Abbreviations

BCS: Birmingham Calcium Score; CTCA: Computed tomography Coronary Angiography; CVI: Calcium Volume Index; I/C: Intra Coronary; IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound; IVL: Intravascular Lithotripsy; OCT: optical Coherence Tomography; nc: non-compliant

Introduction

Coronary artery calcification is an independent cardiovascular risk factor, influenced by patient demographics and older age [1-3]. Optimal stent expansion is limited by poorly modified calcified coronary lesions resulting in increased risk of in-stent restenosis and stent thrombosis [4]. Coronary angiography and intracoronary imaging are utilized to assess the degree of calcification and choose the required tool for calcium modification. In addition, Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography (CTCA) can identify and risk-stratify patients based on coronary calcification [5-8].

Calcium modification tools include scoring balloons, cutting balloons, high pressure OPN non-compliant balloons, rotational atherectomy and the recently introduced Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL) balloon [9]. In the United Kingdom (UK), orbital atherectomy is not available as a calcium modification tool.

Coronary Calcification, Intracoronary Imaging and Calcium Modifying Tools

Angiographic calcification

CTCA can demonstrate calcification of the coronary arteries but it is limited by blooming artefact caused by the calcification and the lack of distinctive correlation between the sites of the calcification (adventitial, medial, luminal, etc.) on CTCA versus invasive angiography. This can hamper meaningful interpretation for tool of choice to modify the calcified plaque. Also, technology is currently not widely available that would permit co-registration of the CTCA images with the invasive coronary angiography to aid in management of calcified coronary plaque.

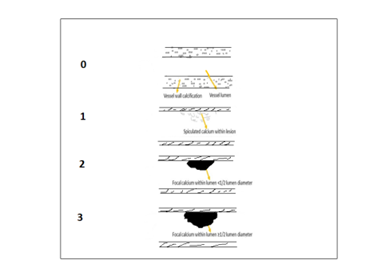

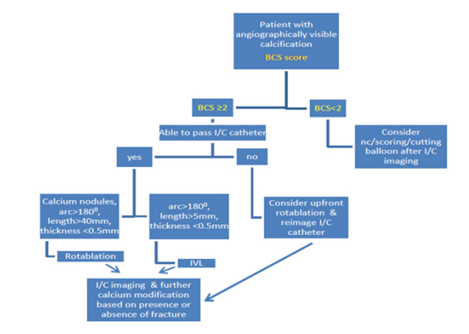

Invasive angiographic calcium assessment has been historically classified as mild, moderate or severe with a moderate degree of correlation noted between angiographic calcification and arc/length of calcium on intracoronary imaging with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) [10]. Recent studies with the IVL balloon have utilized angiographic calcium severity to help guide treatment [11,12]. The authors felt that as this classification can be subjective, a more objective angiographic calcium score was needed. To this end, we developed the Birmingham Calcium Score [BCS] (Figure 1, Table 1), to standardize angiographic calcium assessment and help with choice of calcium modification tools (Figure 2). We have demonstrated strong correlation between this objective angiographic calcification score and the Calcium Volume Index (CVI) [13] score on Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [14] (Table 1). The calcium modification tool choice can be based on both angiographic and intracoronary imaging to assess degree of calcification (Figure 2) [14]. We also demonstrated that patients with BCS 2 or 3 were more likely to require more than one calcium modification tool (example both rotablation and IVL) as compared to those with lesser scores (BCS 0,1) [14].

Intracoronary Imaging

The authors suggest to attempt either an OCT or IVUS catheter prior to choosing a calcium modification tool. The imaging catheter may not pass in cases with excessive calcification with luminal protrusion (BCS 3, Figure 1). This raises the question as to which intracoronary imaging modality is better. IVUS is able to identify the leading edge of calcification but may obstruct visualization of deep calcium in the coronary artery [10,15]. A previous IVUS calcium score which helped to choose calcium modification tools did not incorporate the “reverberation artefact” [16] which was initially identified post-rotablation and is indicative of a thinner calcium layer. Since then, a new IVUS calcification score (scores 0-4) to predict stent expansion in severely calcified coronary lesions has been developed [17] and an adjunctive calcium modification tool is advised when the score is ≥ 2 [17]. This score assesses the arc and length of calcium, presence/absence of calcium nodule and presence/reverberation artefact (Table 1).

Figure 1: Birmingham Calcium Score.

|

Score Name |

Modality |

Range of score |

Details |

Reference |

|

Birmingham Calcium Score (BCS) |

Invasive angiography |

0, 1, 2, 3 |

0: Adventitial calcification 1: Intraluminal speckled calcification 2: Calcium within lumen but<1/2 lumen diameter 3: Calcium within lumen >1/2 lumen diameter |

Figure 1 #14: Sharma et al |

|

Calcium Volume Index (CVI) |

OCT |

0, 1, 2, 3, 4 |

Angle: ≤1800: 0 points >1800: 2 points Thickness: ≤0.5mm: 0 points >0.5mm: 1 point Length: ≤5 mm: 0 points > 5mm: 1 point |

#13: Fujino et al |

|

New IVUS based Calcium Scoring system |

IVUS |

0, 1, 2, 3, 4 |

Length of calcium >2700: ≤5mm: 0 points >5mm: 1 point Vessel diameter: >3.5mm: 0 point ≤3.5mm: 1 point Calcified nodule: Absent: 0 points Present: 1 point Reverberation arc: >900: 0 point ≤900: 1 point |

#17: Zhang et al |

In summary, on IVUS, the presence of a larger artery (vessel diameter ≥ 3.5 mm) and the presence of reverberation artefact >90° indicates that rotablation may not be required and other tools can be utilized for the calcified coronary plaque.

The resolution and accuracy of OCT compared to IVUS is better [15,18,19] and recommended by guidelines [19]. An OCT based calcium score has also been developed called the CVI (as mentioned above) with scores 0-4 [13]. Similar to the IVUS calcium score, this score assesses the arc, length as well as the thickness of calcified coronary plaque. Calcium modification is recommended in lesions whose CVI demonstrates calcium angle >180°, thickness >0.5 mm and length >5 mm and is indicative of stent under expansion.

Calcium modification tools (focus on cutting balloons, rotational atherectomy and IVL)

Cutting balloons: This consists of a non-compliant (nc) balloon catheter with longitudinal surgical blades incorporated on the balloon. Previous cutting balloons were bulky and difficult to deliver. The newer WolverineTM (Boston Scientific Industry Ltd.) cutting balloon is easier to deliver, has better crossability and helps with calcium modification in arteries with minimum tortuosity and short lengths of calcification or the presence of reverberation artefacts [9]. Use of the cutting balloon has demonstrated to improve final stent area with no difference in MACE rates compared to conventional angioplasty [20]. The authors suggest the use of the cutting balloon when superficial calcification is noted on angiography/intracoronary imaging and pre-dilatation balloons pass easily.

Excimer Laser: Excimer laser can be used for modification of fibrotic or moderately calcified coronary plaque; however, it is most frequently used in routine practice for in-stent restenosis (ISR) or for under expanded stents where there is underlying calcific plaque that prevents stent expansion [21]. Another utility of Excimer laser is to create a tract for the rotablation wire in heavily calcified coronary plaque where the rota wire cannot be easily delivered [22].

Rotational Atherectomy (rotablation): This device consists of a diamond coated olive shaped burr rotating at a high speed and causing differential cutting with movement. The device was developed more than 30 years ago and is fairly unchanged since [23]. Rotablation is used as an adjunct in 1-3% of cases to modify calcified coronary plaque [24]. It is a complex intervention device and requires specialized training and experience for safe practice. It also requires a trained team in the cardiac catheterization laboratory to set up and manage the equipment. Complications can occur during the procedure and include burr entrapment, slow or no flow, perforation, AV block, dissection and wire transection [25-27]. High rpms with failure to intermittently “peck” at the calcified lesion is known to generate excessive heat and contribute to thermal injury [28-30].

However, if guidelines and safe practice are adhered to, rotablation can be performed even in the very elderly, as we have demonstrated previously [24], with no increase in complication rate and good safety profile. The authors suggest the use of rotablation when the angiographic calcification score is 2 or 3 and/or intracoronary imaging demonstrates vessel size <3.5 mm with the presence of calcium nodule, calcium arc >270° and long lengths of calcification.

IntraVascular Lithotripsy (IVL): IVL or shockwave is a technology that was initially utilized to treat renal calculi but has since been incorporated onto a balloon for use in calcified coronary lesions. It consists of a single use balloon with two emitters 6 mm apart which convert electrical energy into acoustic pulses in liquid medium. The balloon is programmed to deliver 8 cycles in total with each cycle containing 10 pulses and is available in sizes 2.5 mm-4 mm and a standard length of 12mm [9,11,31]. Although the balloon is bulky, it can be delivered to lesions which demonstrate an under expanded balloon during pre-dilatation. Complications associated with IVL use include perforation, dissection, shocktopics, ventricular ectopy and asynchronous cardiac pacing [11,12,32]. Training for the use IVL is simple and can be easily learnt. The use of IVL is recommended in circumferential calcium with an arc >180° on intracoronary imaging or when non-compliant balloons are distinctly under-expanded on pre-dilatation in the presence of visualized coronary calcification (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Suggested pathway for choice of calcium modification tool.

Conclusion

Increasing longevity translates into an older average cohort of patients presenting to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Older patients have more cardiovascular risk factors and more coronary calcification. Hence it is important that the operators familiarize themselves with the use of calcium modification tools as well as intracoronary imaging. There are several modalities and tools for the treatment of calcified coronary plaque. Both the recognition of the presence of coronary calcification and the ability to utilize more than one tool for calcium modification are necessary for optimal stent expansion, procedural success and good outcomes.

References

2. Jang JJ, Krishnaswami A, Hung YY. Predictive values of Framingham risk and coronary artery calcium scores in the detection of obstructive CAD in patients with normal SPECT. Angiology. 2012;63(4):275-81.

3. Sharma V, Mughal L, Dimitropoulos G, Sheikh A, Griffin M, Moss A, et al. The additive prognostic value of coronary calcium score (CCS) to single photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT-MPI)-real world data from a single center. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019.

4. Lee MS, Shah N. The Impact and Pathophysiologic Consequences of Coronary Artery Calcium Deposition in Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. J Invasive Cardiol. 2016;28(4):160-7.

5. Budoff MJ, Mayrhofer T, Ferencik M, Bittner D, Lee KL, Lu MT, et al. Prognostic Value of Coronary Artery Calcium in the PROMISE Study (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain). Circulation. 2017;136(21):1993-2005.

6. Faggiano P, Dasseni N, Gaibazzi N, Rossi A, Henein M, Pressman G. Cardiac calcification as a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis and predictor of cardiovascular events: A review of the evidence. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(11):1191-204.

7. Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(18):1860-70.

8. Mintz GS. Intravascular imaging of coronary calcification and its clinical implications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(4):461-71.

9. Sheikh AS, Connolly DL, Sharma V. Acute Coronary Syndrome Associated with Calcified Coronary Lesions. Int J Cardiovasc Dis Diagn. 2021; March 23; 6(1): 25-33.

10. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Chuang YC, et al. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995;91(7):1959-65.

11. Ali ZA, Nef H, Escaned J, Werner N, Banning AP, Hill JM, et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Coronary Intravascular Lithotripsy for Treatment of Severely Calcified Coronary Stenoses: The Disrupt CAD II Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(10):e008434.

12. Hill JM, Kereiakes DJ, Shlofmitz RA, Klein AJ, Riley RF, Price MJ, et al. Intravascular Lithotripsy for Treatment of Severely Calcified Coronary Artery Disease: The Disrupt CAD III Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020 Dec 1;76(22):2635-46.

13. Fujino A, Mintz GS, Matsumura M, Lee T, Kim SY, Hoshino M, et al. A new optical coherence tomography-based calcium scoring system to predict stent underexpansion. EuroIntervention. 2018;13(18):e2182-e9.

14. Sharma V, Rahman M, Elangovan SK, Yuan M, O’Kane P, Talwar S, et al. Rotashock Therapy: An Observational Study. J Cardiol Clin Res. 2021; 9(2): 1169.

15. Sharma SK, Vengrenyuk Y, Kini AS. IVUS, OCT, and Coronary Artery Calcification: Is There a Bone of Contention? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):880-2.

16. Kim SS, Yamamoto MH, Maehara A, Sidik N, Koyama K, Berry C, et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of the effects of rotational atherectomy in calcified coronary artery lesions. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34(9):1365-71.

17. Zhang M, Matsumura M, Usui E, Noguchi M, Fujimura T, Fall K, et al. TCT-51 IVUS Predictors of Stent Expansion in Severely Calcified Lesions. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;74(13_Supplement):B51-B.

18. Wang X, Matsumura M, Mintz GS, Lee T, Zhang W, Cao Y, et al. In Vivo Calcium Detection by Comparing Optical Coherence Tomography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):869-79.

19. Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, Johnson TW, Holm NR, Onuma Y, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(35):3281-300.

20. Tang Z, Bai J, Su SP, Wang Y, Liu MH, Bai QC, et al. Cutting-balloon angioplasty before drug-eluting stent implantation for the treatment of severely calcified coronary lesions. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2014;11(1):44-9.

21. Laricchia A, Colombo A. New interventional solutions in calcific coronary atherosclerosis: drill, laser, shock waves. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2020;22(Suppl L):L49-L52.

22. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O'Kane P. Coronary Intervention with the Excimer Laser: Review of the Technology and Outcome Data. Interv Cardiol. 2016;11(1):27-32.

23. Gioia GD, Morisco C, Barbato E. Severely calcified coronary stenoses: novel challenges, old remedy. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2018;14(2):115-6.

24. Sharma V, Abdul F, Haider ST, Din J, Talwar S, O'Kane P, et al. Rotablation in the very elderly - Safer than we think? Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020.

25. Villanueva EV, Wasiak J, Petherick ES. Percutaneous transluminal rotational atherectomy for coronary artery disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(4):CD003334.

26. Chen WH, Lee PY, Wang EP. Left anterior descending artery-to-right ventricle fistula and left ventricular free wall perforation after rotational atherectomy and stent implantation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17(8):450-1.

27. Sakakura K, Ako J, Wada H, Naito R, Funayama H, Arao K, et al. Comparison of frequency of complications with on-label versus off-label use of rotational atherectomy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(4):498-501.

28. Reisman M, Shuman BJ, Dillard D, Fei R, Misser KH, Gordon LS, et al. Analysis of low-speed rotational atherectomy for the reduction of platelet aggregation. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;45(2):208-14.

29. Reisman M, Shuman BJ, Harms V. Analysis of heat generation during rotational atherectomy using different operational techniques. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;44(4):453-5.

30. Tomey MI, Kini AS, Sharma SK. Current status of rotational atherectomy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(4):345-53.

31. De Silva K, Roy J, Webb I, Dworakowski R, Melikian N, Byrne J, et al. A Calcific, Undilatable Stenosis: Lithoplasty, a New Tool in the Box? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(3):304-6.

32. Wilson SJ, Spratt JC, Hill J, Spence MS, Cosgrove C, Jones J, et al. Incidence of "shocktopics" and asynchronous cardiac pacing in patients undergoing coronary intravascular lithotripsy. EuroIntervention. 2020;15(16):1429-35.