Abstract

Background: Microbes can influence development and trigger asthma attacks. Therefore, this study evaluated the more dominant microbial infections that trigger attacks in children.

Methods: Forty-one nasopharyngeal and oro-pharyengeal swabs were obtained from the Pediatric Allergy Clinic of two educational hospitals and sent to a Molecular Laboratory to evaluate 21 bacterial and viral respiratory pathogens using the qPCR-TaqMan method.

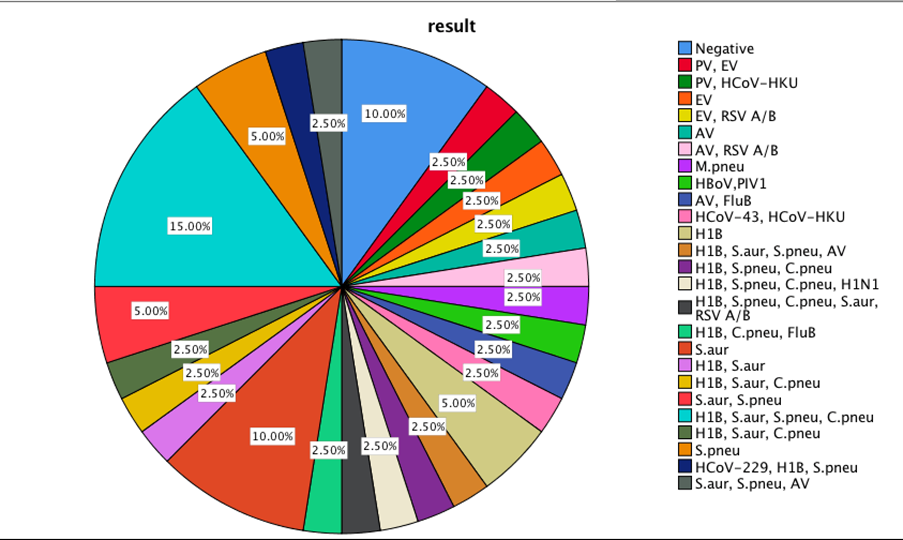

Results: The main bacterial infections were S. aureus (S. aur) 18/41 (43.9%), S. pneumoniae (S. pneu) 16/41 (39%), C. pneumoniae (C. pneu) 12 /41 (29.3%), and Haemophilus influenza Type B (HIB) 17/41 (41.5%) while the most viral infections were Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (HRSV) 3/41 (7.3%) and Influenza type B (Flu.B), HRV, Human Metapneumoviruses (HMPVA.B), Human Para-Influenza Viruses (HPIV)-2,3,4, Human Coronaviruses (HcoV)-63, and HcoV-229 in 2 cases (4,9%), in asthmatic children. Although bacterial infections were more common in both genders, the agents' frequency was statistically different between girls and boys (P=0.02). There was a positive correlation between S. pneu infection, asthma attack, and bronchitis (P= 0.02 and P= 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, a positive correlation was found between AV and RSVA.B infections with allergic rhinitis (P= 0.02 and P= 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion: In conclusion, bacterial respiratory infections, particularly, HIB, S. aur and S. pneu, were more common; however, HRSV and Flu. B has been a dominant viral infection in asthmatic attacks.

Keywords

Asthma, Bacterial, Viral infections, Allergy

Abbreviations

HRSV: Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus; FluA: Influenza type A; FluB: Influenza type B; HPIV: Human Para-Influenza Viruses; HCoV: Human Coronaviruses; HMPV: Human Metapneumoviruses; HRV: Human Rhinovirus; PV: Human Parechoviruses; M. pneu: Mycoplasma pneumoniae; C. pneu: Chlamydia pneumoniae; HIB: Haemophilus influenza Type B; S. aur: Staphylococcus aureus; S. pneu: Streptococcus pneumoniae

Background

Asthma is classified as an inflammatory airway disorder. The triggering factors, such as aeroallergens, air pollutants, and viral infections, promote asthma symptoms [1-3]. Despite the progress made in the prevention and management of the disease, unfortunately, the number of morbidities is increasing every year [4-6].

Asthma is the most common persistent disease in childhood. The prevalence of asthma has been increased by 12.6% from 1990 to 2020 [7,8]. Currently, asthma has stricken more than 300 million individuals worldwide. Even though physicians can improve their life span by using new therapeutic regimes, around 250,000 patients still expire annually [5,8]. Moreover, allergic anaphylaxis and asthma attacks are the major life-threatening events in asthmatic patients. Despite durable attempts of researchers to discover the exact pathogenesis of asthma attacks, the precise mechanism is not fully understood.

In general, microbial agents in pulmonary diseases are the main inducing and progressive factors in their clinical exacerbation; asthma is no exception. More than eighty percent of asthma exacerbation conditions accrued in children are mainly caused by respiratory viruses dependent on the region of living [9-11].

In asthma, any colonized respiratory microbial infection in the airways can induce inflammatory reactions in which the mediators and chemokines recruit neutrophils and eosinophils, consequently triggering asthmatic reactions [12,13].

In vitro studies suggested that the airway epithelium of subjects with asthma is defective in the production of the first line of viral defence [14]. In school children, the main pathogen identified in symptomatic asthma subjects is Human rhinovirus (HRV) [15]. However, many other respiratory viruses including Adenovirus (AdV), Bocavirus (BoV), Coronavirus (CoV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Enterovirus (EnV), Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Influenza virus (IFV), Metapneumovirus (MPV), Parainfluenza virus (PIV), and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) have been identified for triggering the asthma exacerbation [16,17].

For example, a study on 175 children aged 2–15 years showed that HRV (73%), followed by IFV A (27%) and RSV (7.7%), were the most frequent viruses associated with asthma exacerbations. Despite the frequency of viral infections in asthma promotion, many other infections by bacteria and fungi, including M. pneumoniae (M.p), S. pneumonia (S.p), C. pneumoniae (C.p), H. influenza (H.in) and Aspergillus spp can induce the asthma crisis [18,19]. However, bacterial infections may sometimes occur due to the post-viral infection and exacerbate the asthma reactions [19]. The type of infections and their association with asthma depend on the living area, seasonal conditions, population density and behavioral habits [20]. Therefore, prompt and accurate diagnosis is the initial attempt in infection monitoring and surveillance because it leads to appropriate treatment choices and prevention of overusing antibiotics. This study was conducted for the discovery of microbial agents in a pilgrimage, touristic region (Khorasan Razavi Province) with 6.2 million residents and around 25 million mobile population annually (Census 2011, https://www.amar.org.ir/Portals/1/Iran/census-2.pdf). This region could be a model for such an area to be monitored to prevent the spreading. The current study evaluated the frequency and implication of respiratory viruses and bacteria in pediatric asthma exacerbations for 21 of the most reported microbial agents in the literature.

Methods

Sample preparation

A total of 41 nasopharyngeal and oro-pharyengeal swabs were obtained from the Pediatric Allergy Clinic of the educational hospitals, the affiliates of the Medical School, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS) and in a transfer medium were sent to Navid Molecular Medical Laboratory for evaluation during January 2016 to December 2016. The inclusion criteria were the pediatric asthma subjects 4-16 years of age with productive cough and children who had not received antibiotics during the previous month. The inclusion criteria included lack of other autoimmunity or other immunopathologic disorders, asthmatic children without any severe asthma attack, who attended for periodic clinical assessment, without any underlying disease such as cardiac disorder or bronchiectasis and duration of recent illness five days or longer. The demographic and clinical assessments were collected from their clinical records. The exclusion criteria consisted of patients with any underlying disease such as cardiac disorder, bronchiectasis, duration of recent illness for five days or longer before visiting the clinic and antibiotic consumption. The Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research approved the study with the approval code of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS: 931307). Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from the participants and their parents.

DNA/RNA extraction

According to the manufacturer's instructions, DNA/RNA was extracted using a pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany). The extracted DNA was recovered in 50 μL of the elution buffer and stored at -20°C.

Quantitative multiplex real-time PCR

The FTD Respiratory Pathogens 21-plus kit (Fast Track Diagnostics, Luxembourg) six was used for the detection of the following pathogens causing respiratory infections: Influenza A, Influenza A (H1N1) swl, Influenza B, Coronaviruses NL63, 229E, OC43 and HKU1, Parainfluenza1, 2, 3 and 4, human MetapneumovirusA and B, Rhinovirus, Respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, Adenovirus, Enterovirus, Parechovirus, Bocavirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae B, and Staphylococcus aureus. All the real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed using a Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument (Qiagene, Germany). The real-time PCRs were performed as follows: 50°C for 15 min, 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 8 s, 60°C for 34 s. Simplifying the two-step method increased the analysis's repeatability and the reaction's efficiency. Negative control (sterile water) and positive control (DNA from the bacterial strain) were included in each run.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square tests were used to analyze the categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package, version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). The P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographic

The participants' mean age (mean ± SEM) was 6.6 ± 0.46 years (range of 2-16 years). Twenty-nine cases were males and 12 females.

Microbial infections

The central microbial infections among these asthmatic children were H1B and HRSV, with frequency of 41.5% (17/41) and 7.3% (3/41), respectively. In the case of the infection by influenza viruses, only flu-B infection was observed in 2 cases (4,9%), while Flu-A, HRV, HMPVA. B, HPIV-2,3,4, HcoV-63, and HcoV-229 were not observed in these asthmatic children. The actual incidence of 21 microbial infections among children with asthma symptoms is presented in Table 1.

|

Respiratory Pathogens |

Positive outcomes, n (%) |

|

S.aurs |

18 (43.9) |

|

H1B |

17 (41.5) |

|

S.pneu |

16 (39) |

|

C.pneu |

12 (29.3) |

|

HRSV-A,B |

3 (7.3) |

|

PV |

2 (4.9) |

|

EV |

2 (4.9) |

|

HCoV-43 |

2 (4.9) |

|

HCoV-HKU |

2 (4.9) |

|

FluB |

2 (4.9) |

|

H1N1 |

1 (2.4) |

|

HPIV-1 |

1 (2.4) |

|

HBoV |

1 (2.4) |

|

M.pneu |

1 (2.4) |

|

Rhino |

0 |

|

HMPVA.B |

0 |

|

HPIV 2,3,4 |

0 |

|

HCoV 63,229 |

0 |

According to non-parametric Chi-square and Pearson correlation analysis, a positive correlation was found between H1N1 infection with asthma, bronchitis and food allergies (P= 0.001, P= 0.002 and P= 0.02, respectively). There was also a strong positive correlation between S. pneu positivity with asthma attacks and bronchitis (P= 0.02 and P= 0.001, respectively). Moreover, a positive correlation was found between EV infection and atopic dermatitis (P=0.001). Furthermore, a positive correlation was found between AV infection and RSVA, B with allergic rhinitis (P= 0.02 and P= 0.001, respectively).

The frequency of the studied infections according to gender is presented in Table 2. In the girl group, only 6 cases (50%) had contamination with HIB, S. aur and S. pneu, while, in the boy group, 11 (37.9%) were infected with HIB, 12 (41.4%) with S. aur and 10 (34.5%) with S. pneu. In boys, 3/29 (10.3%) were infected with HRSV- A, B, while this infection was not observed in the girl group.

|

|

Male (boy) |

Female (girl) |

||

|

Positive outcomes |

Positive outcomes |

|||

|

Frequency |

percent |

Frequency

|

Percent |

|

|

HIB |

11 |

37.9 |

6 |

50 |

|

S.aur |

12 |

41.4 |

6 |

50 |

|

S.pneu |

10 |

34.5 |

6 |

50 |

|

Cpneu |

7 |

24.1 |

5 |

41.7 |

|

AV |

3 |

10.3 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

HRSV-A,B |

3 |

10.3 |

0 |

0 |

|

HCoV-HKU |

2 |

6.9 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

EV |

1 |

3.4 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

HBoV |

1 |

3.4 |

0 |

0 |

|

HCoV-43 |

1 |

3.4 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

FluB |

1 |

3.4 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

H1N1 |

1 |

3.4 |

0 |

0 |

|

PV |

1 |

3.4 |

1 |

8.3 |

|

M.pneu |

1 |

3.4 |

0 |

0 |

Clinical findings

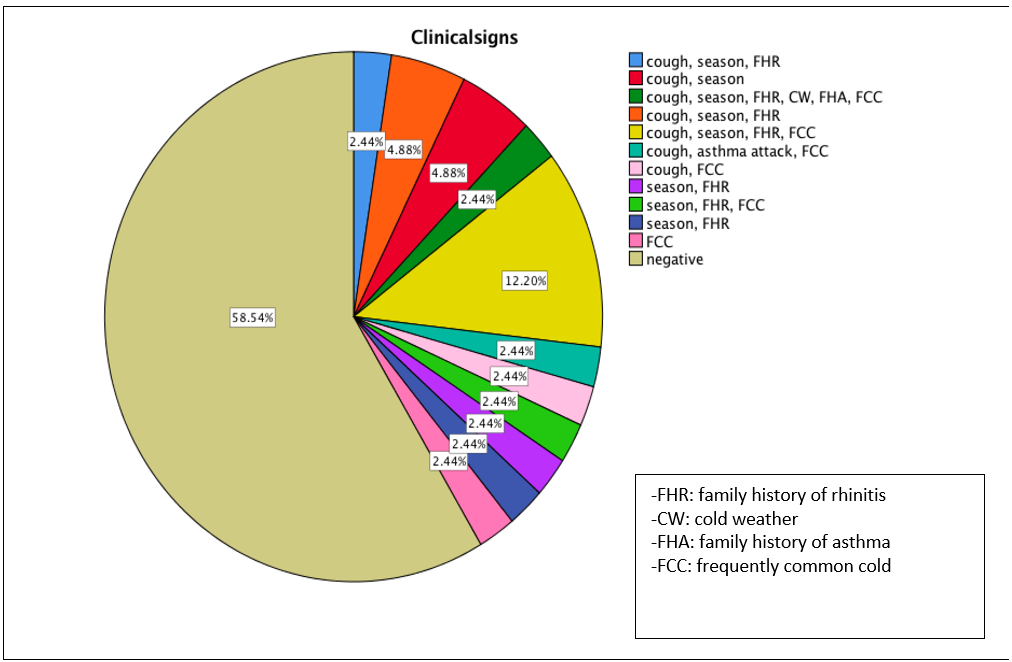

Fifty-nine percent of children suffered from chronic cough, while the start age of coughing in the affiliated children was 2-4-year-old (70.6%) (Table 3). Other risk factors, including cold weather, the season of symptom crisis and family history, were observed in 5.9%, 76.5% and 23% of children, respectively. Rhinitis, pneumonia and asthma attacks were also observed in 94.1%, 5.9% and 5.8%, respectively. Almost 59% of the children experienced the common cold frequently in winter.

|

Respiratory Pathogens |

1 to 5 years |

6 to 10 years |

11 to 16 years |

|||

|

Positive outcomes |

Positive outcomes |

Positive outcomes |

||||

|

Frequency |

percent |

Frequency

|

percent |

Frequency

|

Percent |

|

|

FluB |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4.3 |

1 |

33.3 |

|

H1N1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4.3 |

0 |

0 |

|

HIB |

4 |

26.7 |

12 |

52.2 |

1 |

33.3 |

|

HRSV-A,B |

0 |

0 |

3 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

PV |

1 |

6.7 |

1 |

4.3 |

0 |

0 |

|

EV |

0 |

0 |

2 |

8.7 |

0 |

0 |

|

AV |

1 |

6.7 |

3 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

HBoV |

1 |

6.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

HPIV-1 |

1 |

6.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

HCoV-43 |

1 |

6.7 |

1 |

4.3 |

0 |

0 |

|

HCoV-HKU |

1 |

6.7 |

2 |

8.7 |

0 |

0 |

|

S.aur |

7 |

46.7 |

11 |

47.8 |

0 |

0 |

|

S.pneu |

6 |

40 |

9 |

39.1 |

1 |

33.3 |

|

C.pneu |

4 |

26.7 |

8 |

34.8 |

0 |

0 |

|

M.pneu |

1 |

6.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Results from the Chi-Square test showed a close relationship between the microbial infections and the clinical symptoms (P=0.003). Which viruses including H1B, S. aur, S. pneu and C. pneu, were the most studied agents in clinical symptom exacerbations. Also, the results of the Kruskal-Wallis test showed a meaningful relationship between the clinical signs and HCoV-43 (P=0.0001).

Discussion

In this study, respiratory pathogens were assessed in asthmatic children 2-16 years old in the pilgrimage and touristic region of the Khorasan Razavi province, northeast Iran. The results of the present study on the agents that exacerbate asthma attacks were generally consistent with those observed by several authors worldwide, but sometimes they were different microbial pathogens [21,22]. The key findings of this study were 1) H1B followed by HRSV-A, B, PV, EV, HCoV-43, HCoV-HKU, and Flu-B are the most frequent pathogens in children associated with asthma symptoms; 2) male children were more susceptible to the respiratory infections than the females and 3) compared to the adults, the infants and children were more vulnerable to the respiratory viruses [7,23-25].

The results of the current study showed that exposure to viruses in childhood with asthma could increase airway obstruction, inflammation and lung dysfunctions, causing asthma exacerbation. The data clarify the vital function of viral respiratory infections in asthma exacerbations and confirm the close connection between viral infection and asthma deterioration. Viral infections are generally recognized as the main players in progressing to acute asthma exacerbations (50–85%) [26-28]. However, prospective monitoring of nasopharyngeal samples during the peak season for viral infections and asthma exacerbations provides evidence of a close relationship between viral, bacterial, and respiratory symptoms. However, it has been shown that allergen exposure, gender, age, environmental and inherited factors are associated with asthma exacerbation. Previous studies proposed the high rate of viral respiratory infections and their inflammatory responses as the significant cause of morbidity and mortality in asthmatic patients [29-31]. Our data is consistent with prospective studies demonstrating that asthma exacerbations coincide with the prevalence of respiratory viruses, particularly in autumn and winter [32,33]. In individuals who were monitored regularly, respiratory viruses are discovered in ~ 40% of asthma worsening [10,34,35].

According to the literature, specific infections such as H1N1, EV, and AV are closely connected with asthma attacks, bronchitis, food allergy, atopic dermatitis and rhinitis, respectively [36]. Our findings showed that it is more likely that after colonization of the viral respiratory infections, S. pneu can worsen asthma attacks because of the immune system's weakness.

A positive correlation between RSV-A B with allergy and rhinitis symptoms was also noted. Former clinical surveys approved the role of RSV and, to some extent, that of HMPV in the induction of asthma in the respiratory tract. Our collected data aligns with other surveys showing that RSV and picornaviruses infections were mainly associated with acute expiratory wheezing in hospitalized infants [17,37-39]. Asthmatic infant girls who are immunocompromised are more at risk of severe viral infections of viruses such as coronaviruses [40,41]. Regarding influenza viruses, studies have shown that influenza is safe for asthmatic patients [42]. The low rate of Flu-B and a negative case of Flu-A in the current study are consistent with the results that showed Flu viruses caused respiratory diseases in young and middle-aged individuals than adolescents [43]. Some studies have shown that the spread of Flu with S. pneu causes pneumonia, bronchitis, sinus infections and ear infections [44,45]. However, in the present study, although S. pneu was frequent in asthmatic children and was associated with the exacerbation of asthma attacks, there were no Flu infections in our population.

Similar to previous studies, a low rate of HPIV in asthmatic children was observed. However, the incidence of H1N1 infection was significantly higher in asthmatic children than in non-asthmatic children [46,47]. This result is inconsistent with our results, which also cover autumn. The present study also showed that children seem to have a lower rate of respiratory viral infection than adults, but asthma attacks could occur in the presence of infection colonization. In addition, viral infections associated with the opportunistic bacterial flora seem to be symptomatic, and in children with asthma, they are more likely to be associated with asthma exacerbations. A recent pooled meta-analysis of 60 studies across all ages and continents found that the prevalence of respiratory viruses associated with asthma exacerbations was <15% [16]. However, the present study showed that around 39% of microbial asthma is viral. Notably, the low rates of positive viruses in asthmatic older children in our study could be explained by the fact that exposure to some bacterial or viral products has increased the maturity of innate and acquired immunity.

Our study indicated a predominant circulation of H1B bacteria in asthmatic individuals. This opportunistic bacterium was detected in 41.5% of the children with asthmatic exacerbations, which is consistent with some other studies on adulthood [48]. Although H1B, S. aur, S. pneu and C. pneu are more detected in infant and school-aged children, other infection agents are less common in adolescents [45].

Mixed etiology and different pathogenic roles of viruses and bacteria lead to respiratory secretions in combination or alone. The findings of our study are shown in Figures 1 and 2, and, surprisingly, mixed bacterial infections of S. aur, S. pneu and C. pneu have been more common in 15% of the infections, and in a single infection, the S. aur was predominant. S. aur alone or in the mixed bacterial infection has been the main cause of triggering asthma attacks in this region.

Figure 1. The frequency of mixed or single respiratory pathogens in symptomatic children.

Figure 2. The frequency of signs and symptoms in studied subjects.

S. aur develops the chronic rhinosinusitis via a TH2-biased immune response to staphylococcal enterotoxins (SE) through IgE-independent and IgE-dependent inflammatory reactions [49]. Nasal colonization with S. aur worsens eczema [49,50]. Aside from eczema, S. aur has been implicated in the development and severity of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and food allergy. Building on these findings, S. aur nasal colonization could be nominated as a risk factor for a range of asthma-associated outcomes, including diagnosis, symptoms, and exacerbations, among the population.

Furthermore, although HIB has been a more frequent bacterial infection in asthmatic children, it could only exacerbate asthma attacks around 5% and 41% as mixed with other bacterial or viral infections, respectively. The close association of bacteria and, to a lesser extent, opportunistic respiratory viruses is little known in asthmatic children. Although evaluating the overall contribution of each virus/bacteria to disease severity is complicated by the presence of many confounding factors in clinical studies, understanding the role of each virus/bacteria in defining the asthma outcome will potentially reveal novel treatment and prevention strategies and also improving patient outcomes [51,52].

The present study has some limitations; firstly, the size of samples could be more significant, and secondly, the main para-clinical analysis should be collected in the expected condition and after infection thirdly, it is possible in such populations to collect samples in different environmental conditions, such as exercise, diets, TV watching time, and using junk food.

Conclusions

In conclusion, while there is no doubt that age, race, genetic, gender, and environmental factors are involved in the onset of asthma respiratory symptoms, the results of the present study provide further evidence that these risk factors per se are insufficient to cause an exacerbation and highlight the importance of viruses and some common bacterial infections which may facilitate developing or progressing toward asthma attacks.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the children who participated in this study. This study was granted by the Vice-Chancellor for Biomedical Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS: 931307).

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

References

2. Health NIo. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO workshop report. 1995.

3. Fuchs O, von Mutius E. Prenatal and childhood infections: implications for the development and treatment of childhood asthma. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2013 Nov 1;1(9):743-54.

4. De Marco R, Locatelli F, Cazzoletti L, Bugianio M, Carosso A, Marinoni A. Incidence of asthma and mortality in a cohort of young adults: a 7-year prospective study. Respiratory Research. 2005 Dec;6(1):95.

5. Dharmage SC, Perret JL, Custovic A. Epidemiology of asthma in children and adults. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 18;7:246.

6. Miller MK, Lee JH, Miller DP, Wenzel SE, TENOR Study Group. Recent asthma exacerbations: a key predictor of future exacerbations. Respiratory Medicine. 2007 Mar 1;101(3):481-9.

7. Özcan C, Toyran M, Civelek E, Erkoçoğlu M, Altaş AB, Albayrak N, et al. Evaluation of respiratory viral pathogens in acute asthma exacerbations during childhood. Journal of Asthma. 2011 Nov 1;48(9):888-93.

8. GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 2017 Sep;5(9):691.

9. Ahanchian H, Jones CM, Chen YS, Sly PD. Respiratory viral infections in children with asthma: do they matter and can we prevent them?. BMC Pediatrics. 2012 Dec;12:147.

10. Busse WW, Lemanske RF, Gern JE. Role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. The Lancet. 2010 Sep 4;376(9743):826-34.

11. Carroll KN, Hartert TV. The impact of respiratory viral infection on wheezing illnesses and asthma exacerbations. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2008 Aug 1;28(3):539-61.

12. Ray A, Kolls JK. Neutrophilic inflammation in asthma and association with disease severity. Trends in Immunology. 2017 Dec 1;38(12):942-54.

13. Hall S, Agrawal DK. Key mediators in the immunopathogenesis of allergic asthma. International Immunopharmacology. 2014 Nov 1;23(1):316-29.

14. Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, Regamey N. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2011 Jan;24(1):210-29.

15. Jacobs SE, Lamson DM, St. George K, Walsh TJ. Human Rhinoviruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2013 Jan;26(1):135-62.

16. Zheng XY, Xu YJ, Guan WJ, Lin LF. Regional, age and respiratory-secretion-specific prevalence of respiratory viruses associated with asthma exacerbation: a literature review. Archives of Virology. 2018 Apr;163(4):845-53.

17. Calvo C, García-García ML, Blanco C, Pozo F, Flecha IC, Pérez-Breña P. Role of rhinovirus in hospitalized infants with respiratory tract infections in Spain. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2007 Oct 1;26(10):904-8.

18. Puranik S, Forno E, Bush A, Celedón JC. Predicting severe asthma exacerbations in children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2017 Apr 1;195(7):854-9.

19. Darveaux JI, Lemanske Jr RF. Infection-related asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2014 Nov 1;2(6):658-63.

20. Wisniewski JA, McLaughlin AP, Stenger PJ, Patrie J, Brown MA, El-Dahr JM, et al. A comparison of seasonal trends in asthma exacerbations among children from geographic regions with different climates. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 2016 Nov;37(6):475-81.

21. Bizzintino J, Lee WM, Laing IA, Vang F, Pappas T, Zhang G, et al. Association between human rhinovirus C and severity of acute asthma in children. European Respiratory Journal. 2011 May 1;37(5):1037-42.

22. Fujitsuka A, Tsukagoshi H, Arakawa M, Goto-Sugai K, Ryo A, Okayama Y, et al. A molecular epidemiological study of respiratory viruses detected in Japanese children with acute wheezing illness. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2011 Dec;11:162.

23. Wijga A, Tabak C, Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Wieringa MH, Hoekstra MO, et al. Sex differences in asthma during the first 8 years of life: the Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy (PIAMA) birth cohort study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011 Jan 1;127(1):275-7.

24. Rawlinson WD, Waliuzzaman Z, Carter IW, Belessis YC, Gilbert KM, Morton JR. Asthma exacerbations in children associated with rhinovirus but not human metapneumovirus infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003 Apr 15;187(8):1314-8.

25. Lee WM, Kiesner C, Pappas T, Lee I, Grindle K, Jartti T, et al. A diverse group of previously unrecognized human rhinoviruses are common causes of respiratory illnesses in infants. PloS One. 2007 Oct 3;2(10):e966.

26. Henderson FW, Clyde Jr WA, Collier AM, Denny FW, Senior RJ, Sheaffer CI, et al. The etiologic and epidemiologic spectrum of bronchiolitis in pediatric practice. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1979 Aug 1;95(2):35-9.

27. Minor TE, Dick EC, DeMeo AN, Ouellette JJ, Cohen M, Reed CE. Viruses as precipitants of asthmatic attacks in children. Jama. 1974 Jan 21;227(3):292-8.

28. McIntosh K, Ellis EF, Hoffman LS, Lybass TG, Eller JJ, Fulginiti VA. The association of viral and bacterial respiratory infections with exacerbations of wheezing in young asthmatic children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1973 Apr 1;82(4):578-90.

29. Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quirós ME, Lasky-Su J, Avila L, Ly NP, et al. Dust mite exposure modifies the effect of functional IL10 polymorphisms on allergy and asthma exacerbations. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008 Jul 1;122(1):93-8.

30. Han YY, Lee YL, Guo YL. Indoor environmental risk factors and seasonal variation of childhood asthma. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2009 Dec;20(8):748-56.

31. Jartti T, Gern JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017 Oct 1;140(4):895-906.

32. Johnston NW, Sears MR. Asthma exacerbations· 1: epidemiology. Thorax. 2006 Aug;61(8):722-8.

33. Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Gustafson P, McCrae C, Edsbäcker S, Johnston N. Seasonal and geographic variations in the incidence of asthma exacerbations in the United States. Journal of Asthma. 2017 Sep 14;54(8):818-24.

34. Seemungal T, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, Moric I, Sanderson G, Message S, et al. Respiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001 Nov 1;164(9):1618-23.

35. Johnston NW, Lambert K, Hussack P, de Verdier MG, Higenbottam T, Lewis J, et al. Detection of COPD exacerbations and compliance with patient-reported daily symptom diaries using a smartphone-based information system. Chest. 2013 Aug 1;144(2):507-14.

36. Yeh JJ, Lin CL, Hsu WH. Effect of enterovirus infections on asthma in young children: A national cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017 Dec;47(12):e12844.

37. Knudson C, Varga S. The relationship between respiratory syncytial virus and asthma. Veterinary Pathology. 2015;52(1):97-106.

38. Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Österback R, van den Hoogen B, Osterhaus AD, et al. Respiratory picornaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus as causative agents of acute expiratory wheezing in children. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004 Jun;10(6):1095.

39. Salimi V, Tavakoli-Yaraki M, Yavarian J, Bont L, Mokhtari-Azad T. Prevalence of human respiratory syncytial virus circulating in Iran. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2016 Mar 1;9(2):125-35.

40. Amini R, Jahanshiri F, Amini Y, Sekawi Z, Jalilian FA. Detection of human coronavirus strain HKU1 in a 2 years old girl with asthma exacerbation caused by acute pharyngitis. Virology Journal. 2012 Dec;9:142.

41. Fielding BC. Human coronavirus NL63: a clinically important virus?. Future Microbiology. 2011 Feb;6(2):153-9.

42. Schwarze J, Openshaw P, Jha A, Del Giacco SR, Firinu D, Tsilochristou O, et al. Influenza burden, prevention, and treatment in asthma-A scoping review by the EAACI Influenza in asthma task force. Allergy. 2018 Jun;73(6):1151-81.

43. Veerapandian R, Snyder JD, Samarasinghe AE. Influenza in asthmatics: for better or for worse?. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018 Aug 10;9:1843.

44. Control CfD, Prevention. People at high risk for flu complications. 2019.

45. Kumar S, Roy RD, Sethi GR, Saigal SR. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and asthma in children. Tropical Doctor. 2019 Apr;49(2):117-9.

46. Maykowski P, Smithgall M, Zachariah P, Oberhardt M, Vargas C, Reed C, et al. Seasonality and clinical impact of human parainfluenza viruses. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2018 Nov;12(6):706-16.

47. Kloepfer KM, Olenec JP, Lee WM, Liu G, Vrtis RF, Roberg KA, et al. Increased H1N1 infection rate in children with asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012 Jun 15;185(12):1275-9.

48. Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1993 Oct 10;307(6910):982-6.

49. Bachert C, Zhang N. Chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma: novel understanding of the role of IgE ‘above atopy’. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2012 Aug;272(2):133-43.

50. Davis MF, Peng RD, McCormack MC, Matsui EC. Staphylococcus aureus colonization is associated with wheeze and asthma among US children and young adults. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015 Mar 1;135(3):811-3.

51. Saglani S. Viral infections and the development of asthma in children. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease. 2013 Aug;1(4):139-50.

52. Martinez FD. Viral infections and the development of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 May 1;151(5):1644-7.