxicity [19,20].

Despite this general understanding, there has been limited advancement in elucidating the precise physiopathological mechanisms underlying ICI induced neurotoxicity. Recent studies have not yet specifically focused on individual types of neurotoxicity or the pathways by which ICIs contribute to their developement. Consequently, knowledge in this area remains limited, and further research is needed to determine if there are specific mechanisms tied to particular neurotoxicities or unique to individual ICI classes.

Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

Recognizing n-irAEs is challenging due to the broad diferential diagnosis of neurological symptoms in oncology patients and the overlapping syndromes with atypical presentations. Clinicians worldwide are variably involved in managing n-irAEs, leading to highly inconsistent diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. While recent consensus guidelines have been published for the diagnosis and management of irAEs, the level of evidence on these rare toxicities remains limited [14].

The severity and type of irAEs are crucial in guiding treatment, with guidelines from various societies all emphasizing a tailored approach based on toxicity severity. Treatment for ICI-induced n-irAES typically includes ICI discontinuation across all severity levels: temporary discontinuation with corticosteroids for Grades 1 and 2, high-dose corticosteroids for Grade 3, and permanent discontinuation for most Grade 4 toxicities [20]. If symptoms do not resolve, plasmapheresis may be used to neutralize ICIs [11]. The median duration for steroid therapy is approximately three months but can extend up to 12 months in cases of chronic active n-irAEs [12].

Despite these guidelines, corticosteroid response is inconsistent, and management strategies for corticosteroid-refractory patients remain inclear. The severity of these events and the uncertainties surrounding their diagnosis and management highlight an urgent need for reliable biomarkers to aid in early recognition, accurate diagnosis, outcome prediction and effective therapeutic interventions.

Rechallenge of ICIs

Serious n-irAEs are considered a major contraindication for resuming ICIs. However, addressing the clinical needs of patients who discontinue ICIs due to such adverse effects remains a key challenge in oncology research. In response, the concept of ICI rechallenge has gained attention based on the rationale that patients who previously responded to treatment may still harbor ICI-sensitive tumor cells. Additionally, the dynamic nature of the immune system and the complex tumor microenvironment may allow for a renewed anti-tumor response, especially when alternative therapies are limited.

Our previous review reported successful rechallenges in cases of n-irAEs, both with the same ICI and after switching to a different ICI class [20]. Pharmacovigilance data further suggest that the recurrence rate of neurotoxicities is relatively low after ICI reintroduction compared to other irAEs. However, evidence remains limited, and the risk of relapse should not be underestimated [14]. Due to this limited data and the absence of large-scale prospective studies, ICI rechallenge has not yet fully transitioned into standard clinical practice.

Notably, in non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), ICI rechallenge has shown survival benefits, even in cases with severe prior neurotoxicity, without significant rise in recurrent irAEs [20]. A recent meta-analysis observed ICI rechallenge in patients with a single episode of n-irAEs (22%), less commonly, in those with chronic active n-irAEs (12%) with no recorded neurological relapses [12].

Moreover, factors like the timing, severity, and initial management strategy of irAE influence the risk of relapse; some studies suggest that a shorter interruption period may increase this risk, although findings are different [20].

Patient monitoring and safety (risk factors and biomarkers)

Recognizing the importance of each patient's individual immune and genetic characteristics is increasingly essential for predicting and minimizing recurrence risk in irAEs linked to ICIs. Deeper insights into risk factors and biomarkers with predictive value for irAEs during rechallenge will support clinicians in making informed decisions on ICI rechallenge strategies [20]. For instance, adding L-carnitine to the ICI treatment plan helped prevent myasthenia gravis recurrence in a thymoma patient with a genetic mutation, affecting carnitine metabolism [21].

Research has also highlighted genetic influences on susceptibility, such as specific variants in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and certain T cell receptors [19]. The HLA-B*27:05 allele, which is relatively rare in the general population, has been associated with meningoencephalitis in patients treated with atezolizumab [22]. Additionally, recent studies identified auto-antibodies linked to hypophysitis; specifically anti?GNAL and anti?ITM2B may serve as useful biomarkers [19].

Neural antibodies have also been investigated for their clinical relevance [17]. More than 80% of patients with focal ICI-induced encephalitis present paraneoplastic syndrome (PNS) antibodies, particularly Hu and Ma2, while cases of meningoencephalitis tend to lack these antibodies. PNS antibodies were associated with reduced treatment response and higher mortality, whereas GFAP or neuron-surface antibodies correlated with improved outcomes. Brain-targeting antibodies of unknown specificities were also noted in 20% of ICI-encephalitis cases, although their broader diagnostic role remains under study [22].

Biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NfL), indicating neuroaxonal damage, have shown promise in differentiating ICI-induced encephalitis from controls with reported sensitivities and specificities between 74 and 88%. However, elevated NfL levels can mirror thoses in herpetic-encephalitis. Serum S100B levels, indicating CNS injury, increase early in case of central ICI neurotoxicity, and may serve as an early indicator, though additional confounding factors must be considered [22].

Emerging cytokine profiles may also help predict severe irAEs. Limited data suggest that patients with severe ICI-neurotoxicities exhibit significantly elevated levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), with some patients also showing higher levels of interleukin 6 (IL6). IL-6 involvement in ICI-induced myositis and other non-CNS irAEs hints at its potential role in ICI-encephalitis, although its function as biomarker remains unclear. Small cohort studies have reported elevated levels of other cytokines, such as IL-8, CXCL-10, and CXCL-13 in CSF of ICI-encephalitis patients, warranting further research to validate these findings [22,23].

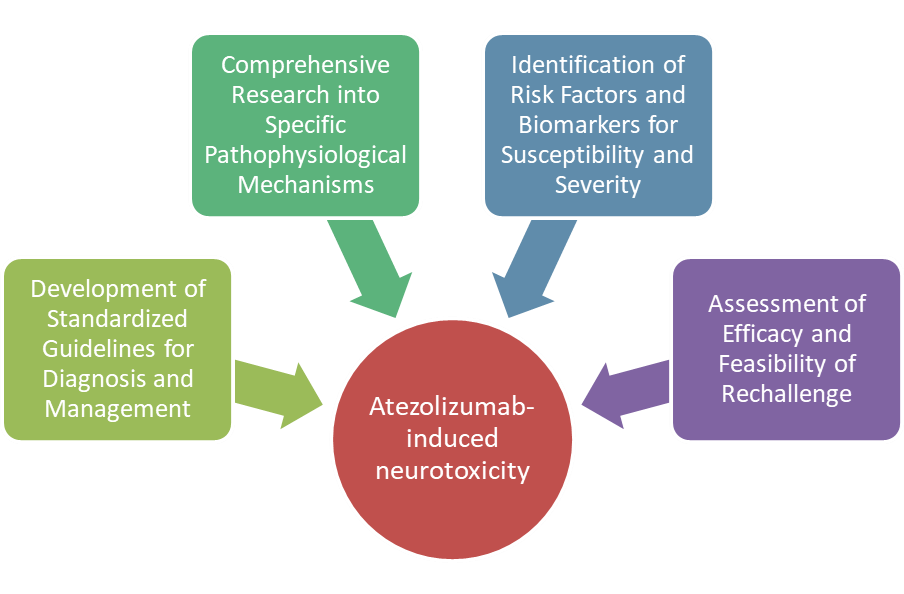

Conclusions and Future directions

Treatment with ICIs has revolutionized cancer therapy over the past decade. However, the irAEs associated with these agents present unique challenges for clinical management. While irAEs are understood to result from the intended reactivation of the immune response following ICI therapy, the specific host and tumor factors contributing to these events remain unclear. Current guidelines emphasize the severity of irAEs and advocate for the development of predictive biomarkers to identify patients at increased risk for such toxicities and inform theraapeutic decisions. Analyzing cytokine levels and their dynamics in ICI related n-irAEs may provide insights into the underlying immunopathology and suggest novel therapeutic targets. Longitudinal studies involving large cohorts will be essential for establishing reliable thresholds and clarifying the specificity and clinical utility of these biomarkers. Despite ongoing efforts to elucidate the mechanisms behind these neurotoxicities, reliable biomarkers and predictive risk factors have yet to be identified.

Therefore, further epidemiological studies are necessary to enhance understanding and quantification of these adverse events. Additionally, research is needed to explore the molecular mechanisms responsible for these events so to enable accurate prediction and effective management. Future investigations should focus on characterizing the clinical features and pathophysiology of chronic n-irAEs, particularly since patients with chronic n-irAEs face a higher risk of mortality related to cancer progression. Thus, prospective studies are warranted to assess the safety of long-term immunosuppression and ICI rechallenge in this population.

References

2. Frey C, Etminan M. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Atezolizumab: Insights from Real-World Pharmacovigilance Data. Antibodies (Basel). 2024 Jul 15;13(3):56.

3. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 14;382(20):1894-905.

4. Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 6;379(23):2220-9.

5. Bhardwaj M, Chiu MN, Pilkhwal Sah S. Adverse cutaneous toxicities by PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: pathogenesis, treatment, and surveillance. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2022 Mar;41(1):73-90.

6. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Csőszi T, Vynnychenko I, Goloborodko O, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021 Oct 9;398(10308):1344-57.

7. Kwapisz D. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021 Mar;70(3):607-617.

8. Hayashi H, Nishio M, Akamatsu H, Goto Y, Miura S, Gemma A, et al. Association between Immune-Related Adverse Events and Atezolizumab in Previously Treated Patients with Unresectable Advanced or Recurrent Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Research Communications. 2024 Nov 1;4(11):2858-67.

9. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Nishio M, Mok TS, Reck M, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with efficacy of atezolizumab in patients with non–small cell lung cancer: pooled analyses of the phase 3 IMpower130, IMpower132, and IMpower150 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncology. 2023 Apr 1;9(4):527-35.

10. Pichon S, Aigrain P, Lacombe C, Lemarchant B, Ledoult E, Koether V, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-associated cranial nerves involvement: a systematic literature review on 136 patients. J Neurol. 2024 Oct;271(10):6514-25.

11. Sagong M, Kim KT, Jang BK. Atezolizumab-and bevacizumab-induced encephalitis in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2024 Aug 24;150(8):397.

12. Rossi S, Farina A, Malvaso A, Dinoto A, Fionda L, Cornacchini S, et al. Clinical Course of Neurologic Adverse Events Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Focus on Chronic Toxicities. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024 Nov;11(6):e200314.

13. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S, Menzer C, Ye F, et al. Fatal Toxic Effects Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 1;4(12):1721-8.

14. Diamanti L, Picca A, Bini P, Gastaldi M, Alfonsi E, Pichiecchio A, et al. Characterization and management of neurological adverse events during immune-checkpoint inhibitors treatment: an Italian multicentric experience. Neurol Sci. 2022 Mar;43(3):2031-41.

15. Otomo K, Fujita M, Sekine R, Sato H, Abe N, Sugaya T, et al. A Case of Patient with Atezolizumab-induced Encephalitis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Intern Med. 2024 Sep 11. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.4321-24.

16. Salem MY. Atezolizumab Induced Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review. Journal of Experimental Neurology. 2024 Jul 22;5(3):121-40.

17. Farina A, Villagrán-García M, Benaiteau M, Lamblin F, Fourier A, Honnorat J, et al. Opsoclonus-Ataxia Syndrome in a Patient With Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024 Sep;11(5):e200287.

18. Mavadia A, Choi S, Ismail A, Ghose A, Tan JK, Papadopoulos V, et al. An overview of immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicities in bladder cancer. Toxicol Rep. 2024 Sep 11;13:101732.

19. Mangan BL, McAlister RK, Balko JM, Johnson DB, Moslehi JJ, Gibson A, et al. Evolving insights into the mechanisms of toxicity associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Sep;86(9):1778-89.

20. Gang X, Yan J, Li X, Shi S, Xu L, Liu R, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer: Current evidence and future directions. Cancer Lett. 2024 Nov 1;604:217241.

21. Gao W, Wu L, Jin S, Li J, Liu X, Xu J, et al. Rechallenge of immune checkpoint inhibitors in a case with adverse events inducing myasthenia gravis. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Nov;10(11):e005970.

22. Farina A, Villagrán-García M, Joubert B. Soluble biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitor-related encephalitis: A mini-review. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2024 Nov;180(9):982-8.

23. Madjar K, Mohindra R, Durán-Pacheco G, Rasul R, Essioux L, Maiya V, et al. Baseline risk factors associated with immune related adverse events and atezolizumab. Front Oncol. 2023 Feb 28;13:1138305.