Abstract

CD133 is a transmembrane protein that mainly localizes to the plasma membrane of normal stem cells as well as cancer stem cells, and is widely known as a cancer stem cell marker. CD133 was recently shown to localize in the cytoplasm; however, its transport pathway and functions currently remain unknown. We herein revealed that in an extracellular environment that is unsuitable for cancer cell growth, CD133 was down-regulated in cells and transported in endosomes to centrosomes. We also demonstrated that centrosome-localized CD133 captured GABARAP, a molecule involved in the initiation of autophagy, and inhibited the GABARAP-mediated activation of ULK1 and subsequent initiation of autophagy. Furthermore, CD133 localized to centrosomes in order to inhibit cell differentiation, such as the formation of primary cilia and neurite outgrowth, by suppressing autophagy. These results demonstrate that centrosome-localized CD133 plays an important role in maintaining cancer cells in an undifferentiated state.

Keywords

Cancer stem cell, CD133, Autophagy, Centrosome, Endosome

Commentary

Cancer cells were previously considered to accumulate genetic mutations over time in a single population of cells, resulting in a more aggressive population. However, cancer stem cells were recently discovered in cancer cell populations, and have been suggested to possess properties that produce tumor cell heterogeneity and resistance to drugs and radiation [1]. Although cancer stem cells were shown to express specific cell surface markers, a functional analysis of these markers has been delayed due to the very low proportion of cancer stem cells in tumor cell populations [1].

CD133, also called prominin 1, was originally identified as a cell surface marker of human hematopoietic stem cells and mouse neuroepithelial cells [2-4]. It was subsequently reported to function as a marker of cancer stem cells in solid tumors, such as brain tumors [5], colon cancer [6,7], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [8], and neuroblastoma [9]. The CD133-positive cell population has a greater self-renewal ability and chemoresistance phenotype than the CD133-negative cell population. The expression of CD133 correlates with malignant characteristics and a poor prognosis in many tumors [10]. CD133 is phosphorylated at its intracellular C-terminal domain by Src family tyrosine kinases [11], and, as a result, activates the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI-3K) by binding. PI-3K, in turn, activates downstream targets, such as Akt, thereby promoting the proliferation of glioma stem cells [12]. CD133 is stabilized by binding with histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), and enhances the transcriptional activity of β-catenin, resulting in the acceleration of cell growth and suppression of cell differentiation [13].

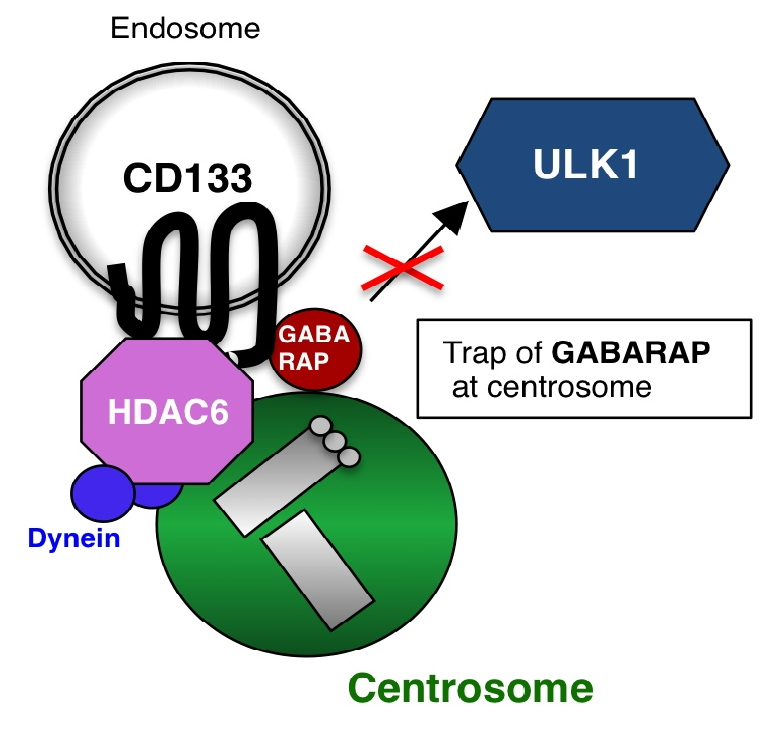

Here, to elucidate the new mechanisms contributing to the functions of CD133, we searched for cancer cell lines expressing high levels of CD133, and identified Huh-7, a cell line for hepatocellular carcinoma, and SK-N-DZ, a cell line for neuroblastoma. Immunofluorescent microscopy analyses showed that CD133 predominantly localized to centrosomes rather than the plasma membrane in Huh-7 and SK-N-DZ cells [14]. Further analyses revealed that when Src family kinase activity was low, CD133 was not phosphorylated by Src, and, as a result, unphosphorylated-CD133 was down-regulated in cells and preferentially interacted with HDAC6, whereby CD133 endosomes were transported to centrosomes by intracellular transport via the dynein motor [14] (Figure 1). Centrosomes are major microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) in animal cells and have key roles in regulating cell polarity and motility as well as spindle formation, chromosome segregation and cytokinesis [15]. More recently, centrosomes have also been reported to be involved in regulation of autophagy [16].

Figure 1: Schematic image of the centrosomal localization of endosomal CD133. Under conditions in which Src family kinase is inactivated, non-phosphorylated CD133 is transported from the plasma membrane to the intracellular region through endocytosis. After endocytosis, HDAC6 and dynein motors assist CD133 endosome trafficking along microtubules to centrosomes. Endosomal CD133, which localizes to centrosomes, captures GABARAP to inhibit the GABARAP-ULK1 interaction, thereby suppressing the initiation of autophagy.

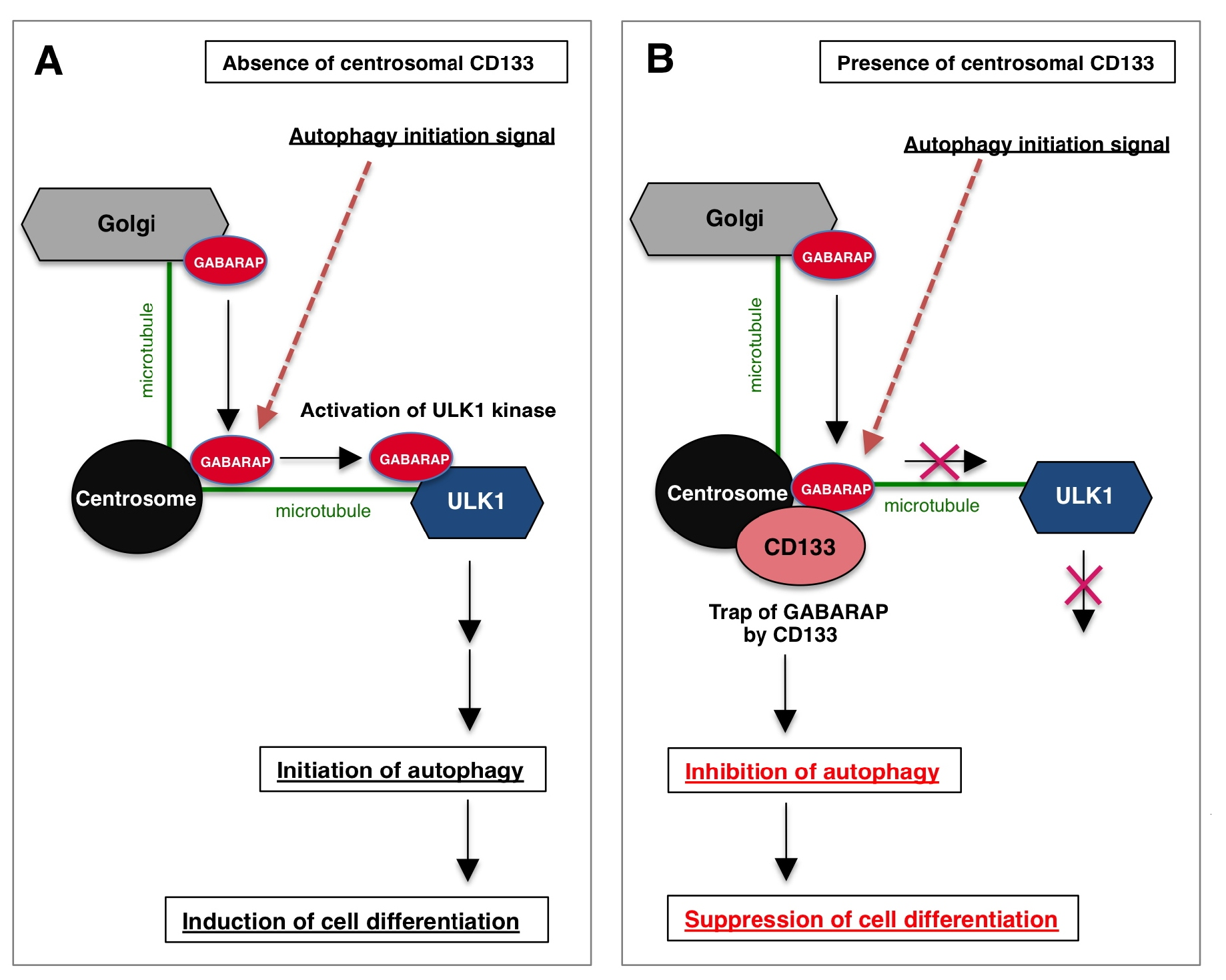

We then investigated the biological functions of centrosome-localized CD133. The findings obtained revealed that centrosome-localized CD133 captured GABARAP, a key regulator of autophagy initiation [16-18], and inhibited the GABARAP-mediated activation of ULK1 and subsequent initiation of autophagy [14] (Figure 2). The CD133 amino acid sequence (828-831 a.a. (Y-D-D-V)), including the phosphorylation site (Y828) by Src kinase, was also conserved as an LC3B-interacting region (LIR: Y/F-X-X-V), which has alternatively been recognized as a GABARAP-interacting motif [19]. Therefore, CD133 may capture GABARAP via this potential LIR.

We also examined the physiological functions of centrosome-localized CD133. Autophagic activity is necessary for cell differentiation in stem cells, such as neural stem cells and embryonic stem cells [20]. Our findings showed that centrosome-localized CD133 suppressed cell differentiation, such as the formation of primary cilia and neurite outgrowth, in neuroblastoma cells [14] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Schematic image of the centrosomal function of CD133 in cells. (A) In the absence of centrosomal CD133, when the autophagy initiation signal is activated, centrosome localized-GABARAP moves along microtubules and binds to ULK1, the top of the autophagy signal cascade, resulting in the activation of ULK1. Activated ULK1 then induces autophagy, and cell differentiation occurs. (B) In the presence of centrosomal CD133, when the autophagy initiation signal is activated, centrosome localized-GABARAP is captured by CD133, thereby inhibiting GABARAP-ULK1 complex formation. As a result, the autophagy initiation signal is inhibited and cell differentiation is suppressed. Thus, centrosomal CD133 has the unique property of maintaining the undifferentiated state of cells by inhibiting autophagy.

Thus, we demonstrated that centrosome-localized CD133 has a new important function: it plays an important role in maintaining cancer cells in an undifferentiated state by inhibiting autophagy. Based on our study, in the near future, the search for molecular compounds that directly induce cancer stem cell differentiation may open the door to novel therapies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Y. Kaneko and A. Nakagawara for their valuable discussions. We also thank our laboratory members for their continuous encouragement. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, Takeda Research Support, Japan and Gold Ribbon Network, Japan.

Author Contribution

H. I. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

2. Miraglia S, Godfrey W, Yin AH, Atkins K, Warnke R, Holden JT, et al. A novel five-transmembrane hematopoietic stem cell antigen: isolation, characterization, and molecular cloning. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 1997 Dec 15;90(12):5013-21.

3. Weigmann A, Corbeil D, Hellwig A, Huttner WB. Prominin, a novel microvilli-specific polytopic membrane protein of the apical surface of epithelial cells, is targeted to plasmalemmal protrusions of non-epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1997 Nov 11;94(23):12425-30.

4. Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, Almeida-Porada G, Ogawa M, Leary AG, et al. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 1997 Dec 15;90(12):5002-12.

5. Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Research. 2003 Sep 15;63(18):5821-8.

6. O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007 Jan;445(7123):106-10.

7. Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007 Jan;445(7123):111-5.

8. Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007 Jun 1;132(7):2542-56.

9. Takenobu H, Shimozato O, Nakamura T, Ochiai H, Yamaguchi Y, Ohira M, et al. CD133 suppresses neuroblastoma cell differentiation via signal pathway modification. Oncogene. 2011 Jan;30(1):97-105.

10. Li Z. CD133: a stem cell biomarker and beyond. Experimental hematology & oncology. 2013 Dec;2(1):17.

11. Boivin D, Labbé D, Fontaine N, Lamy S, Beaulieu É, Gingras D, et al. The stem cell marker CD133 (prominin-1) is phosphorylated on cytoplasmic tyrosine-828 and tyrosine-852 by Src and Fyn tyrosine kinases. Biochemistry. 2009 May 12;48(18):3998-4007.

12. Wei Y, Jiang Y, Zou F, Liu Y, Wang S, Xu N, et al. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by CD133-p85 interaction promotes tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013 Apr 23;110(17):6829-34.

13. Mak AB, Nixon AM, Kittanakom S, Stewart JM, Chen GI, Curak J, et al. Regulation of CD133 by HDAC6 promotes β-catenin signaling to suppress cancer cell differentiation. Cell reports. 2012 Oct 25;2(4):951-63.

14. Izumi H, Li Y, Shibaki M, Mori D, Yasunami M, Sato S, et al. Recycling endosomal CD133 functions as an inhibitor of autophagy at the pericentrosomal region. Scientific reports. 2019 Feb 19;9(1):1-8.

15. Nigg EA, Holland AJ. Once and only once: mechanisms of centriole duplication and their deregulation in disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2018 May;19(5):297.

16. Joachim J, Jefferies HB, Razi M, Frith D, Snijders AP, Chakravarty P, et al. Activation of ULK kinase and autophagy by GABARAP trafficking from the centrosome is regulated by WAC and GM130. Molecular cell. 2015 Dec 17;60(6):899-913.

17. Joachim J, Tooze SA. Centrosome to autophagosome signaling: Specific GABARAP regulation by centriolar satellites. Autophagy. 2017 Dec 2;13(12):2113-4.

18. Joachim J, Tooze SA. Control of GABARAP‐mediated autophagy by the Golgi complex, centrosome and centriolar satellites. Biology of the Cell. 2018 Jan;110(1):1-5.

19. Rogov V, Dötsch V, Johansen T, Kirkin V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Molecular cell. 2014 Jan 23;53(2):167-78.

20. Mizushima N, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian development and differentiation. Nature cell biology. 2010 Sep;12(9):823-30.