Abstract

Background: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that is associated with local and systemic inflammation, resulting in chronic pain and physical function limitations that may negatively impact quality of life (QOL). Despite advances in pharmacological therapies, currently available treatment options may be associated with adverse events and come at a high price tag. As a result, research efforts have grown to focus on nutritional interventions to support pharmacological therapies, reduce inflammation (targeting biomarkers of disease activity) and improve QOL.

Objectives: In this systematic review, data was collected on the most recent non-pharmacological interventions used for RA management. The efficacy, safety, and potential practical applications of various nutritional interventions used in the RA management will be discussed. This review has been divided into three parts. In the last section of our 3-part series we will discuss interventions involving fruits and herbs and their clinical impact on patients with RA. The compounds discussed in this article include cranberry juice, curcumin, garlic, ginger, pomegranate, saffron, and sesamin. For more information on the other contents of this systematic review you may refer back to Part 1: Dieting and Part 2: Supplementation.

Methods: A search of the literature was conducted to identify nutritional interventions in the progression and management of RA. Eligible study designs included meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized control trials (RCT), and prospective/retrospective studies. Exclusion criteria included non, in vivo human studies, n<40, cross-sectional studies, case-studies, and lack of access to available text.

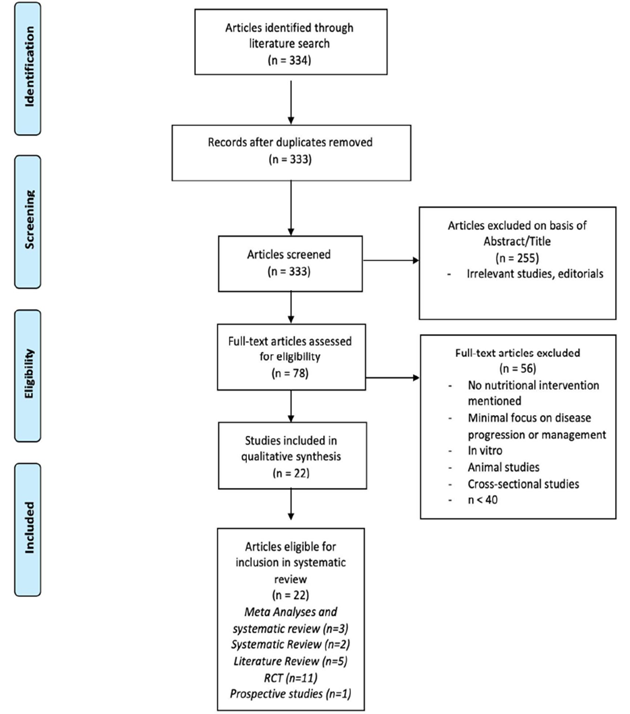

Results: Initially, 334 articles were identified. After removing studies for lack of relevance, exclusion criteria and duplicates, 22 articles remained. The eligible articles were divided into five groups based on design: Meta analyses, systematic reviews, RCTs, literature reviews, and prospective studies. The eligible articles were grouped together based on intervention type: diets, supplementation and the implementation of fruits and herbs. Seven articles were placed under the category of fruits and herbs which includes six RCTs and one literature review.

Conclusion: Dietary interventions may be an effective method for reducing inflammation and symptoms associated with RA. Several studies showed that dietary interventions improved various markers of disease activity, symptomatology, with minimal adverse event risk. Still, most nutritional remedies studied require further research effort before they can be confidently recommended as alternative therapies. These remedies include cranberry juice, garlic, ginger, pomegranate extract, saffron, and sesamin. All of these remedies with the exception of garlic, improved DAS-28 scores. Curcumin was the only compound that lacked sufficient evidence to justify a recommendation. Clinical practitioners can use these remedies in their treatment algorithms without specific recommendations on dosing and use, as nearly all present with minimal risk.

Keywords

Arthritis, Intervention, Nutrition, Review, Rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a complex autoimmune disease that is characterized by systemic inflammation. RA is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis and is more likely to affect woman than men [1-3]. Symptoms include joint stiffness, swelling, fatigue and decreased quality of life. The pathophysiology of RA is not fully understood. Disruptions in intercellular pathways are believed to contribute to the autoimmune response as well as increased inflammation [2]. The autoimmune response and complex inflammation processes lead to joint damage, bone erosion, synovitis, and cartilage degradation. Individuals suffering from RA are more susceptible to cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal issues, pulmonary disease, and mental health problems [3]. The exact cause of RA remains unclear. However, research suggests a combination of environmental, genetic and lifestyle factors leading to the onset of disease [2]. Traditionally, pharmacological therapies are used to treat swelling, joint pain, and slow disease progression. Without a permanent cure, complimentary therapies are often utilized to offset the unpleasant side effects of medications. Popular alternative therapies include dietary supplements, anti-inflammatory diets, acupuncture, and massage [1,3]. Research suggest that lifestyle factors and diet may be effective at lowering disease activity thus increasing quality of life and RA outcomes.

Previous studies have indicated that various bioactive compounds found in foods may suppress production of inflammatory cytokines and reduce disease activity, thereby, aiding in RA treatment. These include curcumin (a compound found in turmeric), ginger, pomegranate, garlic, saffron, sesamin, and cranberries. In addition to medication, incorporating these foods into the diet may help RA patients reduce symptoms. This article provides a systematic review of currently available data on the use of non-pharmaceutical interventions for RA management, which was published between 2017 and 2020. The objective is to provide clinicians information on the safety and effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions in RA management to aid in their recommendations. These recommendations include whether these non-pharmaceutical approaches used in combination with or alternatively to pharmaceutical agents.

In this effort, standardized assessments have been developed to ascertain both subjective and objective clinical improvements in disease activity. The Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS-28) has been used to monitor disease progression and assesses tender joint counts (TJC), swollen joint counts (SJC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and a global health rating. The 36 item Short Form health survey (SF 36) is a subjective questionnaire utilized for gauging QOL. The visual analog scale (VAS) is an instrument used to measure subjective pain ratings by selecting a value from 0 (no pain) to 100 (severe pain). The health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) is a tool utilized for self-report of functional status. Additionally, the Ritchie score is a tool that is used to monitor disease severity. This score evaluates the tenderness of joint groups and scores them on a scale from zero to three. These indices will be used because they emphasize the role of both pain and function and can provide clinicians a means of understanding the impact of these treatments on disease status.

Our original search included over 22 articles which were then subsequently divided into three sections, Dieting, Supplementation, and Fruits and herbs. In the last of our 3-part series we will discuss interventions involving fruits and herbs and their clinical impact on patients with RA. The compounds discussed in this article include cranberry juice, curcumin, garlic, ginger, pomegranate, saffron, and sesamin. For more information on the other contents of this systematic review you may refer back to Part 1: Dieting [4] and Part 2: Supplementation [5].

Methods

Search strategy

A computer assisted systematic literature review was performed using PubMed for research articles examining nutritional interventions in the progression and management of RA. The PubMed word search included “Rheumatoid Arthritis Nutrition”, filtering for articles published between 2017 and 2020. The reference lists of retrieved articles were also considered when found to be relevant and if they fit the search criteria but were not discovered through individual searches. Relevance of these articles were assessed through a hierarchical approach that evaluated first the title, followed by the abstract, and the full manuscript. For articles that were not freely available, access was gained through the use of Nova Southeastern University (NSU) library resources.

Selection criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they discussed specific nutritional interventions evaluating the management or progression of active RA defined by criteria by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or European League Against Rheumatism [6]. Eligible study designs included meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized control trials (RCT), and prospective/retrospective studies. Exclusion criteria included non in vivo human studies, n<40, cross-sectional studies, case-studies, and lack of access to available text. A flow diagram

Search strategy

A computer assisted systematic literature review was performed using PubMed for research articles examining nutritional interventions in the progression and management of RA. The PubMed word search included “Rheumatoid Arthritis Nutrition”, filtering for articles published between 2017 and 2020. The reference lists of retrieved articles were also considered when found to be relevant and if they fit the search criteria but were not discovered through individual searches. Relevance of these articles were assessed through a hierarchical approach that evaluated first the title, followed by the abstract, and the full manuscript. For articles that were not freely available, access was gained through the use of Nova Southeastern University (NSU) library resources.

Selection criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they discussed specific nutritional interventions evaluating the management or progression of active RA defined by criteria by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or European League Against Rheumatism [6]. Eligible study designs included meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized control trials (RCT), and prospective/retrospective studies. Exclusion criteria included non in vivo human studies, n<40, cross-sectional studies, case-studies, and lack of access to available text. A flow diagram (Figure 1) was developed using the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) 2009 outline [7].

Figure 1: Selection process flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Based on study design, studies were divided into five groups:

Meta Analyses: 3

Systematic review: 2

RCT: 11

Literature reviews: 5

Prospective study: 1.

Results

A total of 334 articles were identified from the initial electronic database search. Two hundred fifty-five articles were excluded based on lack of relevance found during title and abstract screening, and one duplicate was removed. Of the remaining 78 articles, 56 were excluded for the following reasons (based on exclusion criteria): Lack of in vivo human models, n<40, and lack of significant interventional study. A total of 22 articles remained for inclusion in this review.

|

Study |

Publication Year

|

Subjects |

Intervention(s) - duration |

Significant improvements |

|

Cranberry Juice Decreases Disease Activity in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis - Thimóteo et al. [11] |

2018 |

41 |

Cranberry juice

|

Compared to baseline:

Anti-CCP (p=0.034) Blood Glucose (p=0.04) DAS-28 (p=0.048)

|

|

Effect of Curcumin Nanomicelle on the Clinical Symptoms of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial - Javadi et al. [14]

|

2019 |

65 |

Curcumin

|

Compared to baseline:

DAS-28 (p=0) SJC (p=0.008) TJC(p=0.001) |

|

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Garlic Supplement Effects on Some Serum Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress, and Quality of Life in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis - Moosavian et al. [19]

|

2020 |

62 |

Garlic

|

Compared to placebo:

HAQ (p=0.026) MDA (p=0.032) TAC (p=0.026) VAS (p<0.001)

|

|

The Effect of Ginger Supplementation on Some Immunity and Inflammation Intermediate Genes Expression in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis - Aryaeian et al. [21]

|

2017 |

63 |

Ginger

|

Compared to placebo:

DAS-28 (p=.003) FoxP3 gene (p<.05) T-bet gene (p=.045) |

|

Dietary Fruits and arthritis – Basu et al. [34]

|

2017 |

55 |

Pomegranate

|

Compared to placebo:

DAS-28 (p<0.001) EMS (p=0.004) ESR (p=0.003) Glutathione Peroxidase (p<0.001) HAQ (p=0.007) SJC (p<0.001) TJC (p=0.001) VAS (p=0.003)

|

|

The Effect of Saffron Supplement on Clinical Outcomes and Metabolic Profiles in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial - Hamidi et al. [42]

|

2020 |

66 |

Saffron

|

Compared to placebo:

hs-CRP (p=0.004) DAS-28 (p ≤ 0.001) ESR (p=0.03) PGA (p =.007) SJC (p<0.001) TJC (p=0.001) VAS (p=0.003)

Compared to baseline:

IFN-γ (p=0.037)

|

|

A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial, Evaluating the Sesamin Supplement Effects on Proteolytic Enzymes, Inflammatory Markers, and Clinical Indices in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis - Helli et al. [45]

|

2019 |

44 |

Sesamin

|

Compared to placebo:

COX-2 (p=0.071) hs-CRP (p=0.033) DAS-28 (p=0.09) Hyaluronidase P=0.003) Matrix MMP-3 (P=0.003) TNF-α (p=0.047) VAS (p=0.025)

|

Discussion

Cranberry Juice

Cranberry juice decreases disease activity in women with RA: RA is characterized by autoimmune activation of leukocytes that increase cytokine release, inflammatory response, and oxidative stress. Clinical research suggests that dietary intake of antioxidants can mediate the inflammatory response and oxidative stress seen in RA patients and improve symptomatology [8]. Specifically, berries are rich in antioxidants and have been shown to improve various biomarkers of disease activity [9]. In addition, a few studies have demonstrated that cranberries have been associated with lower serum lipid levels, decreases in blood pressure, and improvements in inflammatory biomarkers [10]. Based on the benefits of consuming foods rich in antioxidants, it has been suggested that regular consumption of cranberry juice may improve the inflammatory response and symptomatology tied to RA. In a study by Thimóteo et al., the investigators evaluated the effects of drinking cranberry juice in 41 participants with RA, in which participants were instructed not to make any changes to their diet, medication, and current physical activity levels [11]. Participants (n=18) in the control group were asked to follow their normal dietary routine. Participants (n=23) in the intervention group were asked to consume 500 mL/d of reduced-calorie cranberry juice in addition to their daily diet, medication, and physical activity regimens. Anthropometric and lab analysis were conducted at the beginning of the study and the conclusion of the study. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triacylglycerol, and glucose levels were evaluated by a biochemical autoanalyzer. White blood cell (WBC), platelet, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) counts were determined using hematologic autoanalyzers. Serum c-reactive protein (CRP) levels and rheumatoid factor (RF) titers were measured using a turbidimetric assay. Serum ferritin levels, anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies, and total plasma levels of homocysteine, were determined with chemiluminescent microparticle assays. Results of the study indicated that those in the intervention group demonstrated decreases in DAS-28 (p=0.048) and anti-CCP (p=0.034) after 90 days of treatment as compared to baseline. The control group experienced little to no change from baseline to the end of the study. whereas changes in inflammatory biomarkers were not found in either group. Statistically significant decreases in blood glucose were also seen in the intervention group (p=0.04). Criticisms of this study included having a small sample size, despite statistical significance observed. Participant’s dietary intake was not assessed to rule out any effects caused by diet rather than cranberry juice, which may have confounded the data. Storage and storage temperatures may also affect polyphenol content in juices thus lowering the antioxidant benefit associated with cranberry juice boxes and was not specifically addressed in the study [12]. One concern of 500 mL/d of reduced calorie cranberry juice implementation would be the application in a population with impairments in fasting glucose, however, the results of the study indicated there were statistically significant decreases in blood glucose thus indicating that would not be the case. Due to the large amount needed for daily consumption, it may not be reasonable to expect patients to maintain dietary supplementation with cranberry juice for long periods of time, however, incorporation into the diet has minimal risk and thus the benefits should be emphasized to this patient population.

Curcumin

Effect of curcumin nanomicelle on the clinical symptoms of patients with RA: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: Curcumin is a polyphenol that is typically found in the rhizomatous spice, turmeric. The medicinal properties of turmeric are well understood and more recently, research efforts have aimed at evaluating curcumin’s mechanisms and effects [13]. Curcumin has been shown to demonstrate anti-inflammatory effects in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes. In animal studies (mouse model), curcumin has shown anti-arthritic effects and reduced incidence of liver toxicity when combined with methotrexate. In addition, the combination of curcumin and prednisolone demonstrated enhanced effects, indicating a potential role in the management of RA patients. In 2019, a clinical study conducted by Javadi et al. assessed the effects of 120 mg/day of curcumin nanomicelle among RA patients over a 12-week period [14]. The results indicated statistically significant improvements in the DAS-28, tender joint count (TJC) as well as swollen joint count (SJC) when compared to baseline, but these findings were not significant when compared to placebo (likely attributable to the low dose of curcumin used in the study). The investigators reference two prior studies that utilized up to 1,000 mg/day of curcumin and reported significant findings as compared to placebo. These studies were not included in this review because did not meet the inclusion criteria of n>40. For dosage comparison, other studies utilizing curcumin in multiple myeloma patients have indicated doses of up to 12,000 mg/day with excellent safety and tolerability, thus further suggesting the relevancy of utilizing sufficient doses [15]. Based on this information, there is not sufficient data to indicate that 120 mg/d of curcumin would result in any clinical improvements as compared to placebo. Still, when considering the vast applications on various diseases and the excellent safety profile it is recommended that further studies be performed at higher doses before formal recommendations can be made regarding the efficacy of curcumin in RA.

Garlic

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, evaluating the garlic supplement effects on some serum biomarkers of oxidative stress, and QOL in women with RA: Garlic is an herb of the Alliacea family, which has been used for food consumption and medicinal purposes. Growing research efforts have highlighted its anti-diabetic, cardioprotective, and anti-inflammatory properties [16]. Researchers have illustrated garlic’s antioxidative effects in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Garlic is also being considered as an alternative to current anti-arthritic agents [17,18]. Moosavian et al. studied the effects of 500 mg of dried garlic powder tablets (equivalent to 2500 mg of garlic, containing 2.5 mg allicin) in comparison to starch placebos in 62 women with RA [19]. The study participants were instructed to take the tablets (either garlic powder tablets or starch placebos) twice per day over an eight-week period equating to 1000 mg/day among those taking the garlic powder tablets. Placebo tablets were similar in terms of appearance and before the intervention the placebo tablets were placed near the garlic tablets in order to transfer the smell. Both patients and investigators were blinded to allocation of the tablets. Garlic consumption as part of a normal diet was banned throughout the duration of the study. Compliance was assessed by counting the numbers of tablets consumed during the study and patients who consumed less than 90 percent were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included smoking, medication changes, consuming antioxidants, and omega 3 fatty acids 4 weeks prior to the study and those taking hormone replacement therapy or anticoagulants. A limited range of blood antioxidant markers were tested due to financial limitations as well as synovial biomarkers were not tested due to ethical limitations.

The investigators found that serum total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (p=0.2 to 0.032) significantly increased, whereas malondialdehyde (MDA) (p=<0.001), a marker for oxidative stress, was significantly lower among those who consumed garlic as compared to placebo. Significant decreases in pain after activity were observed, as measured by a visual analog scale (VAS) (p<0.001), in the garlic group when compared to placebo. In addition, statistically significant improvements (p<0.001) were reported in quality of life in the garlic group as compared to placebo. The health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) was used to measure quality of life. The author postulated that the effects of garlic on TAC may occur through increasing intracellular antioxidants such as glutathione, uric acid, and bilirubin as well as by upregulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes. Based on these findings, it appears that recommendations of 1000 mg/day of garlic tablets for eight weeks has the capability to improve markers of oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, and clinical indicators of pain in female RA patients. Although there are clear benefits observed in this study, the investigators believe more trials are required in order to determine the efficacy of garlic in the patient population studied. With garlic’s excellent safety profile and the relatively simplistic means of incorporating it into one’s diet, clinicians should discuss the potential benefits of its implementation with their patients.

Ginger

The effect of ginger supplementation on some immunity and inflammation intermediate gene expression in patients with active RA: Ginger is a plant from the Zingiberaceae family that is often consumed for its medicinal benefits. Ginger has been shown to have anti-emetic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diabetic properties [20,21]. It has also been shown to relieve stiffness and pain in individuals with osteoarthritis. Meanwhile, there is little data on the efficacy of its use in RA [22]. In one study, Aryaeian et al. performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial with 63 RA patients to evaluate the effect of ginger power as compared to placebo for a period of 12 weeks [23]. Patients were randomly assigned into two groups (1500 mg/day of ginger powder or placebo containing fried wheat powder). Placebos were of similar appearance and odor, as they had spent two weeks in a ginger powder box prior to transmit the smell. Investigators and patients were blinded to study groups. This study is unique in that it focused on gene expression to evaluate the effects of ginger consumption. FoxP3 is a gene that functions to regulate the pathways pertaining to the body’s immune response. Statistically significant increases in FoxP3 gene expression were observed in the intervention group when compared to the control (p<0.05). Increases in the FoxP3 gene, such as those observed in the study, are thought to aid in the prevention of autoimmune disorders [24]. PPAR- γ is another gene that may be used as an indicator of disease activity and treatment efficacy due to its anti-inflammatory characteristics [25,26]. PPAR-γ agonists have been shown to inhibit translation of genes such as TNF- alpha and IL-1 implicated in joint inflammation [27] and have demonstrated anti-inflammatory characteristics on the activity of RA in experimental models [28]. This study demonstrated significant increases in PPAR-γ from baseline (p<0.05), however, when compared to controls there was no significant difference found (p=0.12). Additionally, expression of T-bet gene decreased significantly among those who received ginger (p=0.045). T-bet gene is a transcription factor that induces proliferation of Th1 and is essential in the production of IFN-γ, a cytokine crucial in the triggering of immune responses [27,28]. Therefore, the reduction of T-bet expression may demonstrate some of the anti-inflammatory properties of ginger. Further results indicated a significant reduction of DAS-28 among those who received ginger as compared to placebo (p=0.003). Although there are many genetic indications that ginger may result in anti-inflammatory changes in RA patients, more trials are required in order to determine the efficacy of its application. This appears to be one of the first studies to investigate the application of ginger in RA patients. Currently, we are unable to recommend its supplementation within clinical practice. Yet, ginger has been shown to be a safe ingredient that is well tolerated up to 2 grams/day [22] and thus there is minimal risk in incorporating it into one’s diet.

Pomegranate

Dietary fruits and arthritis - Pomegranate extract alleviates disease activity and some blood biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in RA patients: Pomegranate is a nutritious fruit that contains various vitamins, flavonoids and immune-boosting antioxidants [29]. Pomegranate’s antioxidant properties have been attributed to its polyphenol content and functions through its inhibition of various enzymes such as cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) and nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) [30-32]. Products and extracts from this fruit have been shown to have antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective properties and thus mechanistically has the potential to benefit patients with RA [33]. In a review conducted by Basu et al., one of two studies discussed were found to meet our inclusion criteria [34]. In the study from Basu’s review, Gahvipour et al. examined the effects of two 250 mg capsules/d of POMx (pomegranate extract standardized to 40 percent ellagic acid) compared to cellulose placebo over eight weeks [35]. The investigators found statistically significant decreases in DAS-28 score (p<0.001), pain intensity (p=0.003), ESR (p=0.03), HAQ score (p=0.007), SJC (p=<0.001) and TJC (p=0.001). Glutathione peroxidase concentration was also seen to be significantly elevated in those who received POMx compared to placebo. No adverse effects were reported throughout the duration of the study. Overall, the data evaluated is in favor of pomegranate extract resulting in both clinical improvements and improvements in biomarkers of disease activity. The investigators reference another 12-week study performed by Balbir-Gurman evaluating POMx consumption and reported no serious adverse events among the six study participants [36]. Pomegranate fruit consumption appears promising, but further research is needed to determine the efficacy, safety, and dosage over longer periods of time. It is reasonable, based on the study outcomes and limited adverse event profile, for clinicians to discuss with their patients the potential benefits of adding pomegranate fruit to their diet.

Saffron

The effect of saffron supplement on clinical outcomes and metabolic profiles in patients with active RA: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial: Saffron is a spice derived from the Crocus sativus flower, which is primarily cultivated in Iran, Spain, India, and Greece. Saffron is considered an antioxidant, with anti-inflammatory properties that are accomplish by inhibition of the cyclooxygenase pathway [37,38]. Animal studies have demonstrated that use of saffron may reduce inflammatory interleukins and decrease chronic and acute pain. [39-41]. Hamidi et al. performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, in which participants received 100 mg of saffron per day (in tablet form) or cellulose placebo (similar in appearance to saffron tablet) over a three-month period [42]. The investigators demonstrated significant improvements in TJC, SJC, patient global assessment, pain intensity, and DAS-28 among those who received the saffron tablets as compared to placebo. Significant decreases in IFN-γ, hs-CRP, and ESR were also seen among those who received the saffron tablets. The investigators highlighted several limitations of their study including lack of facilities to measure additional inflammatory and oxidative markers, recruiting only female participants, and having a small sample size.

The findings from the study suggest that the administration of 100 mg/day for 12 weeks may result in clinical benefits in RA patients. This was demonstrated with significant improvements in the DAS-28 and pain intensity as well as reductions in inflammatory markers. With no adverse events reported by patients we can assume this dosage for the observed time frame is safe for supplementation. However, little is known about the dosing of saffron or the effects of long-term supplementation. Therefore, before specific recommendations can be made, further clinical trials should be performed.

Sesamin

A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, evaluating the sesamin supplement effects on proteolytic enzymes, inflammatory markers, and clinical indices in women with RA: RA patients suffer from pain commonly caused by the presence of chronic inflammation, which remains the target of management approaches. Seasamin, a lignan derived from sesame oil, has a history of use in Asian cultures. Bioactive compounds in Sesamin are believed to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Animal studies have demonstrated the ability of sesamin to suppress NF-κB, an important enzyme in oxidative and inflammatory pathways. Inhibition of this enzyme can reduce the inflammatory response downstream [43,44]. Seasmin is thought to protect cartilage degradation, which can be beneficial in RA treatment. The aforementioned properties suggest that sesamin supplementation could be effective in treating RA symptoms. In one study, Helli et al. examined the effect of seasmin supplementation on proteolytic enzymes, which are inflammatory markers and clinical indices associated with RA [45]. The patients were divided into two groups: intervention (sesamin capsules (200 mg/d, one capsule per day) and control (placebo capsules that include 200 mg of starch). Subjects were assigned to either group by randomized block allocation according to Body Mass Index (BMI) and provided either intervention or control for six weeks. Clinical assessment was evaluated based on DAS-28, SJC/TJC and VAS. Serum levels of proteolytic enzymes (hyaluronidase, aggrecanase, and MMP?3) and inflammatory biomarkers (hs?CRP, IL?1β, IL?6, TNF?α, and COX-2) were measured at the beginning and end of the study. Statistically significant decreases were observed in the intervention group for inflammatory biomarkers hs?CRP (p=0.033), TNF?α (p=0.047), and COX?2 (p=0.071). Only the intervention group experienced a decrease in hyaluronidase and MMP?3 (P=0.003). Participants in the intervention group also had lower DAS-28 scores at the end of the study, however, they did not reach statistical significance before ANCOVA adjustment. Neither SJC nor TJC demonstrated significant improvements before adjustment, although, there was significant improvements seen in the VAS score. This study suggests that seasmin supplementation is effective in relieving pain associated with RA symptoms and related inflammatory biomarkers. The major drawback of this study was the inability to measure sesamin concentration due to insufficient budget and short study duration. Due to individual differences in absorption and digestions, measuring concentration levels would have aided in determining effective dosages.

This study demonstrated that supplementation of 200 mg/day of sesamin for six weeks resulted in significant reductions in enzymes understood to contribute to cartilage and bone degradation [45]. In addition, supplementation was associated with significant clinical improvement (DAS-28 improvement), indicating the potential to aid in RA patient management. Still, based on the lack of information regarding dosing, proposed mechanisms and other human studies, more research is needed before safe recommendations can be made.

Conclusion

This review provided insight into the most recent data on different, non-pharmacologic interventions for the management of RA patients. It was the goal of this review to detect clinical improvements utilizing these interventions, which could serve as a tool for clinicians to confidently recommend these interventions to their patients and provide their patients with information to aid in making decision on incorporating these agents into their treatment algorithms. The review included evaluating of Cranberry juice (500 ml/d) [11], garlic (1000 mg/d) [19], ginger (1500 mg/d) [21], pomegranate extract (500 mg/d) [35], saffron (100 mg/d) [42], and sesamin (200 mg/d) [45], in which study results found all interventions provided significant clinical improvements when compared to placebo in RA patients. All of these studies had excellent safety profiles in addition to their clinical benefits but lacked the sufficient previous research for us to confidently make a clinical recommendation. Still, many of these compounds can be easily incorporated into one’s diet (Cranberry juice, Garlic, Ginger, Pomegranates) with minimal risk and thus the benefits should be discussed with patients. Below is a brief summary of the clinical improvements seen in these trials (see below). While nearly all interventions studied in this review provided significant clinical findings, curcumin (120 mg/d) lacked sufficient data for recommendations [14] and further trials at higher doses may be required to uncover significant findings.

|

|

DAS-28 |

SJC/TJC |

VAS |

HAQ |

|

Cranberry juice (b) |

? |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

Curcumin (b) |

??? |

??? |

No data |

No data |

|

Garlic (p) |

No data |

No data |

??? |

?? |

|

Ginger (p) |

??? |

No data |

No data |

No data |

|

POMx (p) |

??? |

??? |

??? |

??? |

|

Saffron (p) |

??? |

??? |

??? |

No data |

|

Sesamin (p) |

Non-significant |

Non-significant |

?? |

No data |

|

*(b) = compared to baseline; (p) = compared to placebo |

||||

In conclusion, we encourage clinical practitioners to utilize this review as a tool to guide their use of these non-pharmacologic agents in RA management. With the evidence presented, we recommend that clinical practitioners use their judgement in implementing these interventions in the algorithms of RA patients most likely to benefit.

Author Contributions

AM and KB performed the systematic review. MK validated the systematic search. AM, KB and CE wrote the paper. This review paper was conceptualized and reviewed by AM and MK as part of ongoing projects in the NSU Rheumatology Research Unit. Beth Gilbert from Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University served as the primary editor for the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest: All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Articles and Interventions Discussed in Previous Sections

Part 1: Dieting: ADIRA, Elimination/Elemental Diets, Vegetable/Vegan diets, Weight Loss, and Mediterranean diets

1) Anti-inflammatory Diet In Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADIRA)-a Randomized, Controlled Crossover Trial Indicating Effects on Disease Activity - Vadell et al. [46]

2) Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis with Dietary Interventions - Khanna et al. [47]

3) Nutrition Interventions in Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Potential Use of Plant-Based Diets. A Review – Alwarith et al. [48]

4) The effects of the Mediterranean diet on rheumatoid arthritis prevention and treatment: a systematic review of human prospective studies -Forsynth et al. [49]

5) Effect of a Dynamic Exercise Program in Combination With Mediterranean Diet on Quality of Life in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis - Garcia-Morales et al. [50]

Part 2: Supplementation: Coenzyme q10, Synbiotics, Probiotics, GLA, N-3 PUFA, Marine oil, and Quercetin

1) Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Matrix Metalloproteinases and DAS-28 in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial - Nachvack et al. [51]

2) Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis With Dietary Interventions - Khanna et al. [47]

3) Clinical Benefits of n-3 PUFA and ?-Linolenic Acid in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis - Veselinovic et al. [52]

4) Marine Oil Supplements for Arthritis Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials - Senftleber et. al. [53]

5) The Mediterranean Diet, Fish Oil Supplements and Rheumatoid Arthritis Outcomes: Evidence From Clinical Trials - Petersson et al. [54]

6) Intake of ω-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis - Gioxari et al [55]

7) Effect of ω-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Arthritic Pain: A Systematic Review - Abdulrazaq et al. [56]

8) The Effect of Quercetin on Inflammatory Factors and Clinical Symptoms in Women With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial - Javadi et al. [57]

9) Synbiotic Supplementation and the Effects on Clinical and Metabolic Responses in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial - Zamani et al. [58]

10) The efficacy of probiotic supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta?analysis of randomized, controlled trials - Aqaeinezhad Rudbane et al. [59].

References

2. Gibofsky A. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis: A Synopsis. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2014 May;20(7 Suppl):S128-35.

3. Hyndman IJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: past, present and future approaches to treating the disease. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2017 Apr;20(4):417-9.

4. Marquez AM, Evans C, Boltson K, Kesselman M. Nutritional Interventions and Supplementation for Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Systematic Review for Clinical Application, Part 1: Dieting. Curr Rheumatol Res 2020. 1(2):17-26.

5. Marquez AM, Evans C, Boltson K, Kesselman M. Nutritional interventions and supplementation for rheumatoid arthritis patients: A systematic review for clinical application, Part 2: Supplementation. Curr Rheumatol Res 2020. 1(2):27-38.

6. Kay J, Upchurch KS. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology. 2012 Dec 1;51(suppl_6):vi5-9.

7. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097.

8. Pattison DJ, Harrison RA, Symmons DP. The role of diet in susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2004 Jul 1;31(7):1310-9.

9. Basu A, Lyons TJ. Berries in the nutritional management of metabolic syndrome. InNutritional Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome 2015 Sep 18 (pp. 362-369). CRC Press.

10. Novotny JA, Baer DJ, Khoo C, Gebauer SK, Charron CS. Cranberry juice consumption lowers markers of cardiometabolic risk, including blood pressure and circulating C-reactive protein, triglyceride, and glucose concentrations in adults. The Journal of Nutrition. 2015 Jun 1;145(6):1185-93.

11. Thimóteo NS, Iryioda TM, Alfieri DF, Rego BE, Scavuzzi BM, Fatel E, et al. Cranberry juice decreases disease activity in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2019 Apr 1;60:112-7.

12. Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004 May 1;79(5):727-47.

13. Hewlings SJ, Kalman DS. Curcumin: a review of its’ effects on human health. Foods. 2017 Oct;6(10):92.

14. Javadi M, Khadem Haghighian H, Goodarzy S, Abbasi M, Nassiri‐Asl M. Effect of curcumin nanomicelle on the clinical symptoms of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double‐blind, controlled trial. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2019 Oct;22(10):1857-62.

15. Lao CD, Ruffin MT, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM, et al. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006 Dec;6(1):1-4.

16. Tsai CW, Chen HW, Sheen LY, Lii CK. Garlic: Health benefits and actions. BioMedicine (Netherlands).

17. Rana SV, Pal R, Vaiphei K, Sharma SK, Ola RP. Garlic in health and disease. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2011 Jun;24(1):60-71.

18. Shang A, Cao SY, Xu XY, Gan RY, Tang GY, Corke H, et al. Bioactive compounds and biological functions of garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods. 2019 Jul;8(7):246.

19. Moosavian SP, Paknahad Z, Habibagahi Z. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial, evaluating the garlic supplement effects on some serum biomarkers of oxidative stress, and quality of life in women with rheumatoid arthritis. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2020 Jul;74(7):e13498.

20. Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008 Feb 1;46(2):409-20.

21. Aryaeian N, Tavakkoli H. Ginger and its effects on inflammatory diseases. Advances In Food Technology And Nutritional Sciences. 2015;1(4):97-101.

22. Gregory PJ, Sperry M, Wilson AF. Dietary supplements for osteoarthritis. American Family Physician. 2008 Jan 15;77(2):177-84.

23. Aryaeian N, Shahram F, Mahmoudi M, Tavakoli H, Yousefi B, Arablou T, et al. The effect of ginger supplementation on some immunity and inflammation intermediate genes expression in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Gene. 2019 May 25;698:179-85.

24. Palma A, Sainaghi PP, Amoruso A, Fresu LG, Avanzi G, Pirisi M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression in monocytes/macrophages from rheumatoid arthritis patients: relation to disease activity and therapy efficacy—a pilot study. Rheumatology. 2012 Nov 1;51(11):1942-52.

25. Shahin D, Toraby EE, Abdel-Malek H, Boshra V, Elsamanoudy AZ, Shaheen D, et al. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist (pioglitazone) and methotrexate on disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (experimental and clinical study). Clinical Medicine Insights: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2011 Jan;4:CMAMD-S5951.

26. Nammi S, Sreemantula S, Roufogalis BD. Protective effects of ethanolic extract of Zingiber officinale rhizome on the development of metabolic syndrome in high‐fat diet‐fed rats. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2009 May;104(5):366-73.

27. Nammi S, Sreemantula S, Roufogalis BD. Protective effects of ethanolic extract of Zingiber officinale rhizome on the development of metabolic syndrome in high‐fat diet‐fed rats. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2009 May;104(5):366-73.

28. Nazari B, Amirzargar A, Nikbin B, Nafar M, Ahmadpour P, Einollahi B, et al. Comparison of the Th1, IFN-γ secreting cells and FoxP3 expression between patients with stable graft function and acute rejection post kidney transplantation. Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2013:262-8.

29. Costantini S, Rusolo F, De Vito V, Moccia S, Picariello G, Capone F, et al. Potential anti-inflammatory effects of the hydrophilic fraction of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed oil on breast cancer cell lines. Molecules. 2014 Jun;19(6):8644-60.

30. Afaq F, Saleem M, Krueger CG, Reed JD, Mukhtar H. Anthocyanin‐and hydrolyzable tannin‐rich pomegranate fruit extract modulates MAPK and NF‐κB pathways and inhibits skin tumorigenesis in CD‐1 mice. International Journal of Cancer. 2005 Jan 20;113(3):423-33.

31. Adams LS, Seeram NP, Aggarwal BB, Takada Y, Sand D, Heber D, et al. Pomegranate juice, total pomegranate ellagitannins, and punicalagin suppress inflammatory cell signaling in colon cancer cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006 Feb 8;54(3):980-5.

32. Lansky EP, Newman RA. Punica granatum (pomegranate) and its potential for prevention and treatment of inflammation and cancer. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007 Jan 19;109(2):177-206.

33. de Nigris F, Williams-Ignarro S, Sica V, Lerman LO, D'Armiento FP, Byrns RE, et al. Effects of a pomegranate fruit extract rich in punicalagin on oxidation-sensitive genes and eNOS activity at sites of perturbed shear stress and atherogenesis. Cardiovascular Research. 2007 Jan 15;73(2):414-23.

34. Basu A, Schell J, Scofield RH. Dietary fruits and arthritis. Food & Function. 2018;9(1):70-7.

35. Ghavipour M, Sotoudeh G, Tavakoli E, Mowla K, Hasanzadeh J, Mazloom Z, et al. Pomegranate extract alleviates disease activity and some blood biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in Rheumatoid Arthritis patients. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017 Jan;71(1):92-6.

36. Balbir-Gurman A, Fuhrman B, Braun-Moscovici Y, Markovits D, Aviram M. Consumption of pomegranate decreases serum oxidative stress and reduces disease activity in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. The Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ. 2011 Aug;13(8):474.

37. Melnyk JP, Wang S, Marcone MF. Chemical and biological properties of the world's most expensive spice: Saffron. Food Research International. 2010 Oct 1;43(8):1981-9.

38. Hosseinzadeh H, Talebzadeh F. Anticonvulsant evaluation of safranal and crocin from Crocus sativus in mice. Fitoterapia. 2005 Dec 1;76(7-8):722-4.

39. Hosseinzadeh H, Shariaty VM. Anti-nociceptive effect of safranal, a constituent of Crocus sativus (saffron), in mice. Pharmacologyonline. 2007 Jan 1;2:498-503.

40. José Bagur M, Alonso Salinas GL, Jiménez-Monreal AM, Chaouqi S, Llorens S, Martínez-Tomé M, et al. Saffron: An old medicinal plant and a potential novel functional food. Molecules. 2018 Jan;23(1):30.

41. Tamaddonfard E, Farshid AA, Eghdami K, Samadi F, Erfanparast A. Comparison of the effects of crocin, safranal and diclofenac on local inflammation and inflammatory pain responses induced by carrageenan in rats. Pharmacological Reports. 2013 Sep;65(5):1272-80.

42. Hamidi Z, Aryaeian N, Abolghasemi J, Shirani F, Hadidi M, Fallah S, et al. The effect of saffron supplement on clinical outcomes and metabolic profiles in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research. 2020 Feb 11.

43. Rovenský J, Ferenčík M, Imrich R. Pathogenesis, Clinical Syndromology and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. InGerontorheumatology 2017 (pp. 1-22). Springer, Cham.

44. Hsieh PF, Hou CW, Yao PW, Wu SP, Peng YF, Shen ML, et al. Sesamin ameliorates oxidative stress and mortality in kainic acid-induced status epilepticus by inhibition of MAPK and COX-2 activation. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2011 Dec;8(1):1-0.

45. Helli B, Shahi MM, Mowla K, Jalali MT, Haghighian HK. A randomized, triple‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial, evaluating the sesamin supplement effects on proteolytic enzymes, inflammatory markers, and clinical indices in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Phytotherapy Research. 2019 Sep;33(9):2421-8.

46. Vadell AK, Bärebring L, Hulander E, Gjertsson I, Lindqvist HM, Winkvist A, et al. Anti-inflammatory Diet In Rheumatoid Arthritis (ADIRA)—a randomized, controlled crossover trial indicating effects on disease activity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2020 Jun 1;111(6):1203-13.

47. Khanna S, Jaiswal KS, Gupta B. Managing rheumatoid arthritis with dietary interventions. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2017 Nov 8;4:52.

48. Alwarith J, Kahleova H, Rembert E, Yonas W, Dort S, Calcagno M, et al. Nutrition interventions in rheumatoid arthritis: the potential use of plant-based diets. A review. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2019 Sep 10;6:141.

49. Forsyth C, Kouvari M, D’Cunha NM, Georgousopoulou EN, Panagiotakos DB, Mellor DD, et al. The effects of the Mediterranean diet on rheumatoid arthritis prevention and treatment: a systematic review of human prospective studies. Rheumatology International. 2018 May 1;38(5):737-47.

50. García-Morales JM, Lozada-Mellado M, Hinojosa-Azaola A, Llorente L, Ogata-Medel M, Pineda-Juárez JA, et al. Effect of a dynamic exercise program in combination with Mediterranean diet on quality of life in women with rheumatoid arthritis. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2020 Oct 1;26(7S):S116-22.

51. Nachvak SM, Alipour B, Mahdavi AM, Aghdashi MA, Abdollahzad H, Pasdar Y, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on matrix metalloproteinases and DAS-28 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clinical Rheumatology. 2019 Dec 1;38(12):3367-74.

52. Veselinovic M, Vasiljevic D, Vucic V, Arsic A, Petrovic S, Tomic-Lucic A, et al. Clinical benefits of n-3 PUFA and ɤ-linolenic acid in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrients. 2017 Apr;9(4):325.

53. Senftleber NK, Nielsen SM, Andersen JR, Bliddal H, Tarp S, Lauritzen L, et al. Marine oil supplements for arthritis pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Nutrients. 2017 Jan;9(1):42.

54. Petersson S, Philippou E, Rodomar C, Nikiphorou E. The Mediterranean diet, fish oil supplements and Rheumatoid arthritis outcomes: Evidence from clinical trials. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2018 Nov 1;17(11):1105-14.

55. Gioxari A, Kaliora AC, Marantidou F, Panagiotakos DP. Intake of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2018 Jan 1;45:114-24.

56. Abdulrazaq M, Innes JK, Calder PC. Effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on arthritic pain: A systematic review. Nutrition. 2017 Jul 1;39:57-66.

57. Javadi F, Ahmadzadeh A, Eghtesadi S, Aryaeian N, Zabihiyeganeh M, Rahimi Foroushani A, et al. The effect of quercetin on inflammatory factors and clinical symptoms in women with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2017 Jan 2;36(1):9-15.

58. Zamani B, Farshbaf S, Golkar HR, Bahmani F, Asemi Z. Synbiotic supplementation and the effects on clinical and metabolic responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Nutrition. 2017 Apr;117(8):1095-102.

59. Rudbane SM, Rahmdel S, Abdollahzadeh SM, Zare M, Bazrafshan A, Mazloomi SM, et al. The efficacy of probiotic supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology. 2018 Feb 1;26(1):67-76.