Abstract

Introduction: Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysms (TICAs) and penetrating cerebrovascular injuries (PCVI) complicate gunshot wounds to the head (GSWH) and other forms of penetrating traumatic brain injury (pTBI). Recent developments in neuroimaging have allowed early detection of these lesions in the minutes and hours following the initial injury. CT angiography (CTA) and digitally subtracted angiography (DSA) have different sensitivity, periprocedural risks, and logistical limitations. Growing evidence is defining their role in clinical practice.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was performed for published articles treating the use of CTA and DSA to diagnose PCVI and TICAs after pTBI and GSWH. Four series, three retrospective and one prospective, were selected for this review.

Results: In three retrospective and one prospective series (with a sensitivity of ~70% in the former studies vs 36% in the latter), DSA emerges as the modality of choice to study the intracranial vasculature of patients that suffered pTBI. Nonetheless, the use of CTA in the first hours after the injury can provide a wealth of information in emergent scenarios where TICAs and PCVIs can significantly affect surgical management and risk. Further, a significantly higher incidence of TICAs was reported in the first hours after civilian GSWH via CTA.

Conclusions: DSA and CTA emerged as two complementary techniques in the study and management of PCVI and TICA related to pTBI and GSWH. Their integration can provide a safe approach to the emergent surgical management of vascular lesions via CTA, allowing for delayed DSA characterization after neurological and hemodynamical stabilization.

Keywords

Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysms, penetrating cerebrovascular injuries, complicate gunshot wounds to the head, CT angiography

Introduction

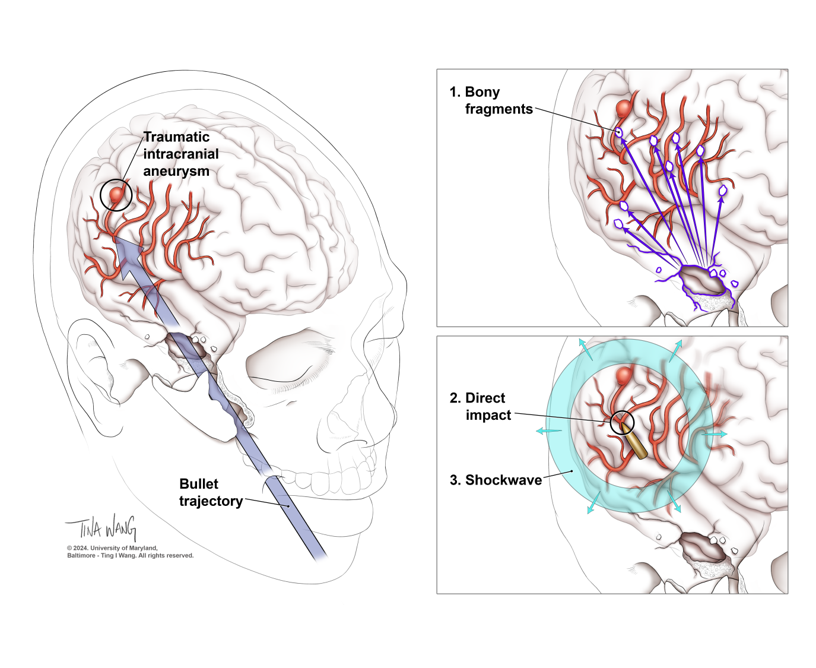

Traumatic intracranial pseudoaneurysms (TICAs) and penetrating cerebrovascular injuries (PCVI) are a frequent complication of gunshot wounds to the head (GSWH)[1]. Their occurrence, mainly due to more sophisticated imaging technologies, including the introduction of computed tomography angiography (CTA) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA), has significantly increased since the first clinical reports in the 1970s [2-4]. Delayed cerebral angiograms from a few days up to several weeks after the initial injury were standard of care in the early series from the Iran-Iraq and the Lebanese Civil wars [5-11]. These provided the first evidence of TICAs secondary to GSWH or shrapnel injury, highlighting their clinical importance and significant mortality (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Traumatic intracranial aneurysm formation. Craniofacial and pterional entry sites have been associated with higher risk of TICA development (panel A). Pseudoaneurysms arise from local arterial wall damage, with formation of a local hematoma and delayed recanalization, expansion, rupture. Bony and shell fragments (panel B), as well as the direct impact from the bullet and the indirect damage caused by the shockwave (panel C), contribute to local damage and TICA formation.

In the last decades we have witnessed to another shift in timing of diagnosis as CTAs and DSAs have become more available and refined [12-14]. This constitutes a major advancement in the acute care of penetrating traumatic brain injury (pTBI), thanks to the combination of bone, parenchymal, CSF and wound-related information provided by CTAs. Despite these advantages, the sensitivity and specificity of CT angiography can be affected by metal and bony fragments, contrast timing, lower spatial and temporal resolution [15-19]. Further, PCVI is usually located along the harboring vessel and not at a branching point. Beam-hardening artifacts can reduce the signal in small arteries located underneath the calvarium, lowering the detection rate. On the other hand, while DSA is the current gold-standard for vascular pathologies, its logistical complexity, higher costs, and invasiveness, make it less desirable in the hyper-acute phase after pTBI, when patients can be unstable and may need urgent surgical intervention. In recent years, several studies have looked at the ability of CTAs and DSAs to detect vessel injuries after pTBI. Given the significant increase in civilian GSWHs, and frequent retention of debris in the wound tract, special attention has been given to firearm-related vascular injuries. Several series performed at US Trauma Centers have elucidated the role and complementarity of each diagnostic modality, first with retrospective analyses, and more recently with a prospective study [12,13,19-21]. Here we systematically review the contribution of CTA and DSA to the diagnosis of penetrating cerebrovascular injury (PCVI) and TICAs after GSWH and, in rare occasions, other forms of pTBI. Their timing, clinical integration, sensitivity and specificity, as well as their ability to guide treatment course, will be examined.

Methods

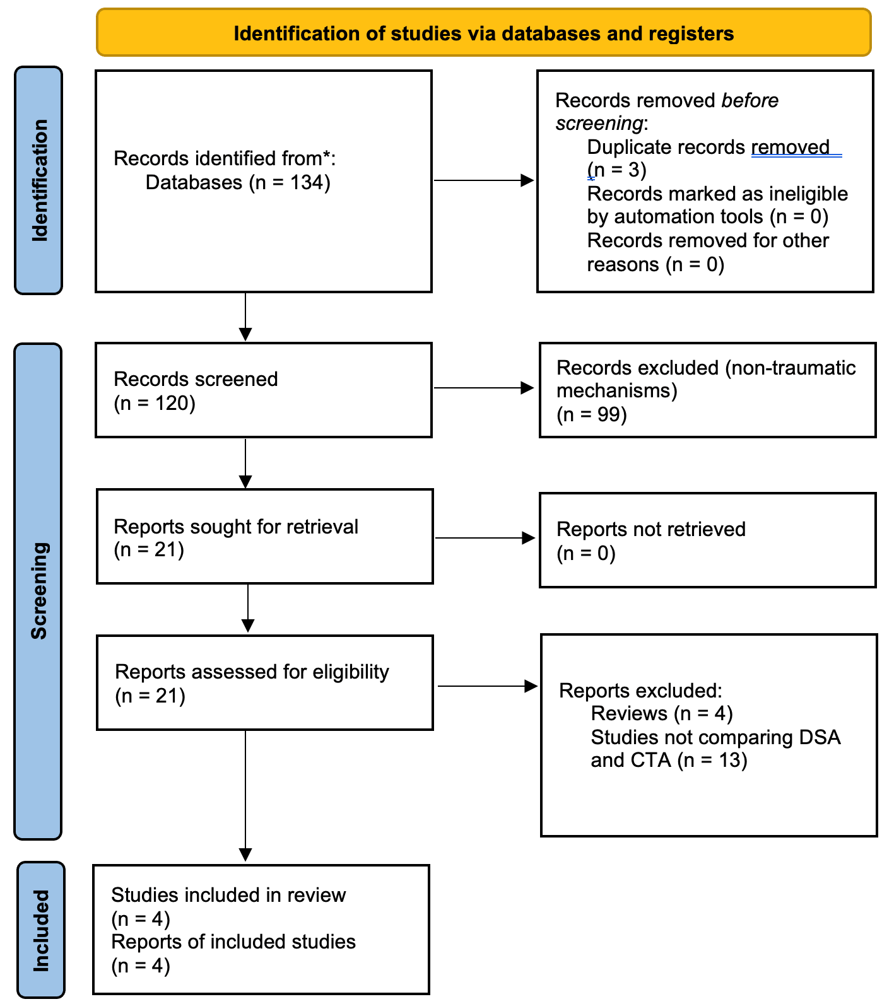

A systematic review of the literature was performed for published articles treating the use of CTA and DSA to diagnose PCVI and TICAs after pTBI and GSWH. The systematic review was confined to publications in the past 30 years, as these modalities became available during this timeframe (modern day 3D DSA was introduced in the 1990s). The PubMed database was queried to identify publications regarding this topic, and the full manuscripts were carefully read. PubMed searches included combinations of “CTA” and “DSA” with either “traumatic aneurysm” or “vascular lesion”. Abstracts were reviewed. Only manuscripts presenting new clinical research comparing CTA and DSA in penetrating brain injury were included. Specifically, evidence focused on the contribution of each modality to surgical patient care, as well as on the performance of the modality itself, was gathered. Full texts were investigated and considered in the final analysis. Abstracts lacking a full-length manuscript, reviews, clinical studies on other applications of CTA and DSA, clinical studies treating non-traumatic brain injury were excluded. Records were independently screened by the authors and no automation tools were used. Figure 2 summarizes and outlines the selection process used for this systematic review. A total of 4 studies meeting these criteria were identified and considered for the final analysis. Three of these studies compared head-to-head the sensitivity, specificity and PPV/NPV of these modalities. One article missing these data was included in the results and discussion, but excluded from tables that summarize the overall performance of these techniques. Data were collected and presented in the manuscript. Results were also interpreted in the “Discussion” section. Selection bias might have affected some of these studies, especially given the retrospective nature of most of this evidence. Given the limited availability of prospective studies on this topic, we chose to include both types of manuscripts. This review was conducted according to the PRISMA guideline [22,23](Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. Flow diagram of the systematic research and selection process used to identify the final papers in this review.

Results

Current guidelines for the Management of Penetrating Brian Injury [24], while discussing both modalities, recommend the use of DSA in cases where the risk of cerebrovascular injury is significant. Unfortunately, growing evidence suggests that PCVI and TICAs may be more common than previously thought, especially in individuals that suffered a GSWH. For this reason, a fast and relatively sensitive modality such as CTA might be the only feasible option in the first hours after the injury. Nonetheless, given the frequent presence of metal and bony fragments along the GSWH tract, and intrinsic lower spatial and temporal resolution of CTA, a direct comparison of these modalities is warranted. In the last two decades, several studies have approached this issue in a retrospective and prospective fashion.

Bodanapally et al. first compared CTA and DSA acquired within 24 hours of each other [13]. Enrolled patients had suffered pTBI with a complete calvarial fracture and involvement of brain tissue. Importantly, while only cranial injuries were considered in this series, patients with retained metal fragments limiting the visualization of third-order branches of intracranial arteries were excluded from the analysis. In the final cohort, 40 subjects suffered a GSWH, 4 had stab wounds, and a patient was impaled with a piece of wood. All the patients in the study received a CTA within 12 hours from admission, with an average interval between CTA and DSA of 7.4 hours. Scans were then retrospectively and blindly interpreted by a Junior Radiology Attending, a Senior Radiology Fellow and a Senior Radiology Resident. Images were scored and classified as either TICA, occlusion, dissection or segmental narrowing, active bleeding, arteriovenous fistulas, mural thrombus. Importantly, 22 injuries were detected in a total of 45 patients, among which were 8 dissections, 7 TICAs, 6 occlusions, and 1 carotid-cavernous fistula (Table 1). Three of the 7 TICAs presented on day 4 post-injury due to bleeding at the site or repeat DSA. Overall, CTA sensitivity reached 72.7% (16/22; 95% CI 49.8%–89.3%); with a specificity of 93.5% (29/31; 95% CI 78.6%–99.2%); a PPV of 88.9% (16/18; 95% CI 65.3%–98.6%), and a NPV of 82.9% (29/35; 95% CI 66.4%– 93.4%) (Table 2). For all interpreters the sensitivity value was comprised between 70% and 85%. When patients with retained metal artifacts were included, the sensitivity decreased to 66.7% (95% CI 44.7%–83.6%), while the specificity increased to 94.3%. Interestingly, the adjudicator’s sensitivity and specificity, as well as the PPV and NPV, reached 100% for TICAs. In conclusion, this study provided first evidence of the ability of CTAs of the head to diagnose TICAs and other forms of PCVI after pTBI in the acute setting. In a second manuscript, Bodanapally et al. focused on refining and updating the risks factors of PCVI on admission CTA plus short-interval DSA, similarly to what had been done with the previous generation of techniques [12]. The historical data on PCVI and TICAs was in fact obtained from wartime studies, and the majority came from non-contrasted CTs or plain radiography. In these studies, entry and exit wounds, projectiles’ trajectories, and vessel injuries were assessed on conventional angiography several days/weeks post-injury. In the final cohort of 55 patients, 43 patients suffered a GSWH, 7 were stabbed, 4 had a nail gun injury and 1 was impaled by a wooden piece. The initial DSA study was performed 7.9 hours after admission, and 25 patients had a follow up scan within the first 13 days from admission. 11 TICAs – 7 of which in patients that suffered a GSWH, 8 dissections, 6 occlusions, and 3 carotid-cavernous fistulas were uncovered, all in the anterior circulation except for a lesion in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. These patients showed higher proportions of entry wounds in the frontobasal-temporal area, trajectories transecting bilateral hemispheres or in proximity of the COW, presence of SAH (except for GSWH, where a higher SAH score was the only factor significantly associated with the risk of development) and higher modified Hijdra SAH score, presence of IVH and higher modified Graeb score. This study consolidated and updated the analogic evidence gathered in the 1970s-1990s in wartime series via a retrospective analysis of radiographic parameters associated with vascular injuries. Further, it added a layer of additional complexity by using complex scores to quantify intracranial blood burden and confirmed the vascular findings by pairing CT scans with early DSAs. Ares and colleagues took this concept one step further, retrospectively comparing admission head CTAs and DSAs performed within the first 24 hours for all patients that suffered pTBI [20]. Patients were then stratified using a Biffl grading scheme modified for PCVI (Table 1). In this cohort, 56 patients were diagnosed with pTBI (42 - 75% - had a cranial injury, while 14 - 25% - had cervical trauma). 48 subjects suffered a GSWH. Interestingly, among the 24 patients with a CTA suggestive of PCVI, 14 (58%) were confirmed on DSA while 10 (42%) were negative. On the other hand, among 32 patients with negative CTA, 9 (28%) were diagnosed with a vascular injury on angiogram. Further, DSA upgraded the modified-Biffl grading in 30% of cases and achieved a lower score in another 30% of the cohort. Of 7 injuries requiring endovascular treatment, only 4 were discovered on CTA, while the remaining 3 were found only on DSA. Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of CTA for diagnosing any PCVI was 72% and 63%, respectively. The PPV was 61% with a NPV of a negative CTA of 70%. Importantly, shrapnel and/or metal fragments appeared to be present along the injury tract of almost half the CTAs that proved false positive or false negative (Table 2). Several limitations of early CTA emerged from these retrospective series. The possible selection bias present when choosing which patients should proceed to DSA after pTBI, the effect of metal artifacts on CTA, and the significant number of missed lesions are among the most relevant. To answer these questions, a prospective multicenter study was carried out by Meyer et al. [21]. Here, pTBI patients were scanned with admission head CTA, followed by DSA within the following 2 days. A standardized protocol that included bilateral internal and external carotid arteries, and bilateral vertebral arteries was enforced for DSAs. Again, most patients suffered a GSWH (63/76, 86% of the total). Forty-seven PCVIs were diagnosed by DSA in 33 subjects (45.2%), and CTA missed ≥ 1 cerebrovascular injury in 21 patients (63.6%). Among these were 9 TICAs, 3 arterial occlusions, 8 dural AV fistulas, and 6 carotid-cavernous fistulas. Further, 6 false positives were uncovered by DSA - 2 pseudoaneurysms, 1 arterial occlusion, 3 venous sinus occlusions (Table 1).This study reported an overall incidence of PCVIs of 45.2%, in line with other recent civilian studies. A sensitivity of 36.4% (95% CI 20.4%–54.9%), with a specificity of 85.0% (95% CI 70.2%–94.3%), was calculated for CTA. The CTA PPV was 66.7%, with a NPV of 61.8%. Finally, the number of DSAs needed to treat a PCVI was 5.6 (Table 2). In conclusion, while the first three studies presented here might have suffered from selection bias secondary to the retrospective nature of their data, the last study tries to address this limitation by prospectively – although in a non-blinded fashion – enrolling pTBI patients. A time bias always exists in these studies, as vascular injuries might worsen or resolve on their own before, between and after studies are performed.

|

|

Bodanapally et al. 2014 |

Bodanapally et al. 2015 |

Meyer et al. 2024 |

Modified Biffl Grade |

Ares et al. 2019 |

|

TICA |

7 |

11 |

13 |

mBiffl 1 |

10 |

|

Dissections |

8 |

8 |

- |

mBiffl 2 |

2 |

|

Occlusions |

6 |

6 |

11 |

mBiffl 3 |

7 |

|

Carotid-cavernous fistulas |

1 |

3 |

6 |

mBiffl 4 |

2 |

|

Arterio-venous fistulas |

- |

- |

8 |

mBiffl 5 |

4 |

|

Venous sinus occlusion |

- |

- |

9 |

|

|

|

|

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

PPV |

NPV |

|

Meyer et al. 2024 |

36.4% |

85.0% |

66.7% |

61.8% |

|

Ares et al. 2019 |

72% |

63% |

61%

|

70% |

|

Bodanapally et al.* 2014 |

72.7%

|

93.5%

|

88.9%

|

82.9%

|

Discussion

Acute traumatic pseudoaneurysms and other arterial and venous injuries are a frequent finding in GSWHs and other pTBI. For TICAs, an incidence of 2-40% has historically been reported in studies using conventional angiography performed in the days/weeks after the injury [3,4,6,14]. Several series investigating the vascular damage after civilian GSWHs reported an overall incidence of PCVI of ~50% on admission CTA. Patients with PCVI show higher odds of mortality, lower GSW and lower odds of good independent, functional outcomes [4]. Lastly, while early series on PCVI secondary to pTBI were mainly stemming from military backgrounds, the recent increase in civilian GSWHs has determined a reconsideration of PCVIs in these scenarios [14,25]. An important factor is the lower energy carried by civilian GSWH. Similarly to shrapnel-related injuries, these lesions might in fact cause only a partial arterial wall injury that later develops into a TICA. For these reasons, and in consideration of the significant advancements in CTA and DSA technology over the last three decades, a consensus on the imaging modality of choice for pTBI needs to be reached. CTA, with its intrinsic efficiency, provides a significant amount of information on bony, parenchymal, and wound-related changes. The addition of perfusion imaging can provide data on blood flow to the brain and help identify areas of stroke. Unfortunately, its sensitivity and specificity can be affected by metal and bony fragments, contrast timing, and lower spatial and temporal resolution. Beam-hardening artifacts can reduce the signal in small arteries located underneath the calvarium and in the petrous segment of the carotid. On the other hand, DSA provides 2D and 3D reconstructions of the entire vasculature, subtracting background noise and minimizing metal artifact. It is considered the gold standard in the study of intracranial vessels. Nonetheless, its invasive nature, need for an interventional complex team and dedicated angiography suite, higher risk of complications, longer exam duration make it less suitable for emergent situations where immediate brain decompression and bleeding control needs to be achieved [16]. Given the high morbidity and mortality that PCVIs and TICAs carry, and the emergent scenario in which they usually present, performing a vessel study within the first 48 hours from admission is of paramount importance. The studies presented here provide several important elements to tailor the imaging modality on the patient’s needs. This review, despite the known limitations of retrospective evidence, aims at providing a compendium of clinical indications and uses of these imaging techniques in pTBI.

Choosing Vessel Imaging Modality before Surgical Intervention

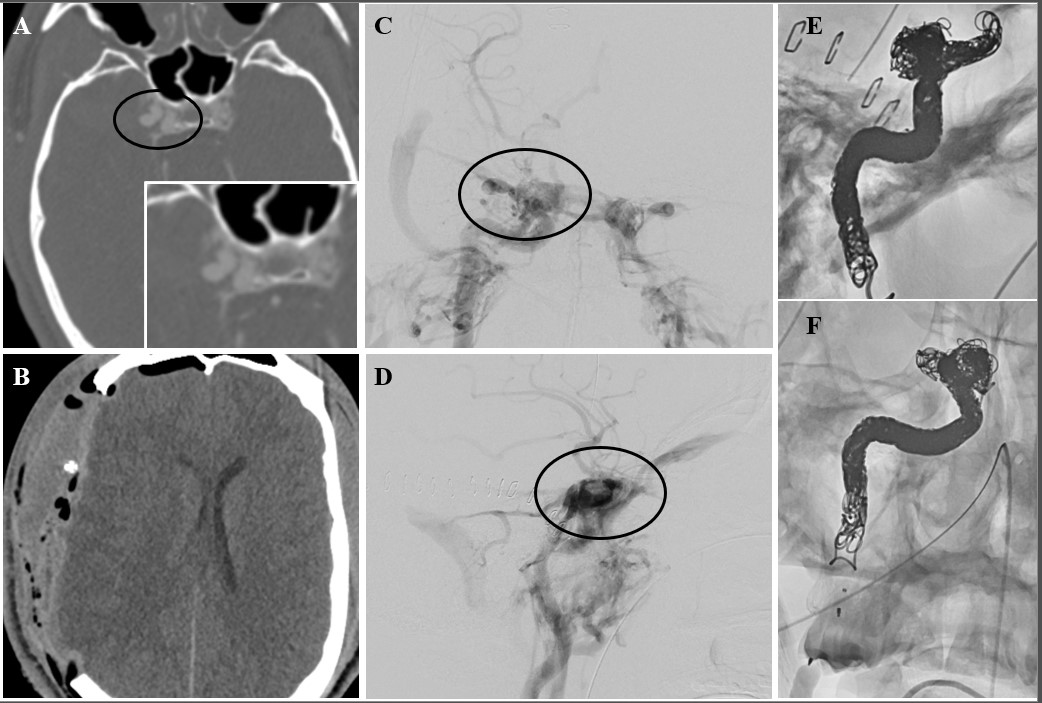

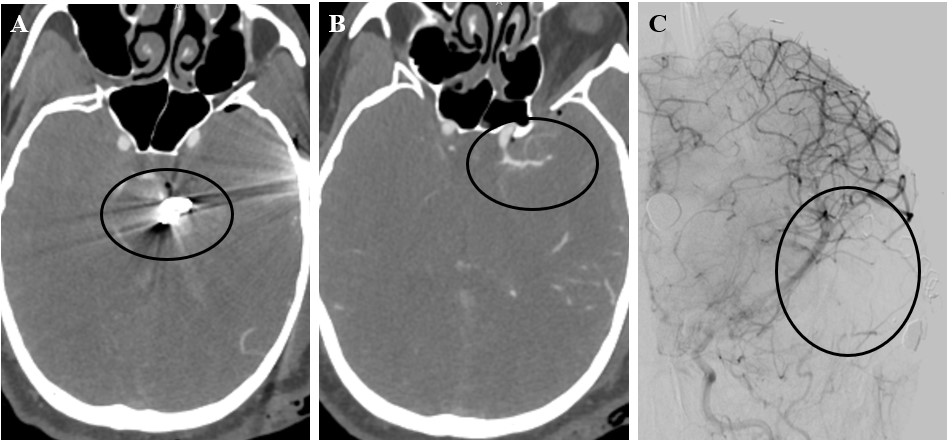

In a recent study, Serra et al. suggested that a significant number of patients, up to 20% of those suffering a civilian GSWH, can develop a pseudoaneurysm in the hyper-acute window [14]. This number, despite being significantly higher than previous estimates, does not include other types of vascular injuries [6,9,11,25-27]. Importantly, while this study showed a CTA sensitivity in line with Meyer’s prospective study, it also demonstrated that patients presenting with a TICA had higher chances of developing an intracerebral hematoma [14]. Further, these subjects underwent surgery more often and suffered higher rates of bleed expansion and intraventricular hemorrhage. Another important factor to consider when evaluating new lesions discovered on CTA and not confirmed on DSA is the spontaneous obliteration of pseudoaneurysms, dissections, fistulas. This was again demonstrated by Serra et al. in their series, as nine patients (9/28, ~30%) underwent spontaneous TICA resolution on repeat CTA/DSA. Admission CTA might therefore cast light on the early phases after pTBI, where biological processes might explain part of the difference with DSA. In the future, further characterization with ultra-early DSA might be warranted in these subjects. This will allow to confirm the presence of TICAs and other vascular injuries seen on CTA, address these lesions early via endovascular technique, and provide important data to validate the use of CT in pTBI settings. A clinical trial of ultra-early CTA/DSA may significantly improve our understanding of GSWH pathophysiology, a problem that has become highly relevant in recent years, following the increase in civilian GSWs. CTA, despite the recent advancements in its sensitivity, is still outperformed by DSA in terms of pure sensitivity and specificity. Given its availability it can nonetheless play a pivotal role in the preoperative evaluation of pTBI – TICAs and PCVIs can be quickly identified, and the surgical approach modified to address these lesions. If noticed on admission CTA, TICAs can be trapped and excised or cauterized, reducing blood loss and the risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figures 3 and 4). On the other hand, early DSA allows for direct obliteration of the lesion via Onyx, coils, glue [25,28,29]. While the advantages of treatment during angiography are frequently highlighted and used to justify early DSA, it is evident that in emergent scenarios where immediate decompression and debridement need to be performed, this exam can significantly delay care and affect patient prognosis. Further, open treatment of TICAs and PCVI has been routinely performed for decades, and it should be stressed that CTA streamlines surgical interventions by allowing the treatment of the lesion and cerebral decompression during the same session.

Figure 3. 22-year-old gentleman who suffered a right temporal and pterional stab wound. Admission CTA showed an ipsilateral acute subdural hematoma (aSDH), as well as a cavernous carotid pseudoaneurysm with a traumatic type A high-flow fistula. The patient was taken emergently to the operating room and parallel decompressive hemicraniectomy and exposure/clamping of the common carotid artery in the neck were performed. The patient was transported to the IR suite after cerebral decompression was achieved. Coil-sacrifice of the right internal carotid artery was performed using packing coils and microvascular plugs. The collateral circulation was also assessed before and after carotid sacrifice and found to be excellent. The patient made a full recovery without residual neurologic deficits.

Figure 4. 35-year-old man who suffered a left temporal GSWH. After the injury, bony fragments were located along the GSWH tract in the temporal lobe, while the bullet was lodged along the falx at convexity. Narrowing of the left M1 segment of the MCA was noticed on admission CTA. Several truncated M3 and M4 branches were also visualized. The patient was emergently taken to the OR for decompression and the Sylvian fissure was packed with gelfoam to control bleeding from transected vessels.

Post-operative DSA shows several truncated distal MCA branches and mass effect from packing. Follow-up DSA on day 10 post-injury failed to demonstrate additional vascular injuries.

CTA vs DSA in Selected Lesions

In retrospective series, CTA showed a sensitivity of ~70%, with a specificity ranging from 63 to 93% when performed in the first two days from admission [12,13,20]. When studying this modality prospectively, Meyer et al. reported a sensitivity of 36.4% (95% CI 20.4%–54.9%) and a specificity of 85% [21]. Several factors might explain this difference. First, an inherent selection bias might have been present in retrospective series, as only patients with a high suspicion of vascular injury were selected for additional imaging via DSA. Further, patients with PCVI discovered on admission CTA have historically been worked up with DSA to better characterize the feeding and draining vessels, relationship with the intracranial vasculature, size and shape of the lesion, driving up the sensitivity/specificity of CTA. The interval between admission CTA and DSA, usually in the order of hours to days, might also affect the rate of lesion recanalization of thrombosis, leading to over- or underestimation of the true PCVI rate. Despite these differences between retrospective and prospective studies, CTA retains a significant value in a selected patient population. For pTBI patients in which the wound does not cross regions of the skull that can cause significant streak artifact (parietal and frontal squama, suboccipital keel, mastoid and petrous apex), with a few or no bony/metal fragments, and with minimal intracranial hemorrhage, the admission CTA might be enough to rule out vessel pathology. The addition of a scheduled follow-up scan might also reduce the rate of false negatives.

In the future, the integration of these modalities may fill the technical limitations of each technique. With the advent of hybrid neurosurgical operating rooms live intra- and post-operative imaging will allow to evaluate these lesions during or immediately after wound debridement and cerebral decompression with DSA. Further, high resolution cone beam CTAs can provide high-quality vessel images while the patient is on the table, without sacrificing the soft tissue and bone information provided by a regular CTA.

Conclusions

In conclusion, recent evidence has prospectively demonstrated higher sensitivity and specificity of catheter-based DSA over admission CTA in pTBI. Nonetheless, both techniques carry several advantages and complement each other in the acute phases following penetrating brain lesions. CTA retains significant value in the emergent preoperative evaluation of patients in need of cerebral decompression and at risk for PCVI. Further, it helps screening patients for additional imaging and/or treatment. DSA on the other hand, with its peculiar sensitivity and specificity, remains the gold standard for the evaluation of vessel injuries. PCVI and TICA treatment can be achieved during the same session and subjects at increased risk can receive repeat vascular imaging within the first weeks after injury.

Supplementary Table 1

Modified Biffl grading as suggested by Ares et al. in their clinical series. Modifications are bolded.

Supplementary Figure 1

PRISMA criteria checklist.

Author Contribution

RS acquired, analyzed, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. RS, BA, and GS provided review & editing, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Shock Trauma Center for the support and guidance throughout the entire project.

Disclosures

The author(s) have no competing interest to disclose.

Funding Statement

There was no funding provided for this research except for the technical support of the Shock Trauma Center and the Department of Neurosurgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Transparency, Rigor, Reproducibility

All data and materials included in these studies will be freely shared with any interested party. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors.

References

2. Jinkins JR, Dadsetan MR, Sener RN, Desai S, Williams RG. Value of acute-phase angiography in the detection of vascular injuries caused by gunshot wounds to the head: analysis of 12 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Aug;159(2):365-8.

3. Mansour A, Loggini A, El Ammar F, Ginat D, Awad IA, Lazaridis C, Kramer C, Vasenina V, Polster SP, Huang A, Olivera Perez H, Das P, Horowitz PM, Zakrison T, Hampton D, Rogers SO, Goldenberg FD. Cerebrovascular Complications in Early Survivors of Civilian Penetrating Brain Injury. Neurocrit Care. 2021 Jun;34(3):918-26.

4. Lamanna JJ, Gutierrez J, Alawieh A, Funk C, Rindler RS, Ahmad F, Howard BM, Gupta SK, Gimbel DA, Smith RN, Pradilla G, Grossberg JA. Association of Cerebrovascular Injury and Secondary Vascular Insult With Poor Outcomes After Gunshot Wound to the Head in a Large Civilian Population. Neurosurgery. 2024 Feb 1;94(2):240-50.

5. Aarabi B. Traumatic aneurysms of brain due to high velocity missile head wounds. Neurosurgery. 1988 Jun;22(6 Pt 1):1056-63.

6. Aarabi B. Management of traumatic aneurysms caused by high-velocity missile head wounds. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995 Oct;6(4):775-97.

7. Aarabi B, Mossop C, Aarabi JA. Surgical management of civilian gunshot wounds to the head. In: Grafman J, Salazar AM, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Elsevier; 2015. pp. 181-93.

8. Haddad FS. Wilder Penfield Lecture: nature and management of penetrating head injuries during the Civil War in Lebanon. Can J Surg. 1978 May;21(3):233-7, 240.

9. Haddad FS, Haddad GF, Taha J. Traumatic intracranial aneurysms caused by missiles: their presentation and management. Neurosurgery. 1991 Jan;28(1):1-7.

10. Rahimizadeh A, Abtahi H, Daylami MS, Tabatabei MA, Haddadian K. Traumatic cerebral aneurysms caused by shell fragments. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1987;84(3-4):93-8.

11. Amirjamshidi A, Rahmat H, Abbassioun K. Traumatic aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas of intracranial vessels associated with penetrating head injuries occurring during war: principles and pitfalls in diagnosis and management. A survey of 31 cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1996 May;84(5):769-80.

12. Bodanapally UK, Saksobhavivat N, Shanmuganathan K, Aarabi B, Roy AK. Arterial injuries after penetrating brain injury in civilians: risk factors on admission head computed tomography. J Neurosurg. 2015 Jan;122(1):219-26.

13. Bodanapally UK, Shanmuganathan K, Boscak AR, Jaffray PM, Van der Byl G, Roy AK, et al. Vascular complications of penetrating brain injury: comparison of helical CT angiography and conventional angiography. J Neurosurg. 2014 Nov;121(5):1275-83.

14. Serra R, Wilhelmy B, Chen C, Oliver JD, Stokum JA, Bodanapally UK, et al. Acute Development of Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms After Civilian Gunshot Wounds to the Head. J Neurotrauma. 2024 Aug;41(15-16):1871-82.

15. Kazim SF, Shamim MS, Tahir MZ, Enam SA, Waheed S. Management of penetrating brain injury. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011 Jul;4(3):395-402.

16. Le TH, Gean AD. Neuroimaging of traumatic brain injury. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009 Apr;76(2):145-62.

17. Douglas DB, Ro T, Toffoli T, Krawchuk B, Muldermans J, Gullo J, et al. Neuroimaging of Traumatic Brain Injury. Med Sci (Basel). 2018 Dec 20;7(1):2.

18. Hawryluk GWJ, Selph S, Lumba-Brown A, Totten AM, Ghajar J, Aarabi B, et al. Neurotrauma Rep. 2022 Jun 21;3(1):240-7.

19. Velmahos GC, Degiannis E, Doll D. Penetrating trauma: a practical guide on operative technique and peri-operative management. Springer; 2012.

20. Shaban S, Huasen B, Haridas A, Killingsworth M, Worthington J, Jabbour P, et al. Digital subtraction angiography in cerebrovascular disease: current practice and perspectives on diagnosis, acute treatment and prognosis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2022 Jun;122(3):763-80.

21. Ares WJ, Jankowitz BT, Tonetti DA, Gross BA, Grandhi R. A comparison of digital subtraction angiography and computed tomography angiography for the diagnosis of penetrating cerebrovascular injury. Neurosurgical Focus. 2019 Nov 1;47(5):E16.

22. Meyer RM, Grandhi R, Lim DH, Salah WK, McAvoy M, Abecassis ZA, et al. A comparison of computed tomography angiography and digital subtraction angiography for the diagnosis of penetrating cerebrovascular injury: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2024 Feb 2;1(aop):1-4.

23. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372.

24. Tugwell P, Tovey D. PRISMA 2020. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021 Jun 1;134:A5-6.

25. Alao T, Munakomi S, Waseem M. Penetrating Head Trauma. 2024 Jan 30. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan.

26. Bell RS, Vo AH, Roberts R, Wanebo J, Armonda RA. Wartime traumatic aneurysms: acute presentation, diagnosis, and multimodal treatment of 64 craniocervical arterial injuries. Neurosurgery. 2010 Jan;66(1):66-79; discussion 79.

27. Langner S, Fleck S, Kirsch M, Petrik M, Hosten N. Whole-body CT trauma imaging with adapted and optimized CT angiography of the craniocervical vessels: do we need an extra screening examination? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008 Nov;29(10):1902-7.

28. Aarabi B, Taghipour M, Kamgarpour A. Traumatic intracranial aneurysms due to craniocerebral missile wounds. Missile wounds of head and neck. Lebanon, NH: American Association of Neurological Surgeons. 1999:293-314.

29. Acosta C, Williams PE, Clark K. Traumatic aneurysms of the cerebral vessels. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1972 May 1;36(5):531-6.

30. Horowitz MB, Kopitnik TA, Landreneau F, Ramnani DM, Rushing EJ, George E, Purdy PP, Samson DS. Multidisciplinary approach to traumatic intracranial aneurysms secondary to shotgun and handgun wounds. Surgical neurology. 1999 Jan 1;51(1):31-42.