Abstract

Galantamine is an alkaloid extracted from plant bulbs of some members of the Amaryllidaceae family and is a reversible competitive inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase. GAL affects the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Since this effect indicates an immunomodulatory activity, we evaluated the efficacy of galantamine as an anti-inflammatory therapy in vivo in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) and collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). Mice were randomly divided into two groups: vehicle (treated with 0.9 % saline) and galantamine (GAL 4.4 mg/kg) with intraperitoneal administration. The AIA model was performed in Balb/C mice; nociception and leukocyte migration into the knee joint were evaluated after 24h of monoarthritis induction. The CIA was performed in DBA/1J mice with treatment starting after the disease onset with an 11 days duration. Evaluation of arthritis severity was made by clinical, histological scoring, body weight, edema, nociception, and collagen quantification. Our results showed that galantamine did not alter nociception and leucocyte articular migration in the AIA model and did not alter edema, nociception, clinical and histologic scoring in the CIA model. However, galantamine was able to maintain the collagen content in tibiotarsal joints of mice with CIA. In conclusion, galantamine may prevent collagen degradation in the joint by preserving both collagen content and the thickness of collagen fibers.

Keywords

Antigen-induced arthritis, Collagen-induced arthritis, Galantamine, Inflammation

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common autoimmune, systemic and inflammatory disease with unknown etiology characterized by progressive joint destruction and functional disability, affecting 0.5–1 % of the world population [1]. Current therapies available for RA are able to reduce disease symptoms with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) being considered the standard of care. Despite the advance in new therapeutic options in the last years, there is still a need to improve the management of the disease to reach a major range of patients [2]. In addition to the many side effects that can directly affect the patient’s quality of life, a significant ratio of patients are not responsive to available treatments and a few patients achieve full remission [3]. Therefore, additional options to improve RA therapy are needed.

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway has become a target to drug development for RA since it is capable to induce an anti-inflammatory response, which could suppress cytokine release through stimulation of the vagus nerve [4]. Vagus nerve activity has been implicated in the regulation of inflammation through a brain-integrated physiological mechanism called inflammatory reflex [5].

Galantamine (GAL), an alkaloid extracted from the bulb of Amaryllidaceae family plants, is a reversible competitive inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [6]. It is used as a centrally acting inhibitor approved for the symptomatic treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease [7,8]. GAL has a direct effect on the principal vagus nerve neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Ach) by modulating the α7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR), decreasing the release of proinflammatory cytokines [9-11], with forebrain acetylcholine as a major mediator of its effect [12].

In addition, it has been demonstrated that treatment with GAL improves rat adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) by reduction of paw swelling, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP), tumour necrosis factor alfa (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin (IL)-10, which indicates that this alkaloid has anti-inflammatory properties and a potential anti-arthritic effect [9]. However, since there is no universal model that reflects all articular and systemic features of the human disease a unique model of arthritis may not be reliable to evaluate the efficacy of a drug [13,14]. Thus, to provide more evidence about its effect, the present study intends to evaluate the efficacy of GAL as an anti-arthritic therapy in vivo in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) and collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice models.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Balb/C mice were used (male, 8-12 weeks 25-30 g) for the AIA model, and DBA/1J mice were used for the CIA model (male, 8-12 weeks, 18-22 g). Animals were kept in the Animal Experimental Unit of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA) during all the experimental period with controlled temperature conditions (22°C ± 2°C), 12 h light/dark cycles, 40-60% relative humidity and without restrictions of water and food intake. All procedures were performed in accordance and approved by the ethics committee for experimental use of animals from Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (permit number: 140155).

Treatment

Galantamine hydrobromide powder, without excipients, was provided and donated by Janssen (Beerse, Belgium) and was diluted in saline 0.9%. The GAL dosage used in both models was 4.4 mg/kg administered intraperitoneally (i.p). This dose was based on previous studies that demonstrated an anti-inflammatory activity of GAL [10,15]. A group of mice were treated with the vehicle of dilution (0.9% saline) as a positive control of CIA development and to assess the efficacy of GAL treatment.

Induction of AIA

Fifteen male Balb/C mice were induced through subcutaneous (sc) injection of an emulsion with 500 mg of methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in 0.1 mL of PBS and 0.1 mL of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) (1 mg/ml of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37Ra; Difco) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) administered on day 0. Booster injections were administered at 7 and 14 days after the first immunization with mBSA diluted in Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). In the 21º day, animals were challenged with mBSA (10 µg/cavity), dissolved in 10 μl of saline, into the left tibiofemoral joint, and injected at the contralateral joint with 10 μl of saline 0.9% alone as a negative control. Twenty-four hours before intraarticular (i.a) injection, animals were randomized into two groups: vehicle (0.9 % saline) and GAL (4.4 mg/kg) and received one dose of treatments with i.p administration. Nociception was performed at 0, 1, 3, 6 and 24 hours and mice were euthanized 24 h after i.a injection of mBSA to assess leukocyte migration to the joint [16].

Induction of CIA

Twenty-eight male DBA/1J mice were immunized at the base of the tail with 50 ml of an emulsion consisting of equal parts of CFA (2 mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and bovine collagen type II (CII) (2 mg/ml) (Chondrex, Redmond, WA, USA) in 10 mM acetic acid (day 0). After eighteen days, a booster injection was performed in another site of the tail with 50 ml of emulsion (CII and IFA). Immunized animals were randomized between two groups: vehicle (0.9 % saline) or GAL (4.4 mg/Kg) treatments were started at the onset of disease (after a first clinical sign of arthritis) and administered i.p daily within 11 days [17].

Clinical scoring of CIA

After booster injection, animals were monitored daily for clinical signs of arthritis to evaluate the development and severity of the disease, according to the followed score: 0 – normal; 1 – mild swelling and erythema; 2 – moderate swelling and erythema; 3 – severe swelling and erythema extending from the ankle to metatarsal joints; 4 – severe erythema and swelling with loss of function. The total score of each animal is the sum of the score in each paw (range: 0-16) [17].

Evaluation of articular nociception

Mice were placed in a quiet room in acrylic cages with a wire-grid floor for 15-30 minutes before testing for environmental adaptation. In these experiments, an electronic pressure meter, consisting of a hand-held force transducer fitted with a polypropylene tip (Insight Instruments, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) was used to apply a force in the sub-plantar surface resulting in a tibiotarsal joint flexion. The results expressed as the flexion-elicited withdrawal threshold in grams. In the AIA model, nociception of the knee joint was evaluated on 0, 1, 3, 6 and 24 h after i.a injection of mBSA, and the CIA model was evaluated on days 0, 2, 5, 8 and 11 after the onset of disease [18].

Evaluation of edema in CIA

Paw volume was measured with plethysmometer (Insight Instruments, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) in all animals before CIA induction (day 0) and this analysis was repeated 2, 5, 8 and 11 days after onset of disease, as previously described [19]. The amount of paw swelling was determined for each mouse and expressed in mm³.

Evaluation of leukocytes migration in AIA

It was evaluated the leukocytes migration into the knee joints of mice at the end of the experimental period. Mice were euthanized, and joint cavities were washed three times with 5 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing EDTA 1 mM and then diluted to a final volume of 100 μl of PBS/EDTA. The total number of leukocytes was determined by the Neubauer chamber diluted in Turk's solution (1:1) under optical microscopy (100x magnification) with a manual counter and expressed as the number of cells x 104/joint cavity [16].

Histologic scoring of arthritis and evaluation of cartilage destruction in CIA

DBA/1J mice were euthanized 11 days after arthritis development, and the ankles were dissected and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 72 h and then decalcified with 10% nitric acid for 48 h. Tissues were sectioned and embedded in paraffin. For the histologic scoring of arthritis, slides were stained with HE, and a previously described histologic scoring system was used [18]. Briefly, it was used a scoring system for joints with the following parameters: synovial inflammation, synovial hyperplasia, pannus formation, cartilage erosion, and bone erosion. Staining slides were interpreted by two blinded and independent investigators.

To assess the severity of cartilage destruction, slides were stained with O-safranin and we used a previously described score: 0 – normal, 1 – minimal (loss of O-safranin staining only), 2 – mild (loss of staining and mild cartilage thinning), 3 – moderate (moderate cartilage destruction reaching the middle zone), 4 – marked (marked cartilage destruction reaching the deep zone) and 5 – severe (severe cartilage destruction reaching the tidemark) [20].

Quantification of collagen in CIA

Stained joints with picrosirius red and a polarized light assessment followed by image software analysis to quantify collagen content. Briefly, images of the sections were acquired using a microscope equipped with two aligned filters to provide a polarized illumination (Olympus Life Science, Waltham, MA, USA). It was used ImageJ for the analyzes (version 1.52a) (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to determine the total number of pixels in the image as well as the colour of each pixel, using the following hue definitions: red 2-9 and 230-255, orange 10-38, yellow 39-51, green 52-128. The total number of collagen pixels (red, orange, yellow and green) was determined and expressed as a ratio with the total number of pixels in the image, and the number of pixels within each hue range was expressed as a percentage of the total number of collagen pixels [21].

Statistical analysis

Data are present as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used for leukocytes migration and two-way ANOVA was used for nociception and clinical score with Bonferroni’s adjustment for multiple comparisons. Mann-Whitney t-test for histological and O-safranin scoring and an unpaired t-test for collagen quantification. Statistical differences were considered significant with a p-value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Treatment with GAL did not alter inflammatory parameters in the AIA model

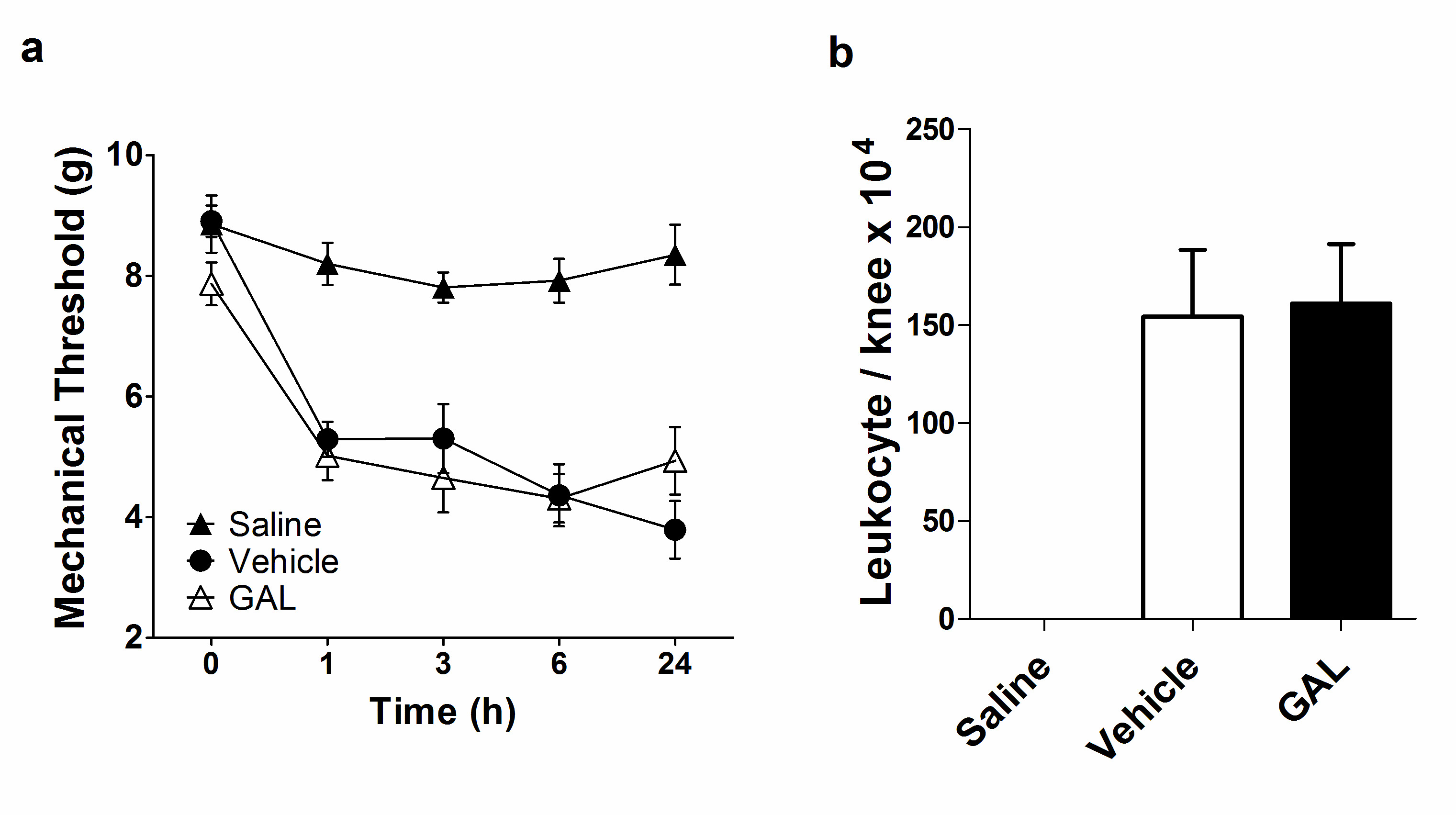

After the mBSA joint injection, the nociception of the knee joint was evaluated on 0, 1, 3, 6 and 24 h in AIA. Vehicle-treated mice had a significant increase in nociception since 1 hour after i.a injection and a larger increase at 24 h (3.793 ± 1.263 g) compared with the control group. This behavior indicates the efficacy of the inflammatory process induced by the mBSA challenge applied in this model. Likewise, The GAL-treated mice presented a similar nociception profile to the vehicle group (4.938 ± 1.584 g), however with a peak at 6 hour, followed by improvement at 24h, although without statistical significance (Figure 1a). Leukocytes migration induced by mBSA i.a injection was assessed in the knee joint after 24 h of monoarthritis induction, and both vehicle (154.4 ± 89.79 leukocytes/knee x 104) and GAL (161 ± 85.67 leukocytes/knee x 104) groups presented massive leukocytes migration (Figure 1b). The Saline group maintained stable nociception values and presented no leukocytes migration, indicating that there was no inflammatory process induced by i.a injection.

Figure 1. Effect of galantamine (4.4 mg/kg) in articular nociception and leukocytes migration in antigen-induced arthritis (AIA). (a) Treatment with galantamine in AIA model did not ameliorate nociception compared with the vehicle (p=0.877 at 24 h). (b) Treatment with galantamine did not decrease leukocyte migration into the knee joint compared to the vehicle group (p=0.887). Data are presented as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test were used for leukocytes migration and nociception, respectively.

Treatment with GAL reduced collagen degradation in ankle joints of CIA mice

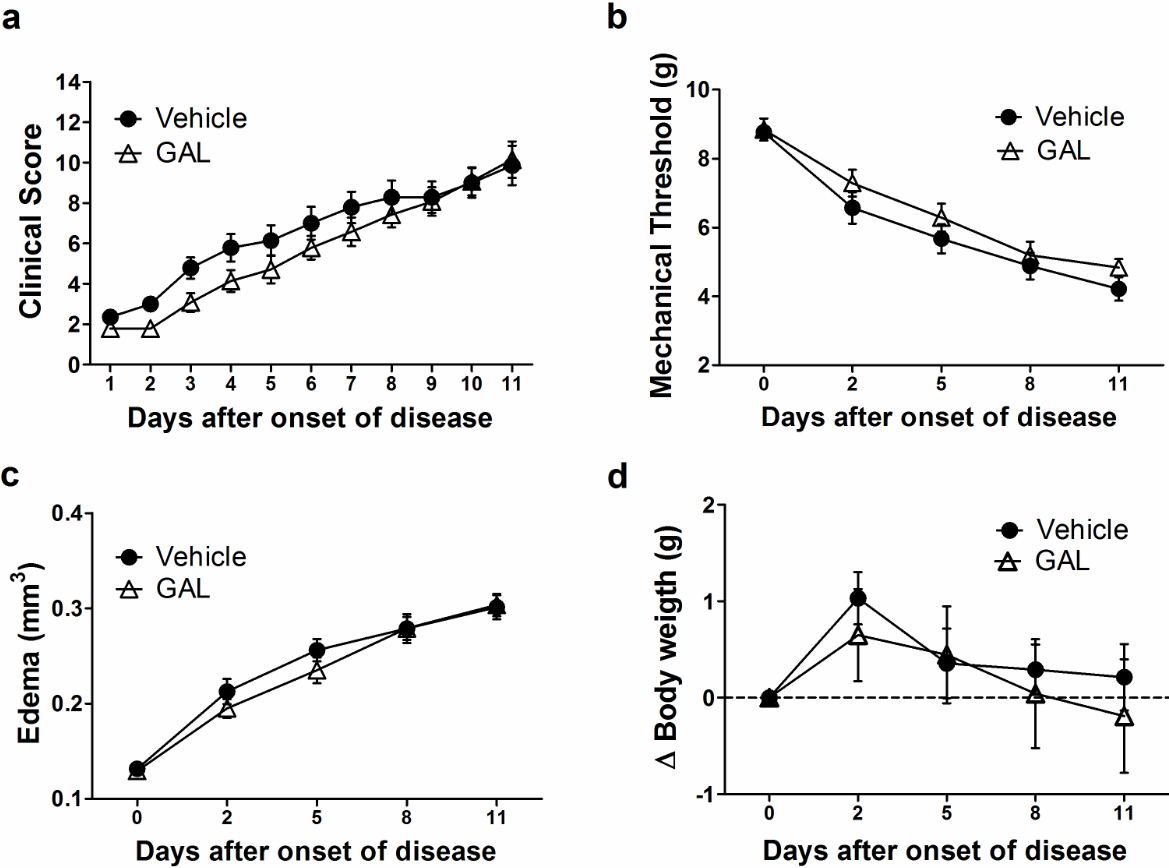

Both groups treated with 0.9% saline or GAL presented a similar onset time of arthritis (vehicle: 24.71 ± 6.04; GAL: 26.17 ± 4.62 days after CIA induction) and incidence, with all animals affected at day 32 after the induction of disease (Supplementary Information, figure S1). Nevertheless, treatment started after the onset of disease and the severity score of arthritis presented a similar development between the vehicle (9.86 ± 3.65) and GAL-treated groups (10.14 ± 3.37) at the end of the experiment period (Figure 2a). There was an increase in inflammation-related nociception in both groups for two days after the first clinical sign of arthritis. The highest nociception value occurred on day 11 after the onset of disease (4.33 ± 1.12 g), and treatment with GAL did not present any anti-nociceptive effect (4.84 ± 0.94 g) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Effect of galantamine (4.4 mg/kg) in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). (a) Galantamine was not able to reduce the clinical score of disease (p=0.217). (b) Nociception was not ameliorated by galantamine treatment (p>0.05). (c) Edema measured in hind paw did not show improvement with galantamine (p>0.05). (d) Bodyweight measures did not present any difference between groups (p>0.05). Data are presented as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM).

As a result of severe arthritis development, it was observed increased paw edema in the vehicle and the GAL-treated mice in this set of experiments. Since two days after the disease onset, paw swelling had increased in both groups with the highest value on day 11 (vehicle: 0.301 ± 0.046 mm3; GAL: 0.303 ± 0.044 mm3) (Figure 2c). Additionally, there was no statistical difference between both experimental groups. Regarding body weight, the vehicle presented a stabilized body weight (0.21 ± 1.28g), and GAL-treated mice presented a loss of weight at the end of the experimental procedure (-0.19 ± 2.2g) (Figure 2d).

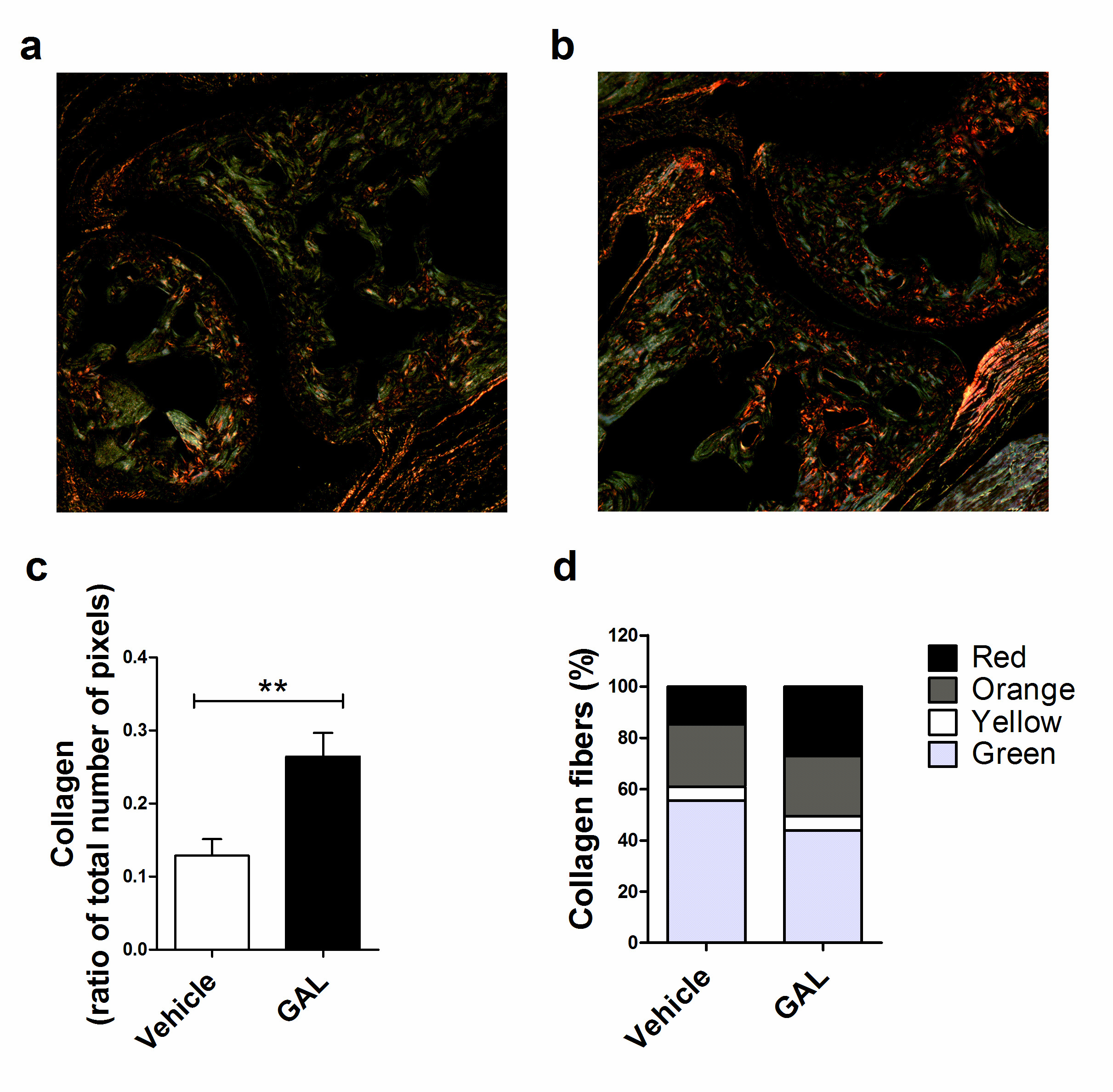

CIA development is marked by the release of metalloproteinases (MMPs), which results in the degradation of extracellular matrix components, like collagen [14]. Collagen can be observed by staining the tissue section with picrosirius red and, in addition, collagen fiber thickness can be assessed when observed with polarized light, since as fiber thickness increases, the color changes from green to yellow to orange and, finally, to red [21]. In this way, GAL-treated mice presented a higher amount of collagen (0.264 ± 0.073 pixels) in the ankle joint compared to vehicle-treated mice (0.128 ± 0.060 pixels) (p<0.01) (Figure 3a, 3b, 3c), decreasing the percentage of green collagen fibers (GAL: 43.8%; Vehicle: 55.5%) and increasing of red collagen fibers proportion (GAL: 27.2%; Vehicle: 14.8%) (Figure 3d).

Figure 3. Picrosirius Red staining of ankle joints from mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). (a) Vehicle-treated mice with CIA showed collagen degradation, with primarily thin fibers (green). (b) Galantamine-treated mice showed less collagen degradation, presenting thicker fibers (red). (c) Treatment with galantamine reversed collagen degradation of CIA (p<0.05; unpaired T-test). (d) The proportion of collagen fibers in vehicle and galantamine treated mice. Values represent mean and standard error of the mean (SEM).

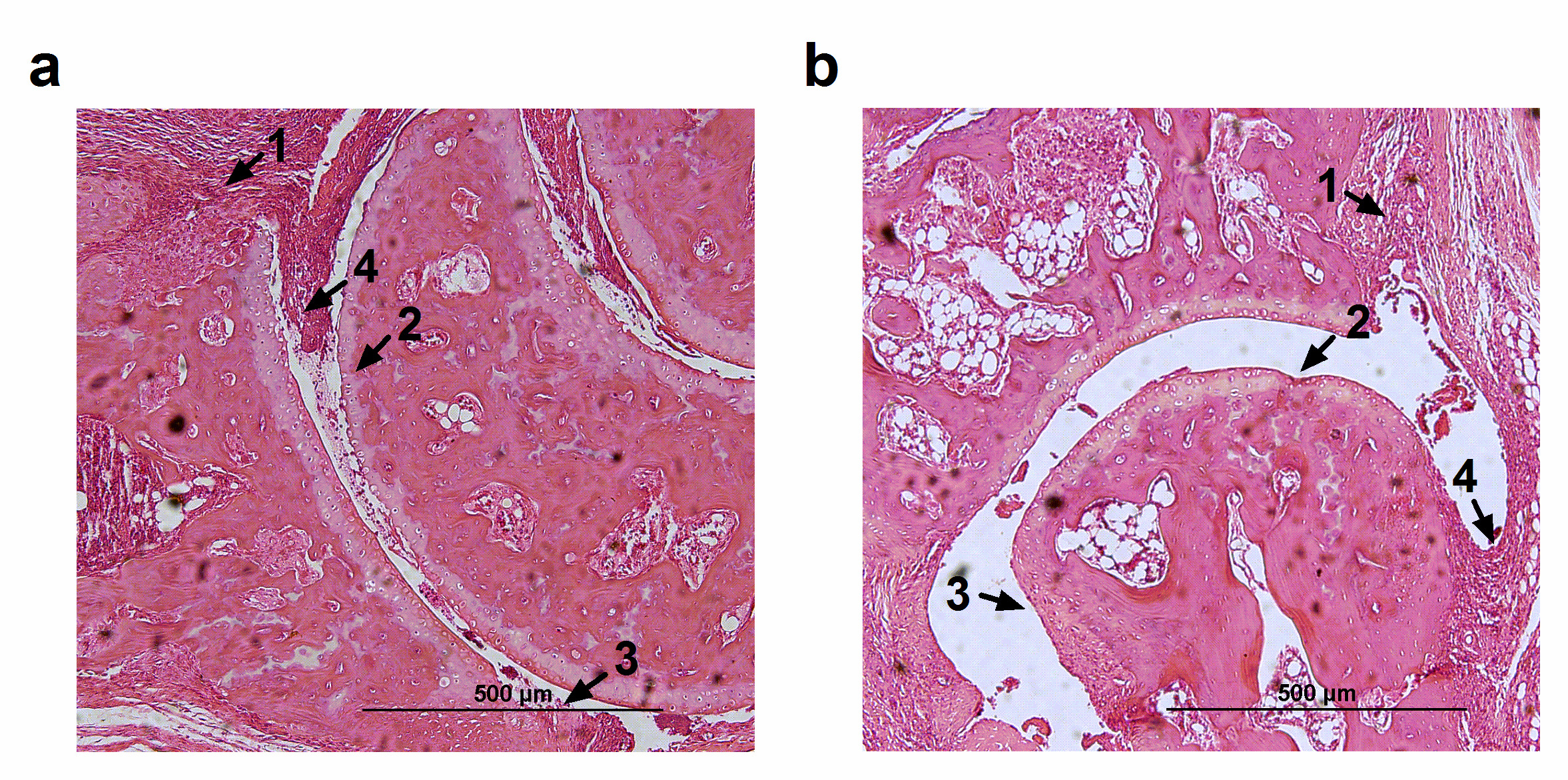

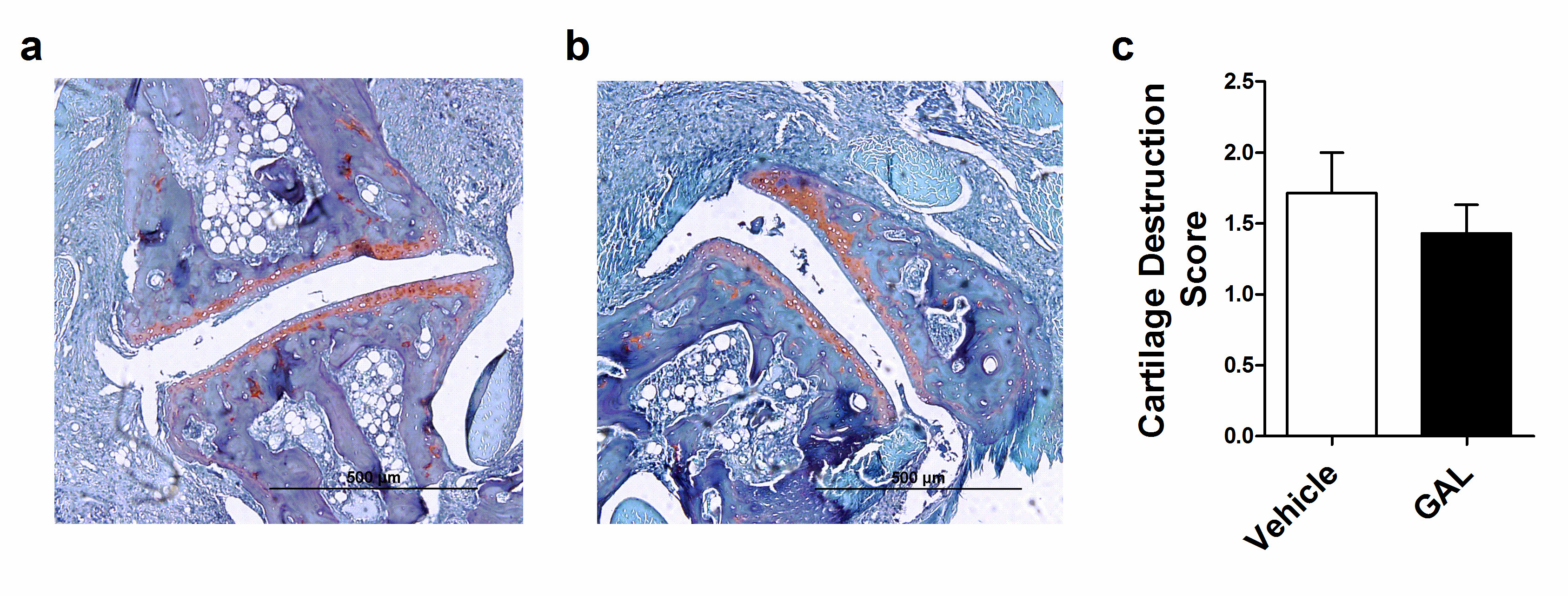

In HE analyses, vehicle-treated mice presented synovial inflammation, characterized by a great influx of inflammatory cells; an extended pannus formation and histological damage, characterized by large cartilage and bone erosion, without presenting synovial hyperplasia (Figure 4a). Beyond that, GAL-treated mice presented a similar histologic profile (Figure 4b), but bone erosion presented a no significant decrease in GAL-treated mice (Table 1). Additionally, the vehicle-treated mice presented mild cartilage destruction (Figure 5a), a feature that was not ameliorated by GAL treatment (Figure 5b, 5c).

Figure 4. Histopathology of ankle joints from mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). (a) Vehicle-treated mice with CIA showed infiltration of inflammatory cells with pannus formation and large cartilage and bone erosion. (b) Treatment with galantamine did not improve histopathologic parameters of CIA. 1-Infiltration of inflammatory cells, 2- Cartilage erosion, 3- Bone erosion, 4- Pannus.

Figure 5. O-safranin staining of ankle joints from mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA). (a) Vehicle-treated mice with CIA showed mild cartilage destruction. (b) Treatment with galantamine did not improve cartilage destruction of the CIA. (c) Values represent median and percentiles (25-75) by the Mann-Whitney t-test (p=0.520).

|

|

Vehicle |

GAL 4.4 mg/Kg |

|

Synovial inflammation (0-3) |

1.75 (1.4-3) |

1.75 (1-2.1) |

|

Extension of pannus (0-3) |

1.5 (1.0-2.2) |

1.25 (0.9-1.5) |

|

Cartilage erosion (0-3) |

1.25 (0.5-2.0) |

1 (0.5-1.5) |

|

Bone erosion (0-3) |

1 (0.5-1.6) |

0.5 (0.4- 1.5) |

|

Treatment with galantamine 4.4 mg/Kg did not improve histopathologic parameters of collagen-induced arthritis. Values represent median and percentiles (25-75) by Mann-Whitney t-test and histologic scores are on a scale of 0-3 for all measures. |

||

Discussion

Currently, therapies available for RA can reduce the disease symptoms; however, most patients are not able to achieve remission since there is no drug available that can cover all aspects of this disease [22,23]. Once GAL presented an anti-inflammatory property and a potential antirheumatic effect in AA model, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate the effect of GAL in two different animal models of arthritis, which exhibit several aspects of the human disease [24]. Besides GAL did not show protective effects in both experimental models, it was able to maintain collagen content in the ankle joints of mice.

A common feature in RA is joint damage due to cartilage and bone degradation. An important mechanism involved in the joint damage process is the production of proteases such as MMPs by synovial macrophages, neutrophils and synovial fibroblasts, which led to degradation of, among other extra-cellular matrix structures, collagen, one of the major components in joint [25]. Additionally, α7nAChR seems to be related with collagen homeostasis, since its deficiency exacerbates hepatic fibrosis in mice with non?alcoholic steatohepatitis [26] and kidney fibrosis in mice with glomerulonephritis [27], indicating a role of this receptor in decreasing collagenases MMPs. In this sense, we found that mice treated with GAL presented more collagen and thicker fibers in the joint than vehicle-treated mice. The impact of GAL on collagen content corroborates the effect of its mechanism of action in decreasing collagenases but indicates it has no effective effect over gelatinases, highlighting the importance of these MMPs in RA joint destruction.

Different studies using GAL as a treatment in inflammatory models such as obesity, LPS and colitis have shown that it is capable of reducing inflammation. In a mice obesity model, GAL induced reduction of body weight and inflammation and decreased IL-6 and MCP-1 plasma levels [10]. In the LPS-induced acute lung injury model, GAL pre-treatment attenuated pathological changes in lung tissue and inhibited the high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) expression. Furthermore, the treatment decreased leukocytes infiltration and secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α in rat lung tissue [6]. In the mice colitis model, the daily administration of GAL alleviated inflammation severity of colitis since the treatment led to a reduction of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α colonic level (Ji et al. 2014).

According to Wong et al. galantamine administration (4 mg/kg, I.P) was able to decreased body weight as well as food intake in obese and lean mice in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) particually because GAL activates the vagal-mediated cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway [29]. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors like galantamine have the most common adverse symptoms as gastrointestinal effects, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [30,31]. Although there is some conflicting data about weight loss in the use of GAL (with or without gastrointestinal symptoms) is a significant risk of AChEI such as galantamine use and has been reported to occur in up to 20% of patients with dementia [31,32]. In addition, Gowayed et al. [9] verified an anti-arthritic effect of GAL in rats with AA. The highest dose tested with GAL (5 mg/kg) reversed body weight loss; ameliorated paw swelling and inflammation through reducing anti-CCP, TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-10 levels. Moreover, a recent study used the AA model in rats investigated the efficiency of GAL through a novel transdermal patch compared to oral GAL demonstrated that oral and transdermal treatment with GAL was able to reduce inflammatory biomarkers such as TNF-α, IL-1β, JAK2, CRP and enhance IL-10 [33]. In this present study, we provide data in acute and chronic mice models of RA, body weight do not presented differences between groups and the treatment with GAL was not able to prevent the clinical manifestations and ameliorate the disease severity in both models, but was able to prevent the collagen content in the joint.

The AIA model is one of the most monoarthritis models used and it is performed by mBSA as an antigen [34]. This model may generate an acute joint inflammation characterized by swelling, polymorphonuclear cells infiltration and pronounced hyperalgesia mediated by the adaptive immune system in a period of 24 h [35]. On the other hand, the development of CIA [36] is dependent on both innate and adaptive immune response that leads to chronic polyarthritis with joint inflammation and cartilage and bone erosion [37].

Most of the approved drugs for RA have data on therapeutic efficacy in AIA and CIA. Combining the two models, we created an experimental design more similar to human disease. Thus, these animal models are more predictive of clinical efficacy than data from either model alone [14,38]. However, in the AA model, which also was used to test the anti-arthritic effect of GAL [9], the cartilage destruction is mild in comparison to the inflammation and cartilage destruction that occurs in AIA and CIA models. Therefore, the AA model alone may not be reliable for potential treatment effects evaluation [39].

An important issue in new pharmacological approaches is how the drug in the study is managed. The administration route, dosage, and vehicle of dilution can be an important bias in experimental pharmacodynamics. In this sense, our study presents as limitations the lack of analyzing more than one dose and route of administration of GAL. However, similarities in the treatment methodology applied in other GAL studies on inflammatory animal models as a route of administration and dosage indicate that the administration of GAL in the present study was not a factor that interfered with drug absorption and effect. Doses applied in colitis, obesity, LPS-induced acute lung injury and AA models were compatible with the doses used in both AIA and CIA models. Furthermore, other parameters such as administration route and treatment frequency corroborate with the methods applied in the present study [9,10,28]. Thus, doses, route of administration and treatment frequency do not seem to be interfering in a possible therapeutic effect of GAL in our study.

In conclusion, the administration of GAL was unable to improve the disease in both acute and experimental models of arthritis but preserved the collagen content in the joint which can have a positive impact on RA joint degradation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the employees from Unidade de Experimentação Animal and Unidade de Patologia Experimental from Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for providing scholarships to Bárbara Jonson Bartikoski and Renata Ternus Pedó; the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for providing scholarships to Mirian Farinon and Eduarda Correa Freitas.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Disclosure of statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by Fundação de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE-HCPA) [Grant number 140155].

Authors’ Contributions

Bárbara Jonson Bartikoski and Renata Ternus Pedó contributed equally to this study.

Ethical Approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

2. Jin Y, Desai RJ, Liu J, Choi NK, Kim SC. Factors associated with initial or subsequent choice of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2017 Jul 5;19(1):159.

3. Abbott JD, Moreland LW. Rheumatoid arthritis: developing pharmacological therapies. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2004 Aug 1;13(8):1007-18.

4. Oke SL, Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex and the role of complementary and alternative medical therapies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009 Aug;1172:172-80.

5. Consolim-Colombo FM, Sangaleti CT, Costa FO, Morais TL, Lopes HF, Motta JM, et al. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome in a randomized trial. JCI Insight. 2017 Jul 20;2(14).

6. Li G, Zhou CL, Zhou QS, Zou HD. Galantamine protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016 Feb;49(2):e5008.

7. Ohta Y, Darwish M, Hishikawa N, Yamashita T, Sato K, Takemoto M, et al. Therapeutic effects of drug switching between acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2017 Nov;17(11):1843-8.

8. Woodruff‐Pak DS, Lander C, Geerts H. Nicotinic cholinergic modulation: galantamine as a prototype. CNS Drug Reviews. 2002 Dec;8(4):405-26.

9. Gowayed MA, Refaat R, Ahmed WM, El-Abhar HS. Effect of galantamine on adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015 Oct 5;764:547-53.

10. Satapathy SK, Ochani M, Dancho M, Hudson LK, Rosas-Ballina M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, et al. Galantamine alleviates inflammation and other obesity-associated complications in high-fat diet-fed mice. Molecular Medicine. 2011 Jul;17(7):599-606.

11. Wazea SA, Wadie W, Bahgat AK, El-Abhar HS. Galantamine anti-colitic effect: Role of alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in modulating Jak/STAT3, NF-κB/HMGB1/RAGE and p-AKT/Bcl-2 pathways. Scientific Reports. 2018 Mar 23;8(1):5110.

12. Lehner KR, Silverman HA, Addorisio ME, Roy A, Al-Onaizi MA, Levine Y, et al. Forebrain cholinergic signaling regulates innate immune responses and inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019 Apr 2;10:585.

13. Hegen M, Keith JC, Collins M, Nickerson-Nutter CL. Utility of animal models for identification of potential therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008 Nov 1;67(11):1505-15.

14. Kollias G, Papadaki P, Apparailly F, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Holmdahl R, Baumans V, et al. Animal models for arthritis: innovative tools for prevention and treatment. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2011 Aug 1;70(8):1357-62.

15. Pavlov VA, Parrish WR, Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Puerta M, Ochani K, et al. Brain acetylcholinesterase activity controls systemic cytokine levels through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009 Jan 1;23(1):41-5.

16. Farinon M, Clarimundo VS, Pedrazza GP, Gulko PS, Zuanazzi JA, Xavier RM, et al. Disease modifying anti-rheumatic activity of the alkaloid montanine on experimental arthritis and fibroblast-like synoviocytes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2017 Mar 15;799:180-7.

17. Brand DD, Latham KA, Rosloniec EF. Collagen-induced arthritis. Nature Protocols. 2007 May;2(5):1269-75.

18. Oliveira PG, Grespan R, Pinto LG, Meurer L, Brenol JC, Roesler R, et al. Protective effect of RC‐3095, an antagonist of the gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor, in experimental arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011 Oct;63(10):2956-65.

19. Grespan R, Fukada SY, Lemos HP, Vieira SM, Napimoga MH, Teixeira MM, et al. CXCR2‐specific chemokines mediate leukotriene B4–dependent recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed joints in mice with antigen‐induced arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2008 Jul;58(7):2030-40.

20. Feng ZY, He ZN, Zhang B, Li YQ, Guo J, Xu YL, et al. Adenovirus-mediated osteoprotegerin ameliorates cartilage destruction by inhibiting proteoglycan loss and chondrocyte apoptosis in rats with collagen-induced arthritis. Cell and Tissue Research. 2015 Oct;362(1):187-99.

21. Rich L, Whittaker P. Collagen and Picrosirius Red Staining: A Polarized Light Assessment of Fibrillar Hue and Spatial Distribution. Brazilian Journal of Morphological Sciences. 2005;22(2):97-104.

22. Nam JL, Takase-Minegishi K, Ramiro S, Chatzidionysiou K, Smolen JS, Van Der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017 Jun 1;76(6):1113-36.

23. Winthrop KL, Weinblatt ME, Crow MK, Burmester GR, Mease PJ, So AK, et al. Unmet need in rheumatology: reports from the targeted therapies meeting 2018. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2019 Jul 1;78(7):872-8.

24. Asquith DL, Miller AM, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. European Journal of Immunology. 2009 Aug;39(8):2040-4.

25. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Feb 8;4:18001.

26. Kimura K, Inaba Y, Watanabe H, Matsukawa T, Matsumoto M, Inoue H. Nicotinic alpha‐7 acetylcholine receptor deficiency exacerbates hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a mouse model of non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2019 May;10(3):659-66.

27. Truong LD, Trostel J, Garcia GE. Absence of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit amplifies inflammation and accelerates onset of fibrosis: An Inflammatory Kidney Model. The FASEB Journal. 2015 Aug;29(8):3558-70.

28. Ji H, Rabbi MF, Labis B, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ, Ghia JE. Central cholinergic activation of a vagus nerve-to-spleen circuit alleviates experimental colitis. Mucosal Immunology. 2014 Mar;7(2):335-47.

29. Pruekprasert N, Meng Q, Xie H, Cooney RN. Galantamine Causes Weight Loss and Improves Glycemic Control in Diabetic Mice. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2020 Oct 1;231(4):S22.

30. Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: evidence-based recommendations. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. Mar-Apr 2003;11(2):131-45.

31. Hughes A, Musher J, Thomas S, Beusterien K, Strunk B, Arcona S. Gastrointestinal adverse events in a general population sample of nursing home residents taking cholinesterase inhibitors. The Consultant Pharmacist®. 2004 Aug 1;19(8):713-20.

32. Stewart JT, Gorelik AR. Involuntary weight loss associated with cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006 Jun;54(6):1013-4.

33. Kandil LS, Hanafy AS, Abdelhady SA. Galantamine transdermal patch shows higher tolerability over oral galantamine in rheumatoid arthritis rat model. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 2020 Jun 2;46(6):996-1004.

34. Brackertz D, Mitchell GF, Mackay IR. Antigen‐induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1977 Apr;20(3):841-50.

35. Ferraccioli G, Bracci-Laudiero L, Alivernini S, Gremese E, Tolusso B, De Benedetti F. Interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 in arthritis animal models: roles in the early phase of transition from acute to chronic inflammation and relevance for human rheumatoid arthritis. Molecular Medicine. 2010 Nov;16(11):552-7.

36. Trentham DE, Townes AS, Kang AH. Autoimmunity to type II collagen an experimental model of arthritis. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1977 Sep 1;146(3):857-68.

37. Ebbinghaus M, Gajda M, Boettger MK, Schaible HG, Bräuer R. The anti-inflammatory effects of sympathectomy in murine antigen-induced arthritis are associated with a reduction of Th1 and Th17 responses. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2012 Feb 1;71(2):253-61.

38. Caplazi P, Baca M, Barck K, Carano RA, DeVoss J, Lee WP, et al. Mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Veterinary Pathology. 2015 Sep;52(5):819-26.

39. Joe B, Wilder RL. Animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Molecular Medicine Today. 1999 Aug 1;5(8):367-9