Abstract

Heart disease is one of the top causes of healthcare expenses in the United States. Lethal ventricular cardiac arrhythmia can arise in acquired or congenital heart disease. Long QT syndrome type 3 (LQT3) is a congenital form of ventricular arrhythmia caused by mutations in the cardiac sodium channel SCN5A. Mexiletine is a Class 1 antiarrhythmic drug that inhibits INa-L and shortens the QT interval in LQT3 patients. However, slightly above therapeutic doses, Mexiletine prolongs the cardiac action potential. Mexiletine was reengineered in an iterative process called dynamic medicinal chemistry to explore structure activity relationships (SAR) for AP shortening and prolongation of AP kinetics in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs). Certain newly synthesized Mexiletine analogs showed enhanced potency and selectivity for INa-L and low proarrhythmic liability and less central nervous system toxicity than the parent compound. In an aged animal model of oxidative stress that produces early after depolarization (EAD) formation and other arrhythmogenic effects, certain Mexiletine analogs examined were observed to reverse arrhythmogenic effects. Further modification using selected deuterated Mexiletine analogs showed that improvement to pharmacologic and pharmaceutical properties can be achieved. In conclusion, studies highlighted the utility of using hiPSC-cardiomyocytes to guide medicinal chemistry and obtain new chemotypes for “cardiovascular drug discovery in a dish”.

Keywords

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), Ventricular tachycardia (VT), Ventricular fibrillation (VF), Action potential (AP), Long QT syndrome type 3 (LQT3)

Introduction

Worldwide, heart disease accounts for the greatest mortality than any other illness. In the United States, approximately one million individuals are hospitalized every year for arrhythmias, making arrhythmias one of the top causes of healthcare expenditures with a direct cost of almost $50 billion annually for diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation [1]. Another 300,000 individuals die of sudden arrhythmic death syndrome every year in the United States [2]. Arrhythmias are very common in older adults but unfortunately, drugs to treat arrhythmias have liabilities. In addition, numerous drugs have been withdrawn from the market because they induce QT prolongation and a potentially fatal ventricular tachycardia (VT), Torsade de Pointes (TdP) [3].

Drug development efforts to treat arrhythmias is challenging. However, recent advances in replication of human pathogenetic processes in vitro, using human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-based models can facilitate development of therapeutics that target specific disease mechanisms. Thus far, large-scale drug development efforts have been restricted to using iPSCs from healthy donors [4]. hiPSC-based cell toxicity evaluation can play an important role in the development of a drug candidate and adverse cardiovascular effects of drug candidates during clinical trials that can be a major reason for termination of development of drug candidates can be clarified. Prediction of drug candidate toxicity can use in vitro as well as in vivo models. A major drawback for in vivo data, however, is the lack of extrapolation from small animals to humans, due to interspecies variations. With advances in stem cell technology, application of stem cell-based toxicity testing has opened up methods to study the impact of new chemical entities not only on specific cell types, but also organs. For example, stem cell-derived three-dimensional cultures called organoids can be grown from human stem cells and from patient-derived iPSCs. These organoids have the potential to model human disease and also have potential for drug candidate testing [5,6].

Human patient-derived iPSCs can be used as a model of cell function in response to drug candidates. In addition, advances in tissue engineering, high throughput screening and microfluidics to produce disease in a dish or organ on a chip, has led to assays that are useful to understand potency as well as adverse and toxic effects of drugs to enable drug development in a dish [7]. This Commentary summarizes recent studies that describe a role of human patient-derived iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to reengineer a cardiovascular drug with liabilities (i.e., Mexiletine) to new drug candidates. Evaluation of several toxicological endpoints will be highlighted that resulted in improved drug candidates. In the future, such an approach can be paired with human efficacy and safety studies to conduct “clinical trials in a dish” studies to support development and validation of new regulatory paradigms to assess drug safety [8].

Methods

Chemistry

Test compounds were synthesized and fully characterized as described previously [9-11].

Cell culture and data acquisition

Normal and LQTS3 hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were prepared as described previously [12] and after 25 days cardiomyocytes were dissociated and plated onto Matrigel-coated 384 well tissue culture plates. VF2.1.C1/pluronic F127 dye mixture was loaded into cells and after equilibration, test compounds were incubated for 5 mins before image acquisition in a time series for each compound was conducted. Image analysis and physiological parameters were obtained using a IC200 KIC instrument (Vala Sciences, San Diego, CA) as described previously [13]. ADP75 and cardiomyocyte beat rate was determined and statistics were applied to the data.

In vitro metabolism

Metabolism of certain test compounds was done as described previously [9].

In Vivo and ex Vivo Studies

Animal work followed the Guide for Care and Use of Animals as adopted by NIH. The pharmacological effect of certain Mexiletine analogs was studied in mice and previously reported [9,10]. The effect of select Mexiletine analogs on rat heart tissue isolated from aged adult Sprague Dawley rats was examined. Administration of hydrogen peroxide to perfused isolated Langendorff rat hearts showed oxidative stress (i.e., EADs and ventricular fibrillation) [14]. Treatment of these same hearts perfused with hydrogen peroxide with certain Mexiletine analogs (10 µM) showed complete resolution of arrhythmias back to normal sinus rhythm.

Results

In vitro studies: Antiarrhythmic drugs

While efforts in drug discovery and development efforts have increased, on a percentage basis, the number of drug approvals has declined. One significant reason is adverse side effects of drug candidates to the heart. This has caused cessation of many preclinical drug development programs. This is partly due to lack of suitable humanized preclinical models. Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes have emerged as powerful non-animal tools to model heart disease, screen drug candidates, and test drug cardiotoxicity in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [15-20]. The utility of human iPSCs include non-invasive formation and integration/correlation of patient samples with rare diseases. iPSCs have been widely used in cardiac disease modelling and the study of inherited arrhythmias. The focus of the current Commentary is to detail some in vitro and in vivo aspects of cardiovascular drug development [21].

The original classification of antiarrhythmic drugs (Classes I-VI) has remained largely empirical [22] and the link between specific ionic effect(s) of a drug and suppression of a specific arrhythmia mechanism(s) remain(s) incompletely understood [23]. Nevertheless, antiarrhythmic drugs are useful for human genetic heart disorders. In cardiomyocytes, the pathological rise of the late Na current known as late INa (INa-L), originates under cardiac conditions associated with increased risk of developing ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) [24] secondary to the activation of CaMKII signaling pathway [25] and mutations of Nav1.5 channels [26, 27]. Some Class I antiarrhythmic drugs such as Mexiletine block peak INa but also display variable block of INa-L [28]. However, the potential of proarrhythmia for patients with ischemic heart disease with these agents has led to the development of more selective blockers of INa-L, with minimized effect on peak INa [29].

Peak INa occurs in less than a millisecond and underlies the rapid upstroke or phase 0 of the action potential (AP) when the activation gate and the inactivation gate on the sodium channel are both open. Over several milliseconds the current begins to decay and contributes to a notch in the AP called phase 1. Then, some of the channels are inactivated with the inactivation gate closed. There is no commonly accepted name for this phase of INa but often it is labeled “early INa.” After several milliseconds INa normally decays to <1% of peak INa. A residual current flow as INa-L and this depolarizing current along with calcium currents supports phase 2 or the plateau of the AP. The mechanisms for late INa-L at the sodium channel level are multiple but can generally be thought of as incomplete inactivation. Eventually, activating potassium currents (IKr) repolarize the membrane (phase 3 of the AP) and when the voltage decreases below the sodium channel threshold, the activation gate closes.

Current classes of antiarrhythmic drugs are not capable of selective discrimination between the pathological INa-L and the normal peak INa necessary for normal AP upstroke velocity because often, they suppress both the early and late components of the INa to an equal extent. For example, Mexiletine, a Class 1B antiarrhythmic drugs has similar effects on peak INa and INa-L. Arrhythmias can cause a multitude of chronic cardiac diseases including heart failure [30], myocardial ischemia [29], increased pro-oxidant states [31-33], and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [24,34]. Abnormal cardiac physiology can arise from pathological INa-L. For example, early after depolarizations (EADs) and EAD-mediated arrhythmia can originate from cardiomyocytes. The potent sea anemone toxin II (ATX-II) can be used as a pharmacological tool to selectively enhance cardiomyocyte INa-L with minimal effect on other ionic currents [35,24]. The selective and potent blocker (i.e., IC50 of 134 nM) of the INa-L (i.e., GS-458967) that works as a ‘gating modifier’, showed its role in decreasing EAD-mediated arrhythmias and suppressing INa-L. This is fundamentally distinct from the traditional Class 1 antiarrhythmic drugs like Mexiletine that block the peak INa channel.

Long QT syndrome-3 (LQT3)

Long QT syndrome-3 (LQT3) is characterized by abnormal heart beats caused by mutations in the sodium channel α subunit [36]. Cardiomyocytes encoding mutant sodium channels that predisposes a patient to VT and sudden death can afford a genetic congenital model of LQTS3 [37]. The cardiac conditions associated with increased risk of VT/VF include human congenital LQT3 [26, 27]. Certain patients are genetically predisposed to a potentially fatal arrhythmogenic response to Mexiletine to treat LQT3 because the drug has off-target effects on other ion channels including the hERG channel [38]. hERG conducts the rapidly activating component of the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) that is responsible for the bulk of ventricular repolarization in cardiomyocytes. Mexiletine also has minor but detectable adverse drug properties including hepatotoxicity and blood dyscrasias [36]. In addition, Mexiletine suffers from a relatively short half-life that necessitates frequent doses. Additional doses of Mexiletine can elicit CNS toxicity.

Development of potent and selective blockers of late sodium currents could offer a new and effective antiarrhythmic drug class. Below, Mexiletine analogs are described that show considerable selectivity against late INa-L without affecting their peak response [12]. Mexiletine is used to shorten QTc in LQT3 patients in the hope that this shortening will decrease the probability of lethal arrhythmias. The idea of antiarrhythmic drug therapy based on changes in ion channel gating rather than peak current block (i.e., gating modifiers) could provide a new class of drug candidates [39].

Ex vivo studies

Oxidative activation of calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) increases the INa-L and promotes EADs in isolated rat and rabbit ventricular myocytes in vitro [31-33]. This can be translated into an ex vivo model because EAD formation and other arrhythmogenic effects can be observed after administration of H2O2 to perfused Langendorff rat and rabbit hearts [14]. Oxidative stress has been shown to induce EADs in isolated myocytes in these two species. However, in vivo, perfusion of H2O2 failed to induce ventricular arrhythmias in normal healthy young rat or rabbit hearts [40]. In contrast, aged rat hearts (i.e., 24-26 months old rat hearts), showed increases in tissue fibrosis (10-90%) and decreased cell-to-cell gap junctional couplings. Perfusion of aged rat hearts with H2O2 consistently promoted EADs and led to an incidence of >90% of aged fibrotic hearts to tachycardia and fibrillation (VT/VF) [14].

A black box warning for Mexiletine (Class I) by the FDA came about after the CAST clinical trial showed that inhibition of peak Na current was ineffective and even carried greater risk of mortality [41]. It should be pointed out the black box warning followed the CAST study was based on post-myocardial infarction patients and not LQT3 patients. Later, the SWORD clinical trial with d-sotalol (Class III) [38] was done based on the idea of increasing cardiac refractoriness. Results of the CAST and SWORD studies showed drugs with Class I and Class III actions are ineffective in suppressing arrhythmia following myocardial infarction [41,42].

Case study: Development of mexiletine analogs for LQT3

As described above, LQT3 is characterized by abnormal heart beats caused by mutations in the Na+ channel [36]. Except for one publication [43], evidence for proarrhythmic effects of Mexiletine in LQT3 patients has not been reported. Mexiletine is used to shorten QTc in LQT3 patients in the hope that this shortening will decrease the probability of lethal arrhythmias. However, Mexiletine has off-target effects on other ion channels including the hERG channel [44-46]. Because Mexiletine possesses adverse properties, a goal of our work was to chemically re-engineer Mexiletine to afford new compounds with superior pharmacological and/or pharmaceutical properties. Development of compounds with increased on-target (i.e., INa-L) versus off-target IKr (i.e., hERG) selectivity was another goal. hERG inhibition is known to be associated with clinically relevant arrhythmias and EADs. Drug-induced production of EADs manifested by T-wave prolongation and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) or measurement of cessation of cardiomyocyte beating was used as a measure of cardiomyocyte toxicity.

Use of hiPSCs to chemically reengineer mexiletine

Normal and patient-derived hiPSCs are a useful source to create human cardiomyocytes to evaluate synthetic or other drug candidates in a drug development campaign. In our studies [9,12], iterative dynamic medicinal chemistry was done on a practical time scale and in 384-well multi-well format to test drug candidates. Patient iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were used in a disease-in-a-dish approach to address an important human disease, namely QT prolongation and potentially fatal VT and TdP [9,12].

Patient-derived hiPSCs cardiomyocytes that encoded mutant sodium channels that predisposed a patient to VT and sudden death afforded a genetic congenital model of LQTS3 [47]. Normal hiPSCs cardiomyocytes were used in parallel as a control. A goal was to provide a way to identify new synthetic Mexiletine analogs to reverse a pathogenic disease phenotype. Studies conducted in parallel with normal hiPSCs cardiomyocytes were also useful to identify compounds that could potentially be toxic to normal cardiomyocytes. Identification of drug candidates that were toxic to cardiomyocytes could provide insight to structural aspects of drug candidates that caused toxicity. Molecules known to cause hERG inhibition and afford clinically relevant arrhythmia were used to validate dose-dependent drug induction of toxicity [12]. We used molecules known to cause EADs as controls and observed dose-dependent PVCs to further validate the test system [12].

Mexiletine chemical reengineering

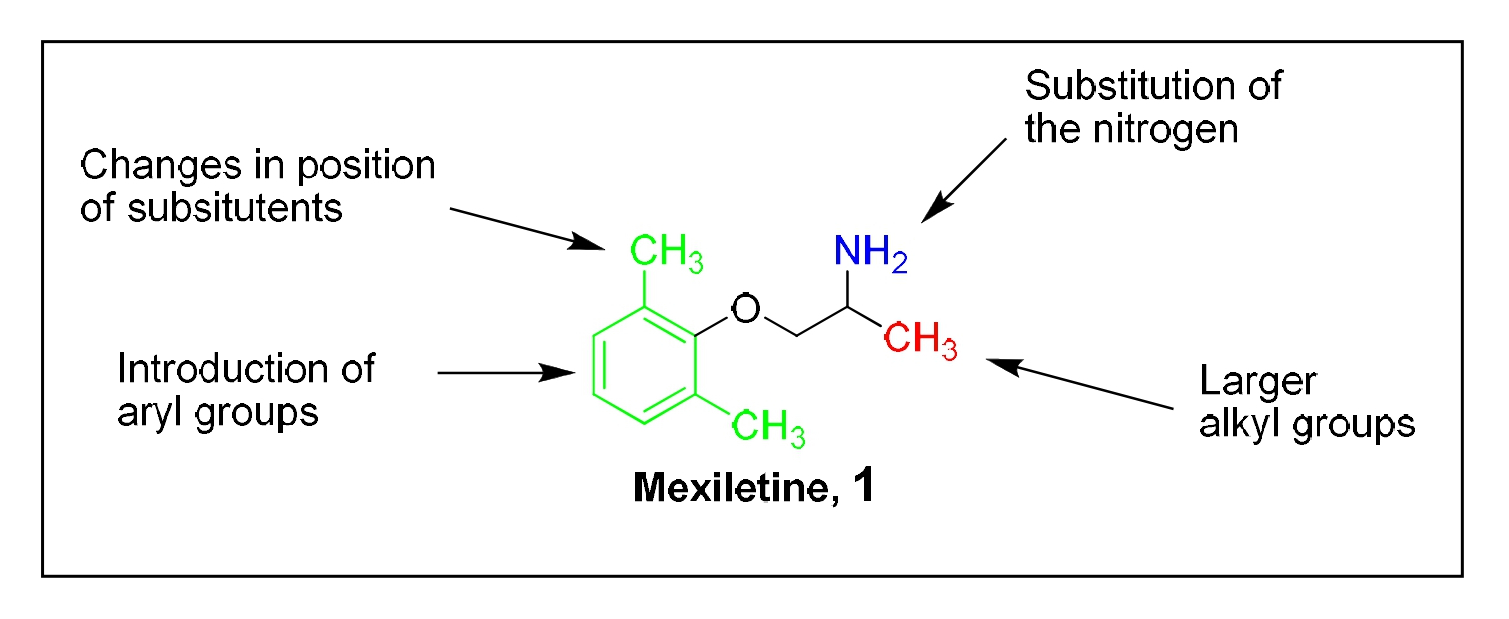

Mexiletine, 1 was re-engineered by chemical synthesis to afford analogs with increased on-target potency (i.e., sodium channel) and decreased off-target (i.e., potassium channel) effects [9]. The structure-activity relationship (SAR) for the effect of Mexiletine analogs on normal and hiPSC patient-derived cardiomyocytes was systematically evaluated in cardiomyocytes derived from an LQT3 patient (carrying the SCN5A F1473 mutation) and from an unrelated healthy donor [47]. Thus, the effects of Mexiletine analogs on cardiomyocytes with channelopathies (i.e., disease in a dish) were compared to the effects of compounds on normal non-pathogenic cardiomyocytes. To quantify the effect of modification of Mexiletine, the molecule was conceptually divided into three exploratory regions (Figure 1): (I) the region alpha to the primary amine moiety, (red), (II) the phenoxy region, (green) and (III) the N-substituted region, (blue).

Figure 1: Regions of Mexiletine chemically modified: Region I is alpha to the primary amine group, Region II is the phenoxy moiety (aryl group), Region III is substitution of the nitrogen.

Each compound was tested in dose-response studies in patient-derived hiPSC-CMs to determine a concentration of cessation of cell beating, an EC50 for shortening the action potential duration (APD), a fold-shortening of the APD and a concentration that caused shortening of the action potential. In normal cardiomyocytes, the concentration that caused cessation of cell beating, the concentration that caused pro-arrhythmic induction of EADs and the EC50 for shortening the APD were determined. In total, approximately 130 compounds were synthesized and tested [9]. Structural modifications of the portion of Mexiletine alpha to the primary amine (i.e., Region I) showed that an alpha aryl moiety showed greater fold-shortening than aliphatic substituents. However, partial aryl character (i.e., cyclopropyl compounds) were less effective at fold-shortening than aryl compounds. Modifications of the phenoxy moiety (i.e., Region II) resulted in compounds with potent APD shortening. N-Modification of selected compounds (Region III) yielded additional derivatives with potent fold-shortening and in some cases, less toxicity to cardiomyocytes. We also tested selected Mexiletine analogs in the aged rat heart perfusion model described above. Administration of H2O2 consistently promoted EADs and led to an incidence of aged fibrotic hearts to tachycardia and fibrillation. After administration to aged fibrotic hearts perfused with H2O2, certain Mexiletine analogs abrogated the EADs and returned the heart back to normal rhythm [9].

Deuterated analogs of mexiletine analogs

In in vitro metabolic studies, we observed the flavin-containing monooxyenase (FMO) [48] metabolized Mexiletine and analogs [10]. Surmising that metabolism was at the amine moiety, we incorporated a deuterium at the alpha carbon. Compared to non-deuterated compounds, incorporation of deuterium into phenyl Mexiletine analogs did not significantly alter the cardiovascular properties of the molecule but alpha deuteration of phenyl mexiletine and analogs improved pharmaceutical properties [10].

For certain Mexiletine analogs, alpha amino deuteration showed a significant increase in area under the curve (AUC) after administration to rats [10]. Development of drug analogs of Mexiletine with greater AUC and Cmax may allow fewer doses to patients. Frequent dosing and compliance with dosing is a major detriment to use of Mexiletine, especially in children. Also, compared to Mexiletine, side effects of seizures were observed decreased in phenyl Mexiletine classes of compound analogs examined due to the nature of the chemical structure. Phenyl mexiletines tested were observed to be considerably less CNS toxic compared to Mexiletine [9,10]. Improved pharmacokinetic properties of phenyl Mexiletines (e.g., deuterated phenyl Mexiletines) may afford the use of lower doses and be associated with less adverse drug interactions.

Pyridine analogs of mexiletine or phenyl mexiletine

We synthesized and tested approximately 30 pyridyl analogs of Mexiletine or phenyl Mexiletine [11]. For compounds examined, cell toxicity was dependent on the pyridyl substitution pattern of the compounds. For example, EADs were observed for 2-pyridyl phenyl Mexiletine and 4-pyridyl phenyl mexiletine. However, generally, from among 3-pyridyl phenyl Mexiletines tested, most did not produce EADs in normal cardiomyocytes [11]. We judged these compounds to be non-toxic because they did not cause cessation of beating or EADs in normal cardiomyocytes. Because Mexiletine can cause seizures in humans at elevated doses [49,50] examination of potential cell toxicity in human cardiomyocytes in a drug development campaign may be an efficient means of identifying untenable drug candidates.

Compared to Mexiletine, one synthetic pyridyl analog of Mexiletine was 22-fold more potent for the INa-L channel (i.e., 1.04 versus 22.5 µM) [11]. In addition, compared to Mexiletine, the analog was almost 5-fold more selective for the sodium versus the hERG channel (i.e., IC50 IKr/IC50 INa-L=2.4 and 11.2, respectively). Thus, from this study, a pyridyl analog of Mexiletine emerged as a potent INa-L channel inhibitor with good physiochemical properties. We concluded that synthesis and testing of pyridyl phenyl or other analogs of phenyl Mexiletine could lead to new chemotypes as potent and selective drug candidates to treat arrhythmias.

Conclusion

Although examples of the quantification of arrhythmia in hiPSC cardiomyocytes have been reported [51-53], including optogenetic methods [54,55], calcium sensitive probes [56] and voltage sensitive probes [56,57], our studies [9-12] were the first large scale, automated evaluation of synthetic analogs from iterative dynamic medicinal chemistry using patient-derived hiPSC cardiomyocytes. The approach facilitated rapid generation of physiologically relevant parameters useful in drug development. Our study was the first to use a voltage sensitive probe to characterize a patient-specific hiPSC cardiomyocyte disease model to show reversion of pathogenic disease phenotype with small molecule drug candidates in vitro. In summary, hiPSC cardiomyocyte technology in cardiovascular drug discovery and clinical management of heart disease is emerging as a viable method to test whether individual patient differences can predict clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to his collaborators and co-workers cited in the references herein.

Funding

We are grateful for the financial support of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) (Grant Number TR4-06857 to JRC). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of CIRM or any other agency of the State of California.

References

2. Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001 Oct 30;104(18):2158-63.

3. Koplan BA, Stevenson WG. Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2009 Mar 1; 84(3):289-297.

4. Fiedler LR, Chapman K, Xie M, Maifoshie E, Jenkins M, Golforoush PA, et al. MAP4K4 inhibition promotes survival of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and reduces infarct size in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2019 Apr 4;24(4):579-91.

5. Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science. 2014 Jul 18;345(6194):1247125.

6. Kretzschmar K, Clevers H. Organoids: modeling development and the stem cell niche in a dish. Developmental Cell. 2016 Sep 26;38(6):590-600.

7. Kumar D, Baligar P, Srivastav R, Narad P, Raj S, Tandon C, et al. Stem Cell Based Preclinical Drug Development and Toxicity Prediction. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2021 May 1;27(19):2237-51.

8. Strauss DG, Blinova K. Clinical trials in a dish. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2017 Jan 1;38(1):4-7.

9. Cashman JR, Ryan D, McKeithan WL, Okolotowicz K, Gomez-Galeno J, Johnson M, et al. Antiarrhythmic hit to lead refinement in a dish using patient-derived iPSC cardiomyocytes. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2021 May 4;64(9):5384-403.

10. Gomez‐Galeno J, Okolotowicz K, Johnson M, McKeithan WL, Mercola M, Cashman JR. Human‐induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes: Cardiovascular properties and metabolism and pharmacokinetics of deuterated mexiletine analogs. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 2021 Aug;9(4):e00828.

11. Johnson M, Gomez-Galeno J, Ryan D, Okolotowicz K, McKeithan WL, Sampson KJ, et al. Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and pyridyl-phenyl mexiletine analogs. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2021;46: 128162.

12. McKeithan WL, Savchenko A, Yu MS, Cerignoli F, Bruyneel AA, Price JH, et al. An automated platform for assessment of congenital and drug-induced arrhythmia with hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017 Oct 11;8:766.

13. Pfeiffer ER, Vega R, McDonough PM, Price JH, Whittaker R. Specific prediction of clinical QT prolongation by kinetic image cytometry in human stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2016 Sep 1;81:263-73.

14. Karagueuzian H, Pezhouman A, Angelini M, Olcese R. Enhanced late Na and Ca currents as effective antiarrhythmic drug targets. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017 Feb 6;8:36.

15. Liu G, Liu Z, Cao N. Human pluripotent stem cell–based cardiovascular disease modeling and drug discovery. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology. 2021 Jul;473(7):1087-97.

16. Fonoudi H, Ansari H, Abbasalizadeh S, Larijani MR, Kiani S, Hashemizadeh S, et al. A universal and robust integrated platform for the scalable production of human cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2015 Dec;4(12):1482-94.

17. Ribas J, Sadeghi H, Manbachi A, Leijten J, Brinegar K, Zhang YS, et al. Cardiovascular organ-on-a-chip platforms for drug discovery and development. Applied In Vitro Toxicology. 2016 Jun 1;2(2):82-96.

18. Lam CK, Wu JC. Clinical Trial in a Dish: Using Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Identify Risks of Drug-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2021 Mar;41(3):1019-31.

19. Huang J, Feng Q, Wang L, Zhou B. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac cells: application in disease modeling, cell therapy, and drug discovery. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021 Apr 1;9:735.

20. Apáti Á, Varga N, Berecz T, Erdei Z, Homolya L, Sarkadi B. Application of human pluripotent stem cells and pluripotent stem cell-derived cellular models for assessing drug toxicity. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2019 Jan 2;15(1):61-75.

21. Aboul-Soud MA, Alzahrani AJ, Mahmoud A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)—Roles in Regenerative Therapies, Disease Modelling and Drug Screening. Cells. 2021 Sep;10(9):2319.

22. Vaughan Williams EM. Classification of antiarrhythmic actions. In: Antiarrhythmic drugs. 1989. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

23. Weiss JN, Garfinkel A, Karagueuzian HS, Nguyen TP, Olcese R, Chen PS, et al. Perspective: a dynamics-based classification of ventricular arrhythmias. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2015 May 1;82:136-52.

24. Belardinelli L, Giles WR, Rajamani S, Karagueuzian HS, Shryock JC. Cardiac late Na+ current: proarrhythmic effects, roles in long QT syndromes, and pathological relationship to CaMKII and Oxidative Stress. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Feb 1;12(2):440-8.

25. Erickson JR, He BJ, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME. CaMKII in the cardiovascular system: sensing redox states. Physiological Reviews. 2011 Jul;91(3):889-915.

26. Bennett PB, Yazawa K, Makita N, George AL. Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 1995 Aug;376(6542):683-5.

27. Ulbricht W. Sodium channel inactivation: molecular determinants and modulation. Physiological Reviews. 2005 Oct;85(4):1271-301.

28. Antzelevitch C, Nesterenko V, Shryock JC, Rajamani S, Song Y, Belardinelli L. The role of late I Na in development of cardiac arrhythmias. Voltage Gated Sodium Channels. 2014:137-68.

29. Belardinelli L, Liu G, Smith-Maxwell C, Wang WQ, El-Bizri N, Hirakawa R, et al. A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of cardiac late sodium current suppresses experimental arrhythmias. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2013 Jan 1;344(1):23-32.

30. Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2007 Mar;9(3):219-27.

31. Ward CA, Giles WR. Ionic mechanism of the effects of hydrogen peroxide in rat ventricular myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1997 May 1;500(3):631-42.

32. Song Y, Shryock JC, Wagner S, Maier LS, Belardinelli L. Blocking late sodium current reduces hydrogen peroxide-induced arrhythmogenic activity and contractile dysfunction. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006 Jul 1;318(1):214-22.

33. Xie LH, Chen F, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN. Oxidative stress–induced afterdepolarizations and calmodulin kinase II signaling. Circulation Research. 2009 Jan 2;104(1):79-86.

34. Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Yao L, Fan P, Del Lungo M, Stillitano F, et al. Late sodium current inhibition reverses electromechanical dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013 Feb 5;127(5):575-84.

35. Isenberg G, Ravens U. The effects of the Anemonia sulcata toxin (ATX II) on membrane currents of isolated mammalian myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 1984 Dec 1;357(1):127-49.

36. Woosley RL, Funck-Brentano C. Overview of the clinical pharmacology of antiarrhythmic drugs. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1988 Jan 15;61(2):A61-9.

37. Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000 Oct 24;97(22):12329-33.

38. Qian JY, Guo L. Altered cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics in cultured Guinea pig cardiomyocytes as an in vitro model to identify potential cardiotoxicants. Toxicology in Vitro. 2010 Apr 1;24(3):960-72.

39. Kamath GS, Mittal S. The role of antiarrhythmic drug therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2008 May 1;50(6):439-48.

40. Morita N, Sovari AA, Xie Y, Fishbein MC, Mandel WJ, Garfinkel A, et al. Increased susceptibility of aged hearts to ventricular fibrillation during oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009 Nov;297(5):H1594-605.

41. Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, Peters RW, Obias-Manno D, Barker AH, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo: the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991 Mar 21;324(12):781-8.

42. Waldo AL, Camm AJ, DeRuyter H, Friedman PL, MacNeil DJ, Pitt B, et al. Survival with oral d-sotalol in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: rationale, design, and methods (the SWORD trial). The American Journal of Cardiology. 1995 May 15;75(15):1023-7.

43. Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Faragli A, Monteforte N, Bloise R, Memmi M, et al. Gene-Specific Therapy With Mexiletine Reduces Arrhythmic Events in Patients With Long QT Syndrome Type 3. Journal American College Cardiology. 2016;67: 1053-1058.

44. Wang DW, Kiyosue T, Sato T, Arita M. Comparison of the effects of class I anti-arrhythmic drugs, cibenzoline, mexiletine and flecainide, on the delayed rectifier K+ current of guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1996 May 1;28(5):893-903.

45. Mitcheson JS, Hancox JC. Modulation by mexiletine of action potentials, L-type Ca current and delayed rectifier K current recorded from isolated rabbit atrioventricular nodal myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 1997 Sep;434(6):855-8.

46. Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000 Oct 24;97(22):12329-33.

47. Terrenoire C, Wang K, Chan Tung KW, Chung WK, Pass RH, Lu JT, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells used to reveal drug actions in a long QT syndrome family with complex genetics. Journal of General Physiology. 2013 Jan;141(1):61-72.

48. Cashman JR, Motika M. Monoamine Oxidases and Flavin-Containing Monooxygenases. Comprehensive Toxicology. 2018; 10: 87-125.

49. Akıncı E, Yüzbaşıoglu Y, Coşkun F. Hemodialysis as an alternative treatment of mexiletine intoxication. The American Journal ofEmergency Medicine. 2011 Nov 1;29(9):1235-e5.

50. Roselli M, Carocci A, Budriesi R, Micucci M, Toma M, Mannelli LD, et al. Synthesis, antiarrhythmic activity, and toxicological evaluation of mexiletine analogues. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2016 Oct 4;121:300-7.

51. Guo L, Abrams RM, Babiarz JE, Cohen JD, Kameoka S, Sanders MJ, et al. Estimating the risk of drug-induced proarrhythmia using human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicological Sciences. 2011 Sep 1;123(1):281-9.

52. Gilchrist KH, Lewis GF, Gay EA, Sellgren KL, Grego S. High-throughput cardiac safety evaluation and multi-parameter arrhythmia profiling of cardiomyocytes using microelectrode arrays. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2015 Oct 15;288(2):249-57.

53. Navarrete EG, Liang P, Lan F, Sanchez-Freire V, Simmons C, Gong T, et al. Screening drug-induced arrhythmia using human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes and low-impedance microelectrode arrays. Circulation. 2013 Sep 10;128(11_suppl_1):S3-13.

54. Dempsey GT, Chaudhary KW, Atwater N, Nguyen C, Brown BS, McNeish JD, et al. Cardiotoxicity screening with simultaneous optogenetic pacing, voltage imaging and calcium imaging. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2016 Sep 1;81:240-50.

55. Klimas A, Ambrosi CM, Yu J, Williams JC, Bien H, Entcheva E. OptoDyCE as an automated system for high-throughput all-optical dynamic cardiac electrophysiology. Nature Communications. 2016;7: 11542.

56. Bedut S, Seminatore-Nole C, Lamamy V, Caignard S, Boutin JA, Nosjean O, et bal. High-throughput drug profiling with voltage-and calcium-sensitive fluorescent probes in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2016 Jul 1;311(1):H44-53.

57. Zeng H, Roman MI, Lis E, Lagrutta A, Sannajust F. Use of FDSS/ μCell imaging platform for preclinical cardiac electrophysiology safety screening of compounds in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2016 Sep 1;81:217-22.