Abstract

Objective: The incorporation of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is essential for assessing whether a cancer treatment enhances overall patient well-being, beyond merely extending survival. This scoping review aimed to identify and analyze the use of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials.

Methods: A comprehensive search was conducted in three databases (PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO) to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on ovarian cancer interventions published in peer-reviewed journals. Key study characteristics, including study design, participant demographics, and assessed outcomes, were extracted.

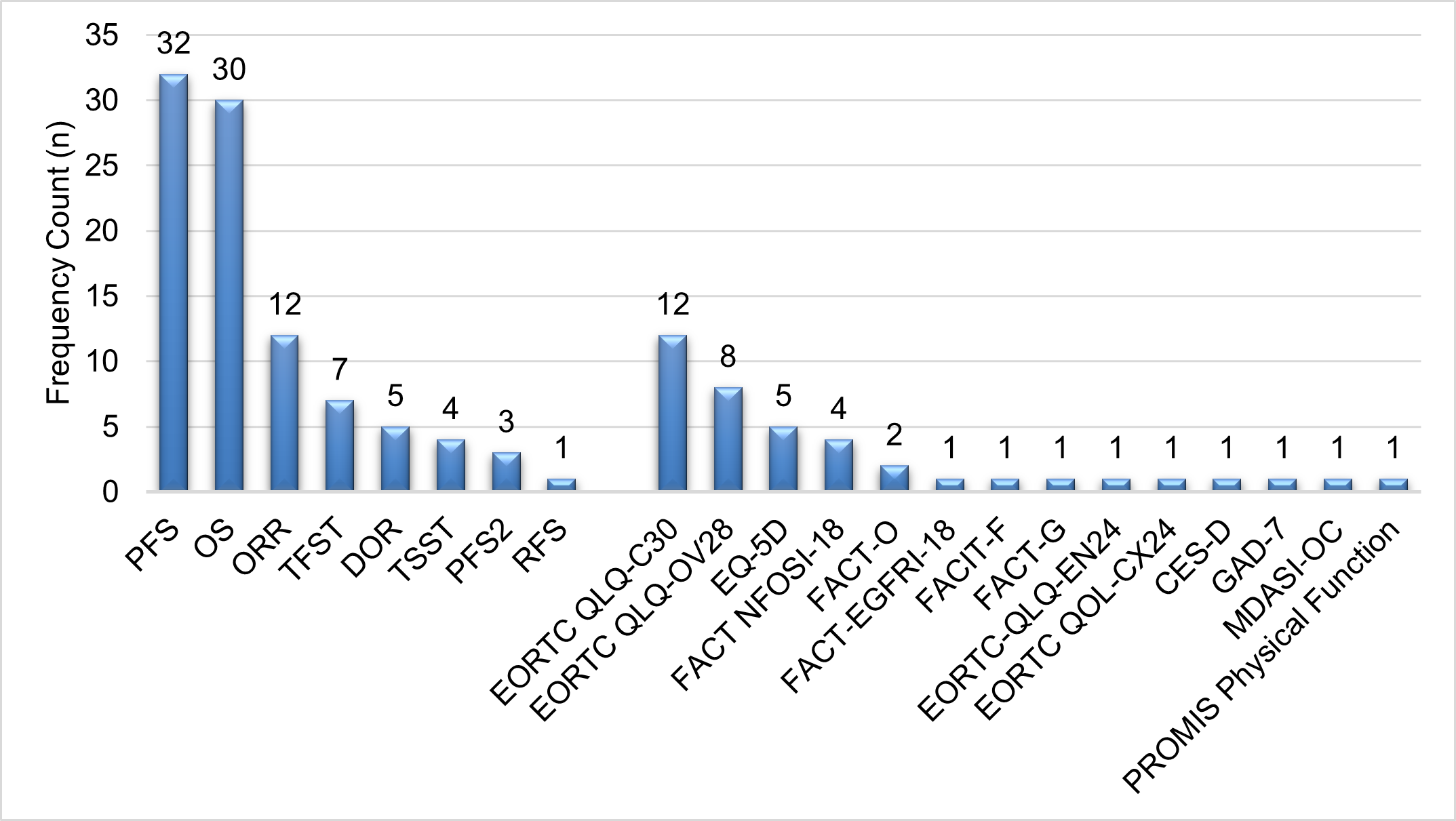

Results: Thirty-six studies were included in the review. The majority reported progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and objective response rate (ORR) as primary and secondary outcomes. Nineteen studies incorporated PROs as outcome measures. The most frequently utilized PRO instruments were the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Ovarian Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-OV28). Other PROs included the EuroQol-5Dimensions (EQ-5D), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors?18 (FACT?EGFRI?18), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian (FACT?O), and NCCN-FACT Ovarian Symptom Index-18 (FACT NFOSI-18). This review summarized the PROs used as assessment endpoints in these trials.

Conclusion: This review highlights the significant yet underutilized role of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials and underscores the need for ovarian cancer-specific PROs to better assess treatment impact on patient quality of life.

Keywords

Ovarian cancer, Ovarian neoplasms, Patient-reported outcome measures, Quality of life, Treatment outcome

Abbreviations

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DOR: Duration of Response; EOC: Epithelial Ovarian Cancer; EORTC-QLQ C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-Core 30; EORTC QLQ-OV28: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Ovarian Cancer Module; EORTC QLQ-EN24: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer - The Endometrial Cancer (EC)-Specific Quality of Life Module; EORTC QOL-CX24: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life (QoL) Questionnaire (QLQ) - The cervical cancer module; EQ-5D: EuroQol-5 Dimensions; FACT?EGFRI?18: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors?18; FACT?O: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian; FACT NFOSI-18: NCCN-FACT Ovarian Symptom Index-18; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Scale; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; HGSOC: High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer; MDASI?OC: MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for Ovarian Cancer; OS: Overall Survival; ORR: Objective Response Rate; PFS: Progression-Free Survival; PFS2: Time to Second Progression or Death; PROMIS Physical Function: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System – Physical Function Scale; RFS: Recurrence-Free Survival; TFST: Time to First Subsequent Therapy; TSST: Time from Randomization to Second Subsequent Therapy or Death.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is a group of diseases that originates in the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum. Globally, ovarian cancer is the eighth most common cancer in women, accounting for an estimated 3.7% of cases and 4.7% of cancer deaths in 2020 [1,2], with 5-year survival rates about 89%, 70%, 36%, and 17% for stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively [3]. Various factors such as older age, hormone replacement therapy, nulliparity, anthropometric indices, physical activity, and dietary intake affect the occurrence of ovarian cancer, from which a family history of the disease, genetic factor, are among the most important ones [4-6]. It has been reported that first-degree relatives of probands have a 3- to 7-fold increased risk [7,8].

Symptoms associated with ovarian cancer often include abdominal bloating, fullness, and pressure in the abdomen, abdominal pain, back pain, urinary urgency/frequency, constipation, or difficulty eating [9-14]. In addition to the discomfort caused by surgery or combination chemotherapy, ovarian cancer may significantly impact the quality of life for individuals in several ways. Severe abdominal and pelvic pain can be particularly challenging for patients [15]. The treatments for ovarian cancer, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, frequently lead to extreme fatigue, which affects daily activities and reduces overall energy levels [16].

Moreover, reduced appetite and digestive issues can result in nutritional deficiencies and weight loss [17,18]. Chemotherapy and radiation may cause side effects such as nausea, vomiting, hair loss, and increased susceptibility to infections, further compromising physical well-being [19,20]. Mental health is also adversely affected, with many patients experiencing anxiety, depression, stress, and concerns about body image [21]. These physical symptoms and emotional strains often lead to social withdrawal and isolation, reducing interaction with friends and family [22]. The need for frequent medical appointments and the physical inability to work can result in loss of income, adding to financial stress [23].The cumulative effect of these physical, emotional, social, and financial challenges can significantly reduce the overall quality of life for individuals with ovarian cancer.

Various context-specific patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and PRO endpoints have been utilized in clinical trials for ovarian cancer [24]. The incorporation of PROs is essential for assessing whether a treatment enhances overall patient well-being, beyond merely extending survival. PROs offer valuable insights into patients' perspectives on treatment effectiveness and tolerability, thereby aligning with the principles of patient-centered care. Moreover, the use of PROs contributes to improving the quality of care by adopting a more patient-centered approach.

This scoping review aimed to identify and analyze the use of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials. The objectives of this scoping review were: (a) to examine the use of PROs as assessment endpoints in ovarian cancer clinical trials; (b) to identify and rank the most frequently utilized PROs as assessment endpoints in these trials; and (c) to provide a detailed description of the most commonly used PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials.

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy for this scoping review was developed and executed by two reviewers in collaboration with a professional librarian, ensuring a comprehensive and systematic approach. The following online databases were searched: PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. To capture a broad range of studies, a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword search terms was utilized. The search terms included: "ovarian cancer*" OR "Ovarian Neoplasms*" OR "Cystadenocarcinoma, Serous"[MeSH] OR "Cystadenocarcinoma, Mucinous"[MeSH] OR "Epithelial Ovarian"[MeSH]; ("ovarian cancer"[Title]) AND (("ovarian cancer*" OR "Ovarian Neoplasms*" OR "Cystadenocarcinoma, Serous"[MeSH] OR "Cystadenocarcinoma, Mucinous"[MeSH] OR "Epithelial Ovarian"[MeSH]) AND ("randomized controlled trial" OR "RCT" OR "clinical trial")). Additionally, the search strategy incorporated title-specific searches, such as "ovarian cancer"[Title].

Study eligibility

Titles and abstracts were screened based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles; (2) Phase II or III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) focused on cancer interventions; (3) involvement of human subjects diagnosed with ovarian cancer; (4) reporting on outcome measures used in ovarian cancer research; (5) a quality study design with a PEDro scale score of ≥ 6; and (6) publication in English. The outcome measures considered included, but were not limited to, disease progression, treatment response, quality of life, survival rates, and adverse events. Only studies published between January 2023 and July 2024 were included to ensure relevance to current practices. Our decision to include only Phase II and III RCTs was guided by the need to focus on studies that provide robust evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of cancer interventions. During the search process, we also found limited publications in Phase I and Phase IV related to ovarian cancer clinical treatment. The decision to limit our review to studies published in 2023 to 2024 was made to ensure that the evidence considered is current and reflective of the latest advancements in ovarian cancer research and treatment. The PEDro scale was chosen for assessing the quality of the RCTs included in our review due to its established reliability and validity in evaluating methodological quality. As a rule of thumb, total PEDro scores of 0-3 are considered 'poor', 4-5 'fair', 6-8 'good', and 9-10 'excellent.' We set a threshold score of ≥ 6 on the PEDro scale to ensure that only studies with a high level of methodological rigor were included.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were non-peer-reviewed articles, such as conference abstracts, letters, editorials, and commentaries; (2) were animal studies; (3) involved secondary data analysis; (4) focused on diet, physical activity interventions, app-based digital therapeutic interventions, health coaching, or genetic counseling; and (5) did not report on outcome measures relevant to ovarian cancer research.

Quality assessment

To ensure the quality of the included randomized, controlled trials, researchers evaluated studies using the PEDro scale with classifications of “poor” (scores 0–3), “fair” (4–5), “good” (6–8), and “excellent” (9–10) [25,26].

Data extraction

A comprehensive data extraction form was developed to systematically gather relevant information from the included studies. The form collected the following details: (a) the first author and publication year; (b) the time of publication; (c) the study design; (d) the characteristics of the participants, including sample size and diagnosis; (e) the details of the experimental and control interventions; and (f) the outcome measures reported.

Data synthesis

We conducted a descriptive frequency count and calculated the percentages to examine the use of PROs as assessment endpoints in ovarian cancer clinical trials. We also identified and ranked the most frequently utilized PROs in these trials. Additionally, we provided a description of the most used PROs, offering insights into their application, psychometric properties, and relevance in ovarian cancer research.

Results

Search results

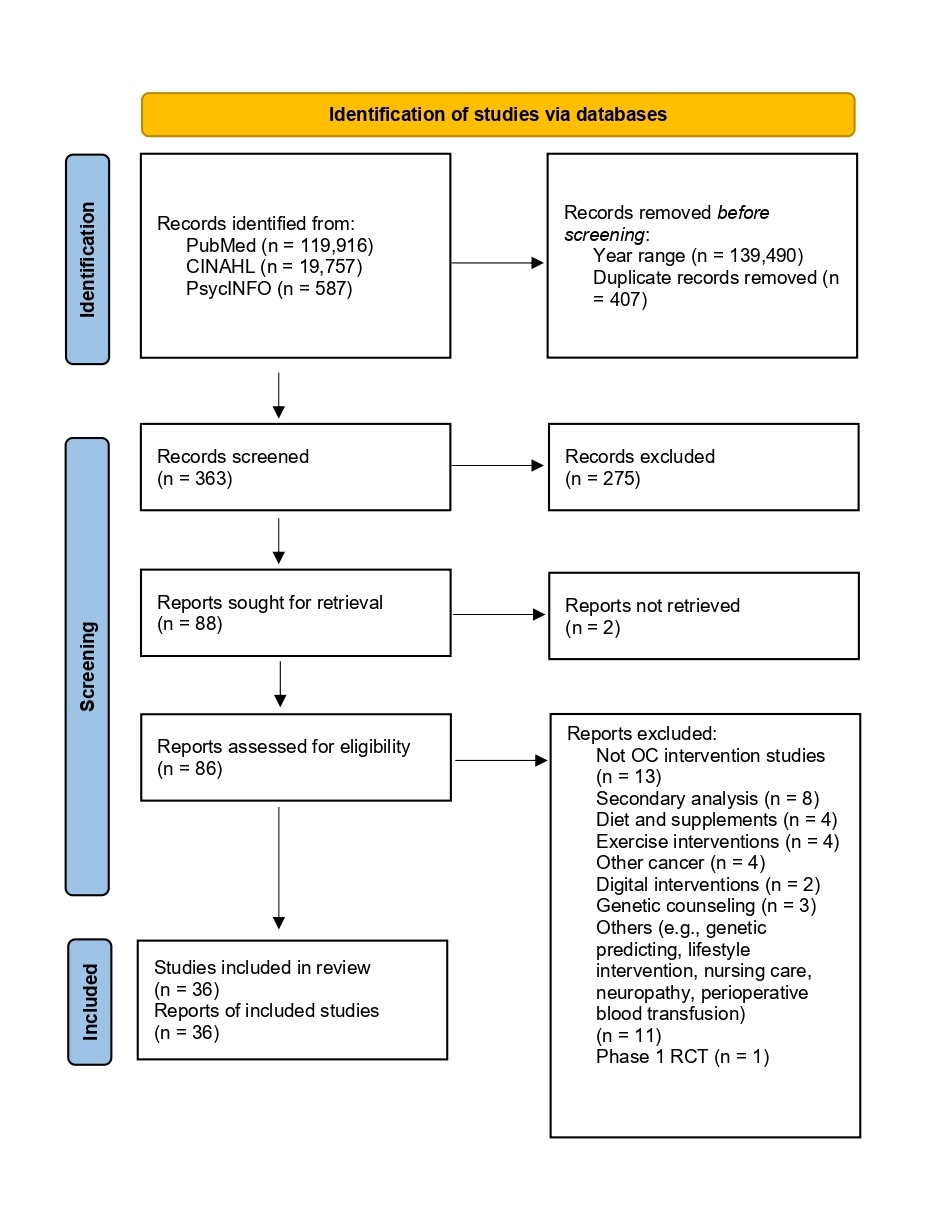

Our literature search identified 88 records, with 36 (41%) being RCTs that met our study's inclusion criteria. The excluded studies did not pertain to ovarian cancer interventions or were secondary data analyses. Other excluded interventions focused on diet and supplements, physical activity, app-based digital therapy, lifestyle changes, neuropathy, nursing care, pre-visit online information tools, self-efficacy, surgical procedures, perioperative blood transfusions, genetic counseling, and genetic prediction. Among the included studies, 25 were published in 2023 and 11 in 2024. Thirteen studies were phase 2 trials, while 23 were phase 3 trials. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the search results.

The use of PROs as assessment endpoints

Table 1 summarizes the included studies in ovarian cancer trials. Of the 36 studies, most reported progression-free survival (PFS) (n = 32), overall survival (OS) (n = 30), and objective response rate (ORR) (n = 12) (according to RECIST version 1.1) as primary and secondary outcome measures to evaluate treatment effects. Other secondary outcome measures included duration of response (DOR), time to first subsequent therapy (TFST), time from randomization to second subsequent therapy or death (TSST), and time to second progression or death (PFS2).

|

# |

Author |

Year |

Study Phase |

Study Design |

Participant Diagnosis |

Experimental Group (n) |

Control Group (n) |

Outcome Measures / Endpoints |

|

1 |

Mutch |

2024 |

Phase 2 |

Open?label, two-arm, randomized, phase 1b clinical study + Stage 2 randomized dose expansion phase |

Patients with BRCA wild?type platinum-sensitive, recurrent, ovarian cancer (PSROC) (phase 2). |

Cobimetinib + Niraparib (n = 39) |

Cobimetinib + Niraparib + |

PFS |

|

2 |

Lorusso |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

Prospective, open-label, randomized phase III MITO-23 trial |

Patients with BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers or patients with BRCAness phenotype with recurrent OC, primary peritoneal carcinoma, or fallopian tube cancer |

Trabectedin 1.3 mg/m2 (n = 122) |

Physician's choice chemotherapy (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, topotecan, gemcitabine, once-weekly paclitaxel, or carboplatin) (n = 122) |

PFS |

|

3 |

Rimel |

2024 |

Phase 2 |

Open?label, randomized, 3-arm phase II trial |

Patients with recurrent or persistent endometrial cancer (EC); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 0-2 |

(1) Cediranib (n = 40); (2) Olaparib (n = 40) |

Olaparib + cediranib (n = 40) |

PFS |

|

4 |

Ganz |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

Randomized, double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled, multi-center phase III study |

Patients with germline BRCA1/2 |

Olaparib (n = 361) |

Placebo (n = 407) |

EORTC QLQ-C30 |

|

5 |

Konstantinopoulos |

2024 |

Phase 2 |

A multicenter, open-label, randomized phase 2 |

Patients with platinum-resistant HGSOC |

Gemcitabine plus berzosertib (n = 34) |

Gemcitabine-alone (n = 36) |

PFS |

|

6 |

Lorusso |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

Randomized, double-blind, |

Patients with newly diagnosed FIGO stage III or IV, high-grade serous or high-grade endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal and/or fallopian tube cancer, or other epithelial non-mucinous ovarian cancer with a germline BRCA mutation |

Olaparib + bevacizumab (n = 144) |

Placebo + Olaparib + |

PFS |

|

7 |

Hinchcliff |

2024 |

Phase 2 |

An open?label, adaptively randomized open?label trial |

Patients with HGSOC platinum?resistant or refractory disease |

Sequential arm (tremelimumab followed by durvalumab) (n = 38) |

Combination arm (tremelimumab + durvalumab, followed by durvalumab monotherapy) (n = 23) |

PFS |

|

8 |

Nicum |

2024 |

Phase 2 |

An academic, randomized Phase II trial, |

Patients with relapsed ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer |

(1) Paclitaxel (n = 46); (2) Olaparib (n = 46) |

Olaparib + cediranib (n = 47) |

PFS |

|

9 |

Campos |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

A single-center, randomized phase 3 clinical trial |

Patients with peritoneal involvement of primary EOC (FIGO stages II, III, and IV) or tumor recurrence |

HIPEC arm: cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with paclitaxel (n = 41) |

Non-HIPEC arm: cytoreductive surgery |

RFS |

|

10 |

Arend |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

An international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial conducted at 86 sites |

Patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory EOC (including primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers) |

Ofra-vec + paclitaxel (n = 203) |

Placebo + paclitaxel (n = 202) |

PFS |

|

11 |

Chen |

2024 |

Phase 3 |

A prospective, randomized, case-control trial |

Patients with diagnosis of recurrent EOC, peritoneal cancer, or fallopian tube cancer within three lines |

Secondary cytoreductive surgery (SCS) followed by non-platinum single agent chemotherapy (paclitaxel, gemcitabine or liposomal adriamycin) (n = 70) |

Non-platinum single agent chemotherapy alone (n = 70) |

PFS |

|

12 |

Vergote |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study at 107 sites in 10 countries |

Patients with diagnosis of endometrial cancer (EC) of the endometrioid, serous or undifferentiated type, or uterine carcinosarcoma. |

Selinexor |

Placebo |

PFS |

|

13 |

Moore |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A phase 3, global, confirmatory, open-label, randomized, controlled trial |

Patients with platinum resistant, high-grade serous ovarian cancer. |

Mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx (MIRV) (n = 227) |

Chemotherapy (n = 226) |

PFS |

|

14 |

Marchetti |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

An open-label, randomized, phase-III |

Patients with stage-IIIC/IV EOC and high tumor load. |

Primary debulking surgery (PDS) (n = 84) |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by interval debulking surgery (IDS) (NACT/IDS) (n = 87) |

PFS |

|

15 |

Pujade-Lauraine |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase IIIb trial. |

Patients with non-mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer, primary peritoneal cancer, and/or fallopian tube cancer. |

Olaparib (n = 74) |

Placebo (n = 38) |

PFS |

|

16 |

Kurtz |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A placebo-controlled double-blinded randomized phase III trial |

Patients with recurrent epithelial OC, one to two previous chemotherapy lines, and platinum-free interval (PFI) >6 months |

Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab (n = 491) |

Placebo (n = 186) |

PFS |

|

17 |

Colombo |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A three-arm randomized, controlled, open-label, phase II study |

Patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant/refractory, high-grade serous or endometrioid epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer, or ovarian carcinosarcoma |

(1) nab-paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 + relacorilant 150 mg orally (n = 60); (2) nab-paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 + relacorilant 100 mg orally (n = 57) |

nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 (n = 60) |

PFS |

|

18 |

Pignata |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled |

Patients with untreated FIGO stage III or IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer |

Atezolizumab + carboplatin/ |

Placebo + carboplatin/ |

PFS |

|

19 |

Aronson |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

An open-label, randomized, controlled, phase III trial |

Patients with primary epithelial stage III ovarian cancer |

Interval cytoreductive surgery without HIPEC (surgery group) |

HIPEC (100 mg/m2 cisplatin; surgery-plus-HIPEC group). |

PFS |

|

20 |

Holloway |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A multicenter, prospective, randomized, and active-controlled phase III trial. |

Patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant/refractory, non-resectable high-grade serous, endometrioid, or clear-cell ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer |

Olvimulogene nanivacirepvec (Olvi-Vec) + platinum-based chemotherapy (n = 124) |

Bevacizumab (n = 62) |

PFS |

|

21 |

Li |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study |

Patients with newly diagnosed advanced OC who received primary or interval debulking surgery and responded to treatment with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy |

Niraparib (n = 255) |

Placebo (n = 129) |

PFS |

|

22 |

Peipert |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, double-blind, |

Patients with platinum-sensitive, high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube carcinoma |

Rucaparib (n = 375) |

Placebo (n = 189) |

FACT NFOSI-18 |

|

23 |

González-Martín |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study |

Patients with advanced (FIGO stage III/IV), high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer |

Niraparib (n = 487) |

Placebo (n = 246) |

PFS |

|

24 |

Dorigo |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A multicenter, randomized, open-label, single-arm phase II study |

Patients with stage IIc–IV, recurrent, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer |

maveropepimut-S with cyclophosphamide (n = 22) |

n/a |

ORR |

|

25 |

Ray-Coquard |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial conducted in 11 countries |

Patients with advanced stage (FIGO stage III or IV) high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian cancer |

Olaparib plus bevacizumab |

Placebo plus bevacizumab |

PFS |

|

26 |

Vergote |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A double-blind phase II randomized study |

Patients with recurrent or primary advanced (FIGO stage IVB) cervical cancer. |

Nintedanib (n = 62) |

Placebo (n = 58) |

PFS |

|

27 |

Mirza |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial |

Patients with advanced cancer of the ovary, peritoneum, or fallopian tube (collectively defined as ovarian cancer). |

Niraparib (n = 484) |

Placebo (n = 246) |

PFS |

|

28 |

Banerjee |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter randomized clinical trial |

Patients with ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal origin with relapse in the platinum-resistant or refractory time frame |

Paclitaxel plus vistusertib (n = 70) |

Paclitaxel plus placebo (n = 70) |

PFS |

|

29 |

Praiss |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

An investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, randomized phase II study |

Patients with first recurrence of high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer |

Secondary cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC |

Secondary cytoreductive surgery |

PFS |

|

30 |

Colombo |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

An open-label, international, parallel-group, randomized phase III trial conducted at 117 centers in 11 European countries |

Patients with epithelial ovarian, epithelial fallopian tube cancer or primary peritoneal cancer |

carboplatin and pegylated liposomal |

Trabectedin and pegylated liposomal |

PFS |

|

31 |

Herzog |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A global, multicenter, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled phase II study |

Patients with high-grade serous epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer following first relapse |

(1) farletuzumab + carboplatin/pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (FAR + CARBO/PLD) (n = 106); (2) farletuzumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel (FAR + CARBO/PTX) (n = 36) |

Placebo + carboplatin/pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLB + CARBO/PLD) (n = 52); placebo + farletuzumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel (PLB + CARBO/PTX) (n = 20) |

PFS |

|

32 |

Ferron |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized phase II trial |

Patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer |

Nintedanib (n = 123) |

Placebo (n = 61) |

PFS |

|

33 |

Pfisterer |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III trial |

Patients with FIGO stage IIB-IV epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer |

Bevacizumab (for 15 months) (n = 450) |

Bevacizumab (for 30 months) (n = 450) |

PFS |

|

34 |

DiSilvestro |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, international, phase III SOLO1/GOG 3004 study |

Patients with FIGO stage III disease had undergone an attempt at optimal upfront or interval cytoreductive surgery |

Olaparib (n = 260) |

Placebo (n = 131) |

PFS |

|

35 |

Mizuno |

2023 |

Phase 3 |

An international, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial |

Patients with previously untreated stage III or IV high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma |

(1) veliparib-throughout (veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel and veliparib maintenance) (n = 382) (2) veliparib-combination-only (veliparib with carboplatin/ |

Control (placebo with carboplatin/paclitaxel and placebo maintenance) (n = 375) |

PFS |

|

36 |

Crabb |

2023 |

Phase 2 |

A Randomized, double-Blind, biomarker-selected, phase II clinical trial |

Patients with stage IV (stage T4b and/or N1-3 and/or M1), histologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma unsuitable for curative treatment options |

Rucaparib (n = 20) |

Placebo (n = 20) |

PFS |

Nineteen of the 36 studies reported using PROs as part of their outcome measures. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Ovarian Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-OV28) were the most used PROs, reported by 12 and 8 studies, respectively. Additionally, 5 studies used the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), either the 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) or 3-level (EQ-5D-3L) versions, and 4 studies used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors-18 (FACT-EGFRI-18). Figure 2 presents the ranked utilization of the assessment endpoints in ovarian cancer clinical trials.

Figure 2: Utilization of the assessment endpoints in ovarian cancer clinical trials (n = 36 studies).

Abbreviations: PFS: Progression-Free Survival; OS: Overall Survival; ORR: Objective Response Rate; TFST: Time to First Subsequent Therapy; DOR: Duration of Response; RFS: Recurrence-Free Survival; TSST: Time from Randomization to second Subsequent Therapy or Death; PFS2: Time to Second Progression or Death; EORTC-QLQ C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-Core 30; EORTC QLQ-OV28: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Ovarian Cancer Module; EQ-5D: EuroQol-5Dimensions; FACT?EGFRI?18: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors?18; FACT?O: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian; FACT NFOSI-18: NCCN-FACT Ovarian Symptom Index-18; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Scale; MDASI?OC: MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for Ovarian Cancer; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; EORTC QLQ-EN24: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer - The Endometrial Cancer (EC)-specific Quality of Life Module; EORTC QOL-CX24: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life (QoL) Questionnaire (QLQ) - The Cervical Cancer Module; PROMIS Physical Function: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System – Physical Function Scale

EORTC-QLQ-C30

History: Founded in 1962, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) is an international non-profit organization dedicated to conducting, developing, coordinating, and promoting cancer research in Europe through multidisciplinary groups of oncologists and scientists. In 1987, the EORTC introduced its first core questionnaire, the 36-item EORTC QLQ-C36. This was followed by several versions of the 30-item QLQ-C30 (versions 1.0 [27], 2.0 [28], and 3.0) [29], with version 3.0 currently being the standard. This version takes approximately 13 minutes to complete [30].

Description: The EORTC-QLQ-C30 is widely used to evaluate the quality of life of cancer patients in international clinical trials and research [31,32]. The questionnaire includes 30 items, incorporating functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), symptom scales (fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting), global health status/quality of life scales, and single items assessing additional symptoms (dyspnea, appetite loss, insomnia, constipation, diarrhea). Example questions are “Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or a suitcase?”, “Were you tired?”, and “Have you felt nauseated?”

Rating Scale: Most items use a 4-point Likert scale (1=“Not at all”, 4=“Very much”), while overall health and quality of life items use a 7-point scale (1=“Very poor”, 7=“Excellent”). Scores are calculated by averaging the responses within each scale and then linearly transforming these averages to a 0-100 scale. Higher scores on functional scales and global quality of life indicate better functioning, whereas higher scores on symptom scales indicate greater symptom burden.

Reliability and Validity: The EORTC QLQ-C30 has been validated in numerous languages and cultural contexts, making it a reliable and internationally recognized tool for use in clinical and epidemiological cancer research. Studies have shown that the EORTC QLQ-C30 is adequately valid [28,30,33-41] and reliable [28,30,33-39,41-43], with reported Cronbach's alpha values for internal consistency ranging from >0.70 to 0.97 [28,30,34-37,44]. Factor analyses suggest different models: a four-factor model by Jassim (2020) [33], a six-factor solution by Kyriaki (2001) [41], and a nine-dimensional structure by Shin et al. (2018) [40] using the Rasch model.

Convergent and discriminant validity have been supported through correlations with other assessments, such as the EORTC QLQ-BR23 (Breast Cancer module) [34], 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [35,44], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [38].

Responsiveness: Studies report the responsiveness index of the EORTC QLQ-C30 [45,45-49]. Osoba (1998) [49] noted mean score changes of 5-10 points for "a little" change; 10-20 points for "moderate" change; and over 20 points for "very much" change. Musoro (2019) [46] reported the minimally important difference (MID) for within-group change as 5-14 points, and for between-group change over time as 4-11 points. Recently, publications providing guidance on minimal clinically important differences (MCID) for the QLQ-C30 displayed a growing trend away from broad legacy thresholds of 10 points for all QLQ-C30 scales, toward deriving contemporary thresholds (e.g., QLQ-C30 subscales) [48,50]. Clarke et al. (2024) [32] provided a comprehensive review of meaningful change thresholds (i.e., MCID) by subscales. Giesinger (2016) [47] reported thresholds for clinical importance (TCI) of 83, 70, 39, and 25 for physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue, and pain subscale, respectively.

EORTC QLQ-OV28

History: The EORTC QLQ-C30 (core questionnaire) can be supplemented with disease-specific modules. The development process is divided into four phases, where Phases I and II are in early stage and Phase III is pre-testing process, and Phase IV is to make modules available for use. For example, EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL is a shortened version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 meant for palliative cancer care patients. EORTC QLQ-F17 is a shorter, 17-item version that includes only the functional scales and the global health status/quality of life scale of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Other modules include (but not limited to) QLQ- BN20 (brain tumor), QLQ-BR45 (45-item) and QLQ-BR23 (23-item) (breast cancer), QLQ-EN24 (endometrial cancer), QLQ-FERT45 and FERT29 (fertility module), QLQ-HCPS73 (hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome), and QLQ-pNET (pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor), QLQ-SBQ (symptom-based questionnaire), QLQ-AYA (adolescents and young adults), QLQ-CX24 (cervical cancer), QLQ-ELD14 (elderly), QLQ-H&N35 (head and neck), QLQ-LMC21 (colorectal liver metastases), QLQ-BM22 (bone metastases), QLQ-OG25 (esophagi-gastric cancer), QLQ-CR29 (colorectal cancer), QLQ-OPT30 (uveal melanoma).

Scale: The EORTC QLQ-OV28 [51-54] is a specialized instrument designed to assess the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer. The EORTC QLQ-OV28 is composed of 28 items, incorporating questions assessing abdominal/gastrointestinal symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, chemotherapy side effects, hormonal/menopausal symptoms, body image, attitude to disease, sexual functioning, pain, impact of disease/treatment on daily activities. All items use a 4-point Likert scale (1=“Not at all”, 4=“Very much”). Example questions are “Did you have abdominal pain?”, “Did you have a bloated feeling in your abdomen / stomach?”, and “Did you urinate frequently?” Studies supported that Questionnaires were well accepted by patients [54], with Cronbach's α coefficients >0.7 (range, 0.57?0.86) [51], test-retest reliability (Spearman's rho) was 0.84 [53].

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D questionnaire [55], developed by the EuroQol Group, is a standardized instrument used to measure health-related quality of life. Their development raised translation and semantic issues, experience with which helped feed into the design of three instruments, the EQ-5D-3L (three-level version), EQ-5D-5L (five-level version), and EQ-5D-Y (youth), as part of the EuroQol portfolio. The EQ-5D includes five dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.

FACT-G, FACT?O, FACT NFOSI-18, FACIT-F, FACT-EGFRI-18

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) group is a collaborative organization that focuses on developing and validating questionnaires that assess the impact of chronic illnesses on patients' quality of life. All these questionnaires use a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Not at all”, 4 = “Very much”).

Functional assessment of cancer therapy - general (FACT-G) [56,57]: This 27-item questionnaire includes the FACT-G core dimensions: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, and functional well-being.

Functional assessment of cancer therapy - ovarian (FACT-O) [58]: This 39-item questionnaire is designed to provide a comprehensive measure of quality of life for ovarian cancer patients. It combines the FACT-G core dimensions with an ovarian cancer-specific subscale. Example questions include, “I have swelling in my stomach area,” “I like the appearance of my body,” and “I have concerns about my ability to have children.”

National comprehensive cancer network/functional assessment of cancer therapy ovarian cancer symptom index (FACT NFOSI-18) [59]: Developed by a collaboration between the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the FACIT group, this 18-item questionnaire is designed for ovarian cancer patients. It focuses on assessing ovarian cancer-specific symptoms, such as energy, pain, feeling ill, cramps in the stomach area, fatigue, constipation, sleep, nausea, hair loss, vomiting, and skin problems.

Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy - fatigue (FACIT-F) [60,61]: This scale measures the level of fatigue experienced by patients and its impact on their daily functioning and overall quality of life. Example questions include, “I feel fatigued,” “I feel listless (‘washed out’),” and “I am frustrated by being too tired to do the things I want to do.”

FACT-EGFRI-18 [62]: This 18-item questionnaire is designed to assess the impact of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors (EGFRIs) on the quality of life of cancer patients. It measures the severity and impact of symptoms associated with EGFRI treatment and assesses how these symptoms affect patients' overall quality of life and daily functioning. Example questions include, “My skin or scalp feels irritated” and “My skin condition interferes with my social life.”

Discussion

The scoping review aimed to evaluate the integration of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials to assess their impact on patient well-being beyond survival metrics. Of the 36 trials reviewed, most focused on PFS, OS, and ORR. However, only 19 trials reported incorporating PROs. The most frequently used PRO instruments were the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-OV28, with additional PROs including the EQ-5D, FACT-EGFRI-18, FACT-O, FACT NFOSI-18, and FACT-F.

In the past few years, federal policies and initiatives increasingly recognize the value of PROs in assessing the quality and effectiveness of care, influencing health policy and reimbursement strategies. Agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have issued guidance on incorporating PROs into clinical trials and value-based care models. Furthermore, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fund research that includes PROs to ensure that patient perspectives are considered in evaluating healthcare interventions. Reliable, valid, and responsive PROs can assist clinicians in understanding patient experiences, preferences, and needs, thereby leading to more personalized treatment plans. They also help in tracking symptoms, side effects, and overall health status over time and facilitate meaningful discussions between patients and healthcare providers.

In a cross-sectional, descriptive survey study, Pozzar et al. (2021) [63] found that greater patient-centered communication is significantly associated with improved quality of life and reduced symptom burden in individuals with ovarian cancer. Similarly, Campbell (2019) [24] and Hilpert et al. (2021) [64] highlighted the value of PROs in guiding treatment decisions in ovarian treatment. The inclusion of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials underscores the importance of assessing the holistic impact of treatments, extending beyond traditional endpoints like survival rates. This approach enables clinicians to make treatment decisions that not only extend life but also enhance patient quality of life. The use of validated PRO instruments, such as the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and FACT-O, provides a robust framework for evaluating multiple dimensions of patient well-being, including physical, emotional, and social aspects. However, there remains a need for reliable, valid, and sensitive-to-change PRO instruments that are specifically tailored to ovarian cancer patients. Such tools would better capture the unique challenges faced by this population, improving the relevance of clinical trial outcomes.

This study identified the underutilization of PRO measures in ovarian clinical trials. Although PROs are valuable for capturing patients' perspectives on their health, quality of life, and treatment effects, their application in phase II or phase III oncology RCTs can be attributed to several challenges. First, incorporating PROs requires careful planning to select appropriate instruments. Second, collecting and analyzing PRO data requires additional resources, including time, funding, and manpower. Third, the primary focus in cancer trials is often on hard clinical endpoints, such as survival rates, tumor response, or disease progression. Fourth, administering PRO surveys can increase the burden on patients, particularly in trials where patients already undergo extensive testing or treatment. Beyond the availability of reliable, valid, and sensitive PRO measures, there is a need for efficient data collection methods that minimize patient burden. For example, Kennedy (2022) [65] explored the experiences and acceptability of an electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) pathway among both ovarian cancer patients and clinicians during follow-up care.

Among both generic and disease-specific PRO measures, the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-OV28 were the most frequently used in ovarian cancer RCTs. While previous studies have validated the psychometric properties of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 and supported its use across various cancer types, it is important to note that these validations primarily involved patients with breast cancer [37,43], lung cancer [36,38], multiple myeloma [44], and diverse cancer patients [33-35,39,40], rather than specifically ovarian cancer. Therefore, future research is needed to validate the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in ovarian cancer patients across different stages of the disease.

For PROs to be clinically useful in evaluating the success and meaningfulness of interventions, accurate interpretation of score changes, including cut-off scores and MCIDs, is crucial. A key concern is the wide variability in MCID estimates across subscales, ranging from 5 to 30 points, the inclusion of both improvement and deterioration thresholds, and this variability is evident in the substantial differences reported in MCID estimates across various studies. For example, Raman (2018) [48] reported the MCIDs of 5.2 (physical), 11.9 (role), 8.1 (emotional), 8.4 (social), -13.3 (fatigue), -9.4 (pain), -4.0 (nausea and vomiting), and -9.4 (appetite). Maringwa (2011) [45] provided MCID estimates: physical (5.6 points), role (14.3), and cognitive functioning (7.6); global health status (7.3), fatigue (-12.4), and motor dysfunction (-4.3). Zeng (2012) [50] reported MCIDs as: physical (8.0), role (5.8), emotional (13.4), cognitive (12.6), social (16.8), global health status (4.6), fatigue (-11.4), pain (-30.5), dyspnea (-2.2), insomnia (-21.9), appetite (-22.8), financial problem (-11.2). Future research is needed to establish consistent and meaningful change thresholds to accurately identify responders in ovarian cancer clinical trials.

This study has several limitations. First, the review was based on data extracted from published articles, which may not have disclosed all instances of PROs use, even if PROs were included in the research protocols. As a result, the actual frequency of PRO utilization might be underestimated. Additionally, there may be duplication of data if multiple studies report on the same research or clinical trials. Identifying and addressing this overlap can be challenging. Despite our efforts to identify and address such overlaps, there remains a risk that PRO utilization may be reported more than once if studies stem from the same trial. These factors could affect the accuracy of our findings regarding the prevalence and application of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials. By restricting our review to publications from January 2023 to July 2024, we missed the opportunity to examine trends over a longer period. An extended review covering the past five years, for instance, could have provided insights into the utilization trends of PROs in ovarian cancer trials, offering a more comprehensive view of how these measures have been adopted over time. Lastly, the review study is inevitably susceptible to publication bias. By limiting the inclusion to articles published in English, studies published in other languages are excluded. Additionally, studies with statistically significant or positive results are more likely to be published in peer-reviewed journals. Restricting the review to Phase II or III RCTs may exclude valuable data from quasi-experimental or observational studies that could provide additional insights into outcome measures used in ovarian cancer research.

Conclusion

This review underscores the critical yet underutilized role of PROs in ovarian cancer clinical trials and emphasizes the need for ongoing efforts in the development and validation of ovarian cancer-specific PRO instruments. Such advancements are essential for more accurately assessing the effects of treatments on patients' well-being and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

None. Financial support was not received. Copyrighted material was not used. Copyrighted surveys/instruments/tools were not used.

References

2. Webb PM, Jordan SJ. Epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017 May;41:3-14.

3. Baldwin LA, Huang B, Miller RW, Tucker T, Goodrich ST, Podzielinski I, et al. Ten-year relative survival for epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;120(3):612-8.

4. Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:287-99.

5. Ali AT, Al-Ani O, Al-Ani F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Przeglad Menopauzalny Menopause Rev. 2023 Jun;22(2):93-104.

6. Whelan E, Kalliala I, Semertzidou A, Raglan O, Bowden S, Kechagias K, et al. Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer: An Umbrella Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2022 May 30;14(11):2708.

7. Parazzini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Restelli C, Franceschi S. Family history of reproductive cancers and ovarian cancer risk: an Italian case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Jan 1;135(1):35-40.

8. Sutcliffe S, Pharoah PD, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Ovarian and breast cancer risks to women in families with two or more cases of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000 Jul 1;87(1):110-7.

9. Goff B. Symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;55(1):36-42.

10. Olson SH, Mignone L, Nakraseive C, Caputo TA, Barakat RR, Harlap S. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Aug;98(2):212-7.

11. Ebell MH, Culp MB, Radke TJ. A Systematic Review of Symptoms for the Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar;50(3):384-94.

12. Chan JK, Tian C, Kesterson JP, Monk BJ, Kapp DS, Davidson B, et al. Symptoms of Women With High-Risk Early-Stage Ovarian Cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Feb 1;139(2):157-62.

13. Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):221-7.

14. Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004 Jun 9;291(22):2705-12.

15. Gilbertson-White S, Campbell G, Ward S, Sherwood P, Donovan H. Coping With Pain Severity, Distress, and Consequences in Women With Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(2):117-23.

16. Hagan TL, Arida JA, Hughes SH, Donovan HS. Creating Individualized Symptom Management Goals and Strategies for Cancer-Related Fatigue for Patients With Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(4):305-13.

17. Rietveld MJA, Husson O, Vos MC (Caroline), van de Poll-Franse LV, Ottevanger PB (Nelleke), Ezendam NPM. Presence of gastro-intestinal symptoms in ovarian cancer patients during survivorship: a cross-sectional study from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(6):2285-93.

18. Techata A, Muangmool T, Wongpakaran N, Charoenkwan K. Effect of cancer stage on health-related quality of life of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2022 Jan;42(1):139-45.

19. Eakin CM, Norton TJ, Monk BJ, Chase DM. Management of nausea and vomiting from poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor therapy for advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2020 Nov;159(2):581-7.

20. Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, Rasu R, Wolf JK, Bevers MW, et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2005 Apr;13(4):219-27.

21. Ghamari D, Dehghanbanadaki H, Khateri S, Nouri E, Baiezeedi S, Azami M, et al. The Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Women with Ovarian Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2023;24(10):3315-25.

22. Hill EM, Hamm A. Intolerance of uncertainty, social support, and loneliness in relation to anxiety and depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2019 Mar;28(3):553-60.

23. Liang MI, Simons JL, Herbey II, Wall JA, Rucker LR, Ivankova NV, et al. Navigating job and cancer demands during treatment: A qualitative study of ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2022 Sep;166(3):481-6.

24. Campbell R, King MT, Stockler MR, Lee YC, Roncolato FT, Friedlander ML. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Ovarian Cancer: Facilitating and Enhancing the Reporting of Symptoms, Adverse Events, and Subjective Benefit of Treatment in Clinical Trials and Clinical Practice. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2023;14:111-26.

25. Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2003 Aug;83(8):713-21.

26. Cashin AG, McAuley JH. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J Physiother. 2020 Jan;66(1):59.

27. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Mar 3;85(5):365-76.

28. Osoba D, Aaronson N, Zee B, Sprangers M, te Velde A. Modification of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 2.0) based on content validity and reliability testing in large samples of patients with cancer. The Study Group on Quality of Life of the EORTC and the Symptom Control and Quality of Life Committees of the NCI of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 1997 Mar;6(2):103-8.

29. Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, Hammerlid E, van Pottelsberghe C, Curran D, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2000 Sep;36(14):1796-807.

30. Davda J, Kibet H, Achieng E, Atundo L, Komen T. Assessing the acceptability, reliability, and validity of the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) in Kenyan cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. J Patient-Rep Outcomes. 2021 Jan 7;5(1):4.

31. Zang Y, Qiu Y, Sun Y, Fan Y. Baseline functioning scales of EORTC QLQ-C30 predict overall survival in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: a meta-analysis. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2024 Jun;33(6):1455-68.

32. Clarke NA, Braverman J, Worthy G, Shaw JW, Bennett B, Dhanda D, et al. A Review of Meaningful Change Thresholds for EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G Within Oncology. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2024 Apr;27(4):458-68.

33. Jassim G, AlAnsari A. Reliability and Validity of the Arabic Version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 Questionnaires. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:3045-52.

34. Gadisa DA, Gebremariam ET, Ali GY. Reliability and validity of Amharic version of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 modules for assessing health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients in Ethiopia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019 Dec 12;17(1):182.

35. Cankurtaran ES, Ozalp E, Soygur H, Ozer S, Akbiyik DI, Bottomley A. Understanding the reliability and validity of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in Turkish cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008 Jan;17(1):98-104.

36. Guzelant A, Goksel T, Ozkok S, Tasbakan S, Aysan T, Bottomley A. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: an examination into the cultural validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004 May;13(2):135-44.

37. Shuleta-Qehaja S, Sterjev Z, Shuturkova L. Evaluation of reliability and validity of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30, Albanian version) among breast cancer patients from Kosovo. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:459-65.

38. Nicklasson M, Bergman B. Validity, reliability and clinical relevance of EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC13 in patients with chest malignancies in a palliative setting. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2007 Aug;16(6):1019-28.

39. Lundy JJ, Coons SJ, Aaronson NK. Test-Retest Reliability of an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) Version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. The Patient. 2015 Apr;8(2):165-70.

40. Shih CL, Chen CH, Sheu CF, Lang HC, Hsieh CL. Validating and improving the reliability of the EORTC qlq-c30 using a multidimensional Rasch model. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2013;16(5):848-54.

41. Kyriaki M, Eleni T, Efi P, Ourania K, Vassilios S, Lambros V. The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample. Int J Cancer. 2001 Oct 1;94(1):135-9.

42. Ford ME, Havstad SL, Kart CS. Assessing the reliability of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in a sample of older African American and Caucasian adults. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2001;10(6):533-41.

43. Wallwiener M, Matthies L, Simoes E, Keilmann L, Hartkopf AD, Sokolov AN, et al. Reliability of an e-PRO Tool of EORTC QLQ-C30 for Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer: Prospective Randomized Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Sep 14;19(9):e322.

44. Kontodimopoulos N, Samartzis A, Papadopoulos AA, Niakas D. Reliability and validity of the Greek QLQ-C30 and QLQ-MY20 for measuring quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:842867.

45. Maringwa J, Quinten C, King M, Ringash J, Osoba D, Coens C, et al. Minimal clinically meaningful differences for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BN20 scales in brain cancer patients. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2011 Sep;22(9):2107-12.

46. Musoro JZ, Coens C, Fiteni F, Katarzyna P, Cardoso F, Russell NS, et al. Minimally Important Differences for Interpreting EORTC QLQ-C30 Scores in Patients With Advanced Breast Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019 Jun 4;3(3):pkz037.

47. Giesinger JM, Kuijpers W, Young T, Tomaszewski KA, Friend E, Zabernigg A, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance for four key domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30: physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue and pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016 Jun 7;14:87.

48. Raman S, Ding K, Chow E, Meyer RM, van der Linden YM, Roos D, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in the EORTC QLQ-C30 and brief pain inventory in patients undergoing re-irradiation for painful bone metastases. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2018 Apr;27(4):1089-98.

49. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998 Jan;16(1):139-44.

50. Zeng L, Chow E, Zhang L, Tseng LM, Hou MF, Fairchild A, et al. An international prospective study establishing minimal clinically important differences in the EORTC QLQ-BM22 and QLQ-C30 in cancer patients with bone metastases. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2012 Dec;20(12):3307-13.

51. Gallardo-Rincón D, Toledo-Leyva A, Bahena-González A, Montes-Servín E, Muñoz-Montaño W, Coronel-Martínez J, et al. Validation of the Mexican-Spanish Version of the EORTC QLQ-OV28 Instrument for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Women with Ovarian Cancer. Arch Med Res. 2020 Oct;51(7):690-9.

52. Paradowski J, Tomaszewski KA, Bereza K, Tomaszewska IM, Pasternak A, Paradowska D, et al. Validation of the Polish version of the EORTC QLQ-OV28 module for the assessment of health-related quality of life in women with ovarian cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014 Feb;14(1):157-63.

53. Akdemir Y, Cam Ç, Ay NP, Karateke A. Validation of the Turkish version of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-OV28 ovarian cancer specific quality of life questionnaire. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Mar;17(1):52-7.

54. Greimel E, Bottomley A, Cull A, Waldenstrom AC, Arraras J, Chauvenet L, et al. An international field study of the reliability and validity of a disease-specific questionnaire module (the QLQ-OV28) in assessing the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2003 Jul;39(10):1402-8.

55. Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: Past, Present and Future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127-37.

56. Yost KJ, Thompson CA, Eton DT, Allmer C, Ehlers SL, Habermann TM, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) is valid for monitoring quality of life in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013 Feb;54(2):290-7.

57. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1993 Mar;11(3):570-9.

58. Basen-Engquist K, Bodurka-Bevers D, Fitzgerald MA, Webster K, Cella D, Hu S, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-ovarian. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001 Mar 15;19(6):1809-17.

59. Lee M, Lee Y, Kim K, Park EY, Lim MC, Kim JS, et al. Development and Validation of Ovarian Symptom Index-18 and Neurotoxicity-4 for Korean Patients with Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer. Cancer Res Treat Off J Korean Cancer Assoc. 2019 Jan;51(1):112-8.

60. Cella D, Lenderking WR, Chongpinitchai P, Bushmakin AG, Dina O, Wang L, et al. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue is a reliable and valid measure in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. J Patient-Rep Outcomes. 2022 Sep 23;6(1):100.

61. Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Dec;34(11–12):1328-36.

62. Wagner LI, Berg SR, Gandhi M, Hlubocky FJ, Webster K, Aneja M, et al. The development of a Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) questionnaire to assess dermatologic symptoms associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (FACT-EGFRI-18). Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2013 Apr;21(4):1033-41.

63. Pozzar RA, Xiong N, Hong F, Wright AA, Goff BA, Underhill-Blazey ML, et al. Perceived patient-centered communication, quality of life, and symptom burden in individuals with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Nov;163(2):408-18.

64. Hilpert F, Du Bois A. Patient-reported outcomes in ovarian cancer: are they key factors for decision making? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018 Oct;18(sup1):3-7.

65. Kennedy F, Shearsmith L, Holmes M, Peacock R, Lindner OC, Megson M, et al. ’We do need to keep some human touch’-Patient and clinician experiences of ovarian cancer follow-up and the potential for an electronic patient-reported outcome pathway: A qualitative interview study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022 Mar;31(2):e13557.